How The SF Law Collective Fought For Change In The Mission

Historical Essay

Hoodline is an online news publication that covers the issues, people, community organizations and local businesses that make up San Francisco neighborhoods. The following article is by Shane Downing and was first published on October 26, 2016.

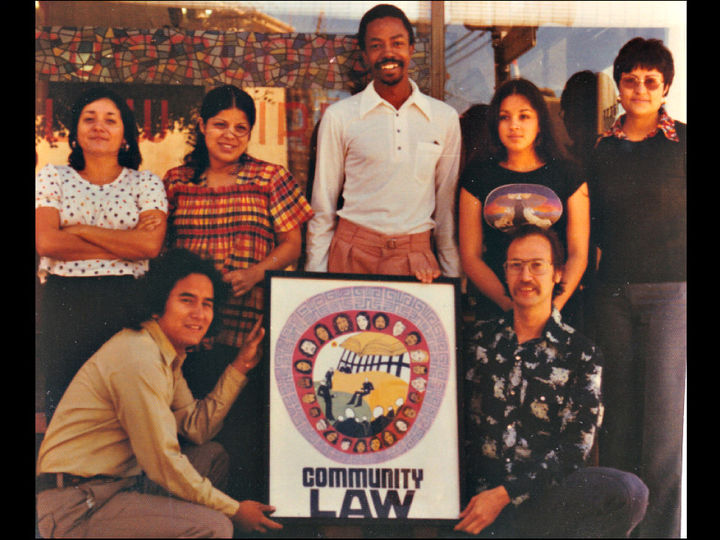

The San Francisco Law Collective.

Photo: Paul Harris/SF Law Collective

Back in 1970, Paul Harris and Stan Zaks were part of a new generation of law students. Coming out of the anti-war and civil rights movements, the two Jewish lawyers, friends since junior high in Los Angeles, set up a multi-racial law collective in San Francisco’s Mission District. Their intention was to represent the neighborhood’s diverse—yet marginalized—community groups.

A law collective meant that lawyers, secretaries, and legal workers were all equal partners: workers received equal salaries and had equal decision-making power.

"We had equal decision-making when it came to working conditions and things like who to hire, how much our salaries were, who to fire, and what cases to take," said Harris. "It didn’t mean that the secretaries sat down and told me how to do my closing argument.”

The SF Law Collective in front of its 18th and Dolores storefront (1973).

Photo: Paul Harris/SF Law Collective

The concept of a law collective wasn’t unique to San Francisco. According to Harris, approximately 40 law collectives that were established around the United States between 1969 and 1975, in cities like New York, Chicago, and Palo Alto. “We considered ourselves communist with a small 'c,'" said Harris. “We believed in equality.”

Harris and Zaks set up their office at the corner of 18th and Dolores, above what was then Good Karma Cafe. (They still own the building, which is now home to Dolores Park Cafe.)

“In 1970, the Mission was in the midst of intense organizing,” said Harris. Neighborhood legal aid offices in the city weren’t allowed to take political or criminal cases, he said, "so there were all of these multi-racial groups that needed help, and no lawyers in the neighborhood.” Within the first six months of opening its doors, the collective was representing five community groups.

Harris and Zaks hired their first two legal workers from the community. One of them was Bernadette Aguilar, who grew up in the Mission. At the time, Aguilar was working with Latin Americans United for Education, organizing to help Mission kids go to college.

She wasn’t familiar with the idea of a law collective when the two lawyers approached her. “I was just looking for a job,” said Aguilar. “I didn’t want to go downtown. I wanted to work closer to Dolores Park in the Mission.”

Aguilar earned $84.09 a week at the collective. “I’ll never forget that amount,” she said. “I had my experience growing up in the Mission, and I had connections in the neighborhood and knew what was going on, but I never would have expected to go to work and be an equal partner in a law firm. It was the greatest job I ever had.”

Members of the collective standing on the corner of 18th and Dolores (1971).

Photo: Paul Harris/SF Law Collective

According to both Aguilar and Harris, there was a lot of tension between the Mission's residents and the SFPD during the collective's '70s heyday.

“There was a police riot every year for the first three years of our practice,” said Harris, “By police riot, I mean there was one in Dolores Park where the police just swooped in and beat and arrested people. Every police officer in the Mission District was white, and there were almost no Latino police officers in all of San Francisco when we set up.”

The collective took on many police brutality cases, but they also represented groups like bilingual newspaper El Tecolote, the Native American Center, the People’s Health Clinic, and Los Siete de La Raza.

“The whole concept was to be the attorney for community groups, so that the community groups could build their power,” said Harris.

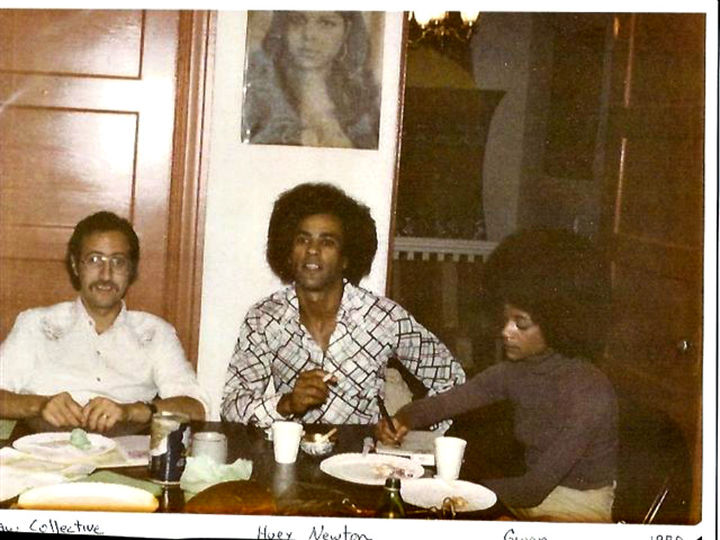

Black Panther leader Huey Newton and his wife, Gwen, visiting Paul Harris at the Law Collective's office.

Photo: Paul Harris/SF Law Collective

But exclusively taking pro bono legal cases for the good of the community wasn't economically sustainable for the law collective. “We had to make money,” said Harris. “So we had this thing that I called the godfather principle.”

The principle was simple: the collective made itself freely available to community groups, under the condition that when members of those groups got into car accidents or had their houses burn down, they had to bring those cases to the law collective—and pay.

“Probably 25 percent of our cases were personal injury,” said Harris, “but that made up 75 percent of our money.”

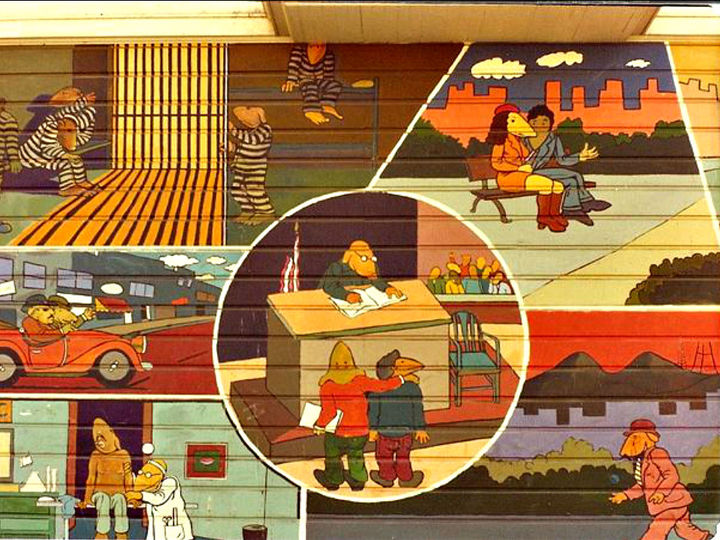

The Mission's second mural, painted by Michael Rios, on the side of the neighborhood's legal services building (1970-71).

Photo: Paul Harris/SF Law Collective

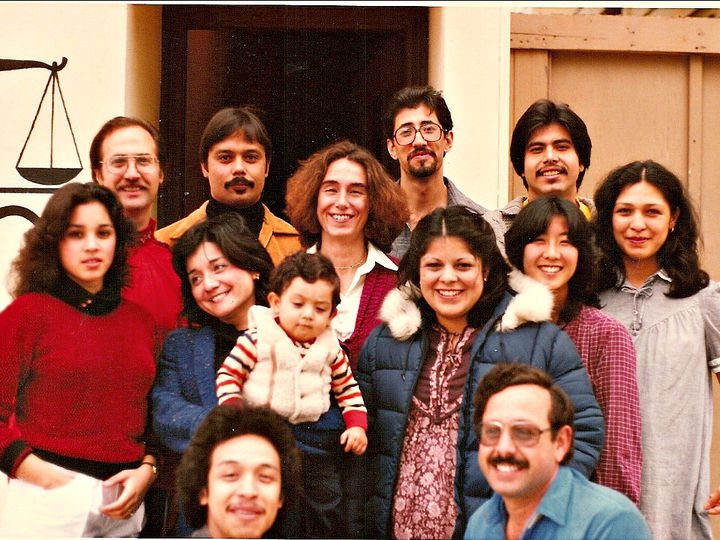

The collective's biggest challenge, Harris said, was building a "truly" multiracial law firm. There were so few people of color coming out of law school at the time, he said, and only a small percentage of them wanted to work in a collective.

“It wasn’t affirmative action,” said Harris. “it was our commitment to building a multiracial firm that would better serve the community.” When the collective disbanded after 16 years, four out of its six permanent members were people of color.

When asked what kind of cases the law collective would take on today if it were still around, Harris listed demonstration, immigration, and landlord-tenant cases.

“I’d also be involved with Black Lives Matter if I was still practicing,” he said. (Harris previously represented Huey Newton of the Black Panther Party, successfully defended Leonard McNeil for draft evasion, and was a pioneer of the black rage defense.)

The collective, pictured in 1980.

Photo: Paul Harris/SF Law Collective

The Law Collective came to an end in 1986 because of a number of factors, Harris said, including personal health issues, members wanting to go their own ways, and the nation’s economy.

“There are almost no collectives anymore,” said Harris. “In the ‘60s and ‘70s, there were collective bookstores, there were collective grocers and markets all over the country. It’s hard to continue that under capitalism. People fall back into individualism and greed and not being able to work together.”

Regardless, Harris, who was named one of the best criminal lawyers in the country three times by Best Lawyers in America, is proud of what he and his peers were able to accomplish at the San Francisco Law Collective.

“We prided ourselves on doing good legal work," he said. "Those 16 years practicing in an office with equality between people of all races that represented the people of the community was the most rewarding experience of my life."