Butchertown's Beginnings

Historical Essay

Conor Casey, excerpted from "San Francisco’s 'Butchertown' in the 1920s and 1930s: A Neighborhood Social History," in The Argonaut, Vol. 18, No. 1, Spring, 2007.

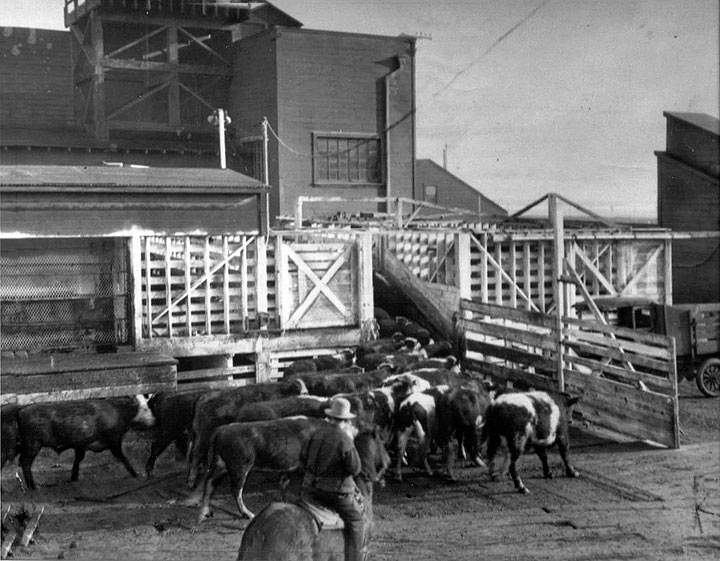

3rd & Evans, in the heart of today's Bayview neighborhood, was a brackish marsh and home to SF's second "Butchertown" until it was filled in the post-WWII era. This photo is dated January 11, 1921.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library (AAB-6727)

Evans looking east from Third, Feb. 20, 1929.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.03756

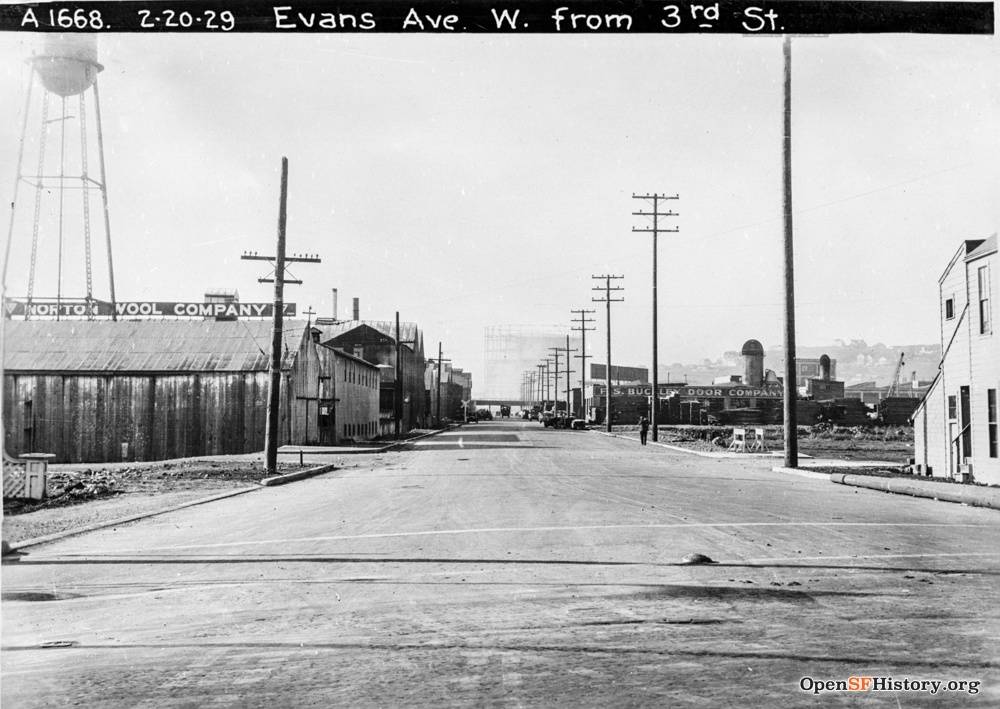

Evans looking west from Third, Feb. 20, 1929.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.03757

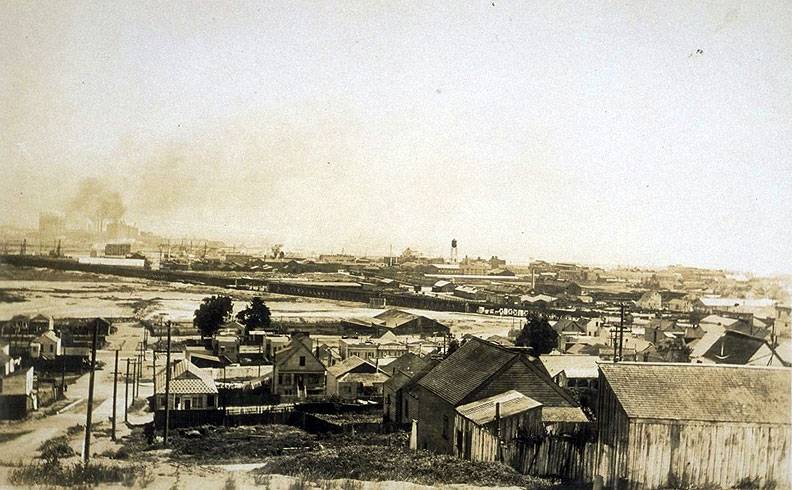

Butchertown, as seen on April 16, 1929. Cows? In SF?

Photo: Online Archive of California

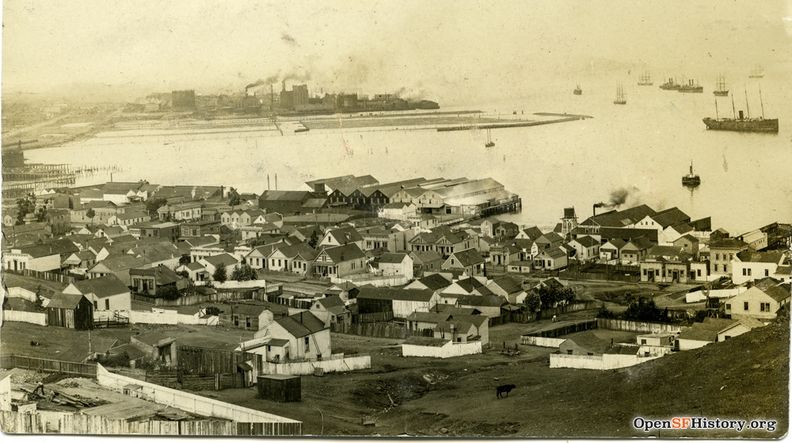

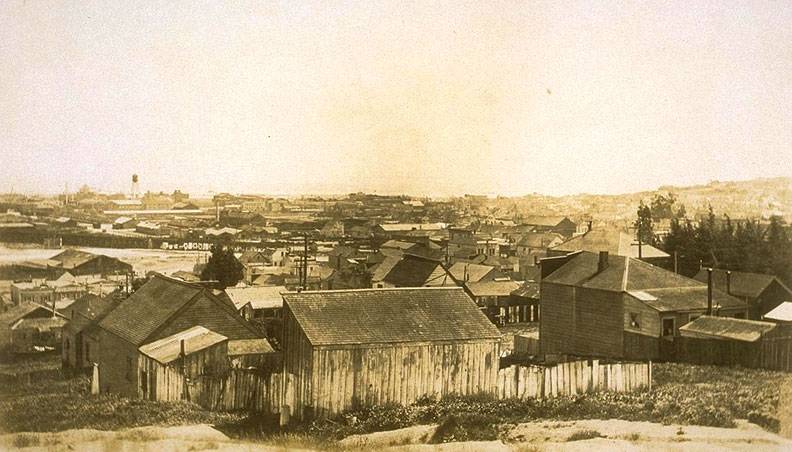

Photo postcard view northeast from hill toward Islais Creek. Fairfax Avenue, cottages, California Tallow Works, Chas. F. Lengeman shop all in the Butchertown area in foreground, c. 1915.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp27.4754

Bayview when it was Butchertown, 1920s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

| Founded in 1868, San Francisco’s Butchertown was an industrial neighborhood that housed a myriad of slaughterhouses and related industries such as tanneries, fertilizer plants, wool pulleries, and tallow works. Located in the Bayview sector of San Francisco, Butchertown’s unique urban geography coupled with the area’s proximity to an abundance of water and open land, allowed for the flourishing of commerce. Additionally, the richness of economy, diversity of residents, and vibrancy of community sustained Butchertown’s powerful and close-knit neighborhood identity through to the closing of the last slaughterhouse in 1971. |

In 1868 a group of butchers purchased eighty-one acres of submerged and waterlogged tidelands from the State of California to establish a "Butchers' Reservation" for slaughtering animals. Filled with marshes, creeks, and bayside mud flats, this area of southeastern San Francisco had remained largely undeveloped despite several attempts at residential housing ventures during and after the California gold rush.(3) The butchers had been forced to the outer fringes of town by an ordinance that banished the slaughtering of animals — and the smells, sounds, and carnage that went with the process — from the city center. An abundant water supply and the area's relative isolation must have appealed to the meat men: offal from butchering could be easily disposed of in the ebb and flow of bay tides or the area's meandering creeks; isolation reduced the chance of another forced relocation when city development encroached.(4)

By 1877 all eighteen of the city's slaughterhouses had relocated to the Bayview sector of San Francisco. Related industries quickly followed: tanneries, fertilizer plants, wool pulleries, and tallow works joined the industrial community of the area that San Franciscans would call Butchertown.(5) Workers came with the industries; the greatest number of neighborhood residents worked in the surrounding industrial plants of the area. Though some residential development had preceded the butchers' move into the area, sustained development of land was a result of the jobs the Butchertown industries created.(6)

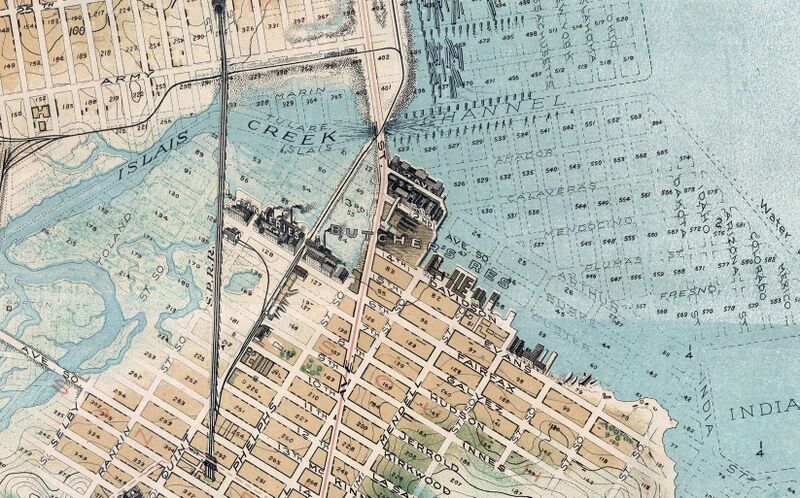

The 1913 Chevalier map showing the location of the "Butcher's Reservation" on the southern edge of Islais Creek where its wetlands met the bay near 3rd Street.

Map: courtesy David Rumsey Map collection

Butchertown along the shore.

Photo: Online Archive of California

Charles Rosenberg, Wholesale Butcher, 1920s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

Butchertown facility.

Photo: Online Archive of California

The Butchers' Reservation was bounded by First Avenue South to the north (present-day Arthur Avenue), I Street to the east (present-day Ingalls Street), Railroad Avenue and Kentucky streets to the west (present-day Third Street), and Bayshore to the south.(7) The surrounding area of housing and businesses, including the Butchers' Reservation, was the area known as Butchertown. Thus, Butchertown became an industrial suburb within San Francisco's city limits.

Butchertown's heyday was over by the 1906 earthquake. However, slaughterhouses in the area remained for more than sixty years after the earthquake. The last slaughterhouse closed in 1971.

Butchertown's relative isolation from the main body of San Francisco and its unique urban geography helped to foster and reinforce a distinct sense of neighborhood identity and community in its residents. This geography led to a combination of urban-industrial and rural-agricultural economies and a mixture of industrial, residential, and agrarian land uses. More than just geography and neighborhood businesses fostered a sense of community, however; social networks and organizations linked residents to one another across ethnic and religious lines. Unlike some other areas of San Francisco, the neighborhood's various ethnic groups lives intermingled with one another in the district.(21) This pattern of mixed housing also helped to break down barriers and to create a strong face-to-face society characterized by a sense of "neighborliness."(22)

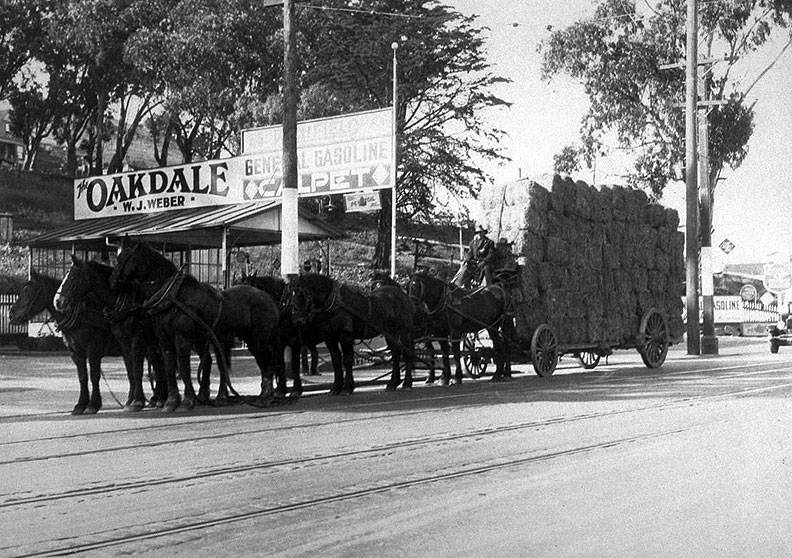

Hay wagon at Oakdale and Bayshore, 1920s

Photo: Online Archive of California

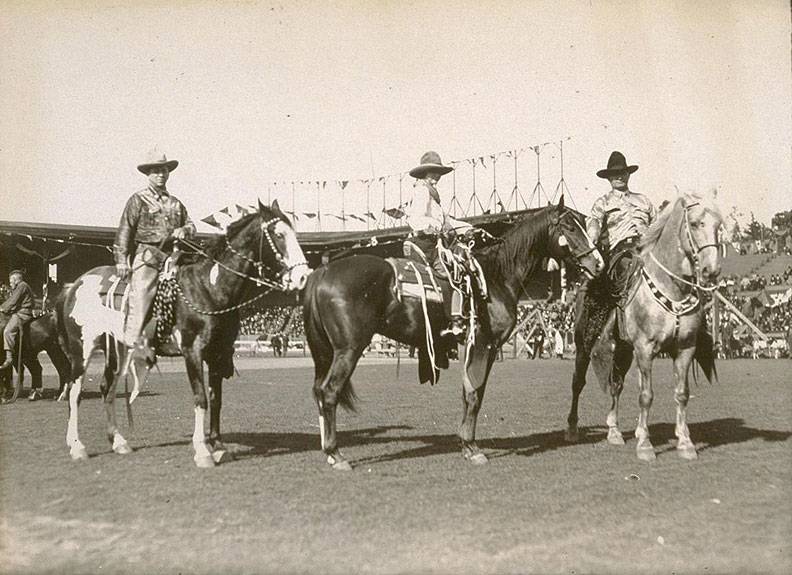

Boys from Butchertown at Agricultural Fair, 1920s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

Along the fringes of the neighborhood to the south and east, undeveloped hillsides were pasture to cattle and horses owned by small ranchers, farmers, and Butchertown's cowboys. In the southern section of the neighborhood, small vegetable farms, ranches, and nurseries took advantage of the open land.(28)

Islais Creek wetlands along railroad trestle, 1920s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

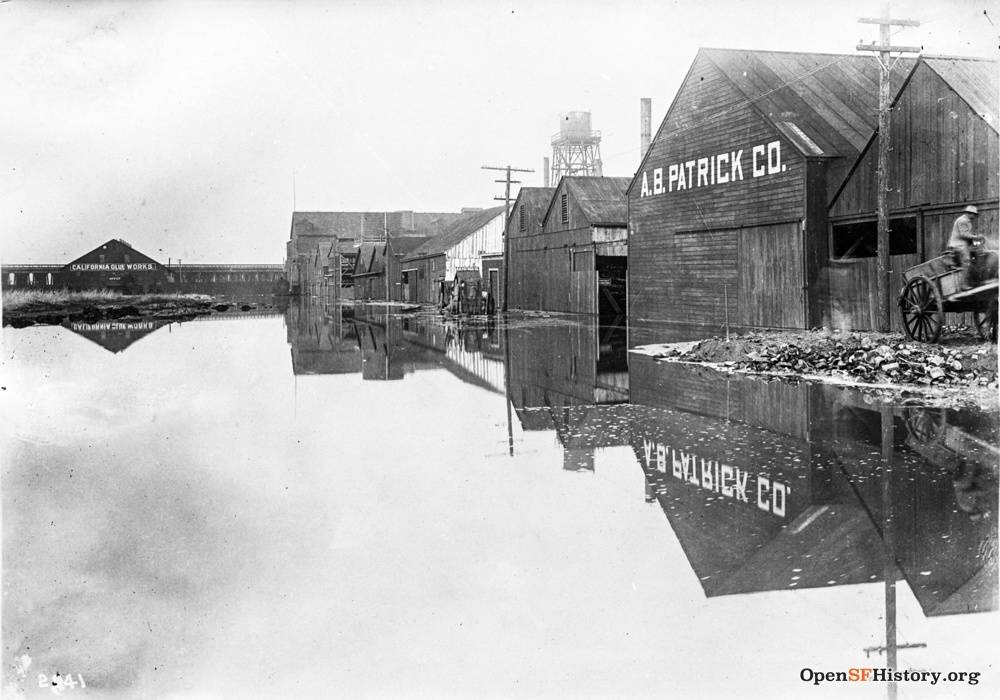

The area's proximity to plentiful water, the bay, and open land drew industries and created a unique mix of urban-industrial and rural-agricultural economies. These economies shaped the landscape according to their needs and took advantage of the natural features of the district. For example, the four main slaughterhouses of Butchertown — Miller & Lux; James Allan and Son; the H. Moffatt Company; and J. G. Johnson — were located in the northeast sector of the neighborhood along Islais Creek and the bay's edge, drawn by the area's plentiful supply of water and its distance from the rest of San Francisco. All of the slaughterhouses were constructed on pilings over the water to allow the foul by-products of their operations to be washed away by the water of Islais Creek and bay tides. The slaughterhouses maintained a network of stockyards along the western boundary of the neighborhood and on the hillsides of the southwest sector. Cowboys were a common sight, driving cattle from the stockyards along the Southern Pacific Railroad and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad tracks on the western fringe of Butchertown to the slaughterhouses to the northeast.(29)

Shipyards, a few factories, a handful of houses, and open land characterized Hunters Point throughout the 1920s and 1930s.(31)

Butchertown, 1920s.

Photo: Online Archive of California

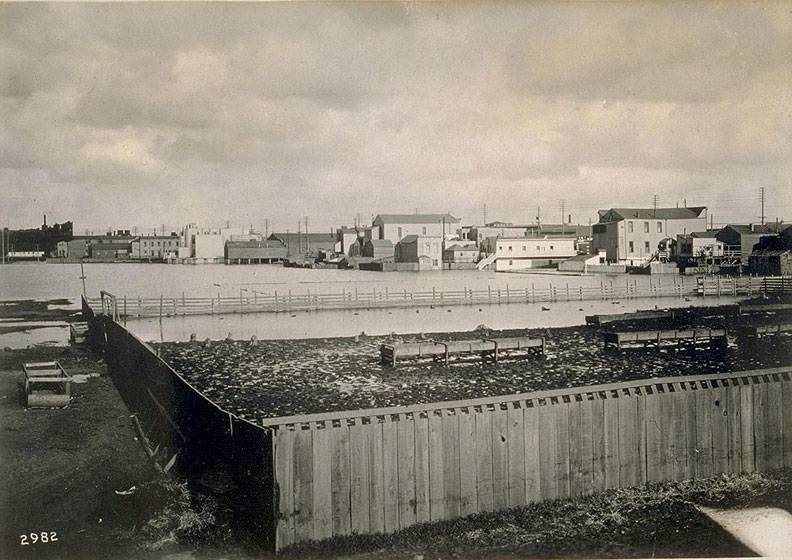

California Glue Works (back left) in Butchertown, seen here during Islais Creek flood of 1916.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.01142

Bay View's industries provided steady employment to a predominantly male workforce.(38) Many residents struggled to make ends meet, however, especially during the Great Depression.(39) Butchertown residents supplemented their diets and wages by creating a dual economy in their backyards. Most residents kept vegetable gardens, along with chicken coops, rabbit hutches, and occasionally farm animals like pigs and goats. Gardening and raising livestock represented a complementary domestic economy that augmented the wage economy. It also reinforced Bayview's distinct hybrid of rural and urban land use.

The neighborhood's close-knit community also created a distinct identity. The main ethnic groups in Butchertown were French, Italian, Maltese, and Irish Americans. Unlike other sections of San Francisco, different ethnic groups lived side by side in the Bayview with little geographical concentration in housing and without much conflict.(45)

NOTES

3. William Crittenden Sharpsteen, "Vanished Waters of Southeastern San Francisco: Notes on Mission Bay and the Marshes and Creeks of Potreros and the Bernal Rancho," California Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 21 (June 1942).

4. Roger Olmsted and Nancy Olmsted, "Rincon de Las Salinas y el Potrero Viejo-The Vanished Comer: Historical Archaeological Program, Southeast Treatment Plant," 1978-1979: Report (San Francisco: San Francisco Clean Water Program, 1981),218.

5. "Butchertown: Argument Before the Board of Supervisors For and Against the Extension of its Limits," The Daily Evening Bulletin, Feb. 25, 1878, 1.

6. Olmsted and Olmsted, "Rincon de Las Salinas."

21. All interviews, United States Census 1920, 1930.

22. Isabella Evets, interview by author. Tape recording. Pacifica, CA, Nov. 25, 2003.

28. John Mahoney, interview; Geraldine Hingsbergen, letter to Conor Casey; Antoinette De Lauff, interview; Sanborn Map. On the area's vegetable farms, see: Tom Carter, "The Last Farmer." San Francisco Sunday Examiner and Chronicle, June 21, 1970,26-30.

29. Antoinette De Lauff, letter to Conor Casey, undated.

31. "Hunters Point," 1920s. San Francisco History Center, Main Library; San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection, Folder: S.F Districts-Hunters Point-1920s. AAB-8900.

38. U.S. Census, 1920, 1930.

39. Antoinette De Lauff, interview.

45. All interviews.