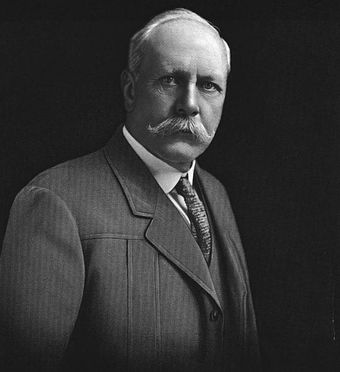

Captain John D. Spreckels

Historical Essay

by Felix Reisenberg, Jr.

John D. Spreckels, early 20th century.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Men to dominate sea-borne commerce at San Francisco, in the manner of railroad, bonanza, wheat, and sugar kings, did not emerge until the eighties, when there came the first of three maritime magnates whose fortunes were such that they followed in strong procession down to 1932, the year venerable Captain Robert Dollar slipped his cable. John D. Spreckels, son of San Francisco's "Sugar King," was first, followed closely by Captain William Matson. That there were any prominent shipowners, and that the last two were among the world's greatest, is remarkable. In the half-century following 1860 foreign trade increased three-fold, but the amount of it carried in American bottoms slipped from more than sixty-five to less than nine per cent.

Each of those shipping princes who looked westward through the Golden Gate envisioned for himself a place in the trade of the vast Pacific Ocean. The Pacific had always been a pathway of ships laden with wealth. After the galleons and English corsairs, American ships earned fabulous profits from pelts; tea clippers East Indiamen and independent trading vessels made fortunes for lucky owners. With the discovery of gold, treasure ships crossed its waters between San Francisco and the Isthmus. Perry made his treaty with Japan; Chinese coolies came to California; flour moved from the Golden Gate to China ports. Pacific Mail had barely opened the Orient when the Central Pacific Railroad moved in to run Occidental and Oriental liners in mock competition for forty years. But this monopoly was only one line drawn on a huge canvas: the Pacific was an ocean of endless opportunity.

Hawaii, mid-point of the Pacific, shorn of transshipment and whale supply business that marked its days as the Sandwich Islands, became the base for John D. Spreckels. The islands were then looming as a great sugar-production country, owing largely to the efforts of his father, Claus, the "Sugar King."

Born in Lamsted, Hanover, Claus had arrived in New York at the age of seventeen with a single thaler in his pocket. After working for one dollar a week as a grocery boy, he moved to North Carolina, where he owned his grocery when the gold rush started. Food prices were sky-high at San Francisco and Spreckels took passage with his family. So successful was the business that he established the Albany Brewery, whose profits enabled him to start the Bay Sugar Refining Company. Claus Spreckels then concentrated on sugar. Fascinated by the possibilities this commodity held, he traveled all over the world, to every known producing and refining area; he even entered a European beet factory as a worker. To him, sugar became a passion.

Fortified by his extensive investigation and growing capital, Spreckels invaded the Hawaiian Islands. King Kalakaua made him Knight Commander of the Order of Kalakaua; Claus made Hawaii one of the great producing centers of the world. As the business grew three sons were educated to carry on after him. John D. was chosen to go to Hawaii and he became the shipping man of the family.

The Spreckels Ships

An even-featured, good-looking lad with a blond mustache, John D. sailed for the islands with his bride. He was twenty-four, known as a practical joker and a good fellow, but withal as shrewd a trader as his father.

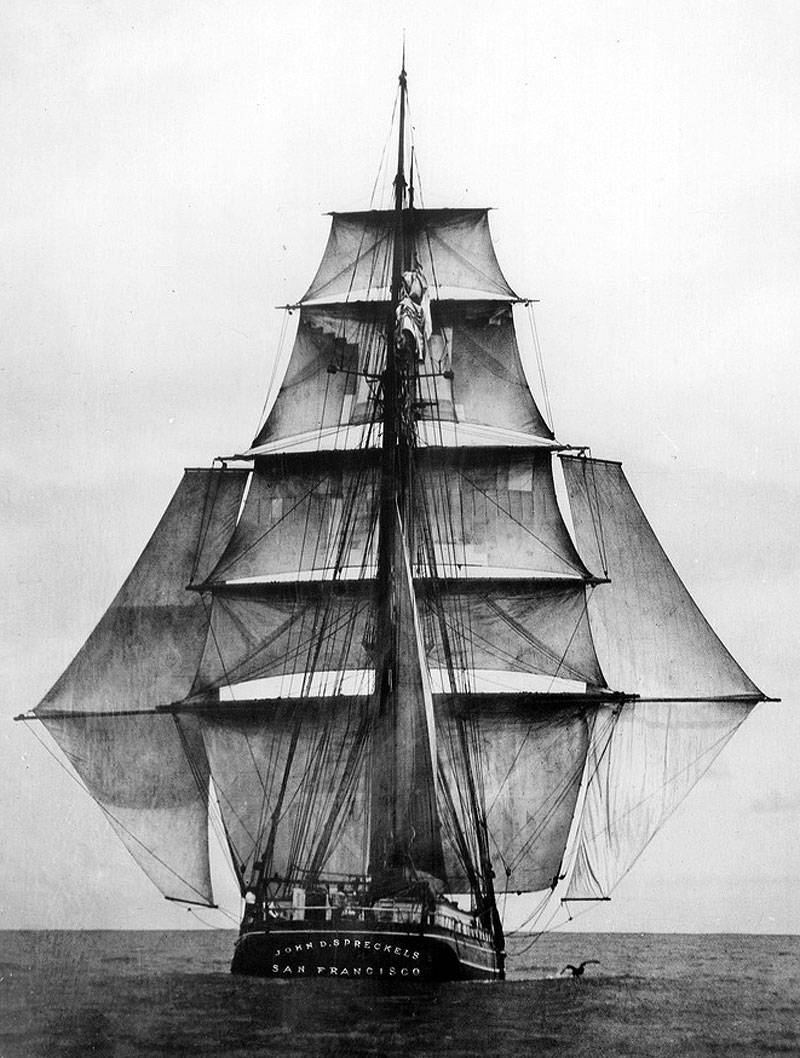

While still a bridegroom, John D. had built a little schooner named after his father. Before the Claus Spreckels gathered a barnacle, her owner was using her to solicit his father's sugar business, which he obtained by underbidding other lines. He then built a vessel named after himself. With those early profits Spreckels increased his fleet until it numbered nine.

John D. Spreckels under sail, 1880s.

Photo: State Library of Australia

John D. found that towage was costing him too much in San Francisco Bay, where the Red Stack Tugboat Company had a monopoly. He formed the Black Stack Tugboat Company and a war began off San Francisco Heads as rival tugs fought. The tow-boats went out to sea and, ranging alongside incoming vessels, slashed their rates in an effort to get business. Clusters of the tugs were always lying near the Golden Gate, ready to niggle for a job in waters that had ever been a squabbling-ground for the Whitehall boats of crimps, as well as those belonging to honest solicitors of the meat and supply houses. Among the boatmen watching that tug war was "Hook-On" Crowley, known for his aptness in hooking on to moving ships. His son Tom would one day own the Red Stacks.

Finally, bled by their warfare, the Red and Black Stacks reached an agreement to share the port's towage. In their respective offices the daily shipping journal, the Guide, had its arrival lists underlined alternately in black and red ink to allocate each ship.

Having tugs and sugar ships, John D. bought into his father's business, getting thirteen thousand dollars' worth of stock for three thousand dollars. In the eighties he branched out in shipping by chartering the freighter Suez and building the steamers Alameda and Mariposa. The latter vessels were 3,000-ton sister-ships and with them John D. reached south from Hawaii to Papeete, Tahiti, and other South Sea Island ports.

The Mariposa underway in 1883.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In 1885 those two oceanic liners were running to Australia opposite ships of the British Union Steamship Company. At the turn of the century Spreckels bought the new 6,000-ton liners Sierra, Sonoma, and Ventura and placed them in the trade. Single-funneled, sixteen-knot steamers, they maintained a tri-weekly service to the antipodes from San Francisco. They were great money-losers. Profits from " down under " awaited the coming of William P. Roth in 1926.

Spreckels's next craft was the 47-ton yacht Lurline, in which he sailed out of San Francisco in 1883 for San Diego to concentrate on the development of that port.

Originally published in Golden Gate: The Story of San Francisco Harbor by Felix Reisenberg, Jr., Tudor Publishing Co., New York: 1940