Long Bridge Becomes Kentucky Street

Historical Essay

by Stephanie T. Hoppe

Stephanie T. Hoppe is a former staff counsel to the California Coastal Commission and a great-great-granddaughter of Peter Seculovich.

Part 4 of Peter T. Seculovich in San Francisco

Preparations for grading Kentucky Street continued, together with protests against it. The Board of Supervisors overruled all the objections, and over the summer of 1886 collected $175,000 of the estimated cost of $199,000. The sheriff prepared to sell delinquent properties to collect the remainder. “No part of the city is so well suited for development,” the newspapers enthused. “The hills will “settle up,” and the “Mission and Islais Creek mudflats will become things of the past” (Chronicle, 6/16/1886, p. 2; Examiner, 7/26/1886).

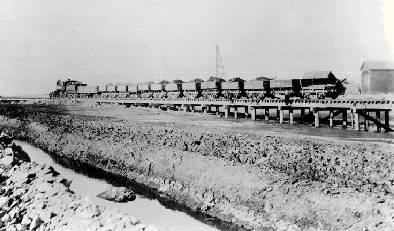

The term “grading” seems more than usually inadequate applied to this project. The first phase required creating a roadbed 80 feet wide for a distance of nearly 2,000 feet across the open waters of Mission Bay, “through water of varying depth and through mud which varied still more.” To accomplish this, the contractor excavated 500,000 cubic yards of rock from Potrero Hill, “a kind of soapstone, which requires blasting to loosen it, but which slacks and crumbles on exposure to the air and to water” and was said to make an “excellent roadbed” and “if kept sprinkled will be one of the smoothest and cleanest drives in the city, but without sprinkling it will beat up into an almost impalpable dust in summer, and will be a quagmire of mud in winter if a long period of wet weather should set in.” Macadamizing, which would cost another $50,000, was not included. The contractor finished on time in one year (Chronicle, 12/5/1886).

Around 1903, the Santa Fe Railroad removed a great portion of Potrero Hill. The portion removed came from the areas of Iowa Street extending east and then south to the area of twenty-second and Missouri. The dirt and rock were used to fill the marshland between Iowa Street and Massachusetts...The Southern Pacific Railroad similarly received a state grant to fill in Mission Bay. For twenty years, the bay was used as a dumping ground.

Photo: California Historical Society, San Francisco, CA

The second, more extensive, section, crossing some 4,400 feet of open water at the mouth of Islais Bay, was estimated to require 1 million cubic yards of fill but also to be completed within a year’s time. Two trains of 19 cars, loaded by steam shovels, ran on trestles adjacent to the Long Bridge, the cars tilting to dump their contents on one side or the other. With day and night shifts, the workers filled and emptied 100-250 carloads per day. Problems soon arose on the Long Bridge:

The mud at the bottom is said to be almost thirty feet in depth, and the large mass of rock already thrown in has pushed up the mud against the piles in such volume that many of them have split, and the bridge itself in many places leans far over on the other side. (Chronicle, 9/22/1886, p. 3)

With the gas mains running on the bridge threatened, the gas company shut off supply to a large number of residents and businesses. The resulting loss of street lights made for hazardous travel at night, with old and broken railroad ties sticking up here and there and holes “big enough to break a man’s neck if he were to step into one unaware.” Hauling with teams by night ceased altogether.

The alternative route via Fifteenth Avenue and the San Bruno road into the Mission is “a quagmire during the winter” (Chronicle, 12/5/1886, p. 8).

Evidencing the magnitude of water that flowed with the tides in and out of Islais Creek, a few months into the work the contractor asked permission to put in an 80-foot-wide masonry culvert on a pile foundation across the creek, as the wooden culvert already built “has been found to be entirely inadequate” (Examiner, 5/24/1887, p. 3). Accompanying the tons of fill came “occasional collapse and disappearance of large areas of earthwork.” A reporter inspecting the work noted

the effects produced by the pressure of the earthwork on the slippery foundation. On each side of the road we found the mud displaced to such an extent that in some places the ridges formed had risen almost to a level with the new formation. The appearance is as if a tidal wave of mud had approached the road on either side and remained stationary after receding a few feet… on one occasion the embankment subsided eight feet in a few minutes, leaving a gap of 800 feet to be refilled. (Chronicle, 8/11/1887)

The Butchertown slaughterhouses that abutted on the Long Bridge had their pile foundations forced several feet out of perpendicular. Saloons and workshops fronting on the new roadway watched the “wedged out mud” encroaching and loosening and lifting the piles on which their premises were built. “On Friday night last Belgard’s French hotel after a couple of preliminary heaves slid off its foundation on to the mud flat behind.” The adjoining blacksmith shop “followed suit, and a paint shop some yards away also succumbed.” But the sympathies of the property holders stayed with the contractors, wishing the project to come to a successful conclusion (Chronicle, 8/11/1887).

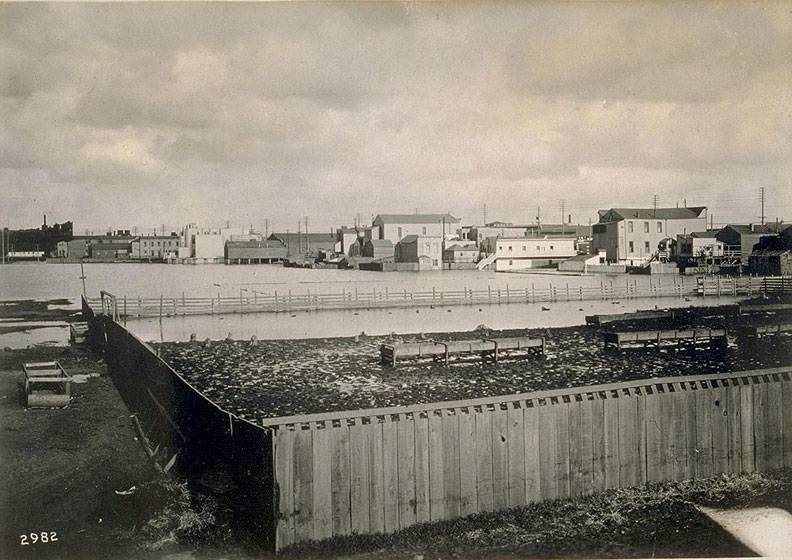

Butchertown along the shore, early 20th century.

Photo: Online Archive of California

In December, the contractor requested and was given a 90-day extension to complete the work. The cost coming to more than expected, the contractor then declared bankruptcy, but the work continued (Examiner, 12/9/1887, 1/18/1888, p. 2). When the winter rains began, residents saw the effects of the embankment on the marsh around Islais Creek:

A Mass of Filth. San Bruno Road Infected by a Nuisance. The property owners on the San Bruno road have sent a petition to the Board of Supervisors calling that body’s attention to the outrageous and unhealthy condition of their neighborhood since the filling in of Kentucky street. The petitioners allege that there is not sufficient outlet for the waters of Islais creek and the sewerage and surface water from the surrounding country that empties into it. As a consequence, the petitioners say, the late rains have filled up the large basin formed by Kentucky street, the San Bruno road and the hills on either side. It has become a large lake into which is constantly poured large volumes of water and sewerage from the Army-street sewer and the surface draining for miles around. To this is added the refuse and filth from the tanneries, soap factories, glue factories and the Smallpox Hospital. It is asked that a culvert shall be cut through Kentucky-street bulkhead in order that the putrid lake may be drained into the bay. (Chronicle, 2/2/1888, p. 8)

The Street Committee directed the Superintendent of Streets to notify the contractor to keep the culvert open and take whatever other steps necessary to prevent water backing up (Examiner, 2/10/1888, p. 6).

In April, the “grading” was completed, a distance of nearly two miles across Mission Bay and Islais Bay. Shortly thereafter, at their own initiative and expense, some nearby landowners installed a floodgate in the culvert draining Islais Creek and Bay, which immediately caused problems for residents farther upstream. The Potrero Avenue Improvement Club objected that “the salt water is prevented from going up with the tide and flushing the Army-street and Pesthouse sewers. As it is now, these empty on dry ground, to the manifest injury of the health of the neighborhood.” The Board of Supervisors instructed the Superintendent of Streets to remove the floodgate. The landowners who installed the floodgate claimed it beneficially “reclaimed”—that is, dried out—"the vast body of unwholesome marsh and overflowed land in that vicinity, and thus making it available for business and residence purposes.” They argued that the city could properly have been called upon to install the floodgate, and if the city now removed it and their property was again overflowed, the city would be liable for damages: “The city cannot with impunity permit property to be overflowed, either by a sewer or because of the absence of a sewer” (Chronicle, 4/17, and 7/13/1888; Examiner, 7/17/1888).

The dispute dragged on. The city attorney advised that individuals lacked authority to construct floodgates, but the city surveyor favored maintaining the floodgate. The health officer was of two minds: With the floodgate closed, the Army Street sewer emptied on the flat; if opened, Butchertown offal came in with the tide. Best to build a better sewer.

Some argued the underlying purpose of the floodgate was to entirely fill and obliterate Islais creek. Others scented opportunity, advertising for sale 20 marsh lots in Bernal Rancho, 25 by 70 feet, that “will soon be valuable property.” The Board of Supervisors asked who owned the tidelands affected by the floodgate: the city, the state, or private persons—a question without a straightforward answer due to divergences between Mexican and American law as to whether property ran to the midline of the waterway or to the line of high (or low) tide. Those who believed the floodgate was “part of some land-grabbing scheme” might have seen confirmation in the decision of the Board of Supervisors to reconsider its resolution calling for the opening of the floodgate. Petitions flowed for and against the floodgate, but in the end, the board rescinded its order to remove the gate (Examiner, 9/21, 9/30 and 10/3/1888; Chronicle, 11/10 and 11/27/1888).

Probably not coincidentally, that winter the state legislature considered new measures for “reclaiming” swamp and overflowed lands. Proponents argued the Kentucky Street grading illustrated the shortcomings of existing law that only allowed individual parcels to undertake reclamation: the contractor lost $27,000 in place of the expected profit of $43,000. Joint action was required. Installation of a seawall across the mouth of Islais Bay, dredging on the outside and filling on the land side could convert some 2,000 water lots owned by 700 persons into solid ground usable for commercial purposes, and Islais Creek could become “the best part of San Francisco’s water front.” Filling the marsh would remove the noxious odors from Butchertown offal in the water. Over the protests of “citizens of Islais creek and Butchertown flats,” the bill passed. A proposal followed to reclaim 227 acres of Islais marsh, including the area of Butchertown and its associated tanneries. As the butchers favored the proposal, suspicion arose that they actually intended to preempt and preclude reclamation rather than institute it (Chronicle, 2/3 and 2/27/1889; 2/5 and 4/24/1889, p. 5).

Issues remained with the Kentucky Street embankment itself, with calls for the roadway to be macadamized and curbed: “The streets have been graded after a fashion, but have been left in an impassible condition.” The Examiner called the slaughterhouses “a blight on property in the New Potrero and on the southern edge of Bernal Hights”:

In a large district around Islais creek is daily scattered large quantities of refuse matter with its noisome smells. Much of the offal floats down the creek, and is scattered broadcast along the shores of the bay. The Oakland side gets very much of this unwelcome matter, and the water front of this city is affected by it.

The Examiner recommended moving the industry to the far southwestern corner of the city, close to an ocean outfall for waste, from which railroad delivery into the city “would do away with the unsightly wagons that with six and seven horses come into the city a dozen times a day covered with mud from the marshes of Islais creek” (Examiner, 4/12 and 6/9/1889; Chronicle, 5/17/1889).

Nor was the floodgate issue resolved. More than a year after it was installed, the Health and Police Committee of the Board of Supervisors directed the Superintendent of Streets to “take immediate steps to open the floodgate.” The San Bruno Road Improvement Club pointed out that at present, perhaps due to the winter rains, “the water in Islais Creek was clear, and that by removing the floodgates it would always remain so and carry off all the sewage from Army street, the Pesthouse and the vicinity.” At another meeting of this club, which seems to have been John Reynolds’s alternative to the Islais Creek Property Owners Association dominated by Seculovich, Reynolds “dwelt on the advantage to be derived from the opening of Islais Creek, and said that whenever a canal opening the creek for navigation should be built many of the industries now carried on across the bay will be transferred to this county” (Examiner, 10/19 and 12/23/1889; Chronicle, 2/17/1890).

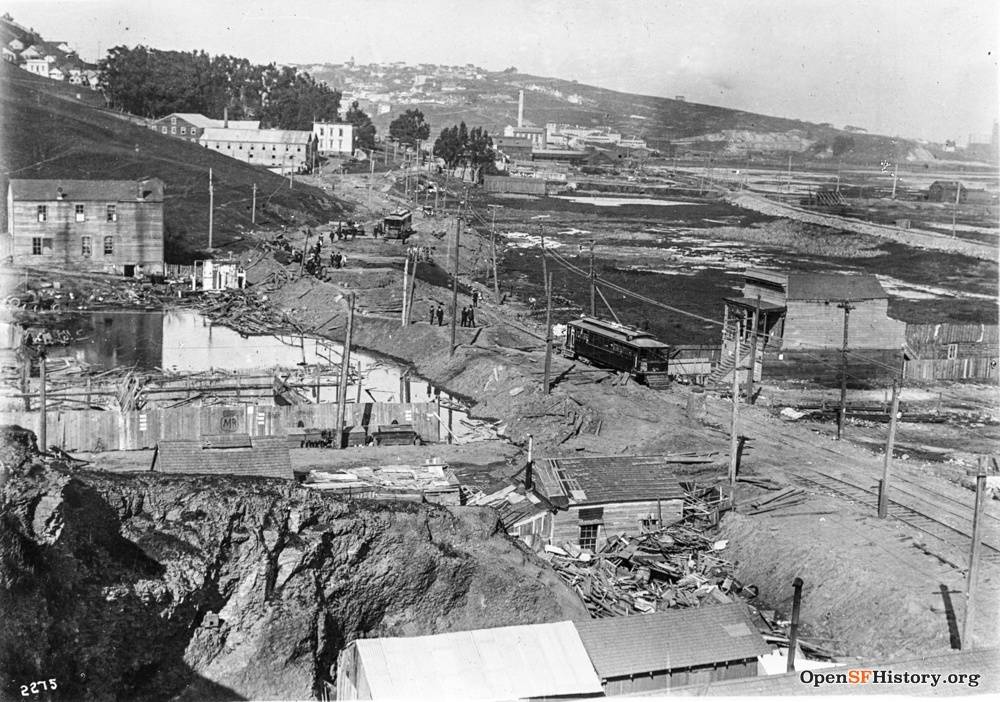

San Bruno and Cortland Ave., 1915, looking north with Bernal Heights rising to the immediate left and Potrero Hill in the distance. Islais Creek wetlands occupy today's Bayshore Blvd. industrial zone. These wetlands also drained Precita Creek, which ran down beneath Army Street on the north side of Bernal Heights. The old H streetcar is visible running along San Bruno Avenue just east of Bernal Hill, just west and above the still un-"developed" wetlands of Islais Creek.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp36.00732.jpg; DPW Book 11 DPW 2275

All sources for this 10-part article appear at end of Part 10.