Miller & Lux and the Dirty Plate Route

Historical Essay

by David Igler

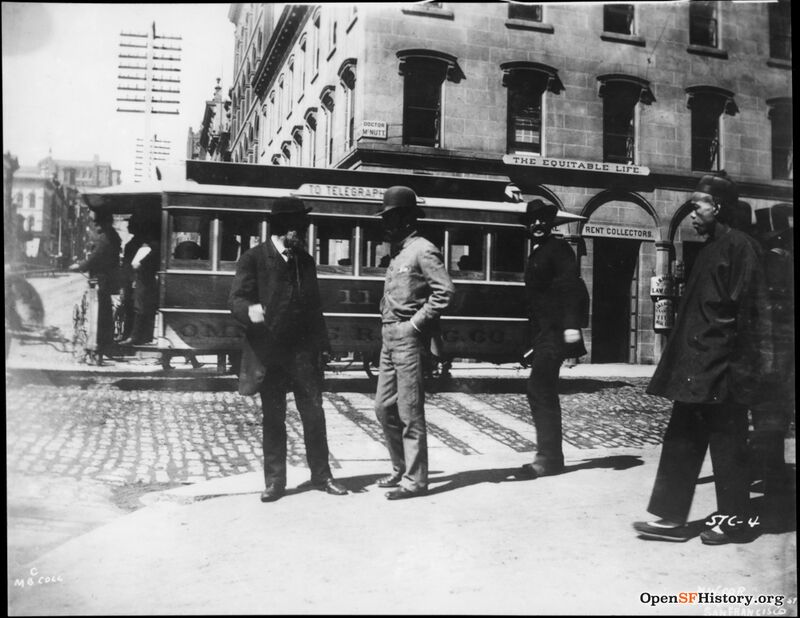

The Miller & Lux offices were in the Parrott Building, right behind the streetcar in this 1889 photo looking west across Montgomery on California.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.2032

Miller & Lux’s operated amidst the nexus of the West’s leading firms: the Central Pacific Railroad; the Pacific Mail Steamship Company; the Bank of California; the Union Iron Works; the California Redwood Company; the New Almaden Mining Company; and the emerging Comstock syndicates headed by William Sharon, George Hearst, D.O. Mills, and the partnership of Mackey, Fair, Flood & O’Brien. Highly centralized, ambitious, and operating in different business sectors, these firms shared a vision of western industrial development that matched the region’s vast terrain.

Henry Miller's luxurious mansion on Rincon Hill, occupying the corner of Harrison and Essex from 1882 until it burned down in the fire of 1906.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

Miller & Lux began a policy during the 1870s of feeding tramps and wandering laborers at their ranches. The [Chinese] cooks immediately complained about the increased workload. In particular, they objected to washing the extra dishes used by the unemployed migrants, and they ultimately refused to do so. Thereafter developed the Dirty Plate Route: tramps still received a free meal at Miller & Lux ranches, but the food arrived on the dirty plates of employees who had finished their food.

Hobos walking down the rail tracks, c. 1920s.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Bindle stiffs, tramps, hobos, hard travelers, migrant laborers—the terms all signified the wandering unemployed that inhabited the nation’s rural areas during the late nineteenth century. Red Lizard, a rail-riding hand-out-seeking rover, embodied one sort. He crisscrossed the West and frequently hit the Dirty Plate Route with fellow travelers such as Spoonbill, Seldom-Seen Murphy, Gunnysack Swede, Holy Joe, and D.C. Slim. Red Lizard enjoyed the route and characterized it as a luxury that “had no equal in life’s poker game for a man without a pair.” …

Miller & Lux developed the Dirty Plate Route in response to people like Red Lizard and Matthews. By the mid-1870s, wandering laborers and tramps filled California’s interior valleys, and according to the San Francisco Bulletin, “the evil [they represent] is assuming large proportions.” Many rovers deliberately searched for work. The worst elements sabotage railroad lines, begged meals, burned barns, and created a “serious nuisance” to citizens and property alike. Few residents attempted to distinguish the “careless rover” from the worker actually desiring employment, a problem only exacerbated by the large number of migrant harvesters and threshers seasonally employed on large-scale Central Valley wheat operations. Miller & Lux, like other ranchers, viewed the wandering unemployed as a grave threat to its property. They could drive off cattle, pull down fences, or leave cattle gates open. Miller particularly feared the intentional or unintentional burning of haystacks, an act that would only increase in regularity if he did not generate goodwill among the migrants. Feeding tramps at the firm’s ranches seemed an acceptable expense for insuring the protection of both cattle and haystacks.

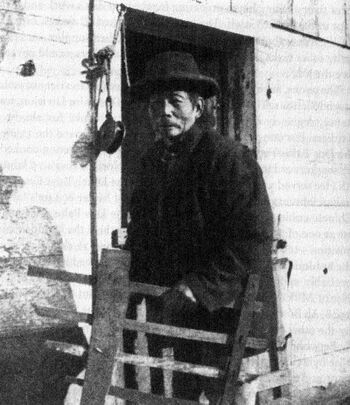

This photograph, captioned "Ah Jim, 95 years old, Chinese Ranch Cook," appeared in H.A. Van Coenen Torchiana's 1930 novel, California Gringos, based on Miller & Lux.

Photo: courtesy David Igler

By the 1890s, Miller & Lux often fed up to 800 migrants a day at two dozen different ranch houses. Some bindle stiffs took the “grand whirl” throughout Miller & Lux’s “entire reservation,” receiving their free meal at one ranch before ambling off to the next one. Others limited themselves to an “inside whirl” or “southern whirl,” thereby accepting the firm’s generosity in just one part of the San Joaquin Valley. The meals varied little: plentiful beef, boiled potatoes, and sometimes fruit or vegetables from the ranch garden. The dining procedure varied even less. The tramps waited for Miller & Lux workers to eat and vacate their seats—leaving the dirty plates behind—at which time first-come, first served ruling the dining hall. The Chinese cooks managed this procedure, and by one account, “the China cook gets after [the tramps] if they attempt to crowd in among the work hands.” After meals, the employees returned to work on the bunkhouses while the unemployed moved on to their roadside “roosts” or the ranch barn. Those actually seeking work could gather leads at the ranch house from the foreman or fellow rovers. The true tramp rarely signed on for consistent work, but he did occasionally labor long enough to “choke off a piece of booze money.” Everyone in the valley understood the Dirty Plate Route’s preventive function, as set in verse by one frequent traveler:

- Here’s to Uncle Hank, who lets us satisfy

- The belly chiefly, not the eye.

- Keeping the barking stomach wisely quiet,

- Less with a neat than a needful diet

- For he, from sad experience knows,

- The hungrier man gets, the more desperate he grows.

Men at work on Miller & Lux's San Emigdio Ranch, c. 1888.

Photo: Carleton Watkins, Library of Congress

The Dirty Plate Route’s second, and possibly more important, rationale was aimed at the firm’s own employees. Miller & Lux maintained three objectives in relation to its unskilled laborers; to keep wages as low as possible, to limit overall labor costs by hiring workers according to daily demands, and to prevent all possible strikes for higher wages. These objectives demanded an ever-present reserve pool of laborers that could fill shortages caused by employees walking off the job. The firm’s geography worked against this goal, especially in the San Joaquin Valley, where vast distances separated the properties, and labor shortages could arise on short notice. The Dirty Plate Route resolved these risks by guaranteeing an unemployed army streaming across Miller & Lux lands. For every dozen bindle stiffs like Red Lizard who entertained few thoughts of working an irrigation shift, there were a few laborers like Joseph Matthews whom the firm could count on for temporary work. In the end, the migrants’ constant presence—whether they intended to work or not—served Miller & Lux’s goal by remaining employees of their replaceable status and insecure existence.

Feeding tramps and migrant workers was nothing new in rural America. The Dirty Plate Route simply institutionalized and capitalized on what many rural Americans had practiced for over a century.

Miller & Lux team hauling grain to Salt Slough warehouse, 1890.

Photo: courtesy Milliken Museum, via Immigrant Entrepreneurship

Miller & Lux's Stockton ranch, c. 1887.

Photo: Carleton Watkins, Library of Congress

In July 1915, [Miller’s son-in-law and new President of Miller & Lux, J. Leroy Nickel] curtailed the firm’s longtime practice of feeding tramps and unemployed workers in the valley. The resulting arson showed exactly why Miller had established the Dirty Plate Route decades earlier: towering haystacks burned across Miller & Lux ranches following Nickel’s order.

Alfalfa harvest at Miller & Lux's Stockdale Ranch in Kern County, 1890s.

Photo: Carleton Watkins, Library of Congress

This excerpt from Industrial Cowboys Miller & Lux and the Transformation of the Far West, 1850-1920 is used with permission. © David Igler, University of California Press: 2001