SF Housing Authority Copes With Neoliberalism

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "All Housing is Public," Chapter Seven of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

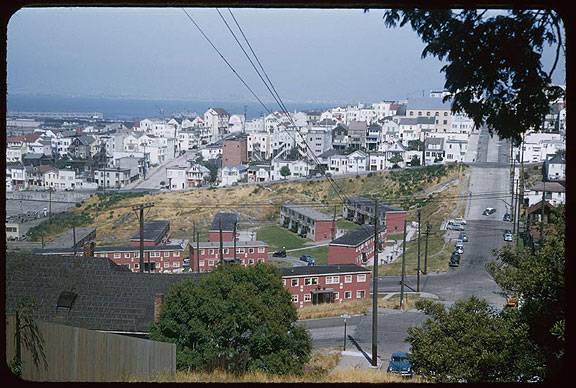

May 17, 1954, view of Public Housing projects at 19th and DeHaro. Later to be cleared for public school, and slopes behind have been filled with condominiums, after a lengthy public effort to maintain the open space.

Charles Cushman Collection: Indiana University Archives (P07134)

These apartments called Victorian Mews were built just uphill from the former site of the public housing project in the 1980s.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2009

In September 1981, the SFHA leadership formed a task force to explore the agency’s shrinking options. The group included PHTA president Cleo Wallace and tenant representative Francis Hugunin, Naomi Gray and Donald Tishman from the business sector, SFHA commissioners Joan Byrnes San Jule and Harry Chuck, William Witte from the San Francisco Office of Community Development, SFHA staffer Evert Heynneman, and SFHA Director Carl L. Williams. Their charge was to look at “how to provide the best ‘quality of life’ for the residents of public housing in the City despite the drastic budget cuts that are being proposed by the federal government.” Their work led to the 1982 publication of “Crisis in Public Housing: A Review of Alternatives for Public Housing in San Francisco and Recommendations for the Future.” In the area of property management, the report discussed the pros and cons of using private companies to manage public housing. These companies typically replaced a union and government workforce with a cheaper one and received federal subsidies, but, according to the report, these companies had at best a mixed managerial record.(53)

The report also looked at public housing tenant self-management, notably in St. Louis where a long rent strike had won public housing tenants their goal of self-management. Tenant management in St. Louis, as in other parts of the nation, involved extensive technical support from the local housing authority, HUD, consulting companies, and community organizations. Even with substantial support, tenants struggled with managing the daily affairs of their housing. Like housing authorities, tenants too were faced with the consequences of structural problems (higher rates of unemployment, crime, public and private institutional neglect, and so on) in their neighborhoods and the budget realities of running housing programs. The task force report recommended against the tenant self- management option—but it did recommend soliciting proposals from real estate management firms.(54)

The SFHA report discussed other alternatives that were in line with the Reagan administration’s housing goals. The “condomania” sweeping urban areas prompted the task force to investigate converting public housing into condominiums, but their report recommended against this option because the cost of such units would be “far above the ability for SFHA residents to pay.” The report also discussed converting public housing into cooperatives. When successful, cooperatives allowed individuals to build equity through home ownership, offered a high level of housing democracy, and generally produced a degree of resident stability and security. Although cheaper than condominiums (due to better financing), cooperatives, according to the task force, also proved too expensive.(55)

One last option in the report was for the SFHA to sell properties in order to generate revenue “to ensure the survival of other public housing developments.” The Reagan administration had “made it very clear” that it would eliminate the “plethora of regulatory and legal requirements” in the way of selling off public housing assets. The task force report noted that unsolicited proposals from real estate companies already showed “active interest” in SFHA properties. The possible sale of public housing, however, generated concerns for the task force members who wrote that the “emotional trauma involved in displacing a substantial number of public housing residents far outweighs the advantages of any income” from sales. Additionally, the loss of control over this housing by selling it to the private sector “would seriously exacerbate the [dearth of] housing opportunities for low-income persons.”(56)

Public housing and tenant activists protest at City Hall against efforts to sell off SFHA properties, 2021.

Photo: United Front Against Displacement

SFHA tenants also opposed the sale of public housing. North Beach tenant Mun Yee Leung was among many who stressed that tenants “are opposed to any sale.” The San Francisco Board of Supervisors followed suit with a resolution calling for “no change in the ownership or management of the San Francisco housing projects.” The task force report’s final recommendation veered from the national trajectory of neoliberal actions, stating that the SFHA should sell off its units only “as a measure of last resort.”(57) Too many residents depended on and wanted SFHA housing.

The task force’s reluctance to embrace privatization came, in part, from the intensification of the affordable housing crisis. Overall, the city’s population had declined in the 1970s, but began rising again in the 1980s (see Table A.1 in appendix). Housing costs had double-digit increases nationally, but in western cities such as San Francisco, rents and housing prices far outpaced national figures and wages adjusted for inflation. The number of single-room occupancy hotels (SROs)—long havens for San Francisco’s elderly, immigrants, and poor—dropped from 57,000 to 19,000 between 1975 and 1986, as investors converted SROs into condominiums, office space, and tourist hotels.58 The demolition of housing for redevelopment projects also decreased the number of affordable housing units. These losses, which included SROs, meant fewer choices, and a lower standard of living, for low-income households. Nonwhite families struggled the most in the housing market. As SFHA Commissioner A. E. Ubalde noted, “Landlords will not take families with children. If you have children and you’re black—that’s another strike against you.”(59) Director Carl Williams explained, “We should not fool ourselves in assuming that it is something that can be done by the private sector they have all indicated that they could not produce these units within the rent paying ranges of the persons who would be eligible for these units.”(60) The cumulative effects of these trends drove many low-income households, especially African Americans, out of the city or onto the streets.

previous article • continue reading

Notes

53. SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing: A Review of Alternatives for Public Housing in San Francisco and Recommendations for the Future” (1982). Contracting services out, or what became known as “reinventing government,” expanded rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s. Municipal governments alone tripled their service contract values with the private sector from $22 billion in 1972 to $66 billion in 1980. See Stephen Moore, “Contracting Out: A Painless Alternative to the Budget Cutter’s Knife,” Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science 36, 3 (1987): 60–73. Also see Daphne T. Greenwood, “The Decision to Contract Out: Understanding the Full Economic and Social Impacts” (Colorado Springs: Colorado Center for Policy Studies, March 2014); Arena, Driven from New Orleans.

54. SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing.” For tenant management, see Robert Kolodny, “What Happens When Tenants Manage Their Own Public Housing,” (Washington, DC: Office of Policy Development and Research, HUD, August 1983).

55. Quotes in SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing.”

56. Quotes in SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing.”

57. SFHA Public Housing Task Force, “Crisis in Public Housing.” For developer interests in SFHA properties, see report and SFHA, Minutes (April 8, 1982). Leung quote in SFHA, Minutes (April 8, 1982).

58. Godfrey, “Urban Development and Redevelopment in San Francisco”; Randy Shaw, “Tenant Power in San Francisco,” in James Brook, Chris Carlsson, and Nancy J. Peters, eds., Reclaiming San Francisco: History, Politics, and Culture (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1998). In 1978, housing costs rose 12 to 14 percent around the nation—17 percent on the West Coast. SFHA, Minutes (March 22, 1979). Sharon M. Keigher, Housing Risks and Homelessness Among the Urban Elderly (New York: Haworth Press, 1991), 78–87.

59. Quote in SFHA, Minutes (September 12, 1977).

60. SFHA, Minutes (September 11, 1980).

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.