Ewing Field Part Two

Historical Essay

by Angus MacFarlane

Continuing the saga of early 20th century baseball in San Francisco and the much-mythologized story of fog-bound Ewing Field.

Ewing Field, 1914.

1912-1914

THE WINDING ROAD TO EWING FIELD

The 1912 season began auspiciously for the Seals with an 8-7, 11-inning victory over the Oaks before 15,000 fans—the largest crowd in Rec Park history—for their 12th opening day victory in a row. Five days later 12,000 East Bay celebrants watched their team defeat San Francisco in the morning game of the Sunday double-header. In the afternoon contest, 14,000 Seals partisans witnessed another Oaks victory at Recreation Park. This was Oakland’s sixth straight win since their opening day loss. They would win another seven consecutive games under their new manager, Bud Sharpe, before losing again. For the next six weeks Oakland would lead the league while San Francisco hovered between 3rd and 5th place.

On May 18, with Oakland in first place and the Seals firmly settled in fourth, the Call’s front page blared the headline:

SEALS SHAME CIVIC PRIDE Dollar Policy Queers the Game,

Results, Not Promises Are Demanded By Fans,

Owners Are Killing The Goose That Lays The Golden Eggs.

This was the first salvo in a weeklong series of Call hit pieces against the Seals. According to the Call, Ewing, Ish and other shareholders in the Recreation Park Association (the corporate name for the Seals and their holdings) were growing richer each year at the expense of the team.

The San Francisco baseball club has been a gold mine since the close of the season of 1908. The dollars have been rolling into the box office for five days a week and seven and a half months a year. And during this time San Francisco has captured one pennant—that in 1909. When we Seal rooters want to see a good game, we have to depend upon the Oakland team to give it to us. Oakland always puts a strong aggregation in the field. It has been a pennant contender for two years straight and is leading the league now.

It was public knowledge that Ewing still had a majority interest in the Oakland club and the sentiment of many readers who responded to the Call’s articles was that Ewing was obviously favoring his Oakland holdings over San Francisco. This completely and conveniently overlooked the fact that Ewing had surrendered all of his Oakland stock and voting rights to his trustee, Ed Walter, in 1906.

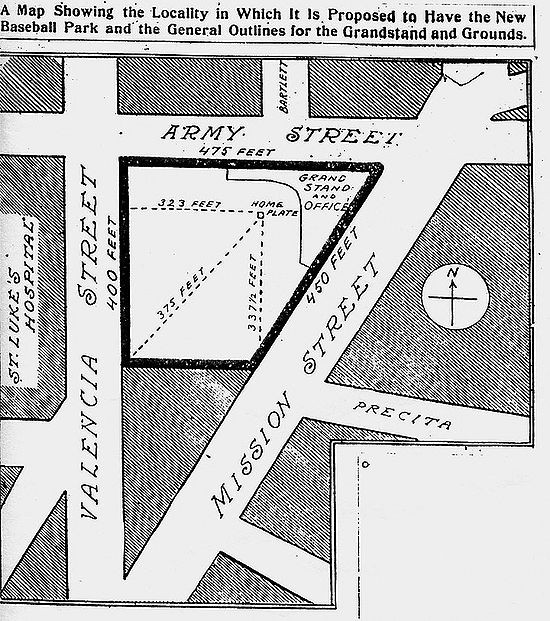

On September 22, while the Seals were in their accustomed place—a distant fourth to the front-running Oaks—the Chronicle broke the news that Ewing planned to build a new stadium on the triangular block bounded by Mission, Valencia and Army Streets across the street from St. Luke’s Hospital. The Seals would purchase the property outright. The planned stadium would be built of steel and concrete and would dwarf Recreation Park in outfield dimensions and in seating capacity— up to 20,000. The total cost for the new facility, including the purchase of the property (toward which $10,000 had been placed as a deposit) was over $250,000.

Sept. 22, 1912 SF Chronicle drawing of proposed new stadium.

A month later Oakland swept a double header from Los Angeles on the final day of the season to win its first pennant in the closest PCL race in history. Two days later Ewing went back east to inspect stadium designs.

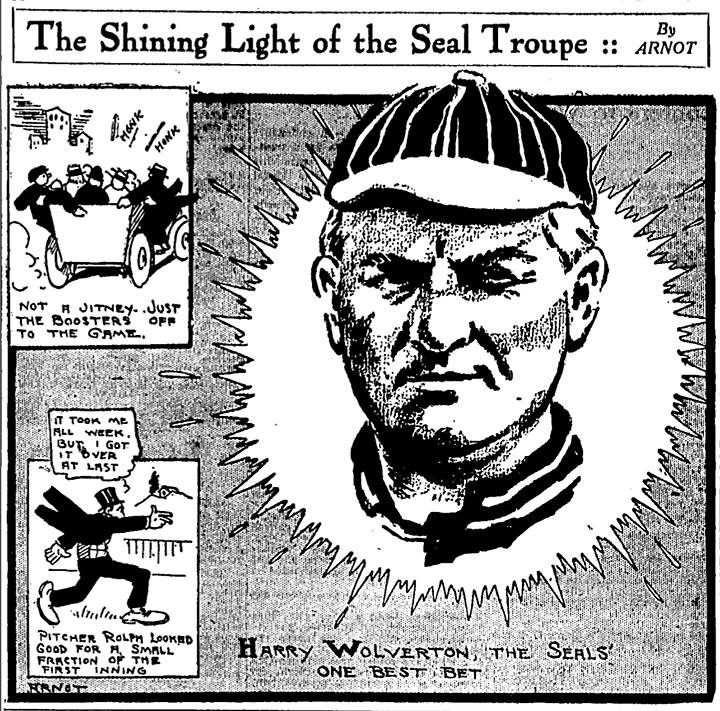

The first two months of the post season were exceptionally eventful. On November 6 Harry Wolverton, the manager who had turned Oakland around in 1910 and 1911, was fired by the Yankees following a horrendous 50-102 season. Ten days later the Sacramento Senators hired him as their manager for “probably the highest salary in the league [for a player or a manager]”. The Grey Wolf immediately went to work signing players to improve on Sacramento’s last place finish in 1912.

Then, in a one-week stretch between December 5 and 12, the Bay Area baseball world was shaken as it hadn’t been shaken since 1906. In that week it was reported that Ewing’s new stadium plan was in jeopardy; Oakland finalized a deal for a new $150,000 stadium; “an unnamed syndicate” had leased Recreation Grounds for 20 years once the current lease expired on May 1, 1916; Ed Walter resigned as president of the Oakland Oaks.

The connection between all of these events was made clear in the Bay Area newspapers beginning December 9. Three days earlier, on Friday December 6, Ed Walter asked Cal Ewing to meet him. Whatever Ewing might have been expecting at this meeting, it definitely wasn’t what Walter presented.

While Ewing was preoccupied with stadium matters, Walter had carefully, and secretly, assessed the ballpark situation in San Francisco and concluded that there were no suitable locations for a new ballpark. Recreation Park was the only viable venue in the city. Walter then revealed to Ewing that he had used a respectable realty company as a front to obtain a 20-year renewal on Recreation Park’s lease beginning May 1, 1916. Through his front, Walter pointed out to the Judson Company that Ewing had already spent $10,000 toward the purchase of the Army Street site. Therefore he obviously would not be inclined to renew the Recreation Park lease in 1916. Accordingly, Walter made the Judson Company an offer they couldn’t refuse. Which they didn’t.

Armed with the 20-year lease, Walter laid all of his cards on the table. He told Ewing that he knew the Army Street stadium plan was fatally flawed, and that if Ewing and the Seals wanted to play baseball in San Francisco it could only be at Recreation Park. To that end, Walter offered to sell Ewing the lease. Up-front he demanded Ewing’s 10,000 shares of Oakland stock valued at $10 per share ($100,000) and a $6,000 “bonus”. Then he wanted monthly “rental” at $1,000 per month for the first five years of the 20-year lease ($60,000); $1,250 per month for the next five years ($75,000); and $1,500 monthly rental for the final ten years ($180,000) for a grand total of $421,000.

As leverage, Walter threatened Ewing that if he refused these terms, Walter would destroy his reputation by revealing his involvement in syndicate baseball. He gave Ewing till the following Monday to consider the deal.

Ewing immediately refused the blackmail terms.

Two days later Walter resigned as President of the Oakland baseball club. The following day, December 9, the blackmail scheme was all the news.

Ewing’s sense of betrayal was profound. It was no secret that he was a majority stockholder in both the Oakland and San Francisco clubs, but he reminded everyone that he had surrendered his Oakland interests to Walter in 1906 to act as his trustee. In fact, it was Ewing who had brought Walter into the Oakland organization in 1903 as club secretary. Ewing also reminded the public that he lost money on his Oakland holdings till the end of 1909 when it turned its first dividend. He had publicly joked that it was a white elephant that he couldn’t give away.

Over the years Walter became more than Ewing’s trustee for his Oakland interests; he was Ewing’s friend and confidante. It was in this capacity that Walter learned of Ewing’s stadium plans and problems, and used that confidentially obtained information to his advantage.

The Pacific Coast League was holding its annual meeting in Sacramento on December 9, the day that the blackmail story hit the papers. The league backed Ewing, recalling what he had done to save baseball in 1906 and his tireless work as PCL president. It passed a resolution affirming that there was no truth to Walter’s syndicalism charge.

Coming to Ewing’s defense, State Senator Frank Leavitt, a prominent Oakland stockholder, said of Walter’s role as president:

[Walter] has dictated the policy of the club, hired and fired managers, players and the like, and in fact has run the club himself. Not one of the directors or stockholders has ever interfered with his running the club.

Henry Berry, owner of the Los Angeles Angels also spoke out on Ewing’s behalf:

Three or four years ago he couldn’t give his stock away. The park deal was a flagrant hold- up and Walter cannot be criticized too severely for his actions.

The Call’s May hit pieces on how poorly the Seals were playing—and being managed— clearly documented that Ewing was in no way using his dual ownership to the Seals’ advantage—the legal definition of syndicalism.

The wild week ended with the Chronicle’s December 12 heading EWING WILL SELL HIS BASEBALL HOLDINGS AND TOUR WORLD. Truthfully, Cal Ewing wasn’t throwing in the towel and conceding defeat to Walter. The accompanying story explained that Ewing had promised his wife that he would retire from baseball after the end of the 1915 season.

It takes up all of my time and carries with it countless worries and cares. I will be 50 years of age by 1916 and think I have earned the right to rest and enjoy life for the rest of my days.

But before I do get out of the business, you can rest assured that San Francisco will have a modern ballpark and the affairs of the Coast League will be in ship-shape.

E.N. Walter had planned to use the charge of syndicate baseball as a club to hold me up, but I came out with a clean breast of facts and nothing but the facts. I admitted that I and my uncle and partner, Frank Ish, owned the control of the San Francisco and Oakland clubs but I defy anyone to prove that I dictated in the running and policies of the Oakland club. Walter has not even stated that I took a hand in the affairs of the Oakland club.

On December 13 Ewing finally sold his stock in a deal “that had been hanging fire for many months and that the Walter controversy had nothing to do with it.”

Ewing was no fool and he had to have known from the very beginning that Recreation Park was inadequate. How long he had been seeking a new stadium site is not known, but undoubtedly he was looking for something at the expiration of Rec Park’s lease in 1916. The fatal flaw in the Army Street plan was a city ordinance prohibiting noise near hospitals. A ballpark across the street from St. Luke’s Hospital was in clear violation of that law.

While “men in close touch with real estate in San Francisco declare that there is no place available for big enough grounds to build a park,” Ewing maintained that he had other places in mind if the Army Street plan didn’t work out. If the other sites weren’t viable and Ewing was forced to remain at Recreation Park, he had contingency plans to renovate the field.

But that option was gone now that Walter had the lease. Walter may have indeed been right about Recreation Park. As of this moment, Ewing Field became an inevitability.

On April 5 Ewing argued before the San Francisco Board of Supervisors for a noise ordinance waiver. The hearing was continued to April 22 when the ordinance was upheld.

With the Army Street site now lost and his contingency plans for Rec Park dashed, Ewing found a new possibility on College Hill near the old St. Mary’s College on property owned by the Archdiocese of San Francisco. The church’s real estate agent also showed Ewing another College Hill site as well as two parcels the Church owned on Lone Mountain.

One was called St. Ignatius Stadium on the western side of Lone Mountain on the site of today’s Negoesco Soccer Stadium at Golden Gate and Parker Avenues. It measured 520 x 336 feet. The other site was a 550 x 550 foot parcel on the eastern side of Lone Mountain. Both sites were much larger than Recreation Park, but St. Ignatius Stadium had the dual liabilities of being exposed to the prevailing westerly winds and having a short right field.

In a fateful decision, Ewing chose the site across Masonic Avenue from Calvary Cemetery. The daily baseball news supplanted any stadium developments till the Chronicle headlined on October 11, 1913: SEALS NEW BASEBALL PARK LOCATED AT FOOT OF LONE MOUNTAIN Stands to Be Built in Time to Open Up Season of 1914

Recreation Park to be Torn Down

The Call added: SEALS AT LAST ASSURED OF SPLENDID NEW HOME

Ewing was quoted “It is absolutely certain that the year 1913 will be the end of baseball at Recreation Park. We expect to go to the grounds on Masonic Avenue.” The PCL season would end on October 26 followed by a mid-November visit by the New York Giants and Chicago White Sox who would play at Recreation Park on their around the world baseball tour. After the major leaguers left, Recreation Park would be dismantled with the lumber and grass going to the new park. Ewing concluded “Work will be started in plenty of time to ensure opening in the spring of 1914 at the new grounds, which will be patterned after the Oakland grounds.” The 550-foot by 550-foot parcel was over 300,000 square feet (6.9 acres), larger that both Recreation Parks combined.

Site of new Ewing Field at Masonic and St. Rose (red x marks the spot).

In a vital piece of municipal cooperation, the city gave permission for a spur streetcar track to be built from Geary to Turk and Masonic to handle the baseball crowds.

Ewing, ever foresightful and thinking of his patrons, announced two new amenities for the new stadium: sheds would be provided for “auto patrons” to park their cars for free; and two colored maids would be on hand to look after the fair patrons.

The site for Ewing’s new stadium on the eastern slope of Lone Mountain had an interesting history. In 1854, the same year that the San Francisco Chemical Works were being built on the site of the current home of the Seals, the city was faced with the problem of what to do with its increasing number of dead. Yerba Buena Cemetery, the city’s 14-acre cemetery bounded by McAllister, Market and Larkin Streets had filled and more room was needed.

That year private developers created a final resting place that was 25 times larger than Yerba Buena. Various religious denominations and fraternal organizations bought land for their members and the western cemeteries became a quilt of burial grounds. The Catholic Church owned a 49-acre plot called Calvary Cemetery, originally part of the much larger Lone Mountain Cemetery. Calvary was bounded by Turk and Geary Streets and Parker and St. Joseph’s Avenues.

As matters stood in 1914, the new stadium would be across Masonic Avenue from Calvary Cemetery and a block north of the 38-acre Masonic Cemetery. To the west of the stadium Lone Mountain rose about 160 feet above the playing field. On the western slope of Lone Mountain was the 27-acre Odd Fellow’s Cemetery. Approximately 100,000 were interred in these three sites.

The Seals’ 1913 finale at Recreation Park was on October 26, a 2-1 victory over the Venice Tigers, who had barely nudged the Seals out for 3rd place. Harry Wolverton’s Wolves were a surprising second.

Architectural plans for the new stadium were drawn up on October 30 and work began in earnest. Based on the six weeks it took to build Oakland’s new park (which had a similar design), the stadium was expected to be ready by February at the latest.

Also on October 30, an announcement appeared in the Examiner that undoubtedly drove strong men to strong drink: there would be no booze cage at the new field. The infamous fenced-off portion of the Recreation Park grandstand where patrons could freely imbibe and verbally assault the players was to be a thing of the past. No alcohol would be served at the new park.

On November 3 a 20-year lease with the archdiocese was signed. On November 11, Harry Wolverton became the owner of the Sacramento club.

Between November 13 and November 16 the White Sox and Giants played two games in Oakland and three at Recreation Park. In what was supposed to be the last baseball game ever played at the old ball yard, the White Sox defeated John McGraw’s New York Giants 5-4. Despite the loss, a karmic breakdown was rectified. John McGraw and his Giants were to have celebrated the opening of the Seals’ new park in 1907 but had been rained out. Now they participated in Recreation Park’s closing.

As the new year began, a steam shovel was brought in to dig into Lone Mountain’s sandy slope. Along with 25 to 30 four-mule teams doing the grading and leveling work, it was anticipated that in ten days the site would be ready for the planting of grass. (The decision had been made not to bring the sod from Recreation Park.) But first ten inches of soil nutrients would have to be added to the sterile sand. Ewing was proud of Recreation Park’s nationally acclaimed field and he wanted the new stadium to carry on the same tradition, but the planting was hampered by problems in obtaining the proper soil, as well as an especially rainy January. Despite these delays, Ewing was confident that the grandstands and bleachers would be ready for opening day, March 31.

The bad weather was causing delays and raising concerns. Some work could be done despite the weather, but as rainy day followed rainy day, it seemed less and less likely that there would be enough time for the ground to pack properly by opening day.

The construction contract for the grandstands and bleachers had been signed mid-January, but the start of actual work depended on the delivery of one million board feet of lumber. Once it arrived, the contractor was prepared to hire 300 carpenters and 100 laborers.

The rain finally stopped on January 28, but by then the cumulative effect of all the little delays made it doubtful that the stadium could open on time. The major concern was getting the playing surface in shape, which needed a long spell of dry weather. The next day the decision was made to open at Recreation Park—which hadn’t been torn down after the Giants and White Sox left. (Another opening day contingency plan had been to play at Oakland’s park.)

On March 20 Recreation Park was leased to the Olympic Club beginning May 1 for the two years remaining on the current lease.

The Examiner printed a photo of the field under construction on March 20, speculating that it would open on or about May 1. The seating capacity of 18,000 would be equally divided between the grandstand and bleachers. The grandstand would have actual seats—comfortable chairs—not benches as at Recreation Park. The stadium was designed to allow the addition of an upper deck, increasing the capacity to 23,000.

The continuing turf problem was finally resolved by replanting Rec Park’s turf on the new field. Ewing was adamant that there would never again be a grassless field in his stadium as there had been during the 1907 season.

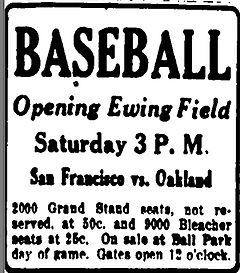

With an opening day dedication of the new stadium impossible, it was Ewing’s wish to celebrate the inaugural of the new park with a Saturday game against the Oakland Oaks—the new park’s other tenant. The earliest opportunity would be April 25, but that would have been during an Oaks’ home stand, creating the awkward situation of the Seals being the visitors at their own house warming party. The next possibility would be May 16 with the Seals as the home team.

On March 31 most of the 11,000 opening day fans at Recreation Park were unhappy. Some were unhappy because they were at Recreation Park and not at the new stadium. Some were unhappy because the weather was cold and miserable. Some were unhappy because the Seals lost their second opener in a row. But most were unhappy because Cal Ewing, who had no intention of serving alcohol at the new stadium, didn’t renew Recreation Park’s liquor license for its few remaining days. The notorious “booze cage” was booze-less. Not that there weren’t dozens of liquor emporia within a stone’s throw of Recreation Park to slake the thirst of the disgruntled fans and loosen their opinionated tongues. It was the principle. Men had an absolute right to drink at baseball games. Who did Ewing think he was?

And what did a booze-less new ballpark portend? On April 9 the official announcement of the opening date of the still-unnamed new park was made: May 16.

The new facility received its official name on May 4: Ewing Field. According to the Sporting Life (May 16, 1914, page 24 vol. 63 no. 11)

San Francisco’s new ballpark is to be known as Ewing Field. While it has been understood all along that J. Cal Ewing would be honored to that extent, Cal himself has been somewhat backward in permitting the suggestion. His associates, however, decided last week that no more fitting title could be selected. Ewing has been so long identified with baseball in San Francisco and formerly in Oakland that the title comes easily to hand.

The final game played at Recreation Park on May 15 was “the coldest sort of day the fans have seen in many an afternoon”. The final final score posted on the old park’s scoreboard was San Francisco 7, Oakland 4.

1914: THE TRUTH IS BETTER THAN FICTION

The thrust of this chapter is not just to bury some colorful (but untrue) tales, but to correct Ewing Field’s historical record by resurrecting true stories that have been lost and buried for a century.

Ewing Field hosted professional baseball for all of five months, yet some preposterous tales from that abbreviated season refuse to die. Two of the most fantastic and pervasive fables involve a player named Pete Daly setting a fire in the outfield for a couple of reasons, and another player, Elmer Zacher, becoming so disoriented and confused in the fog that the batboy had to be sent to retrieve him. However, no specific dates or details for these legends were ever provided because they never happened.

In 1914 there was no player in the Pacific Coast League named Pete Daly. In fact, in 1914 there was no player named Pete Daly playing baseball in any of the minor or major leagues. According to baseball-reference.com, in the entire history of organized baseball only one player named Pete Daly ever played professionally, and his career ran from 1884 to 1907. However, there was a player named Pete DalEy who had played in the Pacific Coast League: Thomas Francis (Pete) Daley. Baseball-reference.com records that Pete Daley played for the Los Angeles Angels from 1909 to 1912 and for the Vernon Tigers from 1916 to 1918. In 1914 Mr. Daley was in the major leagues playing for the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Yankees—certainly an ironclad alibi for the San Francisco arson charge.

The earliest mention of this old wives’ tale comes from the Los Angeles Times of April 11, 1937, nearly a quarter century after the alleged incident. According to the Times, the fire setting was done in protest of having to play under conditions that Mr. Daley felt to be unplayable. His protest, according to the Times, succeeded and the game was called. This legend was next reported in the June 18, 1938 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle, but this time Daley’s motivation was simply to keep warm on a cold day. If, in fact, Mr. Daley—or anyone for that matter—ever set a fire anywhere in Ewing Field, it was never reported in any of the game accounts of the San Francisco or Oakland newspapers.

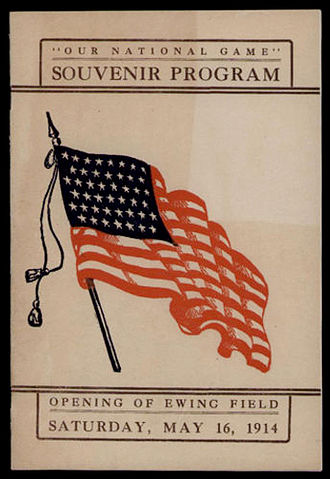

Opening day souvenir program with 45-star flag

from Mark Macrae collection

Elmer Zacher, the main character in the other too-good-to-be-true incident, did play in the PCL in 1914. But, as with Mr. Daley, there were no contemporary newspaper reports, or even subsequent newspaper reports, of Mr. Zacher (or anyone) needing rescue during a foggy game. The earliest mention of the search and rescue mission comes from the same Chronicle story that repeats the Pete Daley incendiary episode.

Nor was a game ever called because of fog. One historian/writer/blogger claims that it happened on June 6, 1914 when fog and rain made the field unplayable. Indeed, it was raining and it was foggy on that date, but the umpires ordered that the game go on. And it did. For the whole nine innings. In the end the Angels defeated the Oaks 10-9. The creator of this fairy tale doesn’t give a reference, but it has been repeated in books and on the Internet.

Another category of pseudo history seems intent on attributing hubristic motives to Cal Ewing while demeaning his planning. These claims accuse him of selfishly wanting his own ballpark because he was envious of the Oakland Oaks with its large, modern East Bay ballpark; or that he was tired of sharing Recreation Park with the Oaks, so he built his own park; or that Ewing Field was hastily built and poorly conceived.

There is no basis for the contention that Ewing was desirous of having his own ballpark. He had already had his share of them—three in fact: Idora Park and Freeman’s Park in Oakland when he owned the East Bay team, and Recreation Park. Nor, as another ill-informed critic pontificates, it wasn’t because he was tired of sharing Recreation Park with the Oaks. Ewing owned a majority of both clubs, and both the Oakland and San Francisco teams would continue with their long-established arrangement of playing games in both cities following the move to Ewing Field. Therefore, the building of Ewing Field had nothing to do with getting away from the Oaks or stadium envy. Simply, Ewing Field’s reason for existence was to give the Seals a place to play in San Francisco following Ed Walter’s betrayal and the expiration of the Rec Park lease in 1916.

The broad brush of innuendo has been liberally applied to give the misleading impression that a permanent dome of fog, wind and cold settled over Ewing Field on opening day and never moved, making every game a survival epic for fewer and fewer fans till finally the players were performing before an empty house. Yes! There was some positively beastly weather at Ewing Field. But there was also good, even beautiful weather. Both extremes, The Beauty and The Beast, were reported in the papers, but of course dishonestly emphasizing the negative and totally ignoring the positive makes for better legends, but sloppy history.

In terms of cause and effect, The Beast was definitely responsible for a drop in attendance that couldn’t be offset by The Beauty. However, other factors effected attendance but were never mentioned.

Nearly two months before the grand opening, the Chronicle reported on the new stadium’s location with this often-repeated observation:

The only possible drawback to the new location is the possibility of meeting with bad weather conditions. In the Mission the diamond play was in the warm belt, but out by Lone Mountain wind and fog may be experienced in the afternoon. The advantage of an up-to-date park, however, will do much to balance against those handicaps.

The Richmond District’s abysmal summer weather was no secret or recent phenomenon. In 1871 a Chronicle reporter visited Calvary Cemetery and described the conditions: “Strong summer winds sweep over the cemetery, requiring the skill and ingenuity of the carpenter to build fences and latticework to break their force.”

Despite the bombastic accusations of know-it-alls who accuse Ewing of being unaware or naïve regarding the climatic conditions around Lone Mountain, Ewing was in fact acutely aware. His 1912 plan for the Army Street stadium was to use the latest steel and concrete building materials. Ewing Field was constructed of wood because J. Cal felt it would not conduct the cold as readily as concrete and steel. He also oriented the field so that home plate was at the northeast corner of the parcel, thus allowing the sun to warm the grandstands and most of the bleachers. It’s significant that Ewing chose the Lone Mountain site over the St. Ignatius Stadium location, which was completely exposed to the wind-driven elements off the ocean.

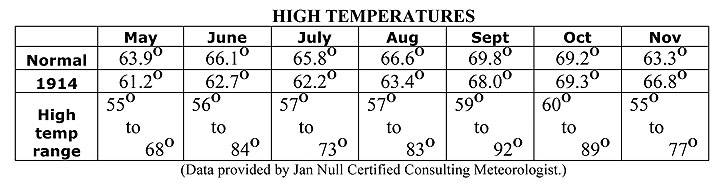

Finally, bear in mind that 1914 was an el niño year which had the following effect on San Francisco’s summer weather:

San Francisco’s official weather station was at Mission Dolores. No temperatures were ever reported for Ewing Field itself, thus all references to the weather conditions there were subjective.

On Opening Day, May 16, 1914, two intrepid young boys—best friends from the 1500 block of Grove Street—were about to see their first Seals game. For months 8-year-old Scotty and 9-year-old Pat had surveyed the construction of Ewing Field from the heights of Lone Mountain. On that special day the 25-cent admission was beyond their means, but not a barrier. There were other ways to get in. In his San Francisco Examiner “The Low Down” column of February 12, 1947, long-time sports writer Prescott Sullivan recalled how he and a young Edmund G. “Pat” Brown burrowed through the sand under the outfield fence and hid until the crowd arrived.

Shortly 18,000 spectators filled Ewing Field, Lone Mountain was thick with freeloaders, and two men circled above the spectacle in a tiny airplane. The day was especially windy all over San Francisco, but the big news, of course, was the wind at Ewing Field. On the ground a large floral sculpture in the shape of a good luck horseshoe was blown over by the wind. In the sky the small plane piloted by pioneer aviator Robert Fowler with his passenger, photographer Carl Wallen, “bobbed, bumped and bounded . . . sometimes diving in a way that dragged a gasp out of the crowd, and then it was flung skyward in a mad swirl as a dead leaf is tossed by a breeze.”

After being pushed as far as a mile from their objective and hurled and dropped hundreds of feet by the turbulence, Fowler managed to steady his delicate craft over the field long enough to drop a shower of roses and carnations on the celebration and allow Wallen to take aerial pictures of the largest ball park west of Chicago. Their missions accomplished, Fowler and Wallen made haste for the ground and shelter, leaving behind some 20,000 ground-bound, wind-buffeted spectators.

Once the sun passed behind Lone Mountain, the temperature (a high of 61 degrees at Mission Dolores) dropped faster than Fowler’s plane in an “air hole,” a cold wind whistled around Lone Mountain and shot down on the field and spectators, inspiring someone to suggest that “Icicle Field” might be a more appropriate name.

After the Oaks won 3-0, the bleacherites engaged in massive seat-cushion fights. Those who were arrested were fined $20.00 for disturbing the peace and threatened with jail for a second offense.

After the game 18,000 chilled fans were confronted with a long wait for streetcars, a never-ending source of frustration and complaint as much as the weather.

The next day was Sunday, so the afternoon portion of the double header was held at Ewing Field after San Francisco won the morning contest in Oakland. The Bulletin and the Call and Post commented on the bitter weather at the game, but softened the criticism by acknowledging that it had been cold all over town (57 degrees). Nonetheless, 10,000 fans were in attendance. After winning the afternoon game the Seals began a weeklong road trip, turning Ewing Field over to the Oakland Oaks. So much for Ewing building the stadium to get away from sharing his field with the Oaks.

By May 19 suggestions to raise the outfield fences to cut the wind were gaining voices, but, it was sadly conceded “there is no getting away from the fact that Ewing Field is located in the fog belt.”

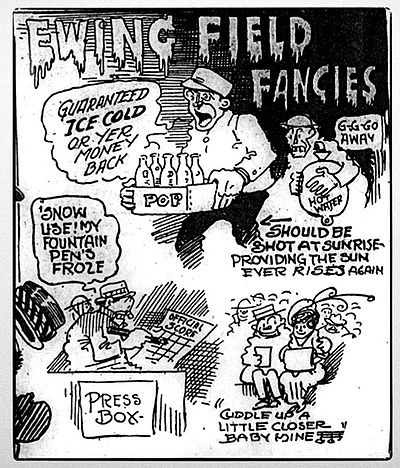

San Francisco Examiner May 25, 1914

The sports writers in the unheated press box quickly developed a survival strategy. A stadium vendor, Joe Derham, sold canned hot tamales. The writers would buy Joe’s hot cans and hold them to keep their hands warm. When the cans cooled, the writers would buy more hand warmers from Joe, but he refused to give them credit for returning the cold but unopened cans.

The players also came up with a creative solution to the hostile environment. A well-known liniment “with the heating power of a flock of furnaces” was liberally applied before games to keep the circulation going. The clubhouse was just as unforgiving as the press box, there being no stove for the warmth and comfort of the players.

Worst off were the umpires who were forced to dress in an unlighted, unventilated and unheated room deep beneath the grandstands that was too small to accommodate two arbiters at the same time.

While suggestions to build a 20-foot fence in right field were becoming demands, the Tribune offered that a few steam pipes in the grandstand or strategically placed warming stoves would help immensely. (Shades of Candlestick’s revolutionary radiant heating which never worked.) May 20 was the first day that was not cold, with descriptions ranging from “ideal for baseball and the fans enjoyed it” to “quite comfy” to “in comparison it was furnace-like” (65 degrees). Nonetheless, the call for higher fences intensified to a plea.

Ten days into Ewing Field’s life, the fans were given the opportunity to vote whether they wanted a 2:30 starting time or to keep the usual 3 o’clock start. An earlier starting time would lessen the exposure to the elements, which tended to deteriorate around 4 o’clock. Another argument for the earlier start was that the late afternoon conditions had a negative effect on the players, “manifested by sluggishness and an utter lack of pep” generally after the 7th inning. Their “sluggishness and lack of pep” caused the pace of the game to slow and contests which would be over in an hour and a half stretched out to two hours and longer. (All baseball games were played during the day. It would be more than 20 years before the first night games.)

On May 29, a day that was quite comfy (68 degrees) till the wind started to poke around Lone Mountain, Seal slugger Walter Cartwright hit the first home run at Ewing Field—an inside the park home run. Four homers were hit in the last game at Rec Park, but it would be July 7 before Ewing Field witnessed its fourth round tripper. For the entire year 15 homers were hit there, but none was an over the fence blast; they were either inside the park or “bounce” home runs that bounced into the seats—legitimate four baggers in 1914.

On Memorial Day weekend the Seals swept a double header from the Sacramento Wolves, so named in honor of their manager and part owner Harry Wolverton, to go into first place by 2½ games. Despite it being colder than opening day (58 degrees), “a good crowd” turned out.

Work finally began on a 20-foot extension to the right field fence on June 3 while voting on the starting time continued. Early reports were that the 2:30 start was ahead, but Ewing admonished his employees not to influence the votes. It was claimed that they were voting early and often as well as giving the patrons advice.

June 6 was the first of the truly extraordinary games played at Ewing Field lost to history. The papers could not agree whether it was foggy, misty, rainy, combinations of some, or all of the above. They all agreed, though, that conditions were unfit for playing but the umpires decreed the game would go on. The Chronicle suggested that each and every one of the 200 or so brave and hardy souls in attendance (“not counting the peanut vendors and cushion hustlers, but including two lady fans”) should be given a gold medal by the management. The Tribune was less charitable in counting the spectators: “the crowd was variously estimated as between nine and twelve, including the scorer”. Just as the papers couldn’t reach a consensus on the attendance, neither could they agree on when Elmer Zacher, Oaks center fielder, took his position holding an umbrella. According to the Tribune: “Zacher created a sensation in the top of the 3rd when he appeared in center field with an umbrella to keep off the rain and Umpire Hayes let him get away with it.”

The Examiner reported on Zacher’s novel defensive equipment: “It was in the second inning that E. Zacher went to work with an umbrella. The fans merely saw him disappearing into the distant haze with the umbrella in action, business side to the wetness.”

The Chronicle simply noted “Elmer Zacher in one inning pulled a bit of good-natured humor by showing up in center with an upraised umbrella. He used it all during the inning.”

Perhaps the oddest thing about the game was the Chronicle’s final sentence: “The weather was wet, but the air was warm, so that the fans attending the game weren’t the least bit uncomfortable.” This is the same date that a game was supposedly called because of fog, but clearly not so.

From opening day to the final game of the season, the two Bay Area baseball clubs played seven games a week with Monday off as a league travel day. Whether Seals or Oaks, the Bay Area schedule called for games to be played at Ewing Field on Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday afternoon, while Oakland hosted games on Thursday and Sunday morning. The savvy baseball fan of 1914 quickly learned how to enhance his baseball experience at Ewing Field by listening to the foghorns.

Stadium announcer at Philadelphia, 1914

courtesy Angus MacFarlane

The most important foghorn was Foghorn Murphy, the official voice of the Seals. In the days before sound amplification, leather-lunged men with huge megaphones made the important announcements at the games: batteries, line-ups, batters, etc., but not play-by-play.

Occasionally Foghorn would be driven around the city to boost the day’s upcoming game, but his regular job-site was Ewing Field.

In the days before radios and hourly weather reports, the fan had to know what to expect if he was planning to attend a game way out at Lone Mountain. If he worked downtown and the area was fogged in, he knew for certain that Ewing Field was foggier and it wouldn’t be worthwhile to go there. If it was clear at noontime as he began to make up his excuse for leaving work early, a glance westward gave him a sense of the conditions at Lone Mountain. If it was clear, chances were good he could enjoy a ball game. Low clouds meant he had a tough decision to make. If he saw the menacing fog bank to the west, he was better off working.

Once the fan made up his mind to go and found himself at Ewing Field listening to Foghorn Murphy announce the day’s lineups, there were other foghorns to heed. The maritime city of San Francisco had an array of foghorns along its shoreline, each with its own distinctive “call”. If the only foghorn our savvy fan heard during the game was Foghorn Murphy, all was well. But if he heard a 3-second blast every 27 seconds, he knew that fog had reached Mile Rock, 3½ miles to the west. A 2-second blast every 13 seconds signaled the fog’s arrival at Fort Point, 2.6 miles to the northwest. A single long blast every two minutes was a ship announcing its passage through the fog.

Hearing these maritime warnings, the savvy fan could decide whether to leave right away; stay a bit longer and see what happens with the game or the weather; or if it was a particularly exciting game, to tough it out to the end.

Ewing Field hosted “Charity Day” on June 9 featuring pre-game stunts and amusements to raise money for the city’s civic charities. The weather was the best of the year (65 degrees) and over 10,000 turned out to witness a pre-game contest between golfers and batters to see who could hit a ball farther. The golfers won hands down, easily sending their dimpled spheres far beyond the right field fence.

Only two batters managed to get a stitched sphere over the barrier. An attempt to catch a baseball dropped from 1,000 feet was unsuccessful because the dropper couldn’t get the ball to land in Ewing Field. During the game the tin charity donations boxes that were mounted throughout the stadium had to be removed because the sun’s reflection off the boxes blinded the fielders.

Three days later the PCL reported that 1914 was starting out as the poorest season for attendance since 1909. Los Angeles and Portland were far below their normal marks, while San Francisco, always the best city in the circuit, was disappointingly low. Weather throughout the league was blamed. The Examiner subsequently wrote that baseball conditions across the country were bad that season and the PCL was suffering as much as the other leagues.

The starting time vote ended with 2:30 winning overwhelmingly, but Ewing declared that weekday games would begin at 2:45. The first game under the new starting time would be the June 19 Oakland- San Francisco match.

The longest game of the year, a 3-hour, 14-inning affair between the Seals and Oaks, ended at 6 o’clock on June 16 when Oakland tallied the only score. The Chronicle marveled at how the clubs maintained such tight defensives “in the face of adverse conditions and much personal suffering by players and spectators from the intense cold” (60 degrees). The lone score came about “through a combination of thick fog and a couple of Seal misplays, and only the coldness marred what would otherwise go down as an enjoyable afternoon of our national pastime.”

The next day during another extra-inning game, the Lone Mountain contingent resorted to setting fires on the hillside to keep warm. (59 degrees).

Shortly afterwards someone in a position of authority felt that the 20-foot addition to the right field fence was insufficient, so an additional 26 feet was added to increase the wind barrier’s height to 50 feet.

Barely a month after Ewing Field opened, Cal Ewing exploded when it was suggested that he was considering returning to Recreation Park. He was quoted in the June 20 edition of the Bulletin “The story is utterly ridiculous.” Although acknowledging an attendance drop of about 15% over 1913, he insisted that San Francisco was much better off than the rest of the league. “Conditions at the new park are not a particle worse than they are all over the circuit.”

As if in support of Ewing’s assertion, the weather the next day “was all that could have been desired” (68 degrees). Not only did the sun force the fans to remove their coats and actually complain about the heat, it ignited fires in the grandstand. Peanut shells, bits of paper and other combustible debris that had collected in the cracks of the grandstand floor spontaneously ignited. Several small fires broke out, but a glass of water was enough to extinguish each small blaze. The Examiner memorialized June 26 as the most perfect day seen at Ewing Field. “It was warm and comfy and the fans enjoyed themselves immensely” (79 degrees). The weekend was even more beautiful (84 & 75 degrees), attracting thousands of fans. Without any bad weather to grumble about for a week, the papers turned their critical eyes on the still-abominable streetcar service.

The opening day program promised something that the streetcar companies never provided:

Located at the picturesque foot of Lone Mountain, the park is of easy access to people of all sections of the city. Direct car lines of the Municipal and United Railroads lead to the park, and our patrons are assured of much improved streetcar service. It will require only a matter of fifteen minutes to reach the park from Third and Market Streets and an additional five minutes’ ride from the ferry.

Ewing Field was out in the boondocks as far as the streetcar companies were concerned. With the dead greatly outnumbering the living, moving large numbers of people was not a transit priority “out there”. There were no north-south lines serving the field and only one viable east-west route served the ballpark—the Municipal Railway’s Geary line and its spur along Masonic. Five blocks to the south was the McAllister Street line and the Hayes Street line two blocks further away. Other east-west lines from downtown (where most of the game-bound crowd originated) ended five blocks to the west at Divisadero. Taking these lines necessitated either a long uphill walk to the field, or a long wait for multiple transfers.

Once conditions returned to “normal” at Lone Mountain (cold), the telegraph operators in the press boxes of other league cities resumed their favorite prank: wiring to the Ewing Field press box their local temperatures. The Tribune complained “It is annoying when you are freezing to hear of a place where it is 106 degrees in the shade.”

The 50-foot addition to the right field fence had two outcomes: it noticeably cut the wind, thus improving the conditions for the fans; but it also significantly limited the view from Lone Mountain, forcing the hillsiders to trek to the top of the mound. Even then their view took in only first and third bases and home plate.

One of the truly amazing aspects of Ewing Field’s history is that it took the Los Angeles press two months to ridicule it. On July 14 the Los Angeles Times chided

San Francisco’s New Baseball Park.

Every afternoon a fog rolls in from the Golden Gate just about the beginning of the second inning. The players become dim spectators through the mist and the few scattered spectators sit in the stands in a shivering misery. Nearly every game since the new park opened has been played in a bitter cold.

The day the article appeared in Los Angeles it was 73 degrees in San Francisco, making, for that day at least, a mockery of the Times’ mockery. The Times didn’t mention the poor transportation, but two days later the Call and Post echoed the constant complaint (now that the weather was improving) of “the poor service that is the rule these days.”

Another stretch of beautiful weather during the end of July and beginning of August brought out fans in numbers that the streetcars were still unable to handle. This time the Examiner editorialized:

The season’s best weather has prevailed at Ewing Field during the past week and there has been a big increase in attendance in consequence. But the car service has been wretched. Thousands of dollars were spent in building a spur track but it is seldom that a car is run over the line. After yesterday’s game the car accommodations were totally inadequate and complaints were many.

By July rumors were circulating that the Seals would return to Recreation Park. Ewing issued a flat denial: “now that we have the best baseball plant on the Pacific Coast, there isn’t a chance for our going back to the old ground or building a new baseball plant.”

On Friday and Sunday, August 14 and 16, baseball fans were the beneficiaries of good weather and good baseball between the Seals and Oaks. On Friday, what the Call and Post called ideal weather (64 degrees) brought out one of the best weekday crowds of the season for a well-played game that was marred only by a 9th inning come-from-behind Oakland victory. On Sunday “a monster gathering” assembled in 66-degree weather to witness the Seals triumph 7-3 to sweep the Sunday double header. They were now tied for second place with Venice, who would be in town the next week.

The battle for second place commenced on August 18. By the 6th inning the Seals were in full retreat, trailing 8-1. With the game all but lost, Seals Manager Del Howard replaced most of his starting players. One of those subs who found himself in left field was identified in the game accounts only as “Utschig”. The Seals’ nightmare had become Utschig’s dream come true.

Seventeen-year-old Irving “Irv” Utschig was a Lowell High School junior and baseball star. He was profiled in the school’s 1914 yearbook as a valuable leadoff man who led the team in batting and was the best outfielder in the high school league. How he came to be in a Seals uniform and on the Seals bench that day is a mystery.

Utschig’s defense during the game caught the attention of the sports scribes. The Examiner praised him: “The boy can get over a lot of ground and yank the ball prettily out of the air.” The Chronicle added, “Utschig, who is only a juvenile, appears to be a first class fielder. He had several difficult chances and handled them perfectly.” Irv’s batting, on the other hand, left a lot to be desired, as he struck out both times he came to the plate.

By appearing in this game young Irving forfeited his amateur status and was ineligible to play for Lowell his senior year. Was it worth it for one game? What baseball dreams did Irving have? Clearly he had talent and potential. How did the players respond to the “kid”? Was the plan for Irv to appear in just that one game, or did he suit up for other games without ever making it back onto the field? Utschig’s name never appeared in a box score of any kind again.

Sociologically, a baseball team is a closed or exclusive group with restricted membership. Normally a rookie would be “welcomed” into the group/team through a series of initiation rituals. One common ritual is to have drinks—a lot of drinks—with his teammates. In Irv’s case this would have been impractical for two reasons: his age and the dearth of drinking establishments around Ewing Field. In the necropolitan neighborhood around the ballpark, Prohibition had come six years early. There were none of the convenient watering holes that abounded near the previous Recreation Parks. The nearest oases in this desert were on Haight Street, ¾ mile to the south without any transportation; a couple could be found along Geary to the north; a scattering on Divisadero ½ mile to the east; and a sprinkling on Stanyan Street, a ½ mile hike on the western side of Lone Mountain. And worst of all, there was no booze cage at Ewing Field. J. Cal did not want the vile influence of alcohol to detract from the fans’ enjoyment of the game. In this regard he made a terrible miscalculation.

Simply put, there were no theres anywhere near Ewing Field to mix pre-game pleasure with business, or post-game business with pleasure, or just to prolong the baseball experience with friends in a cordial, convenient setting that was a ritual at Recreation Park. For the mostly-male fan base, the unavailability of the national beverage before, during and after the national pastime was as much a disincentive to trek all the way out to Lone Mountain as were the lack of streetcar service and the uncertain weather.

The last game of August featured the league’s two worst teams on one of the worst days of the year. Nonetheless, 1,100 stalwart fans showed up. The beginning of September usually marked the arrival of summer in San Francisco. Sure enough, the first game of the month was “all that could be desired” (65 degrees), attracting a good turnout of fans who were rewarded with a Seals victory that put them in a tie for second place with the Los Angeles Angels. The next day’s “ultra pleasant weather” (61 degrees) brought out another large weekday crowd that “sat through the session in absolute comfort”. The Chronicle optimistically predicted, “It looks as if weather conditions are changing for the better.”

On September 6, Ewing Field became “home” to a third team. All season long the Sacramento Wolves were beset with financial problems which finally resulted in the team’s collapse at the end of August. To preserve the integrity of the league, the PCL took control of the 5th place Wolves and moved them to San Francisco where they were renamed the Missions.

The Beauty was in her full glory now. On September 9 the third largest crowd of the season sat coatless for the entire game in 82-degree heat. The next day was the hottest day of the year—92 degrees—and once again it was coats off for another large crowd.

The September 15 game between the Missions and Seals was another truly wonderful story that has been buried for a hundred years. It was the debut game for the former Sacramento Wolves as the home team at Ewing Field. Somewhere the official temperature was 60 degrees. The Call and Post prosaically noted: “During the late innings the fog was so thick that the outfielders were lost to view.”

The umpires briefly halted the game, but did NOT cancel it. The Chronicle declared the game to be the foggiest ever played at Ewing Field, noting that it wasn’t a cold fog “but it made up in denseness what it otherwise lacked.” Several hits were made because the outfielders were unable to see the ball.

Examiner sports writer Al Joy added the possibly apocryphal story of the bat boys who, according to Mr. Joy, “When a ball was hit to the far distances, ran out and told the fielders to expect it. Then they ran back and told the umpire what had become of it.”

For the next two weeks the average high temperature was 67 degrees, including October 4’s 74 degrees that brought out 12,000 fans for a Seals-Oaks game.

The Examiner reported warm (64 degrees) and pleasant conditions at the start of the Seals-Mission game on October 7. Then it started to rain and the Mission players expressed their displeasure with the umpire’s decision to continue the game by deliberately annoying him with loud noises from their bench. The umpire, Billy Phyle, repeatedly ordered them to stop but they continued. By the third inning Umpire Phyle had had enough and ejected all the non-playing Missions. Which was exactly what they wanted. As the 10 players happily made for the clubhouse, they laughed in the umpire’s face.

On October 9, 8,000 baseball fans chose to stand in front of the Chronicle building on Mission Street rather than to watch the Seals and Missions play in perfect (68 degrees) baseball weather at Ewing Field. What attracted them was a huge electric scoreboard that flashed instantaneous play-by-play returns of the first game of the 1914 World Series in Philadelphia where the A’s were facing Boston’s “Miracle Braves”. Braves manager George Stallings had played for Oakland, Stockton, and San Jose in the 1880s and 90s in the old California League and was fondly recalled by many old-time baseball fans. The Chronicle’s display was free. The Gaiety Theatre on O’Farrell and Powell charged twenty-five cents.

The Beauty’s visit lasted through the end of the PCL season. For the month of October the average high temperature was 69 degrees, a fact the Call and Post noted: “The weather at the new grounds during the past couple of weeks has been ideal.”

The PCL season ended with a double header on Sunday, October 25. In the morning game, Seals pitcher Skeeter Fanning threw a no-hitter against the Portland Beavers in Oakland. In the afternoon game, played in 77-degree heat at Ewing Field, the Seals completed the sweep of the pennant winners with a 13-1 victory.

Four days later the Examiner railed against The Beauty’s fickleness:

Ewing Field, after being frostbitten and icicle-hung for many long, weary months, is basking in the balmy sunshine of Indian summer right now when nobody cares what sort of weather prevails.

When there were ball games Ewing Field shivered and shook and masked its distant gardens in the ocean mists. Now when the only excitement holding forth is the undisturbed growing of the grass, Ewing Field is as warm as a piece of toast hot off the gas.

And the magnates, who swore at the fog and wind of the good old summer time, now railing at the perversity of fate, swear more heartily at the delicious sunshine of the fall.

It is a funny old world, isn’t it?

Although the PCL season was over, baseball had not abandoned Ewing Field. On November 3, the national pastime returned in the persons of American and National League barnstormers who would spend a week in San Francisco. The first game was played before 8,000 fascinated fans in beautiful 74-degree weather. The Chronicle marveled: “it was actually hot with no fog, wind or other disagreeable features”. For their entire stay, the major leaguers enjoyed San Francisco’s best weather (the average high was 73 degrees.), but were disappointed to not experience The Beast that they had heard so much about.

Before leaving for Southern California, a member of the major league entourage praised Ewing Field: “There are not many major league parks that have anything on this field.” The major league tourists returned to play on November 21 and 22 before sailing to Hawaii. On the final day their wish came true: they came face to face with The Beast at its worst.

The Examiner exulted: “The field lived up to its reputation to the very end. Never before did the fog overhang from above in such massive chunks.”

The Chronicle straightforwardly described it: “Fog, undiluted and foreboding was the main feature at Ewing Field . . . There were times when the most you could see of the fielders was now and then a streak as they dashed helplessly after a ball of whose direction they had no idea.”

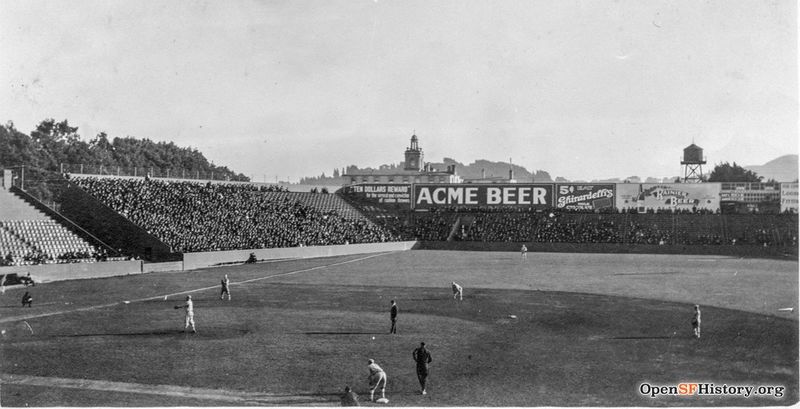

The San Francisco Seals playing at Ewing Field, 1914.

Photo: courtesy OpenSFHistory.org, wnp27.0604

The blinding fog was also sound absorbing. Unable to see or hear, Giants outfielder George Burns had no idea that a ball had been hit his way until it smacked him on his foot. The Cardinals’ Cozy Dolan waved a white handkerchief from his centerfield position to remind his teammates where he was. The American Leaguers found it too terrifying to stand at bat against Grover Cleveland Alexander, not knowing if he could see them, and not seeing his fastballs until the final instant. The National Leaguers left the field 13-2 victors, and 1914 was history.

1913-1915: SEASONS OF THE WOLF (#2)

Within a year of leaving Oakland for The Big Apple (America’s largest city) with its Hilltop Park and the Yankees, Harry Wolverton found himself in Sacramento (the PCL’s smallest city) with its Buffalo Park and the Senators.

While he was in New York, Baseball Magazine, the sport’s leading monthly publication, called Harry a brainy and capable leader who suffered through a season-long series of misfortunes, accidents and disasters unparalleled by any other club in the American League. Under the circumstances, Baseball Magazine concluded, Harry did as well as anyone could have done. The New York press and Yankee fans, who normally were highly critical of anything short of perfection, did not blame Wolverton for the club’s 50-102 season.

Since rejoining the PCL in 1909, the Senators never had a winning season, finishing 4th twice and last twice. Believing that Harry’s year in New York was an aberration and confident that the Grey Wolf could duplicate his 1910 miracle in Oakland, the Sacramento magnates gave him the largest paycheck in the Pacific Coast League to bring the capital city a winning team for the 1913 season. He began by replacing almost the entire 1912 team.

But the miracle was slow in coming. The Senators opened the 1913 season at home against Harry’s former team and defending PCL champs Oakland Oaks. Harry’s boys lost 3 of 4 to begin the season in last place. His first visit to Oakland as a rival manager was over Memorial Day weekend. Oakland had a different team from the one he led in 1910 and 1911 and new management, but the fans were the same and 11,000 of them showed their adoration for Harry at the Sunday morning game. The Bay Area press affectionately referred to the Senators as the “Wolves” in tribute to the Grey Wolf.

Slowly Harry’s managerial genius began to produce results. On July 10 the Wolves reached a pinnacle skeptics had believed impossible: a winning record mid-way through the season. Three days later they defeated the Seals to reach the lofty heights of 2nd place.

On July 16 the Chronicle resurrected a figure from Harry’s past: Ed Walter, his former boss during his Oakland Oak days, and bane of the Pacific Coast League and J. Cal Ewing. There was a rumor that the Sacramento club was for sale and that Walter and Harry Wolverton were prospective buyers.

The season came down to the final week with second place up for grabs between Sacramento and the Venice Tigers. The Wolves’ final series was against the pennant-winning Portland Beavers at Sacramento. Before the first game Harry and the Beaver’s ace pitcher Bill James went toe-to-toe behind the bleachers, the culmination of a feud that originated last year when Harry was with the Yankees and James was with Cleveland. A right from the 24-year old James to Harry’s 40-year old head gashed his eye and sent Fighting Harry down for the count. It also broke James’ wrist and ended his season.

The Wolves finished in second place with a 107-94 record compared with their 1912 record of 73-121.

WOLVES TO GO UNDER HAMMER was the Call’s lead on October 25. The accompanying story related that Sacramento owner Jack Atkin wanted to sell his club to move to Europe to race horses. Financially, thanks mainly to Harry’s brilliance, the club had done well, making a profit of $11,000 for the season.

On November 11, Harry and Lloyd Jacobs bought the team for $24,000. A little over a year after being fired by the Yankees, Harry was a baseball magnate, a dream he had had since his Oakland days.

He once offered to buy the Oaks for $48,000, but the owners turned him down. If the Oakland deal had gone through, how might have San Francisco baseball history been different?

The new owner of the Wolves kept only four 1913 starters and two pitchers for the new season. Nonetheless, the team started off much better on the field than the previous year. Things were not looking good in the box office, however. The novelty of having a winning team playing exciting baseball seemed to have worn off on the Wolves’ meager fan base of 50,000—about 1/10 of San Francisco’s. Matters reached a critical point when the Wolves lost 20 of 28 games in August and the few fans who attended the games stopped altogether. The team had been hurting financially all season.

Harry acknowledged losing over $1,000 per week, but this was the club’s death knell.

At the end of August the PCL Directors called an emergency meeting to address the Sacramento problem and decided that the league should take control of the club. In the best interest of baseball, the franchise would be moved to San Francisco where it would finish out the last eight weeks of the season. At that time Cal Ewing made the innocent and sensible suggested that the new team be named the Missions to avoid confusion over having two teams with the designation of San Francisco.

Also making sports page headlines once again was Ed Walter. He had been entirely out of baseball since selling his Oakland stock in January, but events back east made him a loose cannon in San Francisco baseball. In 1914 a third major league—the Federal League—arose to compete with the two existing major leagues. The new major league wanted to establish its own minor league system. One of the leagues would be on the west coast with San Francisco as one of the cities. Walter, who still held the 20-year lease on Recreation Park, had been approached by the Federals to head the Federal’s San Francisco club which would play at Recreation Park.

On September 4 the Bulletin suggested that Recreation Park might be the home of the Missions in 1915. Citing an unconfirmed rumor, Recreation Park’s current lease would be turned over to Wolverton and Jacobs for the 1915 season. Noting that Ed Walter and Harry Wolverton were good friends, the Bulletin stretched credibility by hinting that Walter would help his old friend by giving Wolverton the 20-year lease. Thus, the two San Francisco-based clubs, the Seals and the Missions, would play at two separate venues.

The Tribune went one step beyond the Bulletin’s speculation by reporting that Wolverton had already taken over not only the current lease at Rec Park, but Walter’s lease as well. Walter denied giving the lease to his friend, but he didn’t deny that there was a deal pending. “I have always had a warm personal regard for Harry Wolverton and am anxious to do anything I can for his welfare. As yet there has been no assignment of the lease. Beyond that I would rather not discuss the matter.”

The Call and Post went even farther, citing on “a well-founded rumor” that Recreation Park would be the home to at least one baseball club before the current season was over.

Sacramento was officially dropped as a PCL city on September 6. The adoption of Ewing’s off the cuff suggestion that the orphaned team be called the Mission Wolves was taken as a sure sign that the club would have a home in the Mission i.e. Recreation Park.

Harry Wolverton dismissed such talk as pipe dreams. It didn’t take long, however, for the rumors to take root and spread. Even the Seals players were speaking knowingly that the team would be playing in Recreation Park “by next week”. Given that three of the Pacific Coast League’s six clubs were now situated in two Bay Area cities with, possibly, three playing venues, the combinations and permutations of who would play where were topics of deep discussion.

The wild card in Bay Area baseball was the last place Oakland Oaks. With two teams in San Francisco for at least the remainder of the 1914 season, Oakland would realize its long-held dream of seven games a week in the East Bay. This would be a real test of Oakland’s ability to support its team.

For the next week plans for an elaborate ceremony to officially christen the Missions replaced the discussion of where they would play. The event was scheduled for the Seals-Mission game of Saturday, September 19 at Ewing Field. Presiding would be Mayor Sunny Jim Rolph, not only as the representative of San Francisco, but also as a resident of the Mission District. However, the ceremonies were postponed until the Missions returned from a two-week road trip because Harry Wolverton had supposedly obtained an option from Ed Walter on Recreation Park’s 20-year lease. It was believed by many that this would somehow enable the Missions to move into Recreation Park under the current lease. The two weeks was considered necessary to return the grounds to ball-playing condition.

Wolverton would neither confirm nor deny any of this, which, according to the Bulletin “can be taken as prima facie evidence that such a move is contemplated.” The Tribune hinted to its readers if the Missions moved to Recreation Park and out-drew the Seals at Ewing Field, the Seals would follow them back to the Mission.

The PCL Directors were to meet on September 19 to discuss the fate of the Missions, but the decision was put over to October 6. Still unresolved were the outstanding debts Wolverton and Jacobs had incurred from the PCL to keep the team afloat during the season. Cal Ewing had personally advanced them $10,000. If the debts weren’t paid by October 6, the team would be forfeited to the league.

The October 6 meeting was put over to the end of the season. On October 27 the PCL Directors, as expected, assumed control of the Wolves. Also coming out of the meeting was the unexpected news that Ewing and his partner Frank Ish were anxious to sell the Seals. Undoubtedly the ordeal of the past year led Ewing to cash in his 1912 promise to his wife to retire after the 1915 season a year early.

Within five days, five offers had been made for the club, including one from Harry Wolverton. The front-runner, according to the Chronicle, was Los Angeles Angels owner Henry “Hen” Berry. His purchase of the Seals was contingent on selling his current club. What the price for the Seals would be was not certain, but knowledgeable sources estimated between $175,000 and $225,000.

Berry and his associates made it abundantly clear that they wanted to return to the Mission District. To that end, they planned to meet with Ed Walter regarding the Recreation Park lease. He hinted that if he did buy the club he would go back to Valencia Street for the 1915 season, since Ewing’s lease ran till May 1916. After that he had no definite plans, though he proposed either leasing or buying new grounds. He was in favor of buying new grounds, but if that didn’t work out, he was quoted, “If we use Recreation Park, we figure on getting additional property on 15th Street and placing the grandstand there.” This was exactly what Cal Ewing tried but failed to do in 1907.

In the meeting with Ed Walter, Berry learned that Harry Wolverton held an option on the 20-year lease till January 1. That didn’t bother Berry who figured that he could return to Rec Park in 1915 and by the time the lease expired in May 1916, a new ballpark could be built.

Once again San Francisco baseball fans were hearing familiar words, this time from Henry Berry: “Several propositions have been submitted for a new park and we are now looking them over. San Francisco fans can rest assured that we will find available grounds. Two sites south of Market are being considered, either of which would be more desirable than Rec Park.”

Wolverton’s plans to secure backing to buy the Seals didn’t materialize, but he had five aces up his sleeve with his 20-year lease option.

At the end of November, while Berry was in Southern California, it was “discovered” that the Olympic Club held the current lease to Rec Park through May 1, 1916. “It will certainly create one grand mix-up if we can’t get Recreation Park to play on next year” one of Berry’s associates said. “This was the first time the Olympic Club hold on the lease came up in the purchase negotiations. We will not go back to Ewing Field and if we cannot get the Valencia Street grounds, there will be no place to play, for it is too late to build a new park. We could arrange new quarters by 1916, but not by next year. If we cannot get Recreation Park the deal is off.”

The Olympic Club magnanimously surrendered the lease, and on December 5 all the details were ironed out to conclude the largest deal in minor league history. Rumors set the price at between $200,000 and $250,000.

On December 30, 1914, Harry Wolverton and Hen Barry met. We’ll never know what was discussed, but the outcome was a brilliant business, baseball, and public relations coup. The Seals finally obtained the 20-year lease on Recreation Park, Harry Wolverton received the largest managerial contract in PCL history to manage the Seals for the next three years, and the fans had a popular manager with a fighting spirit.

“I think that I have reason to congratulate myself,” said Mr. Berry. “From the way people talk all over the city I guess that I've picked the right man for the job, and I'm glad that the worry of naming a manager is over.”

The final worry was officially put to rest on January 31 when the Judson Estate Company turned over the 20-year lease on Recreation Park, formerly held by Ed Walter, to Henry Berry, clearing the way for the Seals to make long range plans for Recreation Park. All the way through 1936 if need be.

Harry was given carte blanche to assemble a team to his liking. Wearing his third Bay Area uniform, the Grey Wolf and the Seals were an immediate success on the field, but were poor box office draws as the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition attracted would-be baseball fans away from Recreation Park.

The team won the 1915 pennant against a surprising challenge from the Salt Lake City Bees, the reconstituted 1914 Wolves of Sacramento and the Missions who had been relocated to Salt Lake City.