Segregated and Substandard Housing in the 1920s

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "Progressive Era Housing Reform," Chapter One of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

North on Bartlett Street from 24th Street, January 1926.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0050793A

Without more government legislation, San Francisco’s housing and neighborhoods during the 1920s reflected household income, racial discrimination, and the decisions of property owners. Some San Francisco homes rivaled the best urban housing in the world—elaborate and spacious Victorians with private gardens and ritzy mansions sporting spectacular views. But the city’s worst dwellings were on par with the worst dwellings in the nation—dark, dangerous units without running water or bathrooms. Chinatown and North Beach had some of the most deficient housing, including the legendary subterranean units disparaged by the press and housing reformers. In the Western Addition and Mission districts, row houses and Victorians by and large survived the earthquake and fires. After 1906, when demand for housing soared, many property owners subdivided their homes or replaced them with apartments, and housing quality often diminished with higher population densities and reduced upkeep by landlords. Of the two working-class districts, the Mission had a higher rate of homeownership, but often what appeared as well-kept homes had crumbling and unhealthy interiors. San Francisco then, like today, was a city of renters who in some districts outnumbered homeowners nine to one.(43)

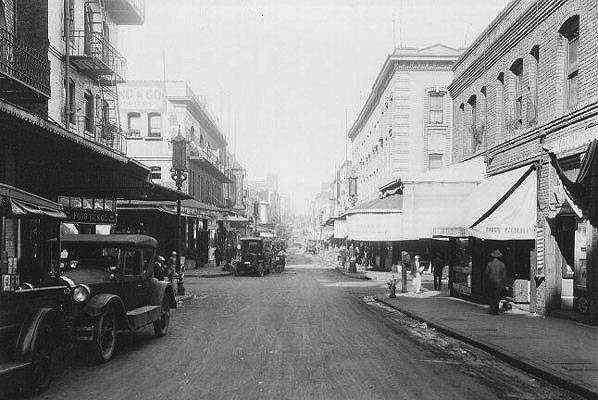

Mission Street east side between 23rd and 24th Streets, September 1926.

Photo: Jesse Brown Cook collection, online archive of California I0051287A

San Francisco’s districts also reflected the cultures and circumstances of the many ethnic groups that populated them, from the Western Addition to Chinatown, and growing racial segregation. Although black residents were not limited to a single block or district in San Francisco before World War I, housing discrimination against black residents steadily increased in the 1920s, leaving the Western Addition to become one of the few districts open for African Americans and other nonwhites.(44) As San Francisco lawyer and African American civil rights activist Edward Mabson remarked, housing discrimination against African Americans and other nonwhites made it “almost impossible for us to find places to live” anywhere but the Western Addition.(45)

A Works Project Administration travel guide noted that the district’s black population was international in nature, represented nearly every “State in the Union, Jamaica, Cuba, Panama, and South America.” When these residents were combined with a large Japanese community and immigrants from around the world, the district represented one of the most diverse urban spaces in the city if not the nation.(46) The Chinatown district was perhaps the most segregated in the city, and, as in other ethnic neighborhoods, many settled there to ease the transition to a new life and nation. But when Chinese residents attempted to expand their residential boundaries or move to other districts, whites often greeted them with “threats, bombs, and open violence.”(47)

Grant Avenue at Jackson Street, 1926.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

The substandard housing and racial diversity in many of these working-class districts contributed to negative narratives that paved the way for slum clearance and public housing. Landlords built units below ground, which contributed to rumors of a vast underground network of tunnels and rooms. The press sensationalized these subterranean spaces and linked them to Chinatown’s alleged vice, disease, and exotic rituals and practices—even though district businesses catered to all ethnic groups, and underground rooms existed in other parts of the city.(48) In other parts of the city, housing reformers highlighted the growing problems of crowded, low-quality housing conditions and warned that San Francisco would suffer the social as well as physical consequences of bad housing. Narratives of the “slum” and its negative social consequences proved important for both public housing and urban redevelopment policies in the coming decades.(49)

The substandard homes in San Francisco neighborhoods and the growth of racial discrimination did mirror national trends, but the political climate in San Francisco, like that of the nation as a whole, ensured little government intervention into the real estate market. Across the Atlantic in Europe, housing reformers were more successful, tapping the power of labor unions and political parties to build what became the Modern Housing movement. To achieve their goals, Europe’s housing reformers publicized the social costs of substandard housing and promoted a vision of economic rights for citizens that included quality housing and well-planned neighborhoods. Their vision involved building mass-produced working- class housing (public, limited-dividend, and cooperative) that would include space to foster working-class solidarity and culture. Meeting space in housing projects, for example, would bring tenants together to discuss art, politics, and community. Architecture and planning, these reformers believed, could create a shared experience among tenants that would increase civic and political participation.

The Modern Housing movement did not solve Europe’s housing problem, but it did bequeath council houses in England, worker palaces in Vienna, cooperative developments in Sweden, mass-produced apartments in the Soviet Union, and modernist projects in Weimar Germany. In addition to providing attractive living environments, gardens, and units with plenty of light and space, these projects typically offered space for social events and private and cooperative businesses. The environment was conducive to civic and political participation for tenants living in and near them—all at affordable rents. And the Modern Housing movement helped make housing an economic right of citizenship across Europe where nations were building welfare states through social programs and legislation.(50)

In the United States during the 1920s, builders added homes and apartments to the nation’s housing stock, yet homeownership was out of reach for two-thirds of workers, and at least a third of the nation’s population, including San Francisco’s, lived in substandard dwellings—rented or owned. U.S. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover approached the nation’s housing problem as he had approached problems in other industries. Guided by a vision of associative liberalism, Hoover believed government officials should work with private sector associations, such as business groups and civic organizations, to formulate a voluntary, collective plan to address economic problems. In housing, he created the Division of Building and Housing to encourage industry leaders to make homes more efficient, more affordable, and easier to finance. Hoover also worked with a number of private housing organizations to promote private homeownership and a suburban ideal grounded in traditional gender roles and good housekeeping. Working with these institutions, Hoover brought some standardization to the home construction and finance industry, but affordable homes remained unavailable to many households, while substandard housing dotted neighborhoods across the nation.(51)

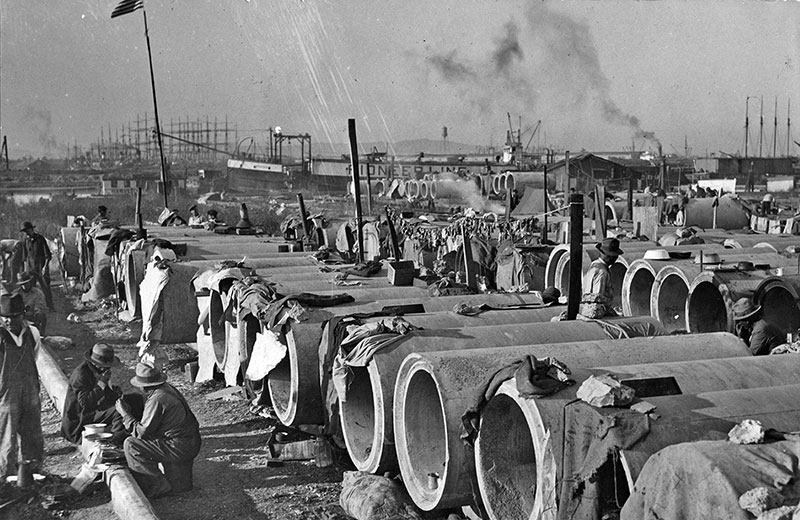

San Francisco residents take shelter in "pipe homes" during the Great Depression.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

previous article • continue reading

Notes

43. CCIH, A Report on Housing Shortage (1923); SFHA, 1939 Real Property Survey (1940); Works Projects Administration in Northern California, San Francisco: The Bay and Its Cities (New York: Hastings House, 1947), 220–28; Issel and Cherny, San Francisco, chapters 1–3; Cinel, From Italy to San Francisco, chapter 5; Tomás F. Summers Sandoval, Latinos at the Golden Gate: Creating Community and Identity in San Francisco (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Frank R. Quinn, Growing Up in the Mission District (San Francisco Archives, 1985); Howell, Making the Mission.

44. Grievance Committee Report of San Francisco Branch, NAACP, March, c. 1925, Folder 423, Box 97–21, Stewart-Flippin Collection, MSRC; Charles Spurgeon Johnson, The Negro War Worker in San Francisco: A Local Self-Study (San Francisco: Y.W.C.A and American Missionary Association, 1944); Katherine Stewart-Flippin, Transcripts of Oral Interview 1977–78, Black Women Oral History Project, Radcliffe College, 68; Albert S. Broussard, Black San Francisco: The Struggle for Racial Equality in the West, 1900–1954 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993); Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 Through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994).

45. Edward Mabson to Robert Bagnall (April 9, 1923), Folder 389, Box 97–20, Stewart-Flippin Collection, MSRC; Johnson, The Negro War Worker; Stewart-Flippin, Oral Interview 1977–78; for Mabson biographical information, and attempts by whites to prevent integration in housing and employment, see Broussard, Black San Francisco, chapter 1.

46. “State in the Union” quote on 285 from Works Project Administration, San Francisco: The Bay and Its Cities, 282–303; Issel and Cherney, San Francisco, 66–70, 188–90.

47. Quote in School of Social Studies, San Francisco College, Living Conditions in Chinatown (1939), Folder “Hogan—Living in Chinatown,” Box 2, Records of the Central Office: Records of the Office of the Central Historian, Records Relating to the History of the Agency (“Historical File”), 1934–48, PHA, RG 196, NARA/CP; Judy Yung, Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); Nayan Shah, Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

48. Ibid. Quote in Living Conditions in Chinatown. For the relationship between racial stereotypes and urban reform, see Shah, Contagious Divides; Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom’: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), especially chapters 6 and 9.

49. San Francisco Housing Association, Annual Reports (1911 and 1913); “Commission Talks of Building Laws,” San Francisco Call (April 25, 1911); Lawrence J. Vale, Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

50. Bauer, Modern Housing; Radford, Modern Housing for America; Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings.

51. Wood, Recent Trends; Weiss, The Rise of the Community Builders; Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings, 382; Janet Hutchison, “Shaping Housing and Enhancing Consumption: Hoover’s Interwar Housing Policy,” in Bauman, Biles, and Szylvian, From Tenements to the Taylor Homes; Ellis W. Hawley, “Herbert Hoover, the Commerce Secretariat, and the Vision of an ‘Associative State,’ 1921–1928,” Journal of American History 61, 1 (June 1974): 116–40; Guy Alchon, The Invisible Hand of Planning: Capitalism, Social Science, and the State in the 1920s (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985); Radford, Modern Housing, 12–57; Mark Hendrickson, American Labor and Economic Citizenship: New Capitalism from World War I to the Great Depression (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.