Strip-Club Business: A Brief History

Historical Essay

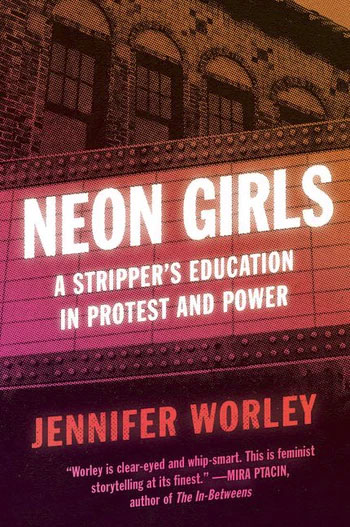

by Jennifer Worley, excerpted from Neon Girls: A Stripper's Education in Protest and Power] HarperCollins Books: 2020, a first-hand account of the epic union organizing campaign at the Lusty Lady Club in North Beach.

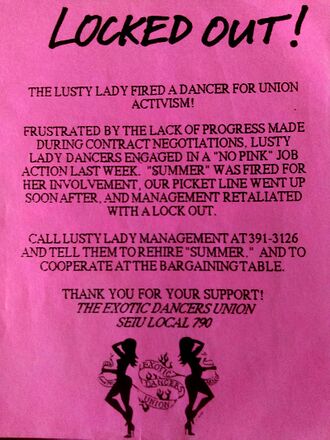

"Just Cause" flyer during the Lusty Lady campaign, 1997.

courtesy Jennifer Worley

Before the 1980s, strip clubs provided no-contact sexual entertainment for the most part. Then, the cops shut down all the city’s massage parlors and “encounter studios” (1970s-era brothels). After that, the strip clubs tried to fill the vacuum by pressuring dancers to provide full or partial contact sexual services. Club owners started by dropping dancers’ pay down to minimum wage so they would have to hustle for tips to make money. In 1980, the Mitchell Brothers O’Farrell Theatre introduced lap dancing, in which dancers would gyrate on high-tipping customers’ laps. Some Mitchell Brothers dancers began making hundreds of dollars each night.

In 1988, Mitchell Brothers changed the status of its strippers from employees to independent contractors so that management didn’t have to pay them a wage; the logic was that the dancers were selling services directly to the customers, with the club acting merely as a venue in which they operated their various “independent businesses.” Soon after, the club began charging dancers a booking fee or stage fee of ten dollars for each shift. In the early 1990s, other theaters began following suit.

The negative impact of this move for dancers reached far beyond the minor expense of the booking fee. Because clubs were no longer paying dancers for their time, management began scheduling as many dancers as possible, even on nights when business was too slow to support that many workers.

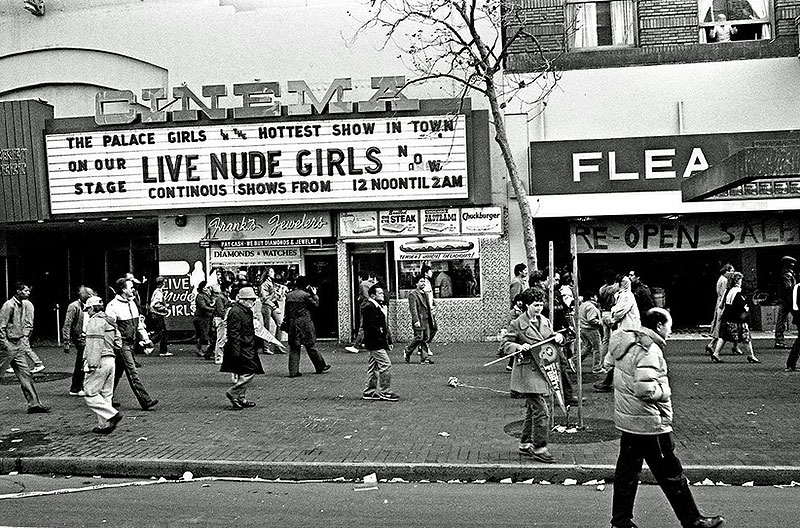

Market Street Cinema between 6th and 7th Streets on the south side of Market Street in the mid-1980s.

Photo: Dave Glass

Daisy explained that when she’d first worked at Market Street Cinemas, there would be maybe ten dancers on a shift. So say on a given day, if customers spent a total of $3000 in tips, dancers would average $300 for the shift. Yeah, some would make $600 and some would make $200, but everyone could walk out with enough to pay their rent. But after the clubs started charging a booking fee, management had an incentive to book as many dancers as they could. Sometimes there would be thirty or more dancers per shift, but the number of customers remained constant. That meant all thirty dancers had to compete for that same $3000, so the average amount per dancer went down to $100 per shift, and plenty of girls left with nothing. Others started offering hand jobs or more in order to compete. But management didn’t care, because they were making their money off the dancers, not off the customers.

So in 1993, Dawn, Johanna, and Daisy got together and formed [[|Exotic Dancers Alliance. They filed a complaint with the Labor Commission against the Market Street Cinema and won. But after the decision, the club owners doubled the stage fee and tried to turn the remaining dancers against EDA by blaming the lawsuit for the increase, saying EDA forced management to spend huge sums on legal fees.

Johanna explained that when she was dancing at Mitchell Brothers, management just kept raising the dancers’ booking fee higher and higher, so five hundred current and former dancers had organized to file a class-action lawsuit to recoup past booking fees and unpaid wages (since the club didn’t even pay the dancers minimum wage).

The Longer History of Sex Worker Organizing

As I began researching the history of the sex-workers’ rights movement, I learned that in the 1930s, it was common for strippers to be involved in performers’ unions that included burlesque comics, musicians, nightclub singers, and “respectable” stage actors. The most famous among these stripper-organizers was Gypsy Rose Lee, an extremely active member of the labor movement: she spoke frequently at union meetings in support of workers’ struggles, attended meetings of the Communist United Front, and was blacklisted in Hollywood during the Red Scare perpetrated by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee. Her novel The G-String Murders actually includes a character who is both a stripper and the shop steward for the union representing performers at the famed Minsky’s Burlesque in Times Square in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

The unionized strippers of the burlesque era began to disappear in the 1950s, as burlesque fell out of popularity, and striptease moved from theater venues like Minsky’s to bars and nightclubs. As alcohol sales replaced ticket sales as the venues’ key source of revenue, dancers began making their money by hustling drinks: customers would buy dancers drinks in exchange for their company at the bar or a table, and clubs began paying each dancer a kickback on the amount her admirers spent while in her company. Unbeknownst to the customers, who paid full price for the ladies’ cocktails, bartenders often omitted the alcohol from the dancers’ drinks, both to make the whole hustle more profitable for the bar, and to allow the dancer to stay sober for a night’s work, during which admirers might buy her dozens of drinks.

Just as stage fees and independent contractor status were ruining stripping for many dancers in the 1990s, the drink hustling of the 1960s replaced the flat-rate salaries, work rules, transparent pay scales, and other practices previously achieved by union contracts. Moreover, the shift of the worksite from the stage to the barstool erased stripping itself as a form of labor, since workers made their real money hustling drinks, not performing. Finally, rather than encouraging performers to fight collectively for better working conditions and wages (as they had during the burlesque period), the commission system pitted dancers against each other. Strippers competed with each other for the attention of big-spending customers by showing more and more skin, eventually flashing their nipples and pubic areas in order to sell more drinks after their show.

The effort to one-up other performers with a sexier act, more outrageous staging, or more elaborate costumes gave way to an outright race to the figurative and literal bottom in the 1950s, as the clubs and dancers competed to show more and more skin. As nudity began to trump creativity, and burlesque theaters fell out of fashion in favor of nightclubs, the status of strippers changed. No longer viewed as skilled performers like musicians or comedians, in the ’50s strippers were gradually excluded from performing artists’ unions. Around the same time, general union membership began its precipitous drop from over 30 percent of the American workforce in the early 1950s to today’s 11 percent. All these factors—the demise of burlesque, the rise of drink-hustling as striptease moved to nightclubs, and the overall drop in union membership among the American workforce—led to the total disappearance of unionized strippers by the early 1960s. By the time the Lusty Ladies began our organizing campaign, even the memory that strippers had ever previously unionized had been all but erased, so that we were often hailed as the first unionized strippers.

Still, during the 1960s and 1970s, other sex workers continued to organize. One of the earliest acts of collective protest by sex workers occurred in San Francisco in August 1966, when a group of transgender sex workers, fed up with continual harassment from police and security guards, rioted at Compton’s Cafeteria in the Tenderloin District, then the city’s main gay neighborhood. A month after those riots, a group of mostly gay male youth called Vanguard, many of them hustlers, demonstrated against police sweeps targeting sex workers and other people involved in the underground economy of the street. Similarly, the New York City group Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries sought to empower transgender sex workers. While generally associated with the rise of the gay liberation movement, these groups might also be seen as some of the earliest organizations in the nascent sex-workers’ rights movement.

In the early 1970s, the women working at the American Massage Parlor in Ann Arbor, Michigan, went on strike, protesting their treatment by the parlor’s owner, who had reconfigured their working hours without their consent. They picketed in front of the massage parlor during the strike, hired a lawyer, and filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board, which held a hearing over their wage and hour complaints. They ultimately won a settlement from the massage parlor and went on to organize a local decriminalization drive, in the service of which they created PEP (Prostitution Education Project) to educate other lesbian-feminists about sex-workers’ issues.

And the same thing was happening overseas as well. On June 2, 1975, one hundred sex workers occupied St. Nizier Church in Lyon, France, to protest the prison sentences that ten of them had received, as well as the failure of police to investigate the recent grisly murders of three local sex workers. This occupation triggered solidarity occupations around the world, including in Paris (where Simone de Beauvoir visited the occupiers), and San Francisco, where a solidarity strike was called by an emergent sex-workers’ rights group named COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics).

Founded in 1973 by ex-beatnik Margo St. James and sociologist Priscilla Alexander, COYOTE sought to end the stigmatization of prostitutes and pushed for the inclusion of prostitutes’ voices in the burgeoning women’s movement. In the 1970s, COYOTE succeeded in abolishing mandatory STD testing, and the practice of jailing women arrested on prostitution charges under the guise of quarantining them to prevent the spread of STDs, and even temporarily halted the prosecution of those arrested for prostitution. Members of COYOTE had mentored and helped organize the young dancers who formed EDA in the early 1990s, the same dancers who had, in turn, helped us begin our own organizing effort.

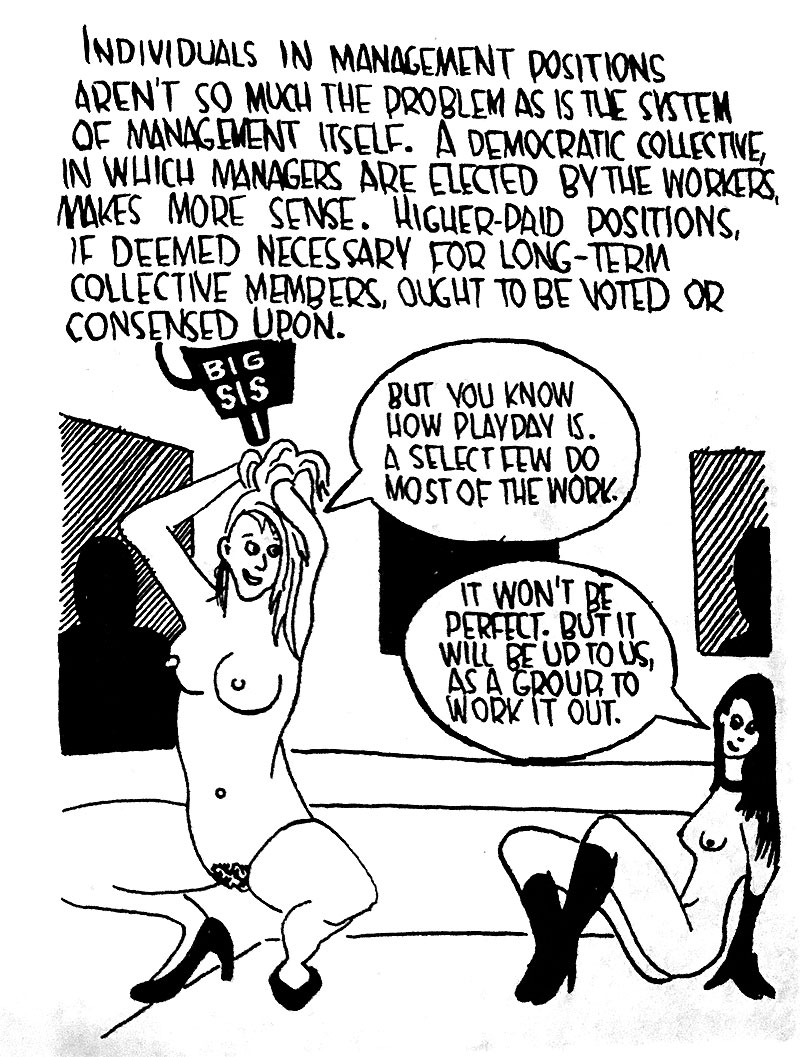

from the 'zine, "Playday Everyday!" Anarchy at the Lusty Lady" by Michael Ulrich

by Jennifer Worley, excerpted from Neon Girls: A Stripper's Education in Protest and Power HarperCollins Books: 2020, a first-hand account of the epic union organizing campaign at the Lusty Lady Club in North Beach.