Communalism in San Francisco

Historical Essay

by Matthew Roth

Listen to an excerpt from "Coming Together: The Communal Option" read by author Matthew Roth:

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/12RothComingTogether" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

by mp3.

![]()

Previous stop: La Gaceta Sandinista

Next Stop #13: The Mission mobilizes

Although communes sprouted up all over the country in the late 1960s, few regions saw more people living communally than Northern California, with San Francisco as its epicenter. Estimates of exactly how many people lived communally in this era are varied, particularly given the strong desire among many communards to eschew media and academic attention. Most scholars on the topic, however, generally agree that upwards of 5,000 communes flowered nationally during the late 1960s and 1970s, with hundreds of thousands, if not a million, people living in them.

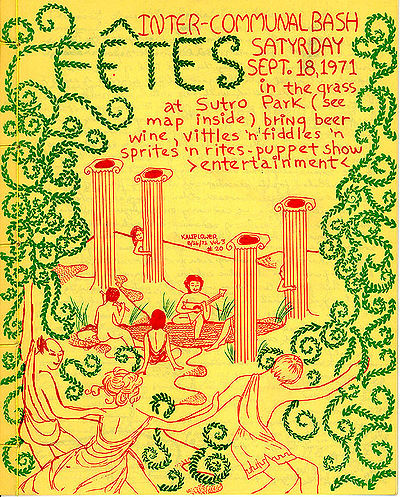

from Kaliflower

Hundreds of communes sprung up in San Francisco, Oakland and Berkeley, often composed of 10-20 people living in old Victorians, usually adopting their physical street address as their communal name. One of the more significant of these was originally situated at 1873 Sutter Street in San Francisco, and later, after they had to move because of the machinations of the Redevelopment Agency, 1209 Scott Street. The Sutter/Scott Street commune published a weekly inter-communal newsletter titled Kaliflower, which by 1971 was being distributed to more than 300 communes in the Bay Area, at least 50 of them East Bay. The newsletter was printed on a Chief 15 offset press in the in the commune’s basement, what became known as the Free Print Shop.

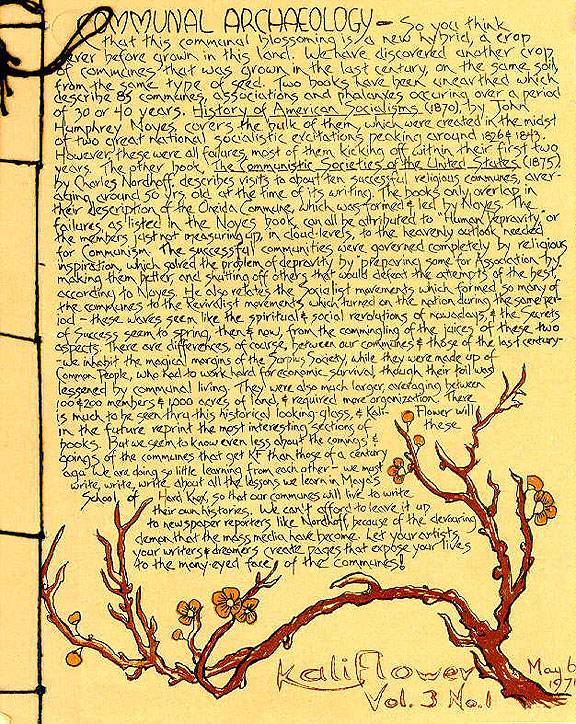

Because of the popularity and ubiquity of the publication, the commune eventually became known to most of the outside world as Kaliflower. The newsletter was published weekly by the commune from April 1969 to December 1971, and intermittently thereafter. Initially Kaliflower served as an inter-communal bulletin board, listing items needed by one commune, items offered by another, with light editorial content, and occasional poems and missives. The newsletter also contained how-to articles and skills sharing. In a Kaliflower from November 26, 1970, an article provided instructions for building cold boxes to grow food, as well as a recipe for squash soup. The Kaliflower from December 10th, 1970, offered instruction for “Yoga Nazal Cleaning” and herbal hair care. Gradually the editorial content of Kaliflower became more involved, offering historical context for modern communalism among a long lineage of American utopian experiments. In the cover article “Communal Archaeology,” from May 6, 1971, the first issue of Volume Three with a larger format, the authors acknowledge the debt the communal movement of the 1960s and 1970s owed to the Revivalist explosion of communes in the 1820s and 1840s, notably the Oneida Commune of John Humphrey Noyes:

Noyes also relates the Socialist movements which formed so many of the communes to the Revivalist movements which turned on the nation during the same period—these waves seem like the spiritual and social revolutions of nowadays, and the Secrets of Success seem to spring, then and now, from the commingling of the juices of these two aspects. There are differences, of course, between our communes and those of the last century—we inhabit the magical margins of the Surplus Society, while they were made up of Common People, who had to work hard for economic survival, though their toil was lessened by communal living.

from Kaliflower

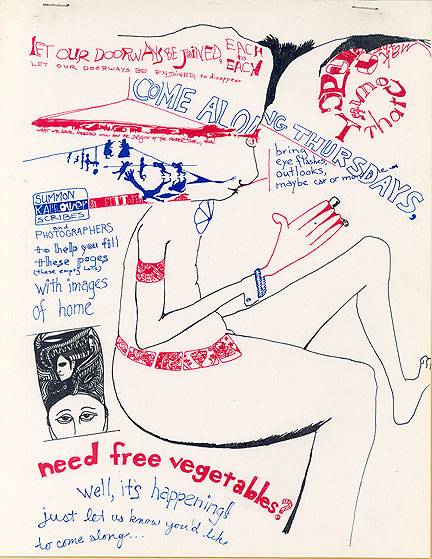

Those who lived in Kaliflower often cut ties to non-communalist friends and relatives, taking their communal brothers and sisters as their adopted new families. Chandler Downs, a former member of Kaliflower, said that attachment to a single sexual partner was frowned upon and most communards were polyamorous, sleeping in a group bed and regularly rotating sexual partners in what was loosely considered group marriage. When new members joined, they gave up their savings to the group and were encouraged not to take outside jobs, but to grow food in the communal garden or work in the Free Print Shop and help deliver the newsletter.

Kaliflower helped organize the Free Food Conspiracy in 1968 (later the Free Food Family), where participating communes pooled member food stamps and bought large volumes of food to distribute to each commune based on need. By 1973, 150 member communes participated in San Francisco.

from Kaliflower

The roots of Free that grounded the Diggers, Kaliflower, and numerous other communes sees its fruit in Food Not Bombs, the Really Really Free Markets, cooperative food systems, bicycle repair and tinkerer workshops, community gardens, and farmers’ markets. Also encouraging are the smaller communal exercises like Kaliflower and Black Bear, which both continue to operate despite the time that has passed, and have evolved to fit the needs of the changing cooperative landscape.

by Matthew Roth, from his essay "Coming Together: The Communal Option," in the anthology "Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78" (City Lights Foundation: 2011), edited by Chris Carlsson.

Find the book at City Lights!

Find the book at City Lights!