Seculovich's Lots in Mission and Bernal

Historical Essay

by Stephanie T. Hoppe

Stephanie T. Hoppe is a former staff counsel to the California Coastal Commission and a great-great-granddaughter of Peter Seculovich.

Part 5 of Peter T. Seculovich in San Francisco

The San Francisco Call and Post 1893.

During the initial discussions about the Kentucky Street embankment, Seculovich repeatedly petitioned for a drawbridge over Islais Creek, as was initially promised, but he is absent from newspaper reports about the subsequent dispute about the floodgate, perhaps in part because he was involved in disputes of his own. In 1876, he paid William Winter $250 for the southwesterly half—22 by 137 ½ feet—of a parcel that Winter owned on the Mission Bay side of Brannan Street halfway between Fifth and Sixth streets (subdivision 10 of South Beach Water Block No. 18). An 1861 survey shows the shoreline of Mission Bay angling from Townsend to Brannan streets, placing this parcel on dry land, but at the very edge of the bay, possibly on marshy ground. An 1869 survey shows buildings on both sides of this block of Brannan Street, but we do not know what structure was on Winter’s parcel. It was hardly a prime neighborhood, only a few blocks from the city dump on Berry Street and the then-location of Butchertown.

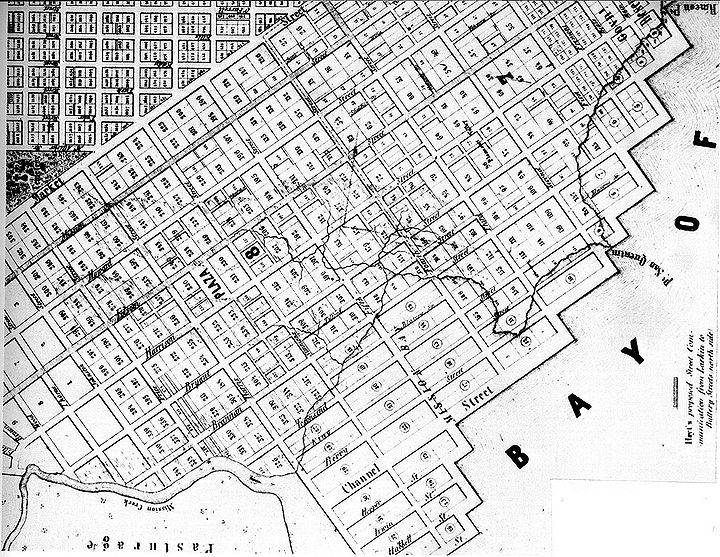

The plan for San Francisco in 1853. Zakreski’s map is entitled “The only correct & fully complete Map of San Francisco, Compiled from the Original Map & recent Surveys, Containing all the latest extensions & improvements, New streets, alleys, places, wharfs & Divisions of Wards. Respectfully dedicated to the City Authorities, 1853.”

Map: California Historical Society

Sometime later, Seculovich and Winter engaged an attorney, a former judge named James McCabe, to represent them in litigation concerning this property, and for his fee each agreed to grant McCabe one half of his ownership. Winter conveyed half of his half interest to McCabe, but Seculovich failed to do so. McCabe filed suit against him in August 1883, claiming Seculovich had committed fraud by conveying his interest in the property to his daughter and thus lacking title to transfer it to McCabe. McCabe also claimed that the property was worth $3,000—a considerable increase in the 6 or 7 years since Seculovich had bought a half interest for $250. If that valuation was not inflated, perhaps McCabe’s services had been worthwhile.

The judge dismissed the felony fraud charge, determining that although Seculovich did deed the property to Jennie, the deed had been left in escrow and conveyance was incomplete. McCabe then filed a civil suit for $9,000, charging Seculovich with fraudulent representation in the sale of real estate, and the following year, a second suit, this time for $2,650 worth of legal services. The following spring, McCabe had Seculovich arrested for perjury in a deposition. After “a long and tedious” examination, according to the newspaper report, the judge dismissed that complaint. Four months later the grand jury briefly took it up but took no action. That seems to have been an end to the matter, at least as far as the newspapers were concerned, leaving us in the dark about the outcome, as well as the specifics of the underlying case (Examiner, 8/8 and 9/2/1883, 8/22/1884, 4/29/1885, p. 3; Chronicle, 9/3 and 9/30/1883, 5/6, 5/19 and 9/19/1885).

Possibly Seculovich lost the property to McCabe, as it does not appear in any subsequent records or inventories of his holdings. Perhaps he was even required to pay McCabe additional money, as he seems to have been in a financial bind around this time. It is difficult to assess his financial situation at any time, but it seems always to have been somewhat precarious—and usually mysterious. In 1880, he applied for a position as watchman at the new city hall then under construction—perhaps simply because he frequented city offices and became aware of the opportunity. Also in 1880, he mortgaged two of his Precita Valley lots for $3,000. In 1882, he sold the Valley Street lot he had purchased for $100 in 1877 at a loss, receiving only $40 for it. In 1883, he conveyed 15 Bernal Rancho lots to his daughter, Jennie, then 13 years old, for love and affection and $250, according to the deed in surviving family papers. This deed was not recorded until February 1885, when he also sold 12 other Bernal Rancho lots to Louis Schoen for $600. Later that year he sold another Precita Valley property, for an unknown sum, to a William Bosworth and bought a different parcel from Bosworth a week later. In 1888, he paid Schoen $650 to repurchase 6 of the 12 lots he sold to Schoen three years earlier, and a week later sold one of them to a third party for $250. This property, present-day 156 Wool Street, remained undeveloped until 1912 according to Zillow.com and is now worth $1.6 million. In 1891, for $1, Jennie returned all the Bernal Rancho lots her father had conveyed to her. After 1885, his locksmith business no longer appears in city directories. After two years’ absence from the directories, in 1888 he was listed at his home address with his occupation reported as real estate.

He was not absent from the newspapers altogether, appearing in connection with issues in his neighborhood such as the widening of Mission Street near his home. As was common, the Board of Supervisors appointed a commission to set valuations of property to be taken and assessments for benefits received from the project. As was also common, residents protested, including a “V.” Seculovich, who opposed both the existence and the decisions of the commission “because he believed it to be acting in the interests of certain corporations and a few private individuals owning large tracts.” When the Street Committee of the Board of Supervisors upheld the street widening commission, Seculovich asked for $6,500 in compensation for the loss of a 16-foot strip along the 62-foot street frontage of his property, which was planted with fruit trees and rose bushes. The commission initially offered him $700, increased to $795, then $1,360. Ultimately, he received $2,000 (Examiner, 4/12/1889; Chronicle, 7/24, 9/17, 9/24, 12/10/1889).

Problems with the street work festered. In 1892, residents complained that the street was not yet paved and nearly impassible in winter and that further changes of grade—raising it five feet at Army and Twenty-Eighth streets, lowering it at Twenty-Ninth, which might affect Seculovich’s property—were needed for a proposed extension of the cable car tracks. They also objected to obstructions remaining in the widened roadway, apparently structures, including houses, located in the strip taken for the street widening and now owned by the city but not removed. Street lighting was another concern: “Changing the large masts for smaller ones, left the district in darkness in many places” (Chronicle, 1/22/1892).

According to a much later report, that summer Seculovich was injured in the collapse of an embankment at his home—possibly a result of the grade changes, which often left adjacent properties either buried or hanging above the new street grade. But as we have no record of the litigious Seculovich seeking damages, the injury was perhaps not severe (Call & Post, 1/11/1905, p. 16).

Seculovich favored another road project, joining with others to form the Howard Street Extension and Improvement Club to promote the extension of Howard Street (present-day South Van Ness Avenue) from Army Street to North Street (present-day Bocana Street) near Holly Park on Bernal Heights. By February 1891, the Howard Street proposal advanced to the point of the establishment of a commission:

A meeting of the Howard-street Extension Commissioners was held yesterday afternoon at ex-Judge Toohy’s office, and was attended by a large delegation of property-owners, who were anxious to receive a larger measure of damages than the appraisers thought fit….The only serious opposition to the extension came from Peter R. [sic] Seculovich, who appeared in person to support his protest against the work, which he attacked on every ground. The two principal contentions were that the commission was an entirely illegal body and could not legally carry out the work, and that the appraisers were unjust and partial in their valuations. These he stoutly maintained in a long-winded speech, bristling with legal points and reference to the Commissioners’ statistics, which eventually wound up with an appeal for $4000 instead of the $1845 allowed him, on getting which he promised to withdraw his opposition.

“In other words,” said Chairman McCoppin, “you think it perfectly just and legal for us to pay you over $4000, while you are quite positive we have no legal right to do so?”

“Certainly,” said the claimant, entirely oblivious to the loud guffaw which followed his answer, “the Mission-street Commission did it, and you and all the Commissioners do it right along.”

Under a cross-fire of questions it afterward came out that Seculovich’s lots are valued for taxation purposes at only $45 apiece, while their owner treasures them up at $1000 each, and does not want to part with them at that. He has six of them, of an irregular shape and only 55 to 75 feet in depth, situated on the apex of the hill, where the rambling goats most delight to congregate. He bought them thirty years ago, and has held on to them ever since on account of the splendid panorama to be seen from there, which he relied upon as a basis for the increased value of his property over that of his neighbors.

Mr. Seculovich is said to be the same gentleman who obstructed the widening of Mission street for a long time, and who obtained no little celebrity at the time by valuing cherry trees growing on his lot at $250 each, and every rose-bush and shrub at corresponding prices. He received but cold comfort yesterday from the commission, who consider the award in his case a fair one, and are perfectly willing, as they had no use for it, that he shall carry his panorama on to the remnant of his lots. (Call & Post, 2/10/1891)

Other efforts of the Howard Street Improvement Club met mixed results. The Board of Supervisors agreed to improve Holly Park, which contractors had been using as a quarry, but refused street lights. The club then asked for a police station and discussed the desirability of a cable car line on Howard Street. At an election for new officers, Seculovich was chosen sergeant at arms. The street extension commission finished its report in July and sent it to the Board of Supervisors, which held it over without ever accepting or rejecting it (Examiner, 8/27/1889; Chronicle, 4/19 and 7/30/1891; Call & Post, 7/30/1891).

The Howard Street extension proposal involved Seculovich personally in new litigation. He filed suit to quiet title to a lot adjacent to his six lots with “the splendid panorama.” In 1862, he stated, he “induced” Brown and Cobb, the lawyers from whom he bought his lots, to “convey a lot on Buena Vista Street, near Coso Avenue, to the infant son of Samuel P. and Margaret Morton, with the understanding that should the child die without issue they would reconvey the property to him.” He paid Brown and Cobb $10. The child died at the age of five years, but the Mortons failed to surrender the title to the property. We might assume that his suit also failed, as subsequent inventories of his properties do not include lot 568 (Call & Post, 2/19/1891).

Nor did the street extension come to fruition. Present-day South Van Ness ends, as Howard Street did then, at Cesar Chavez Street. His lots, and the Mortons’, remain undeveloped to this day. Located on the east side of present-day Bonview Street, 100 feet south of Coso Avenue, they lie in Bernal Heights Park.

On other neighborhood issues, Seculovich met with more success, obtaining, for example, an order from the Health and Police Committee of the Board of Supervisors for removal of a noxious tannery. When “a respectable number of taxpayers, who own property on Mission street, between Twenty-sixth street and Cortland avenue, and adjacent streets and avenues,” met to organize the Mission Street and Precita Valley Improvement Club,” he was elected president. A stockyard at the corner of Fair Avenue and Mission Street, next door to Seculovich’s home, received special attention from the club, which voted “to assist the authorities in having it removed at once.” A few weeks later, the club met at Seculovich’s home to discuss three tanneries continuing operation despite orders of Board of Health. Stockyards also came up, both the one located next door to Seculovich and another on Cortland Avenue, said to be keeping more than two cows in violation of the city ordinance (Call & Post, 2/22, 3/8 and 3/28/1893).

New construction on Mission Street to install an electric-car line put many property owners to considerable expense “as the grades furnished the railroad company are at variance with those established for many years, and to which the sewers have been laid and the street improvements made.” The club appointed Seculovich to lead a committee to complain to the Board of Supervisors and mayor about broken-down wagons obstructing the roadway as well as the tanneries, stockyards and a glove factory condemned years before but remaining active (Call & Post, 4/4, 5/4 and 6/15/1893). The Call & Post took up the “cow pen” next door to Seculovich at the corner of Fair Avenue and Mission Street in a lengthy article illustrated with an artist’s sketch of the pen with Seculovich’s house and tree-filled yard visible above the fence in the background:

The large space is divided into corrals, and partially occupied by rickety sheds, while forlorn cows and distressed-looking horses wander about the little spaces. Goats scramble over the fences and join in the general search for something to eat.

There are great piles of manure in the enclosures, and the contracted stalls are damp and odorous. In one of the small stables there were four cows crowded, while others ambled about the lot. The horses were confined in the lot that corners on Fair and California avenues, but the cows are directly on the Mission street front, nearly opposite the turn-table of the Valencia-street cable road.

In spite of the unhealthful surroundings Mr. Salomon denies that the place is a nuisance, though he confesses that he has been arrested on such a charge. “It is all spitework,” he said, “and is caused by this man Seculovich, who lives right next my cow stables.”

An inspection of the premises of Mr. Seculovich showed that the rear end of Salomon’s cow stables was within a few feet of his kitchen door, and the stench of the offal was almost unendurable. Seculovich has a comfortable though unpretentious home, and his yard is filled with flowers and fruit trees. He says that the odor from the adjoining cowshed has caused him no end of annoyance and that he proposes to insist upon the abatement of the nuisance.

“The law very plainly prescribes that no person is permitted to maintain more than two cows within the city limits,” said Dr. Keeney, the head of the Board of Health, although he admitted the laws contained ambiguity and exceptions. He added that the slope of this property

is a particularly bad feature. It drains directly into Mission street and befouls the cellars and yards on the lower side of the street. On damp, foggy days the stench of the stockyards clings closely to the ground, and the breezes carry it directly into the houses, to say nothing of offending the nostrils of every person within a radius of a mile or more.

The stockyard proprietor’s son told the reporter, “We only keep cows here occasionally. We buy and sell and the stock is never here more than a day or two at a time.” “But then you get fresh stock in its place, don’t you?” “Oh, yes, that’s our business. We buy and sell and use this yard as a place of inspection for purchasers. Our place is no worse than lots of others, and I am going to fight the law in Superior Court” (Call & Post, 7/29/1893).

That fall, the Mission Street and Precita Valley Improvement Club presented Seculovich with a gold-headed cane in recognition of his services as officer. The following year, with paving under way on Mission Street between Army and Thirtieth streets, club members met again at Seculovich’s home, determined to refuse to pay assessment for the paving because it was not being done as required. The club also advised its members to construct sidewalks with “artificial stone,” which would prove more durable than less costly alternatives. The controversy over the paving continued a year later with Seculovich, as president of the club, filing “a long protest” with the Board of Supervisors. In 1896, Seculovich asked for a park at Valencia and Mission streets, near his home (Call & Post, 11/29/1893, p. 8, 8/19/1894, 7/24/1896; Examiner, 6/30/1895).

All sources for this 10-part article appear at end of Part 10.