Public Housing Tenant Movement Fractures

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "All Housing is Public," Chapter Seven of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

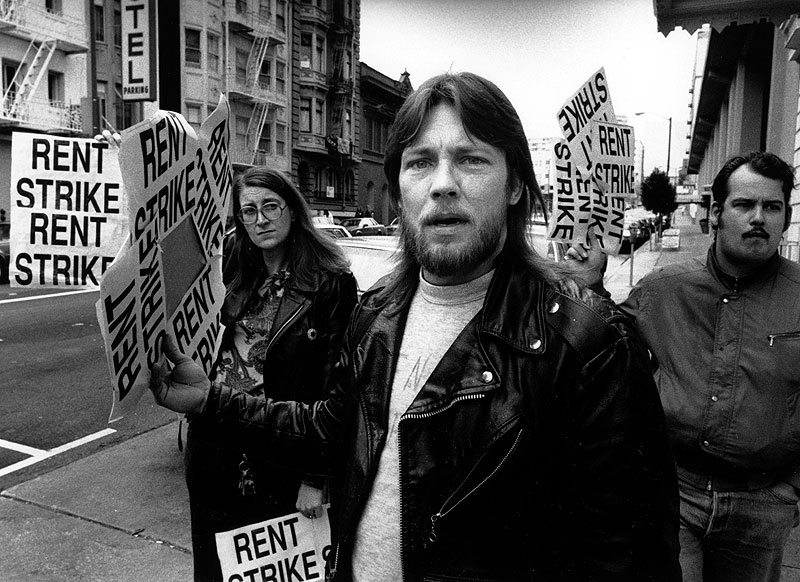

Rent strike in the Tenderloin, April 1989.

Photo: © Phil Head, for the Tenderloin Times, courtesy SF History Center, SF Public Library

The Alice Griffith Homes demolition and Rosa Parks conversion highlighted the difficult decisions facing the SFHA community in an era of federal cuts; they also signaled growing divisions among tenants. To be sure, tenants of all ages and family types still worked together on voter registration campaigns and on pressuring local and federal leaders to do more for public housing. And Public Housing Tenants Association (PHTA) representatives attended NTO and NAHRO conferences and nominated tenants to the SFHA commission.(80) Tenants still ran a citywide summer food program, which in 1984 operated at 19 SFHA projects, served 2,400 meals a day, and employed 29 SFHA tenants.(81) But the PHTA was losing its unified voice. In 1982, the Hunters View, Westbrook, and Alice Griffith Tenants Associations wrote the SFHA commission to express “their wish to withdraw their participation from PHTA” and asked (unsuccessfully) for their share of PHTA financial allocations. Throughout the decade, other tenant associations asked to leave the PHTA, and tenants voiced their concerns and critiques of the PHTA. PHTA accounting and accountability problems regularly led the SFHA to stop funding the tenant organization and delay PHTA–SFHA contract renewals. PHTA leadership turnover and question- able elections at the project and city level weakened the organization even more.(82) As Commissioner Harry Chuck said, “With the shifts in leadership come shifts in priorities and approaches. It seemed that every two to three months there was a new group of officers coming before the Commission.”(83)

In 1983, the Seniors City-Wide Council (SCWC) broke away from the PHTA, a move that would hurt the public housing tenant movement. Made up of seniors and tenants with disabilities, the SCWC had formed because of PHTA problems and because of the different social identities of SCWC members. SCWC representatives attended SFHA meetings, worked on housing legislation, and served on SFHA committees.(84) The SCWC ran its own voter campaigns and remained active at the local and state level because “[a]ll of the senior residents of the San Francisco Housing Authority realize how important it is to be aware of what is happening politically and how it will affect them.”(85)

The SCWC tried to leave the PHTA legally and requested a prorated share of PHTA monies (roughly $5,000 per year). The SFHA Commission rejected both proposals.86 Throughout the 1980s, the SCWC leadership made it clear that the PHTA did not speak for them. In a 1988 letter to SFHA Director James Clay, SCWC President Mary Lou McAllister stated that her group wanted no part of the PHTA, however new and reorganized it might be that month. She noted that each senior building had its own association, which was part of a citywide “umbrella association.” McAllister said that there was “100% representation of individual senior tenant associations” at the citywide meetings, a model that represented “seniors in all matters of collective interest to the Authority staff and Commission. Our senior representative on the Housing Authority Commission serves as an appropriate advocate and liaison.” She wanted to “continue our current manner of representation” and emphasized that the “PHTA does not now, nor at any time whatsoever, speak for the disabled and senior tenants residing in the Authority’s senior housing units.”(87)

The PHTA’s internal problems strained its relationship with the SFHA. The PHTA leadership had always exercised a degree of autonomy over its affairs and its decisions regarding how to relate to the SFHA—as an adversary, a partner, or an ally. PHTA leaders often reminded the SFHA that “the internal affairs of the PHTA are to be resolved by PHTA and not Authority staff or the Commission.”(88) Yet the SFHA supplied staff and resources to the PHTA, including mediators for PHTA internal disputes, funds covering PHTA and senior tenants’ travel to NTO and NAHRO conferences, SFHA buses to move tenants around the city for events, and childcare to facilitate tenant participation.

Perhaps the most striking form of support came in 1988 when SFHA commissioners attended a PHTA meeting with the goal to “get PHTA reorganized and on its feet with a set of working by-laws, set of working officers and members committed to providing services to the tenants.” Commissioners pledged to assign an SFHA staff person to “help assess what is required in reorganizing the tenant associations and the PHTA” and to “look for outside sources of funding” to pay for an organizer to “work with the tenants to get the organization back on its feet.”(89) SFHA staff worked with property managers and tenants to rebuild “strong property organizations” to restore “a strong city wide organization,” but the PHTA never recovered the organizational strength it had had in the 1970s.(90)

The decline of the tenant movement can be understood in several ways. Section 8 housing spread tenants across the city’s low-income neighborhoods, and this made organizing and including them in the tenant movement more difficult. As the physical quality of SFHA units declined, many tenants lost faith in the SFHA program and their ability to improve their housing and neighborhoods. Some tenant associations prioritized their own project’s interests over citywide tenant interests. Incorporated tenant associations, a product of HUD policies, pursued grants for their own projects, creating a political landscape in which one tenant association sometimes competed with another for limited funding. When Ping Yuen tenants won a grant for their project, for example, SFHA Commissioner Elouise Westbrook said that she “did not like to see tenants competing against tenants.”(91)

Sometimes local elites encouraged individualistic tenant behavior by promoting neoliberal HUD policies. In 1991, following HUD Secretary Jack Kemp’s direction, San Francisco mayoral candidate Frank Jordan (Dem.) penned an open letter to the city’s public housing tenants. In it, Jordan blasted the SFHA and pitched the federal Homeownership and Opportunity for People Everywhere (HOPE) program as something “working all across the country.” Jordan wrote that HOPE “provides Resident Management Training” so that tenants would have “the skills necessary to eventually manage your own developments” and the “opportunity to own your developments for no more of your incomes than you’re currently paying for rent.” Jordan’s final point drove home the neoliberal message of individualism, choice, and private home ownership—as it offered a dig at his political opponent and current San Francisco Mayor Art Agnos. “Art Agnos opposes H.O.P.E because it takes the power to control your lives away from him and gives it back to you,” Jordan wrote, and “I believe you have the talent and energy to make H.O.P.E work. All you need is the chance to do it.”(92)

Food Not Bombs serving free meals in the Civic Center. Their steady presence eroded support for Mayor Art Agnos due to his inability to solve the increasingly visible population of homeless in the center of the city.

Photo: © Lance Woodruff for the Tenderloin Times, courtesy San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Eight months after Jordan became mayor, tenants at the Alemany project signed an agreement with the SFHA to manage their building and explore private ownership. The Bernal Heights project was the first in the city to be run by tenants, who now had to solve many of the structural problems of an underfunded program on their own rather than collectively across the city.(93) Tenants at Hunters View, Sunnydale, Holly Courts, and Robert B. Pitts projects soon followed their counterparts at Bernal Heights.(94)

previous article • continue reading

Notes

80. SFHA, Minutes, (November 10 and November 23, 1983; and October 23, 1986); Update (July 1984).

81. SFHA, Minutes (June 14, 1984); Update (July 1984).

82. Quote in SFHA, Minutes (October 14, 1982). For PHTA problems, see SFHA Minutes in the 1980s. In 1983, the SFHA took over the bill-paying duties for the PHTA. SFHA, Minutes (February 10, 1983). For a sample PHTA–SFHA contract, which had many of the same provisions as a labor union contract, see SFHA, Minutes (October 13, 1983).

83. SFHA, Minutes (October 22, 1987).

84. SFHA, Minutes (March 10, 1983).

85. Quote in Update (July 1982). Update and the SFHA Minutes document senior tenant activities.

86. SFHA, Minutes (October 28, 1982).

87. Quotes in SFHA, Minutes (March 24, 1988).

88. SFHA, Minutes (January 26, 1984).

89. SFHA, Minutes (February 25, 1988).

90. SFHA, Minutes (April 28, 1988).

91. SFHA, Minutes (February 28, 1985).

92. Robert De Monte to Frank Jordan, letter (December 19, 1991), Folder “1992 Corres,” Box 1, Program Subject Files, R. J. De Monte, Regional Administrator, 1988–1992, NARA/ SB, RG 207. A Feinstein appointee, SFHA Commissioner Preston Cook pushed for private sector and tenant management in 1980. See SFHA, Minutes (September 25, 1980).

93. The Alemany Resident Management Council took over SFHA services too, including childcare, employment training and counseling, literacy training, landscaping, co-op store, laundry, and recreation center. See Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Alemany RMC and SFHA in SFHA, Minutes (August 27, 1992).

94. SFHA, Minutes (August 8, 1991).

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.