Homelessness Surges in Wake of Neoliberalism

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "All Housing is Public," Chapter Seven of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

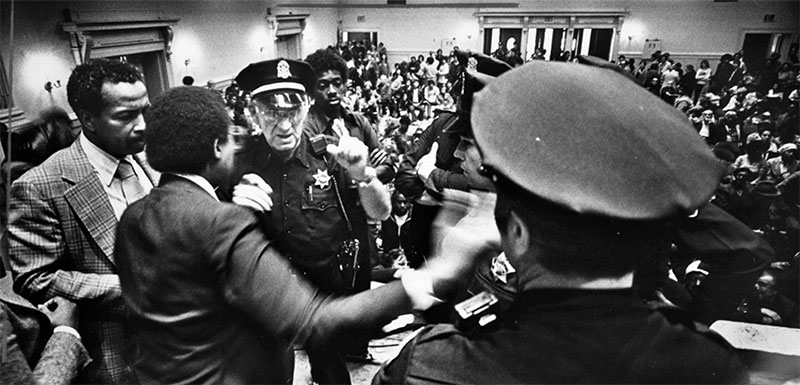

Overflow crowds at the San Francisco Housing Authority office in 1981 on the day designated for accepting applications. More than 5,000 applicants applied to join the SFHA's waiting list.

Photo: San Francisco Examiner image, courtesy Bancroft Library

The surge in the city’s homeless population became part of a national trend. No longer limited to mostly young and middle-aged male substance abusers, the mentally ill, or hobos living off the grid, the city’s homeless population now included workers, veterans, and families.(61) By 1982, San Francisco’s city leaders were holding regular conferences on the topic. Fresh from one of these conferences, SFHA Director Carl Williams provided a report, which he concluded by writing that the homeless problem “seems to be quite serious and growing.”(62) SFHA Commissioner Elouise Westbrook stated that the agency needed to do more “for the families in San Francisco who are homeless or living in deplorable conditions.”(63) During the 1980s, HUD, which had precipitated some of the problem in the first place by shrinking its affordable housing expenditures, responded by opening up Section 8 certificates to homeless applicants, and in 1985, the SFHA began applying for the newly created certificates.(64)

The growing homeless population in the nation prompted federal investigations and legislation. Congressional findings on homelessness found that the nation faced “an immediate and unprecedented crisis due to the lack of shelter for a growing number of individuals and families.” “Due to the record increase in homelessness,” the report added, “states, units of local government, and private voluntary organizations have been unable to meet the basic human needs of all the homeless.” The findings also highlighted the complexity of the problem, since the causes of homelessness and the needs of the homeless did not fit into neat categories. In 1987, the U.S. Congress passed the McKinney–Vento Homeless Assistance Act to expand and coordinate federal programs to better assist the nation’s homeless, including the growing number of homeless children. One of the key features of the McKinney–Vento legislation was that it channeled HUD funding through housing authorities, then to private and nonprofit entities that served the homeless.(65)

In San Francisco, Catholic Charities used this HUD funding to rehabilitate thirty-three SRO units and win an annual $190,000 contract for providing housing services. Catholic Charities received other McKinney funds to run the first hotel for AIDS patients in the nation. Other nonprofit housing providers in San Francisco focused on homeless veterans and substance abusers. Taken together, however, these housing solutions still did not have enough rooms and services to meet the needs of the homeless in San Francisco; there, as around the nation, backstreets, parks, and doorways swelled with people without homes.66 The SFHA featured prominently in discussions of homelessness, though the agency’s capacity to respond to the need was limited by changing tenant demographics and demand. In the 1970s and 1980s, U.S.-backed wars in Southeast Asia and Central America led to a surge in immigrants from these regions, and some settled in San Francisco. Many became SFHA tenants (the agency had dropped its citizenship requirement). By 1990, roughly 46 percent of the SFHA tenant population was African American, 30 percent Asian, 17 percent white, 1 percent Native American, and 6 percent Latina/o. The waiting list for SFHA housing numbered in the thousands, and in the rare instances when the SFHA accepted new applications, it attracted thousands of applicants who hoped to be added to the list. In these often chaotic scenes, elderly applicants slightly outnumbered family applicants.(67)

Of the 20,000 public housing tenants, 85 percent of SFHA tenant households received some kind of government social insurance program: Aid to Families with Dependent Children, disability insurance, or Social Security. Even though HUD raised the rent of subsidized housing to 30 percent of a tenant’s household gross income, the SFHA did not benefit from the higher rent collections because inflation ate up much of that added rental income. The SFHA added new staff and services for seniors, non-English speakers, and tenants with disabilities, none of whose costs were part of the 1937 Housing Act’s budget formula.(68)

Inflation and these new services, combined with repair costs, strained the SFHA program. From 1982 to 1992, the SFHA budget climbed from just over $20 million to $35 million, but when adjusted for inflation, that amount actually represented a decline of $16 million in purchasing power. To help offset this loss, the city waived the SFHA’s payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs). By 1992, the SFHA managed roughly 5,400 Section 8 units and about 6,500 permanent units, down from about 7,000 permanent units in 1982. With these two kinds of housing, the agency administered just over 2 percent of the city’s rentals.(69)

In this era, the losses in permanent housing units resulted from demolition of family housing in need of repairs. In 1982, the SFHA, with community support, bulldozed ninety-six apartments at the Alice Griffith Homes because, even though everyone agreed that it was unfortunate, the SFHA could no longer wait for HUD funding for needed repairs. The demolition of a project with such an important namesake was a grim example of the consequences of declining federal support and the declining capacity of the SFHA. Vandalism was also to blame for some of the physical decline and subsequent destruction of SFHA housing. Doors, fixtures, lights, wiring, and other materials disappeared or were broken. Pipes and valves necessary for boilers went missing, as did hot water for tenants. Tenants complained of month-long waits to get basic repairs from a decimated SFHA maintenance department whose overworked staff approached work orders like doctors in triage. Not all housing units were falling apart, but there were enough in bad shape to provide evidence of a program in need of assistance.(70) In many ways, this whole situation was predictable. It was the culmination of four decades of structural underfunding to ensure that public housing would not be more attractive than private housing. The situation also provided concrete examples for the neoliberal narrative of ineffective government.(71)

previous article • continue reading

Notes

61. Hays, The Federal Government and Urban Housing, chapter 8. See also Bratt, Hartman, and Meyerson, Critical Perspectives on Housing; Kay Young McChesney, “Family Homelessness: A Systemic Problem,” Journal of Social Issues 46, 4 (1990): 191–205; John M. Quigley, Steven Raphael, and Eugene Smolensky, “Homeless in America, Homeless in California,” Review of Economics and Statistics 83, 1 (February 2001): 37–51; Teresa Gowan, Hobos, Hustlers, and Backsliders: Homeless in San Francisco (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010).

62. SFHA, Minutes (November 24, 1982).

63. SFHA, Minutes (December 27, 1984).

64. SFHA, Minutes (April 25, 1985). For national homeless trends, see Martha R. Burt, Over the Edge: The Growth of Homelessness in the 1980s (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1993); Quigley, Raphael, and Smolensky, “Homeless in America, Homeless in California.”

65. SFHA, Minutes (April 25, 1985; December 10, 1987; and February 11, 1988). For congressional findings and language of the act, go here.

66. SFHA, Minutes (April 25, 1985; December 10, 1987; and February 11, 1988). Gowan, Hobos, Hustlers, and Backsliders.

67. Data from SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing,” and Carl Williams, “Public Housing Discussion Paper for the Mayor’s Housing Policy Group” (April 23, 1981). Both documents are in SFHA, Minutes (June 24, 1982). See SFHA, Minutes (August 26, 1982; and April 25, 1985). For 1990s data, see Memo to City Services Committee (May 22, 1990), “Operations of the SFHA, Board of Supervisors Budget Analysis” (1990) and Report to the Board of Supervisors “Management Audit of the SF Housing Authority” (November 1993).

68. Ibid.

69. Available SFHA housing stock changed daily as units and buildings came on or off line. From 1982–1992, the SFHA added 137 senior/disability units while demolishing 705 family units. Data from SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing,” and Williams, “Public Housing Discussion Paper for the Mayor’s Housing Policy Group,” both in SFHA, Minutes (June 24, 1982). And SFHA, Minutes (August 26, 1982; and April 25, 1985). For 1990s data, see Memo to City Services Committee and “Management Audit of the SF Housing Authority.”

70. Ibid.; for Alice Griffith Homes, see SFHA, Minutes (May 13 and July 22, 1982). For comparison, see Atlanta Housing Authority, “HOPE: Atlanta Housing Authority 15 Year Progress Report, 1995–2010.”

71. Rachel G. Bratt, “Public Housing: The Controversy and Contribution” in Bratt, Hartman, and Meyerson, Critical Perspectives on Housing, 335–61. Also see D. Bradford Hunt, Blueprint for Disaster: The Unraveling of Chicago Public Housing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Vale, Purging the Poorest; Howard, More Than Shelter; Bloom, Umbach, and Vale, Public Housing Myths.

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.