Midcentury Migrations

Historical Essay

by Tomás F. Summers Sandoval Jr.

Mexican immigrants at border check during 1940s Bracero program.

Latin Americans migrated to the city in increasing numbers during and after World War II. The agricultural industry encouraged the migration of hundreds of thousands Mexicans to California, with direct consequences for the Spanish-speaking community in San Francisco.(77) With its port and factories often providing greater job opportunities than the fields, the city drew migrant laborers from the farms in the Salinas, San Jose, and San Joaquin Valleys—places one author termed well within the “sphere of San Francisco.”(78) Migration to the city in this period benefited from older trends as well. During the Depression, more than 300,000 “white” workers migrated to the West from the fields of Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas. By 1934, 142 agricultural workers existed for every 100 agricultural jobs.(79) By comparison, the industrial and transportation base of San Francisco’s economy left it with “one of the lowest rates of unemployment of any large city and . . . a higher standard of relief.”(80) Indeed, by 1930 more than 37 percent of San Francisco’s economy was in either manufacturing or transportation, while as a port, it handled more than 80 percent of the state’s agricultural output.(81) San Francisco, of course, benefited in multiple ways from the massive irrigation projects transforming the once arid lands of the San Joaquin Valley into thriving agricultural plantations, canning, processing, and moving much of the resulting output—which itself accounted for some 40 percent of the U.S. total.(82) The movement of people was a residual effect. As early as 1919 one official with the California Commission of Immigration and Housing observed that a “very large percentage of the Spanish and Mexican laborers of San Francisco are migratory, here during the winter months and in the fruit and agricultural fields the balance of the year.”(83)

For many agricultural laborers, San Francisco represented the urban destination point with a larger corrida, or migratory circuit. The Moreno family migrated from New Mexico in the late thirties. The parents lived out of their car as they picked crops to earn money en route, the circuit of agricultural work transporting them far beyond the home they once knew. “They picked all the way to Half Moon Bay,” their daughter Dorinda recalled.(84) Life in the fields and, later, in the cities of California, allowed the family to progress economically. By the early fifties, they had saved enough to buy a house. But “we still picked,” Moreno remembered. “We’d still go out on the weekends and whenever there was no school.”(85) Similarly, Rosa Guerrero crossed the border at El Paso as a small child but was raised in Reedley, a small agricultural town in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Growing up, she “worked the fields to earn money while she was going to school so everything she had she paid, she earned it.” While in high school, she visited San Francisco during the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition. And “she fell in love with the city. She said, ‘Oh, I want to live here.’ ” After she married, she and her husband settled in the city, where they raised their family.(86)

Wartime industrial expansion drew workers from the fields in even greater numbers. Providing job opportunities and newly built “temporary” housing units for wartime laborers, communities like Hunter’s Point were home to more than 35,000 newcomers.(87) For many, these units represented a move up from the poverty they had known in the fields. For those already accustomed to city life, the units provided affordable rents and proximity to work. With both a mother and an aunt working in the wartime industries, Sam Rios and his family qualified for this housing when they relocated to Hunter’s Point. The community “was like family,” said Rios, recalling the other Mexican families that lived nearby. However, with the presence of Filipino, black, and Anglo families, wartime housing created something beyond a Latino enclave. “It was a mixed community.”(88) The shipping ties that predated the war allowed that industry to recruit workers heavily from Central America, especially Nicaragua and El Salvador.(89)

In addition to attracting thousands of new Latinos to the city, the war also changed the community of those already established there. New housing and employment opportunities allowed many families to “get a leg up” during the war.

The stories of professionally trained Latin Americans who made San Francisco their permanent home encompassed many of the same themes as the experiences of “unskilled” labor migrants throughout the twentieth century. When Martin del Campo, an architect from Guadalajara, immigrated to the United States with his wife and two daughters in the 1940s, he moved to Detroit. Del Campo’s wife—a U.S. citizen who had met him while studying art at the Academia de San Carlos—had roots in Michigan. But Los Angeles had been his “first idea,” and del Campo was generally unhappy with his new life in the upper Midwest. So when a coworker began touting San Francisco over a period of months, del Campo finally broke. “I thought, well, why shouldn’t I go to San Francisco?” It was a decision he never regretted. “It was a revelation. Not only did I love the town, but I loved the atmosphere, the people. . . . San Francisco has great attraction to Mexicans. It has such perfect weather and such tolerant attitudes.” The Golden Gate provided a fresh start for the family of four, especially the young del Campo, whose artistic trainings and leftist political leanings had made him feel like an outsider in the architectural professional community of the Midwest. “[San Franciscans] were very liberal in their views,” he found. “I felt very happy in San Francisco.”(90)

Wagons of coffee are hauled from San Francisco docks, April 20, 1946.

Image: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

By 1950, the Central and South American–born population of San Francisco had risen to 5.6 percent of the total foreign-born. With the Mexican-born population only representing 4.6 percent of the city’s total, the Central American presence was establishing the pattern that would come to characterize succeeding decades. From 1958 to 1960, the flow of migrants from El Salvador alone outpaced that from every other Latin American nation, with more than a third of all Central American immigrants to the city beginning their journey there.(91) Postwar salvadoreños most often came as a consequence of economic desperation and political turmoil. For example, as a nation marked by coffee monoculture, El Salvador relied on trade to export its primary crop as well as to import the majority of the beans, corn, and other foods necessary to feed its population.(92) This would naturally connect the nation to the rest of the world via shipping routes; its coffee connected many of those routes to San Francisco. With a military government in control of a class-stratified and economically unstable society, the El Salvador of the 1950s and 1960s offered little chance for advancement. Migration, whether direct or in stages, presented one solution. As the San Francisco population of salvadoreños grew, it attracted succeeding waves. When a conservative regime overturned the 1972 election of leftist José Napoleón Duarte and ushered in a renewed period of repression and strife, and when conflicts erupted into civil war nearly a decade later, thousands more used the preestablished networks between Central America and the Bay Area.

Similar forces framed emigration from Nicaragua to the United States. A military dictatorship took power in Nicaragua in 1932 on the heels of a U.S.-backed assassination. General Anastasio Somoza García ruled the nation for more than a quarter of a century before handing power over to his sons.(93) The general political repression and economic hardship plaguing Nicaragua’s modern history promoted movement as well. A mid-1960s study of Nicaraguan immigration to San Francisco found that most respondents came to the United States for the economic opportunities, while another large percentage had fled political persecution.(94) Several postwar transportation developments facilitated Nicaraguan immigration. In addition to already established shipping lines, airlines provided service between Managua and San Francisco as early as the fifties. A one-way ticket cost approximately $185 in 1960.(95) The results were palpable. The U.S. Census listed as many Nicaraguans in San Francisco as in all of California.(96)

Since travel by other means would have meant a stopover in a city like San Diego or Los Angeles, this statistic speaks to the use of more direct forms of transport, and the ultimate lure of San Francisco, with its pre-established connections to their homelands.

Like migrants that came from all Central American nations, Nicaraguans sometimes traveled to San Francisco through Guatemala and Mexico. These patterns of migration frequently entailed trains, buses, and foot travel. During the journey of more than 5,000 miles, many things could go wrong. One Nicaraguan couple recalled their journey through Mexico with some regret. “His father had fastened the bag containing their papers and money to his wrist with a light chain. While they sat in the cathedral [of the Virgin of Guadalupe (in Mexico City)] listening to the mass, the old man fell asleep. When he awoke later and lifted his arm he found that the chain had been severed and his bag was gone. Without the papers he could not get into the States, so he had to wire his son in San Francisco, then wait until his son could send him bus fare back to Nicaragua to enable him to get a new set of papers. Naturally, the old folks had a low estimate of Mexicans as a whole after this incident.”(97) In a strange twist of fate, the same thing had happened to their son when he made the same journey years before. Whether retold as a warning to future migrants of Mexican criminality or an account of what actually happened, such tales were made believable by the difficulties of nondirect travel from Nicaragua to San Francisco.(98)

The diversity of San Francisco’s Latino community included representation from most, if not all, Latin American nations. In addition to the six Central American countries and Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic also sent statistically measurable contingents.(99) Puerto Ricans’ migration in the postwar period made them the fourth-largest group in the Latino community. A survey of Puerto Ricans leaving San Juan for San Francisco illuminates the shift in their migration process from the earlier period. The study by Ayuda Católica para Emigrantes Puertorriqueños (Catholic Aid to Puerto Rican Emigrants) sought to provide emigration information to local Catholic parishes. Assuming that the Catholic Church would facilitate these immigrants’ transition into mainland U.S. society, the group conducted research for every major destination in the United States, primarily the East Coast centers of New York, Philadelphia, and Miami. Though made statistically irrelevant by the fact that many migrants failed to answer some questions, the survey does relate vital information for forty-six Puerto Ricans who entered San Francisco between September 1956 and September 1961.(100) The majority of the Puerto Rican migrants questioned left to San Francisco to reunite with a family member or spouse. While twelve of them responded that they had never been to the U.S. mainland, most had previously lived there for at least one year.(101) Though family networks and familiarity with San Francisco seemed instrumental in creating the flow of migrants from the island to the bay, just under half of them also had jobs waiting for them upon arrival.(102) As the small sample suggests, Puerto Ricans came to San Francisco in the postwar period for many of the same reasons as other Latin American migrants. Using established familial patterns and networks, migrants made San Francisco their destination in order to be with family, find work, or just begin a new life.

Nuestra Señora Guadalupe Church construction site, surrounded by Latino residents during ceremony early 20th century.

Image: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

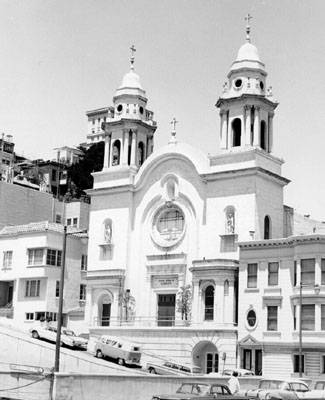

Guadalupe Church in 1964, after the building of the Broadway Tunnel had severed the old Latino neighborhood, and contributed to a major migration from North Beach to the Mission.

Image: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Guadalupe Church in 2014.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

As a new Latin America–descent population settled in the postwar city, it primarily chose the Mission District as its home. Their movement of these Latinos was partially shaped by the demise of the two early twentieth-century barrios. The North Beach–based Guadalupe barrio began its decline in the late forties. Temporarily divided by the construction of the Broadway Tunnel, this community was dislocated from itself by development. Adding to this disruption, the ethnic composition of the barrio also began to change in the postwar years as an increasing number of Chinese and Chinese Americans came to reside there. By 1960, Guadalupe Church served a congregation far more diverse than just the Spanish-speaking. The South of Market barrio went into a partial decline in the mid-1930s with the construction of the Oakland Bay Bridge, completely displacing the part of the barrio around Rincon Hill.(103) A more general pattern of southward migration accelerated the effects of displacement, with more Latino residents in South of Market migrating southward along the city grid, into first the North Mission, then the Inner Mission. Replicating a pattern established by earlier waves of Germans, Irish, and Scandinavians, Latinos settled an area close to where they had entered the city, and then migrated into the working-class bastion that was the Mission.(104)

The Rios family moved to the Mission before the war, when the opportunity to own a home presented itself. Growing up in the vicinity of 21st and Harrison Streets, Sam Rios remembered that certain sections of the district had a Latin American identity from the late 1930s. “When I was a kid I used to run up and down 24th Street. And you hardly ever heard anybody speaking English. It was all Spanish. 16th Street was like that, 21st Street was like that, 7th and Mission. . . . You knew they were Mexican enclaves.”(105) Though most were not homeowners, more and more Latinos settled in district. Even for those with more migratory life experiences, the district became the center around which their movements revolved. “We went in and out of the Mission. No matter what we did we’d always end up back in the Mission.”(106) And they were not alone. Between 1950 and 1970 the “Spanish-surnamed” grew from 11 percent of the district’s population to more than 45 percent, making the Mission District the primary Latino barrio in the city.(107)

Many Latinos worked in the city’s shipyards, canneries and produce packing warehouses, slaughterhouses, and other factories. Some of these employers—like the Levi-Strauss factory—were located in the Mission, while most others were nearby. The port lay just north, a short ride up Mission Street on the number 14 bus. The same area housed a variety of fruit and vegetable packing warehouses.(108) Most of the canneries were in the Mission District, down 18th Street and on Mariposa, while the slaughterhouses thrived in nearby Hunter’s Point.(109) Out of the fourteen largest manufacturers in San Francisco, only two were outside of the Mission or the South of Market region just to its north.(110) Unfortunately, the postwar wave of Latin American workers settled in a city undergoing a general decline in its manufacturing base. From 1947 to 1963, during the first phase of a general boom in the San Francisco economy, manufacturing jobs in the city decreased by 21 percent.(111) This decline in manufacturing was part of a larger shift in the Bay Area, as blue-collar jobs left San Francisco for the four surrounding counties. From 1958 to 1967, while the city lost some 7,000 manufacturing jobs, the surrounding counties gained more than 28,000.(112)

These trends, presaging more of the same in later decades, made the city an increasingly difficult place for a working-class family to survive, and yet they did little to curb the postwar migration boom.

Most Latino families who survived in the city did so because they found work. Many, like the Rios men, found employment in the shipyards, which largely provided a stable income and an increase in job skills. Taking advantage of the shortages created by war, both their wives also found work in the shipyards during the forties.(113) Esperanza Echavarri’s father worked at a butcher shop on 3rd Street. She remembered that “we’d always have meat that he’d bring, every piece of the meat we ate—because they ate it all.”(114) Like many other women, Josephine Petrini worked in the canneries. Sometimes pulling a double shift, Petrini could work up to twenty-hours straight in an attempt to provide for her family. She even performed her sometimes grueling job while she was six months pregnant with her son, evidence of both her financial need and her sense of dedication.(115) Factory work also connected Latinas and Latinos to other working-class people of color. As Petrini recalled, Chinese workers stood side by side with the Spanish-speaking in her assignment. Dorinda Moreno’s mother likely experienced the same while working at local fish canneries.(116)

Rather than work for someone else, some Latinos and Latinas built businesses of their own. Sam Rios’s grandmother, a self-sufficient woman who provided for her family, reflected some of the ways Latinos created their own opportunities. “She started a little tortilla factory right on 21st and Harrison. And so her and her comadres they used to sit around this comal and make tortillas by hand. And they would go door to door and sell them. So little by little, they built up a business. . . . My grandmother was always the strong, stable person in the family.”(117) After migrating to the city with her husband and three daughters, Guadalupe González was disappointed with the job opportunities for a monolingual Mexican immigrant woman. She began taking English classes and attending beauty school. After graduating, she “found out that they were only willing to give her a job as a shampoo girl,” so she decided to open her own shop in the Outer Mission. Every Saturday, her daughters had to choose how to help out. “Our choice was, you go to the beauty shop and you work all day or you stay at home and clean the house and cook dinner. So it wasn’t much of a choice, okay?”(118)

Work patterns often mirrored migration networks, as Latin Americans used kinship networks to navigate the city. When one Salvadoran family came to the city with their small child, they lived with a Costa Rican–Mexican couple the young girl thought of as “padrinos.”(119) They resided in the South of Market barrio, on Boardman Place, where Spanish-surnamed tenants occupied most of the housing.(120) Later, the girl’s mother, aunt, and their comadres all found employment working as domestics in a local nursing home, depending on each other for economic and social support.(121)

Interpersonal connections were often the foundation of community. When Esperanza Echavarri’s family left the fields and came to the city, her father “had a family relation who knew his family [and] that settled here in San Francisco.” The family moved in with them for a few years, until they could afford their own apartment in the South of Market area. The matriarch “was always very connected to us. She was always over for our celebrations, and always my mom maintained a very close connection with her.”(122)

Notes

77. For historical accounts of the roots, process, and effects of the labor systems affecting Mexican migrant workers, see Hernández (2010); and Gilbert G. González (2006).

78. Rosskam, 56.

79. Starr, 67.

80. Kerr (1939), 75.

81. Mullins, 8.

82. Sánchez, 19.

83. Frank J. Palomares, “Preliminary Report, January 1919,” California Commission of Immigration and Housing, Department of Industrial Relations, Division of Immigration and Housing Records, 1912–39, folder 24, BANC.

84. Dorinda Moreno, interview with author, March 6, 2002, Concord, CA.

85. Ibid.

86. Echavarri interview.

87. Nash, 67–68.

88. Rios interview. In a city that still functioned with a high degree of social segregation, the housing at Hunter’s Point may have created some of the first large-scale diverse communities.

89. Godfrey (1988), 140.

90. Martin del Campo, interview with Marilyn P. Davis, n.d., San Francisco, in Davis, 272–74, 276.

91. Figures compiled by International Institute, 1961, quoted in Stirling, 14. Out of a total of 2,481 immigrants to the city, coming from the six Central American nations of El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Panama, and Honduras, 834 were Salvadoran.

92. Galeano, 112.

93. Ibid., 124–25.

94. Stirling, 4–5.

95. Ibid., 6. A majority of the interview subjects who form the sample of this study arrived in San Francisco by air.

96. Ibid., 7.

97. Ibid., 6.

98. Strong cultural rivalries exist between Nicaraguans and Mexicans, a reflection of which may possibly be observed in this tale of migration. See below.

99. U.S. Census charts for 1960, in Stirling, 1.

100. Files of Ayuda Católica para Emigrantes Puertorriqueños, Puerto Rican Migrants file, AASF.

101. Ibid. It should be noted that nine respondents failed to answer the question.

102. Ibid.

103. Godfrey (1988), 148.

104. Ibid., 140.

105. Rios interview.

106. Moreno interview.

107. U.S. Bureau of the Census (1973).

108. Directory of Large Manufacturers, 1967–68, San Francisco. For the purposes of discussion, the data in the directory was compiled by author. A spreadsheet was made listing all 98 of the manufacturers that listed 500 or more employees. Included were their addresses, principle industry, and head executive.

109. Josephine Petrini interview, in Camplis. Slaughterhouses were located primarily along 3rd Avenue in the part of town known as “Butchertown.” In addition to Latinos, African Americans represented a major component of their labor force. See Tomás F. Sandoval.

110. Directory of Large Manufacturers.

111. San Francisco Conference on Religion, Race, and Social Concerns, 9.

112. Ibid., 9.

113. Rios interview.

114. Echavarri interview.

115. Petrini interview, in Camplis.

116. Moreno interview.

117. Rios interview.

118. Sanchez interview.

119. Interview with Helen Lara Cea, by author, October 10, 2001, Berkeley, CA.

120. Polk’s San Francisco City Directory, 1689. This is further suggested in the community’s collective memory.

121. Lara Cea interview.

122. Echavarri interview.

excerpted from Latinos at the Golden Gate: Creating Community and Identity in San Francisco, by Tomás F. Summers Sandoval Jr., Copyright © 2013 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher.