Kaliflower and the Dream Continues

Historical Essay

by Eric Noble, 1996

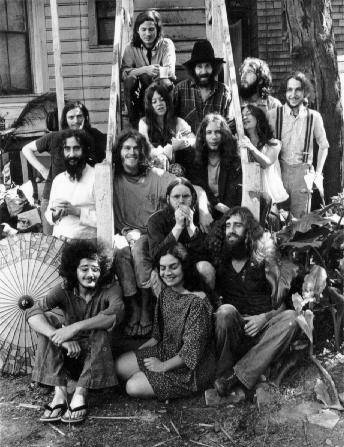

The Scott Street Commune gathered in the backyard of the Redevelopment-owned Victorian which they occupied from 1971 to 1974. The Free Print Shop was in the basement of the house next door. The Free Bakery would be located on the second floor next door after the Commune took possession of both buildings. This photograph was taken by Miriam, ca. mid-1972. Several members are absent.

Out of the spinning whirlwind of Digger energy flew sparks that caught fire in communes and communities all across CounterCultureLand. Groups in California, Oregon, Arizona, Wisconsin and elsewhere sprung to action starting in 1967 and took the Digger name in the way the Diggers had taken it from their English forebears. Others began Digger activities under different names: the Provos in Berkeley used the name of the Dutch group whose White Bike Plan had captured the imagination of anarchists everywhere.

Back in San Francisco, the original Diggers had dropped that name soon after their Death of Hippie parade/event/ritual. Then began the Free City cycle of activities before their final exit from the stage that the City streets had provided for the past two years. But by then a new Free community had sprung from the Digger legacy. Where the Mime Troupe had taken their art from the confined space of theaters into the parks, and where the Diggers had taken their energy from the parks into the streets, now there was a reversal of this trend. Free went indoors, back into the new spaces that were being created in the old Victorian homes and renovated warehouses of San Francisco. The glaring onslaught of media attention drove the movement underground again.

Hundreds of communes in the San Francisco Bay Area sprung up starting in 1967. One among them, variously known by the street where they lived (first Sutter then Scott and finally Shotwell), consciously adopted the Digger Free philosophy. The Digger ethic had permeated the counterculture—every commune invariably had a Free Box in the hallway, whole wheat bread was the staple foodstuff, and tie-dyed shirts were the fashion—but the Sutter Street Commune was bent on implementing the blueprint for action that the Digger Papers outlined a few months later.

Since the fifties, tales of Buddhist enlightenment had permeated the counterculture with the Beat poets' interest in Zen. One of the concepts that gained popular renown was the idea of "passing on the dharma." This was the idea of sacred teachings being passed from teacher to student. A passing of the dharma between the Diggers and the Sutter Street Commune took place in the early months of 1968. The commune's founding member brought his printing presses to San Francisco, inspired and helped by two of the Diggers to start the Free Print Shop. Just as the Communication Company had been inspired by the Diggers and set up shop to offer free printing services two years earlier, so the Sutter Street Commune announced their new service to the community.

This announcement of the opening of the Free Print Shop was printed on gold-lam paper, a trademark of the commune which had contacts with a large paper company in San Francisco and obtained odd lots of paper at bargain basement prices.

Over the next several years, the Free Print Shop published a variety of materials including flyers for other communal groups, free services, ecology groups, free arts groups, and the occasional political protest (albeit only if the artistic quality of the poster design passed certain muster.)

Kaliflower and The Free Print Shop

Logo of the Kaliflower Collective

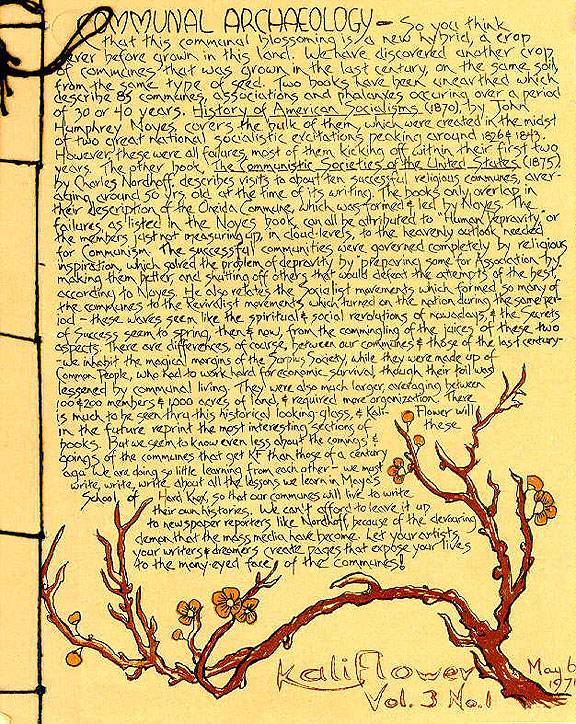

In the spring of 1969, the Sutter Street Commune began publishing an intercommunal newspaper. The name they gave this free weekly publication was Kaliflower, a play on Kaliyuga, the Hindu name for the last and most violent Age of Humankind, the idea being a "flower growing out of the ashes of this current age of destruction." For the next three-plus years, the commune, through the Free Print Shop, kept Kaliflower going. At its end, there were close to three hundred communes, mostly in the San Francisco Bay Area, that were receiving Kaliflower every Thursday. The progeny became so well known that eventually it gave its name to the parent, the "Kaliflower Commune" as many people called it.

In the beginning, each commune that received Kaliflower had a plywood board with a poster located in a communal space where the deliverers would hang the Kaliflowers. A bamboo tube, attached to the board, was where any free messages were deposited waiting for the deliverer to pick up.

"Kaliflower Day", as the name by which Thursdays became known, was an intercommunal ritual. That was the day of the week when Kaliflower got bound and distributed to all the other communes on the "routing list". Members from other households would show up at Sutter (later Scott) Street, and spend the morning binding the paper, using the Japanese sewing method which the Sutter Street Commune learned from their salvage stints in the old abandoned Victorian houses of San Francisco's Japantown and Western Addition districts (where they lived for the first seven years.)

Kaliflower became a valued channel of communication among these hundreds of communes. It was not unusual for people who delivered Kaliflower to come back with stories of going from one commune to another and being feted at each in various fashions. These messengers would pick up announcements and ads (always Free Ads) that would appear in the next week's issue. Since the basis of the Sutter Street Commune's vision was Digger Free, Kaliflower also became the vehicle that helped create a Free City among these communes.

Eventually someone, perhaps even myself, may write a detailed history of this period.