Captain William Matson

Historical Essay

by Felix Reisenberg, Jr.

William Matson, 1880s.

"Lurline" was destined to remain in the history of San Francisco Harbor. It was then the name of the little daughter of Captain William Matson, who had just entered the Hawaii sugar trade.

Bill Matson, born at Lysekyl, Sweden, in the year of the gold rush, first went to sea at the age of ten, but was hauled back ashore by his parents to continue school. In 1863 he cleared from his home forever as "boy " in the Nova Scotian vessel Aurora bound for New York, where he joined the Bridgewater to voyage round Cape Horn. Arriving at San Francisco in 1867, he signed on the old coaster John J., was later in the Oakland, and in two years rose to command of the schooner William Frederick, carrying coal from Mount Diablo to the Spreckels Sugar Refinery at Eighth and Brannan streets. While skipper in the lumber schooner Mission Canal, thirty-three-year-old Matson attracted the attention of his employers. Claus Spreckels had confidence in this broad, heavy man whose penetrating blue eyes and commanding appearance made him stand apart from the many skippers in the coastal trade.

In 1882 Matson was able to borrow from Spreckels to buy shares in the 200-ton schooner Emma Claudine. Commanding her, he cleared for the Hawaiian Islands with a miscellaneous cargo selected by himself, and sailed homeward with sugar.

The Emma Claudine in a contemporary oil painting.

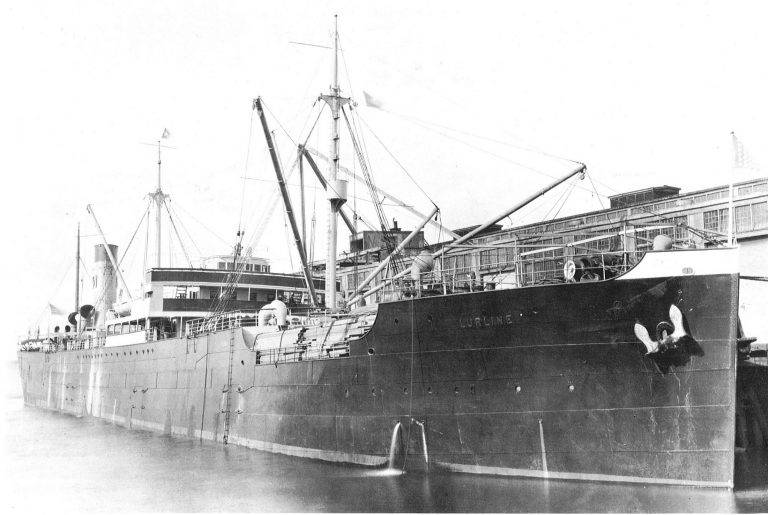

Profits from five years of Hawaiian trading went into the Captain's second ship, the 359-ton brigantine Lurline, first of three merchant ships to bear that name. The little craft, launched from the yard of the well-known Benicia builder Matt Turner, was as distinctive a vessel as any entering the Golden Gate. Marked by her long bowsprit and tall masts, she crossed a skysail yard and carried 640 tons of sugar. The Lurline earned well.

The Lurline 2, Matson's second merchant ship named after his daughter.

On early calls to Hawaii the Captain laid plans for a great line. By the nineties he was assembling a fleet of sailing ships; the little steel bark Santiago, the old Clipper Antelope, the famous Falls of Clyde, and the bark Roderick Dhu were among the first vessels of the Matson Navigation Company.

Falls of Clyde, an early Matson line ship.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

While the grain fleet was carrying wheat to Europe and the Octopus was becoming more hated, Captain Matson's star was rising over the waterfront of San Francisco. His vessels, like those of most shipmasters turned owner, were kept in first-class order. Matson, a strict disciplinarian, came down on the skipper who allowed his command to look slovenly. He also kept a weather eye on the time of passage. A master more than twenty days from Hilo knew that he was slated for a dressing down. Captain Matson would arrive at the wharf behind a high-stepping pair of horses, board the ship, and for an hour have the skipper on the carpet. But after it was over, the Captain was likely to invite his reprimanded master to dinner and the hard words would be forgotten.

On the docks Captain Matson was regarded as a Beau Brummel and elsewhere in the city he was known as one of San Francisco's smartest dressers. Every day, before driving to the wharf in the business buggy, the Captain stopped to get a fresh red carnation.

Among Matson's friends was Will Crocker, the banker. From him the Captain was able to borrow large sums on his word alone, the customary method of doing business in that day. At least twice during his career, when he lost his fortunes, Matson was rescued by Crocker. This Swede shipowner was liberal with his money, only demanding that he receive the best for the dollar he paid out. Personally he inspected supplies and meat going aboard his ships and tasted the food; seldom was he swindled twice.

Captain Matson's interest always stayed with his ships. Wealth brought him into society and he was to be seen at various functions or driving his fine horses through Golden Gate Park, but more often he was on East Street. Even after branching out in steamers he still remained active in their operation. The distinctive, brick-red paint which marks all Matson ships day (except the passenger liners) was the Captain’s invention, mixed down on the dock after hours of experiment.

Before the end of the nineties Captain Matson had bought Hawaiian Island property and was sending his ships to the various ports in the group, especially Hilo. Hawaii was fast becoming the focal point of Pacific Ocean trade, and Captain Matson was on his way to join John D. Spreckels and the British in controlling it; the ramifications of Hawaiian business are numerous and all the effects of America's taking it over in 1898 still remain untold.

Matson spread out in other directions, sinking money anchors of the line into California oil land, foreseeing the future need for this fuel in Hawaii, and believing that petroleum would one day replace coal and wood at sea. After 1900, when he started adding steamers to his fleet, Matson was among the first to urge that oil be carried in ships. On Washington trips he recommended that the Government approve deep tanks, then a losing fight because of the great fire hazard. The Captain's prediction that ships, equipped to carry fuel would be valuable in war was proved in 1918, the year after he died.

The end of the nineties, when Matson abandoned sailing ships, closed the opening chapter of the line's history.

Originally published in Golden Gate: The Story of San Francisco Harbor by Felix Reisenberg, Jr., Tudor Publishing Co., New York: 1940

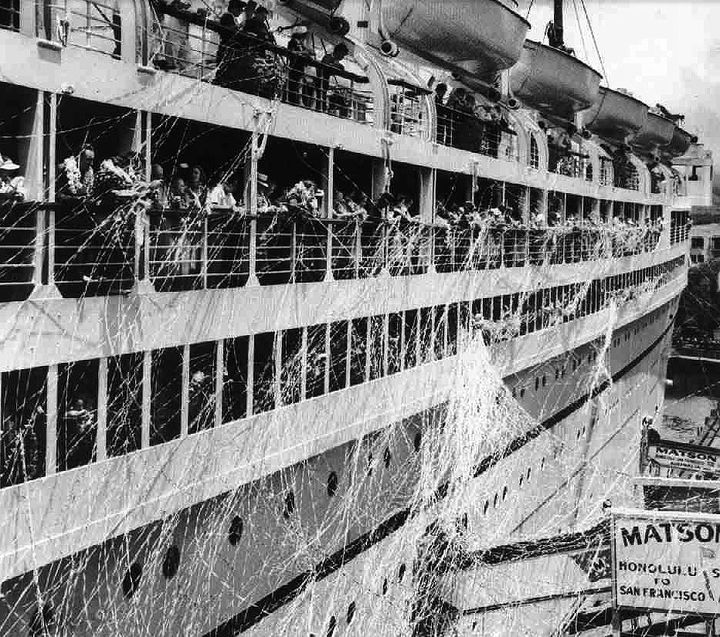

Disembarking on Matson lines during WWII.

The Lurline in San Diego harbor, 1940s.

Matson’s role in Containerization

Photos and text courtesy Matson Line website

On August 31, 1958, Matson’s S.S. Hawaiian Merchant departed San Francisco Bay carrying 20 24-foot containers on deck. The historic voyage marked the beginning of an ambitious containerization program that achieved tremendous gains in productivity and efficiency from the age-old methods of break-bulk cargo handling. The container freight system that Matson introduced to Hawaii in 1958 was a product of years of careful research and resulted in the development of a number of industry innovations that became models worldwide.

The company’s historic contribution to the maritime industry is prominently featured in an exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., entitled “Transforming the Waterfront.” The display includes authentic 1970-era Matson containers, with a backdrop mural of Matson’s Oakland container yard at night. The exhibition also addresses the impact of containerization on West Coast waterfront operations, including the historic Mechanization and Modernization Agreement of 1960. To learn more about the exhibit, please click here.

Containerization brought the greatest changes to water transportation since steamships replaced sailing vessels. And it came just in time to save the American Merchant Marine from going down with all hands under the burden of rapidly-rising costs and foreign flag competition.

Matson’s containerization program for Hawaii was the product of its in-house research department, which was established in 1956 and was the first of its kind in the industry. It was a tremendous program, perhaps one of the most significant ever undertaken by an ocean carrier.

The transformation of the Matson fleet from break bulk to container vessels began in 1960, when the S.S. Hawaiian Citizen became the first vessel in the Pacific to be converted to a full containership. It was also the first vessel to incorporate a large-scale refrigerated container capacity into the company’s regular container service. While other vessels were converted in the early 1960s, construction of the first containership in the world to be built from the keel up commenced in 1967, from a design developed by Matson’s own naval architects.

The first true containership, the Hawaiian Enterprise.

That vessel, the S.S. Hawaiian Enterprise (renamed Manukai), and its sistership, the S.S. Hawaiian Progress (renamed Manulani), entered service in 1970 and marked the beginning of a new generation of containerships. The gains in productivity and efficiency were remarkable. In 1950, an average commercial vessel could carry 10,000 tons at a speed of 16 knots. Following the development of containerization, the average commercial vessel carried 40,000 tons at a speed of 23 knots. Concurrently, shoreside innovations were introduced, including the world’s first A-frame gantry crane, which was erected in 1959 in Alameda, California and became the prototype for container cranes. In addition, Matson introduced the first transtainer by Paceco and the first straddle carrier in the world by Clark Ross—both developed to meet Matson specifications.

The straddle carrier, a Matson innovation.

The Hawaiian Progress begins its maiden voyage from Oakland to Hawaii in 1970.