Laguna Honda Hospital

Historical Essay

by Dr. Victoria Sweet, excerpted with permission from God's Hotel: A Doctor, A Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine

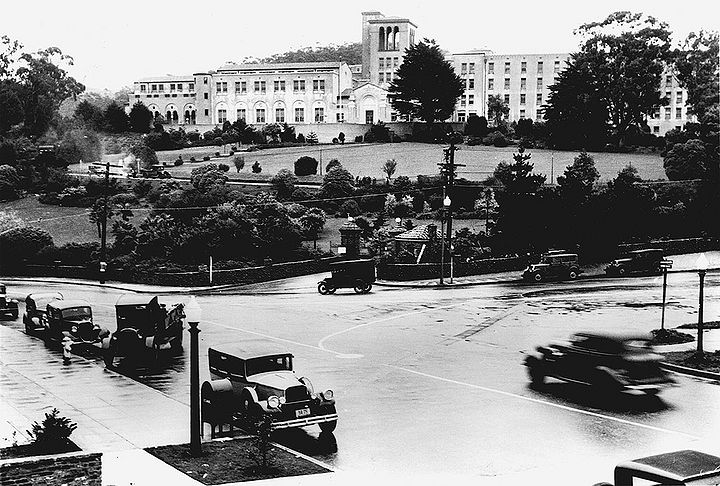

East at Laguna Honda Blvd. and Dewey Blvd. with Laguna Honda Hospital on hill above, Feb. 23, 1936.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, courtesy C.R. collection

Laguna Honda Hospital as seen from the slopes of Edgehill Heights, 2023.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

I was just starting to write God’s Hotel when workmen began demolishing the century-old Clarendon Hall.

They started with its west and south wings, harvesting windows and window frames, faucets and sinks; then they moved to the East Wing. They took Clarendon Hall apart the way termites take things apart, leaving the outside intact until the end. Then they disconnected the water, gas, and electricity. It reminded me of what happens when a patient is declared brain-dead: The healthy organs are harvested, then the oxygen is disconnected, the IV taken out, and the EKG turned off. After that, the workmen began on the outside, taking away copper pipe and clay tiles, sculptural elements, landscape. Finally Clarendon Hall was ready.

The old Almshouse that was replaced by Laguna Honda Hospital, seen here c. 1890.

Photo: Private collector and openhistorysf.org

Alms House, 1890s.

Photo: courtesy Victoria Sweet

Since I'd missed the barbecue for the blowing-up of the bridge that once connected Clarendon to the main building, I made sure to be present for its demolition. When the day came, I walked over. From the outside, the building still looked as elegant as ever, an Edwardian one hundred years old.

With a few others, I stood behind the wire fence and watched. The greenery around the building had been taken away; and in the dirt that remained was a machine that looked like a praying mantis made out of metal. It lumbered with neck jutting out and jaws open until it came to a corner of the building. It stopped, took a bite out of the tiled roof, tore a piece off with a little jerk, and threw it on the ground. Then it lumbered to its next position, took another bite, and threw the next piece on the ground. It went all round the building like this, and the insides of Clarendon were gradually exposed. It was a tough old building, though, and pieces of cement and old steel rebar stuck out of its walls for quite a while. But bit by bit it diminished. By the end of the day; Clarendon Hall was rubble; by the next week, the rubble had been cleared, the foundation filled in, and the ground made ready for whatever would come next.

Two weeks later, Sister Miriam resigned. She did not go gentle into her good night, however. Instead, she wrote an article for the local newspaper about how it broke her heart to say good-bye to the beautiful spirit of Clarendon. It was a symbol of the unique and warm atmosphere of Laguna Honda that for so long had served the city's most vulnerable population, she wrote. And she warned: Draconian cuts were being made to the hospital, though oh-so-quietly. The number of patients had already been cut by a third; the hospice chaplain laid off; the day program terminated—all due to the "budget crisis." Yet there was still enough money to hire Wide Angle Communications—the mayor's communication consultant—to support "the hospital's journey from institution to community." Citizens should keep a close eye on what was going on at Laguna Honda, she ended.

In addition to her article, Sister Miriam nominated her successor, Sister Margaret. In appearance, Sister Margaret was as different from Sister Miriam as she could be. Black skin, black hair, dark eyes, lilting Jamaican accent, small blue and white veil perched modestly on her head. But in temperament, they were just alike, as administration would soon discover.

Front of Laguna Honda hospital, February 2016.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Same facade, 1926.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Meanwhile, Mr. Conley was working on next year's budget. It would be different from any other budget the hospital had ever had, he thought, because, with the next year's move to the new facility; it would have to fund both new and old hospitals at the same time. He was wrong about the move, but right about the budget. It would be different from any other budget the hospital had ever had because, for the first time, the budget would be cut.

Now a budget crisis came every year and had a pattern. It would begin with terrifying predictions of immense deficits, which would increase as the unions negotiated their contracts and politicians jockeyed for staff. There would be demonstrations against proposed cuts, and a deeper projected deficit would be announced, followed by pleading and compromise. Then, along about May, there would be the stunning discovery of millions of dollars of revenue that the controller had somehow overlooked, with reconciliation, smiles, and a budget bigger than the year before.

But this year the budget crisis was different. Times were, in fact, bad. People would, in fact, be laid off, and public health services would, in fact, be cut. The only question was: Which ones?

The medical department was in a particularly bad position. Dr. Stein did not like us and would not save us from any cuts. Dr. Dan had already laid off the night and weekend doctors, and we had no administrative staff whose positions he could merge and rename. Plus, in preparation for the move, the number of our patients was going to be decreased by 20 percent. So it was hard for Dr. Dan to get around the fact that he would have to cut his doctors by that same amount.

Except that the doctors did generate revenue when we saw patients and Dr. Dan reasoned that if he could show Mr. Conley that the medical department paid for itself, at least partially, it would decrease the number of doctors he would have to lay of£ So Dr. Dan began collecting data on each physician's services. Since this was not on any computer, it meant that he had to go around to every ward and look at every chart, and keep an account of what each of his doctors produced. Soon his "Productivity Reports" began to appear in our wooden mailboxes, proving how much we earned every month for the city, in theory. Although not in practice, because the billing department had no idea how much it billed for our services or any other services, nor how much it received. However, according to his accounting, the medical department earned one-half of its budget, and Dr. Dan hoped for a happy result to his efforts.

Which made me conclude that Dr. Dan was a closet idealist. Because his figures did not matter to Mr. Conley, and Dr. Dan still had to cut five physicians from his budget.

Whom would he cut? What criteria would he use? Dr. Dan spent a weekend reflecting. He would use seniority, he decided, but not mainly; he wanted young blood as well as old, energy as well as experience. He would look at board certification, comfort in doing procedures, willingness to work full-time, and other unspecified characteristics. He sketched out a form, printed it out, and called a meeting of the medical staff.

It was a short meeting. Dr. Dan explained the budget problem and handed out his forms. We looked at them. Were they mandatory?

No, they were voluntary. Although it would be easier for him to make his decision if everyone filled out a form. If someone didn't fill out a form—well, he would just have to fill it out himself

After the meeting, a big sign appeared in Jerrie's office reminding us to fill in the forms, and there was a folder below the sign that stayed almost empty.

Old hospital wings, doomed to destruction.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

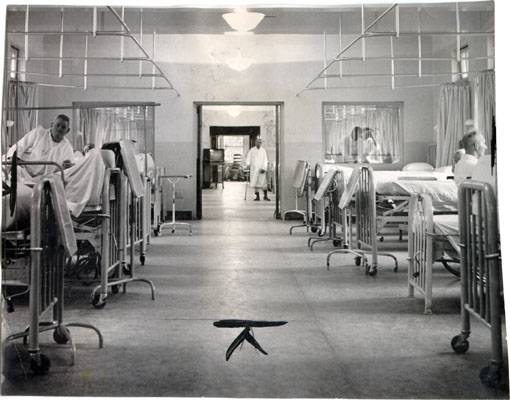

Laguna Honda ward, 1959.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Laguna Honda ceramics class, 1956.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Then Dr. Dan called another meeting.

The budget had taken a turn for the worse, he announced, and Dr. Stein was demanding that in addition to the five doctors to be laid off in the next budget, four additional doctors had to be laid off this year. He would let us know who they would be the next week. And now Mr. Conley had a few things to tell us.

Then Mr. Conley came into the room. He looked tired. His red hair was thinner and grayer and so was his beard; his eyes were weary, and his voice was hoarse. He wanted to let us know that marketing had presented its branding campaign, and we now had a tagline and a value statement. Our new tagline was: "Laguna Honda—A Community of Care," which, he was sure we would agree, was a good description of the place. Our new value statement was: "Our Residents Come First." Marketing was still working on our new logo, our new mission, and our new name.

At this, the medical staff came to life. Heads came up from charts, journals, and tabletops. Mr. Conley was taken aback by the sudden attention.

Yes, a new name. Laguna Honda had to be repositioned and rebranded; it would not do for the new facility to be seen as an old-fashioned almshouse for the poor. The new Laguna Honda was going to be a Center of Excellence, focusing on health, wellness, and rehabilitation; and marketing had decided, therefore, that "Hospital" should be taken out of our name.

Mr. Conley looked around. Everyone was staring at him. No one spoke. And then everyone spoke at once.

If Laguna Honda was not a hospital, we asked, then who were those sick, demented, frail, one- or no-legged, coughing, yellow people we took care of every day? In their wheelchairs, gurneys, and beds? "With their IVs, feeding tubes, catheters, casts, oxygen, and tracheotomies? What were they doing here? Where would they be in the new, nohospital Laguna Honda? Would they be elsewhere?

Mr. Conley didn't hang his head exactly, but he did stop and stare into space for a moment. A vision went past his tired blue eyes. Those patients. The ones whose beds he sat on, whose hands he, even he, Mr. Conley, BS, MPH, executive administrator, held.

"Hospital" stayed in our name.

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/NewOldParadigmsInMedicineFeb102016" width="500" height="30" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

A discussion on "New (Old) Paradigms in Medicine" held on Feb. 10, 2016 as part of the Shaping San Francisco Public Talks series. (apx. 2 hours)

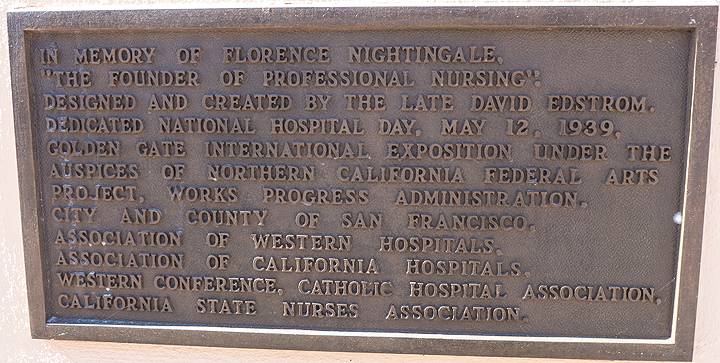

Statue and plaque in front of main entrance to Laguna Honda, created by WPA.

Photos: Chris Carlsson

Four elements, murals by Glenn Wessels, 1934.

from God's Hotel: A Doctor, A Hospital, and a Pilgrimage to the Heart of Medicine by Victoria Sweet, copyright © 2012 by Victoria Sweet. Used by permission of Riverhead, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.