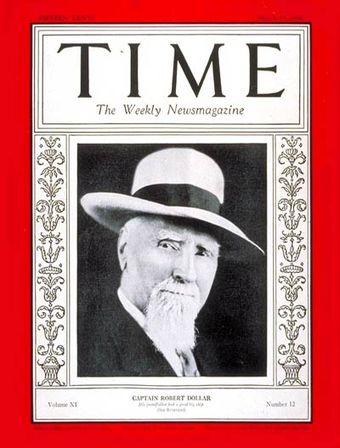

Captain Robert Dollar

Historical Essay

by Felix Reisenberg, Jr., Originally published in Golden Gate: The Story of San Francisco Harbor by Felix Reisenberg, Jr., Tudor Publishing Co., New York: 1940

Robert Dollar made the cover of Time on March 19, 1928.

Image: wikimedia commons

There started the greatest of American overseas lines, the Dollar Steamship Company, whose founder was then rising sixty years of age. Success had come late to Robert Dollar, for which he always professed to be grateful.

Dollar was the son of a lumberman; his uncle, John Melville Dollar, was of the sea, having been master and part owner of the ship Helen Drew in the Calcutta to London run. That ship was lost at sea in 1844, the year of Robert's birth at Falkirk, Scotland, and the family did not go down to the sea again for half a century.

His father's drinking sent the Dollars to America, and Canadian lumber camps hid young Robert until he was twenty-two years old. He had learned "writing and figures" after work, during the long winter nights, and came to head a gang of forty men running logs down the Dumoine River to the Ottawa. It was then that he started a diary, which he kept ever after and which enabled him to start a globe-girdling steamship line.

In 1872, at the age of twenty-eight, Dollar was losing money fast in the bad times. A decade later he moved to Michigan, looking for bigger and better timber that could be shipped to England. There he founded Dollarville and cleared the land of trees. Meanwhile he had married and was raising a family.

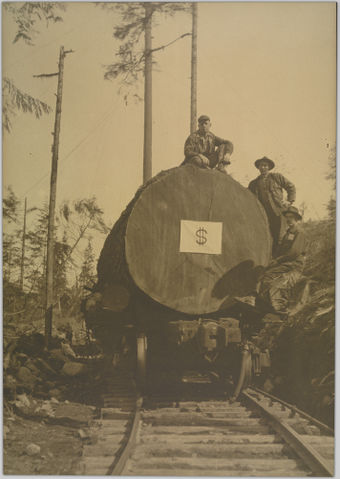

Robert Dollar Company timber harvest.

Photo: wikimedia commons

In 1888 poor health sent him west in search of a warmer climate, and the family settled in San Rafael near the shores of San Francisco Bay. With money gained from the sale of his twenty thousand acres in Michigan, Dollar bought land in California's "Redwood Empire" and in 1893 started a mill and lumbering business at Usal, Mendocino County. He too looked westward and was lured by the Pacific. In his Memoirs the Captain, called so as a matter of courtesy, explains how he started in the steamship business: "During this time [1893] I found it very difficult to get vessels to carry our lumber so I started investing in vessel property."

His first craft, the steam schooner Newsboy, plied along the coast, her home port San Francisco, where Dollar had opened a modest office. Other small craft followed the Newsboy. Dollar then became interested in a large mill at Mukilteo, near Everett, Washington, to supply cargoes for the ships he had decided to send to China and Japan.

The 5,000-ton Arab, his first ship in the China trade, carried "about half a cargo at a very low rate, which did not pay, thereby losing money at the start." Dollar, not a man to lose money, decided that if he was going into business it would be necessary to have an organization.

A year later, in 1902, Dollar made a voyage to the Orient, the first of many, and returned with six oak railroad ties and the conviction that there was a great future for him in the transpacific shipping business. Those ties were the first taken from Japan, and contracts were made for the delivery of large quantities to Southern Pacific. At the same time the Captain arranged to deliver fir ties from the Pacific Northwest to Tientsin, China. The shuttling of ties developed into a "large and satisfactory business requiring many steamers."

There was no keener student of trade than Robert Dollar, who scoured the East Indies, China, Japan, and the Philippines for information. In his diary he made pertinent notes for future use, together with the ever present record of miles traveled each day. Dollar predicted, among many things, the end of flour shipments from San Francisco to the Far East with the completion of the Siberian railroad. An avid reader of the Bible, he attributed to its teachings his success and knowledge; during his life he gave away many Bibles as gifts. In 1904, during the Russo-Japanese War, Dollar concluded one of the many deals that were characteristic of his career. He had chartered the M. S. Dollar to the Russian Government for carrying cargo from San Francisco to Vladivostok, insuring her for $180,000 against loss from war risk. This sum was paid him promptly when the Japanese seized her. After she had been used a few years as a troop ship, the M. S. Dollar was put on the block and it was the Captain who bought her back—for $55,000. He was a lucky trader.

There was a steady increase in Dollar business up to and through the World War. His sons R. Stanley and J. Harold were groomed to succeed the old man, who meanwhile traveled all over the world studying the "trades of peoples" and the trends of cargo, wondering if he could span the globe with ships.

The two older buildings in the foreground are the Robert Dollar Building (left) and the J. Harold Dollar Building (right), still standing in July 2020.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The Robert Dollar Building façade and main door. On the top floor, the corporate conference room is completely made of inlaid wood, originally built by ship joiners in the employ of Dollar lines.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The J. Harold Dollar building façade.

Photo: Chris Carlsson