Willie Mays: A Tribute

Historical Essay

by Howard Isaac Williams

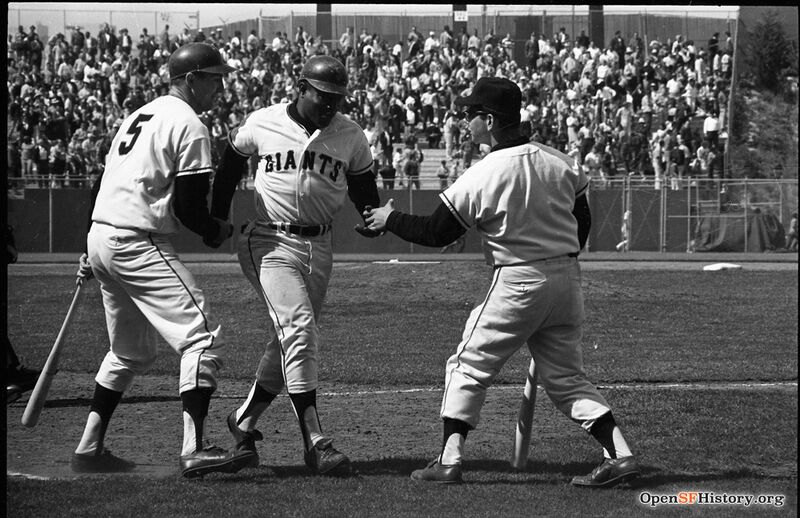

Willie Mays crossing home after a home run at Candlestick Park, c 1964.

Photo: OpenSFhistory.org wnp14.6478

Willie Mays was one of the greatest baseball players of all time. Many who appreciate the game call him the greatest.

Every Giants fan from New York and San Francisco who enjoyed the game in the 1950s and 60s has vivid memories of Mays delivering a clutch hit, making a leaping catch or throwing out a baserunner from deep in the outfield.

Or making a daring dash along the base paths.

One of the most difficult plays in baseball is to score from first base on a single. A fan is far more likely to see a batter swat a pitch 400 feet than to see a runner successfully dash 270 feet from first to home on a one base hit.

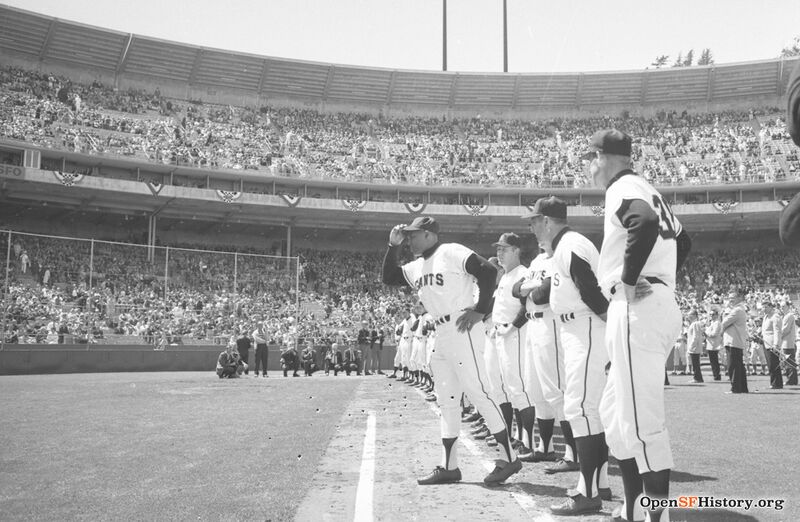

San Francisco Giants opening day, 1966. Willie Mays steps forward as he's introduced to the cheering crowd.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp28.6189

Near the finish of the 1966 season, the Giants were battling the Los Angeles Dodgers for the National League pennant. It would become another illustrious chapter in what many consider America’s paramount sports rivalry. That heritage had started in New York City when the Giants played in Manhattan and the Dodgers in Brooklyn. By 1958, when both teams decamped from the Big Apple and moved west—the Giants to San Francisco and the Dodgers to Los Angeles—their legendary rivalry had already transformed baseball and America. In 1947, in the first great postwar triumph of the Civil Rights Movement, the Dodgers had broken baseball’s color line when Jackie Robinson joined them. The Giants quickly signed Black ballplayers and by 1949, both teams had become the first National League teams with two Black players on the field. America’s first nationally televised baseball game was the third and deciding game of the 1951 National League playoff series between the two teams. The entire season that had seen the Giants whittle down the Dodgers 13 1/2 game lead in mid August to a tie at the end of regular play came down to the last of the 9th inning with Brooklyn leading 4 to 2. With two Giants on base, Dodger pitcher Ralph Branca faced the Giants’ Bobby Thomson at the plate. Twenty year old rookie Willie Mays waited on deck.

Even if you know what happened next, here is the clip of Russ Hodges announcing the incredible conclusion to the game:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/WWIGfBQghJs?si=I-TPGax_rdyiJfl9" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" allowfullscreen></iframe>

(One “person” who never found out what happened next was Sonny Corleone. That was the ballgame that Sonny was listening to on his car radio when he was gunned down at the toll booth in The Godfather.)

After the two teams moved west, their historic rivalry intensified in the 1960s as one or both teams were in every pennant race from 1961 to 1966. In 1965, their fight for the pennant became a literal one on August 22 when the two teams brawled at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. Both teams’ dugouts emptied after Dodger catcher Johnny Roseboro was injured when Juan Marichal of the Giants struck him with a bat. Willie Mays quickly intervened to save Roseboro from more serious injury and halt the brawl. Although Marichal was suspended and fined, Roseboro had charged at him with his catcher’s mask. Before Marichal retired in 1975, he and Roseboro reconciled.

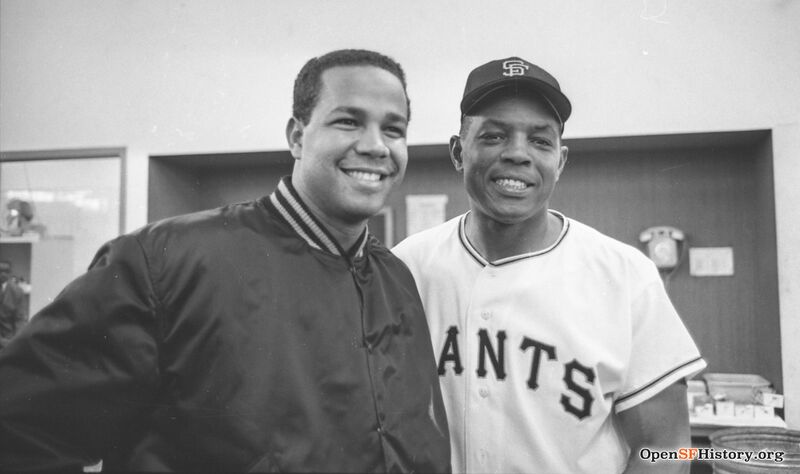

After an opening day win in 1966 over the Cubs—Mays homered and Marichal pitched a complete game 3-hitter at Candlestick Park.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp14.2503

In September 1966, the two teams were again in a close race for the National League title when the Giants came to Los Angeles for a three game series. The teams split the first two games.

The third game was played at night on September 7. At the end of the 9th, the score was 2-2, forcing the game into extra innings. The 10th and 11th innings passed without any scoring and at the top of the 12th the first two Giant batters were retired. But then Willie Mays came to the plate and singled. Now rookie Frank Johnson stood at bat. The 23 year old outfielder had just been called up from the minor leagues and was playing in his first major league game. He had been hitless in his first at bat. Sixty feet and six inches away on the pitcher’s mound stood Dodger reliever Joe Moeller. Mays took a safe leadoff from first. At the relatively “old” age of 35 and with two outs, he was not a threat to steal. He had slowed down a step or two but had compensated with a daring born of experience yet tempered by the shrewd judgement developed during his amazing career.

In the announcer’s booth was Russ Hodges, the same man who had broadcast Thomson’s historic home run in 1951. Like all Giants games played in Los Angeles, this one was televised throughout most of Northern California. Games on TV allow the announcer to choose which camera to broadcast the game’s action. Announcers usually direct the cameras to “follow the ball,” showing the pitcher throw to the batter and then following the ball’s course after it’s hit. But good announcers sometimes improvise.

With two outs, Mays would take off if Johnson’s bat made any contact with the pitch.

Moeller threw and Johnson cracked a single into right field.

Up in the broadcasters booth, Hodges directed the camera crew: “Let’s watch Mays!”

In barely an instant longer than it took to say that, Mays had darted along the 60 yards between first and third bases. The camera showed him round third and look toward right field. Home plate lay about 30 yards away.

"He may try it!" Hodges exclaimed.

Mays hesitated, then took off.

“He’s gonna try it!”

The throw from right field was perfect. Catcher Johnny Roseboro made a sweeping tag as Mays slid into home. The umpire’s right hand came down hard and fast like a judge’s gavel.

“He’s out,” Hodges said.

But Mays jumped up and pointed at the ground. The ball was rolling away ! Coming at the end of his 90 yard sprint from first base, Mays’ power slide had knocked the ball away from one of the game’s best defensive catchers. The umpire changed his mind and quickly waved both arms wide.

“He’s safe! The Giants lead!”

And the Giants went on to hold their lead in the bottom of the 12th to beat the Dodgers 3 to 2.

The greats make others better. On that night in Los Angeles, Willie Mays had shown us a measure of his greatness but had also given young Frank Johnson a chance to make his first major league hit a game winning one. He had given the veteran sports announcer Russ Hodges a chance to use his broadcast skills to showcase the Hall of Fame player’s base running virtuosity.

And the greats can even make their opponents better. Although the Dodgers lost that game, they bounced back to win the pennant on the last day of the season, finishing a scant 1 1/2 games ahead of the Giants.