Decade of Political Conflict 1901-1911

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

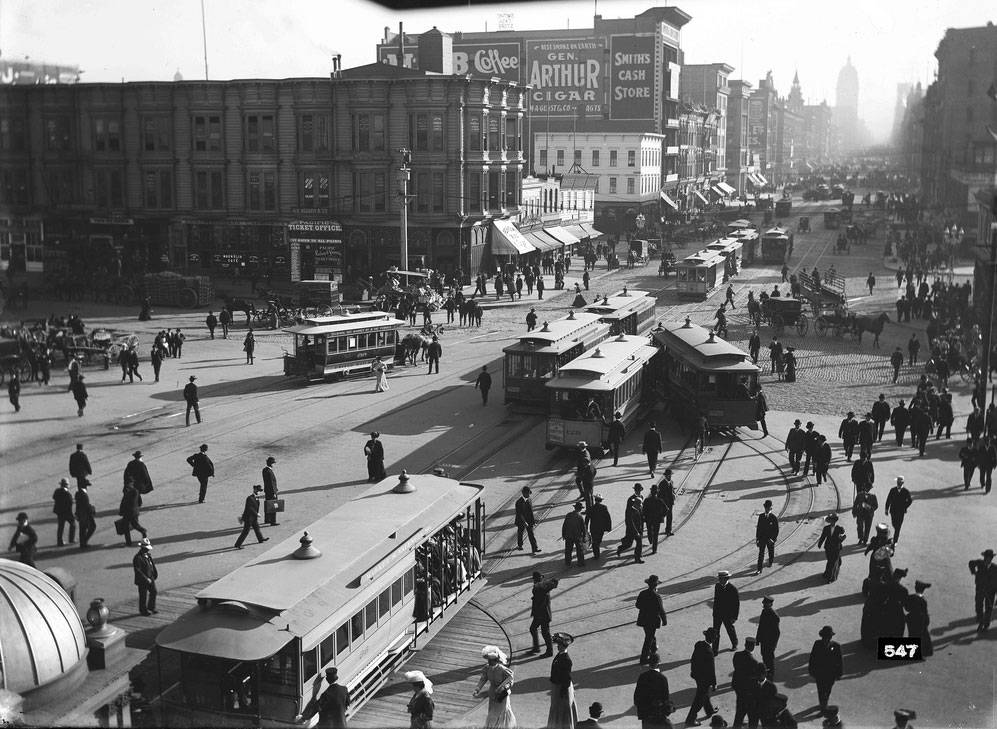

Cable cars cluster at the Ferry Building loop at the foot of Market Street, August 23, 1905.

Photo: SFMTA U00547

The Phelan Administration

Mayor James Phelan put together his policy recommendations for municipal projects with the cooperation of the Merchants' Association.(52) During his first campaign in 1896, he had argued that San Francisco should be "the capital of an empire,” and in the 1899 Democratic Party municipal platform he wrote that the “great and varied resources of the Pacific Coast behind us and the vast ocean before us point unerringly to the greatness of San Francisco.”(53) Phelan stressed the need to “act with confidence.” The Merchants’ Association applauded the mayor’s sentiments and spurred him on to more aggressive leadership on behalf of the city’s commercial priorities. “The fact is,” argued former Merchants’ Association director Herbert E. Law, “there is nothing inevitable about . . . the city’s growth, about density, about future greatness, about natural center and inevitable control of commerce.”

There has never been an organization in this city approximating the present organization of the Merchants’ Association. There has never been a time when the merchants were in so close union, so strongly cemented together, son single in their purpose, and so resolute as they have shown themselves to be during the past year [1898] . . . but in comparison with the possibilities, the effort has been but that of a child.

The organized business community needed “a careful leader, who will train every force in the direction it is needed” and “give San Francisco a great future.”(54)

Phelan promoted San Francisco business from his position as head of municipal government while arguing that the necessary spending would benefit the entire population by increasing population and tourism. Terrence McDonald's study of city expenditures shows an "across-the-board increase in expenditure over that of the machine [1883-1892] period.” Placing a higher priority on accountability and efficiency than on fiscal conservatism and budgetary stringency, the Phelan administration, in consultation with organized business, "sought to bend the power of politics to their own tasks, broadly conceived, in line with a new notion of urban political economy.”(55) A similar spirit informed the administration's approach to bonded indebtedness. With encouragement and urging from the neighborhood improvement associations and the Merchants' Association, the mayor proposed bond issues for a new sewer system, city hospital, city hall, park extensions, schools, and port improvements. In 1899, voters approved an issue for the sewer system, a new hospital, seventeen schools, and two new parks. Although taxpayer suits blocked some and the courts invalidated others, Phelan eventually secured approval to increase the city's total indebtedness from $186,000 in 1897 to $11,025,000 in 1901.(56)

The San Francisco Labor Council differed with Phelan on the need for public improvement bonds, just as it had earlier disagreed with his advocacy of the new charter. The mayor nonetheless attracted substantial support among the city's working-class voters by helping to raise money for striking miners, by endorsing a demonstration against the use of federal troops against strikers in Idaho, and by participating in Labor Day parades. "Mr. Phelan has made a good mayor," according to the Voice of Labor; "San Francisco has had few if any that were better." Even when the city's trade unions took advantage of the post-1897 return of prosperity to demand union recognition and the closed shop—novel measures considerably beyond the usual proposals for "pure and simple" improvements in wages, hours, and conditions—Phelan expressed sympathy by adopting a "hands-off" policy.(57)

Phelan's attempts to draw together both business and labor behind a program of municipal reform and city development, a strategy he had successfully pursued as the leader of the 1897-1898 phase of the charter campaign, worked until the summer of 1901. Then, during a bitter two month-long strike, which pitted a recently organized and militantly anti-union Employers' Association against a City Front Federation representing some sixteen thousand teamsters and waterfront workers, Phelan found himself forced to side with the employers. Now, instead of praising the mayor, the labor newspapers carried articles alleging that Phelan had advised workers to return to their jobs if they wanted to avoid being clubbed. Instead of passing out prizes during a Labor Day parade, the mayor presided over an administration in which police officers protected strikebreakers. The evidence suggests that Phelan tried to arbitrate, but employers refused to cooperate. The mayor announced his intention to preserve order and refused to defend what he considered the destruction of private property by strikers. He refused to intervene or countermand the orders of his police commissioner. The commissioner, George Newhall, who served as president of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, ordered officers to clear strikers off the streets along the waterfront, guard drivers of nonunion wagons, and disperse picket lines. The Iron Trades Council, involved in a separate strike, argued that Phelan and his administrators had lent "their official aid to assist a small wealthy combination of capitalists to override and tyrannize every citizen of the city" and had consequently violated their oaths to use their office for the good of all San Franciscans. Their solution: use the next municipal election to vote for a city administration made up solely of union members.(58)

The Union Labor Party

Mayor Phelan had announced that he would not seek reelection even before the strike by teamsters escalated into the waterfront conflict, but the pervasive perception among working-class voters that both the mayor and the Democratic party had betrayed them stimulated the organization of a labor party during the summer. Members of unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labor, delegates to the County Labor Council, and Socialist Labor party activists founded the Union Labor party. Political broker Abe Ruef emerged as the power behind the scenes by the time of the nominating convention in the fall. A University of California graduate and a lawyer from the city's Jewish mercantile elite, Ruef had aspirations for national political prominence. Frustrated in his attempt to unseat "regular" Republican leaders with his own Republican Primary League in the August 1901 primary elections, Ruef nonetheless had faith in the concept of coalition politics that Phelan and the Merchants' Association had used so successfully in the charter campaign. Walton Bean has pointed out that Ruef's strategy consisted in choosing directors for the Republican Primary League from "every religion and creed, and from labor, capital, merchant, practical politician, and professional man. Each was to be given equal prominence."(59)

Three weeks after he had failed in his bid to take over the city's Republican party, Ruef and several labor associates from the Republican Primary League successfully introduced what became the official platform of the Union Labor party. Sensing a leadership vacuum in the movement to create a municipal labor party, Ruef moved quickly and wrote what he described as a platform "true to every principle of labor, yet conservative." One historian has described the document as "a masterpiece of equivocation,” but nonetheless it fit nicely into the coalition strategy. Ruef also successfully proposed his friend and one-time business associate Eugene Schmitz as the Union Labor party nominee for mayor. Schmitz, a native San Franciscan, could likewise appeal to a multiethnic and interclass coalition because he was a Catholic homeowner, with both German and Irish roots, and besides being president of the Musicians' Union, he also had experience as a businessman and employer.(60)

Despite the tradition of political independence among trade unionists that fostered a distrust of either partisan endorsements or labor parties, Andrew Furuseth, head of the Sailor's Union of the Pacific, overcame his long-standing opposition to "a class government." "I found," he said, "that we had a class government already and inasmuch as we are going to have a class government, I most emphatically prefer a working-class government." Both the Labor Council and the Building Trades Council, however, refused to endorse the Union Labor party. The Building Trades Council, with some vehemence, described the party on election eve as a "stench in the nostrils of all law-abiding citizens."(61)

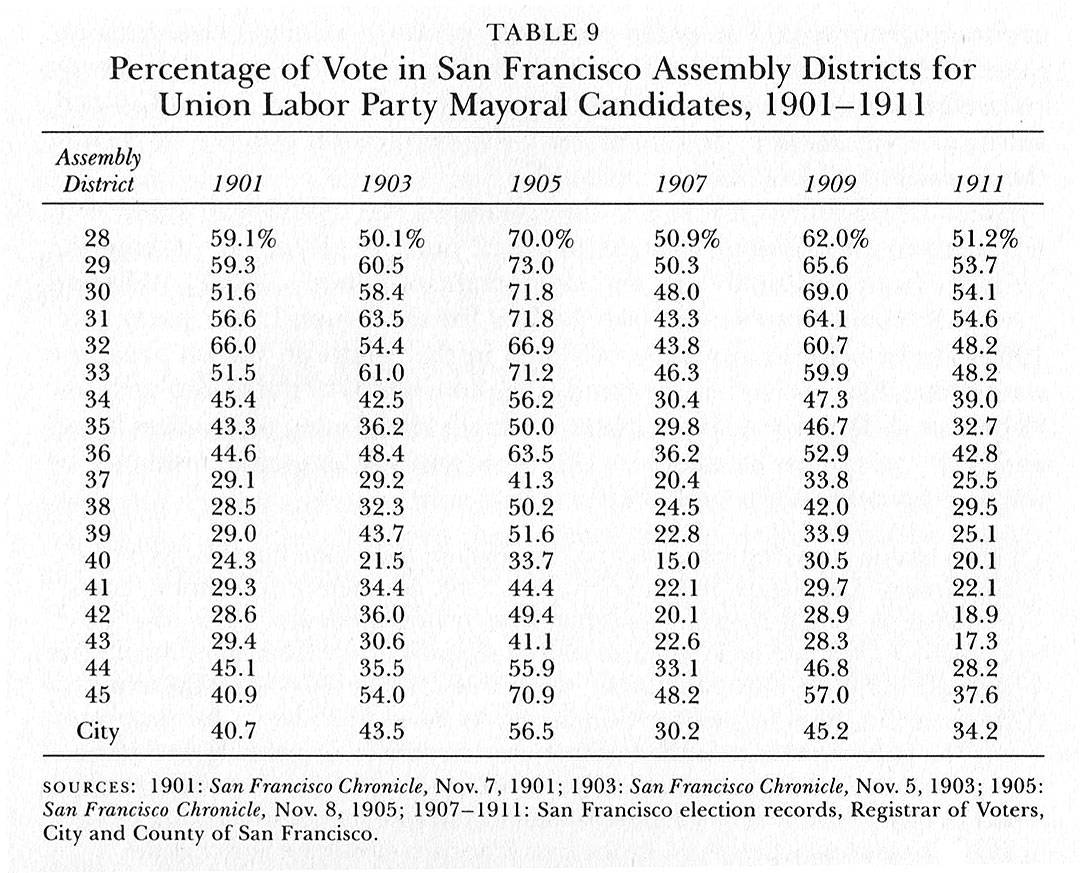

Steven Erie and Jules Tygiel have analyzed the voters who sided with Furuseth to give Schmitz a victory with 42 percent of the vote, taking the plurality from his Republican and Democratic opponents, Asa R. Wells and Joseph S. Tobin, respectively (see Table 9 for the Union Labor party vote, 1901-1911). Schmitz ran especially well in the South of Market area, the waterfront districts, and in the family neighborhoods of the skilled artisans. "The votes," Tygiel concludes, "were distinctly distributed along class lines," and "the correlation between the ULP vote and working-class residence by ward was an extremely high, .84."

The election provided, in a sense, a referendum regarding the policies of the Employers' Association and the right of unions, not merely to organize, but to establish the closed shop. In choosing Schmitz over Wells and Tobin, the San Francisco electorate had demonstrated its support of the labor movement. The second, and more important issue, was one of who should control the city government, labor or capital. As indicated by Furuseth's reasons for support ing the party, workingmen had come to realize that "class government" did exist in San Francisco, and that elections were a battle over which class would achieve power. The extreme polarization of the vote demonstrates that these issues were clearly perceived by the San Francisco electorate and that the struggle was fought and decided along class lines.(62)

While Schmitz received only a third of the votes in the well-to-do areas of the city that had given the charter its greatest support, his opponents granted him a period of grace and adopted a wait-and-see attitude. Mayor Phelan charged that the Employers' Association had erred in adopting an intransigent position during the waterfront conflict. He also affirmed the right of working-class voters to take their protest to the polls and concluded that the election had been "a splendid object lesson in popular government." City attorney Franklin K. Lane predicted that Schmitz would "surprise the decent moneyed people and anger the laboring people with his conservatism." Neither Schmitz and his supporters nor Phelan and Lane realized it at the time, but the ability of the Union Labor party to elect a mayor and three of the eighteen supervisors ushered in a period of partisan instability and political turmoil that lasted until November 1911.(63)

Decade of Conflict

This decade of conflict, dramatically punctuated by the earthquake and fire of 1906, divided itself into four phases. From January 1902 to the end of 1905, the Union Labor party made its debut, and the Schmitz administration adopted a pro-labor stance. In April 1902 the Carmen's Union struck against the United Railroads, blocked streetcar tracks, and jammed downtown traffic. The general manager tried to intimidate the strikers by hiring armed guards to ride the streetcars, but Mayor Schmitz refused to issue permits to carry weapons. The daily newspapers likewise supported the strikers, as did many local employers, and the union made a favorable settlement after only a week on the picket lines. Schmitz kept his seat in the 1903 election, but the Union Labor party managed to elect only two super visors that year, one of whom also had the Republican party nomination. By the end of 1905, several developments had begun that would shape the party's later history. Phelan, chagrined at a boycott against a labor party issue of municipal bonds in the national financial market, and his friend and business associate Rudolph Spreckels, had begun to show interest in the muckraking exposes of graft in the Schmitz administration that Fremont Older included in the San Francisco Bulletin. As managing editor of the paper, Older had increased its circulation and made himself something of a guardian of the city's morality by printing sensational stories of protection provided to prostitutes and gamblers by the Union Labor party administration. At the same time, however, the Citizens' Alliance had launched a particularly aggressive open-shop campaign (without the sympathy of Phelan and more pragmatic capitalists), a campaign that convinced Patrick McCarthy (head of the Building Trades Council) to give official support to the party as a way to ensure the survival of the skilled trades unions.(64)

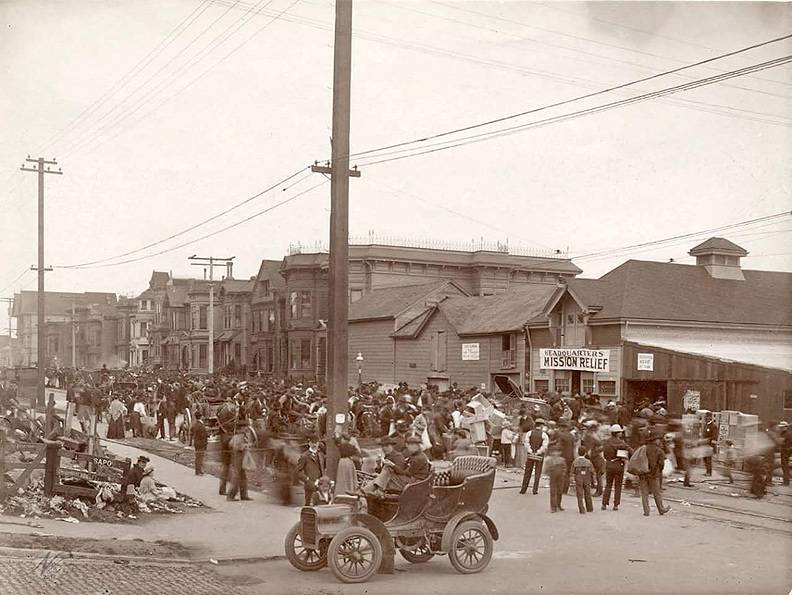

Mission earthquake relief center, 1906.

Photo: Private Collector

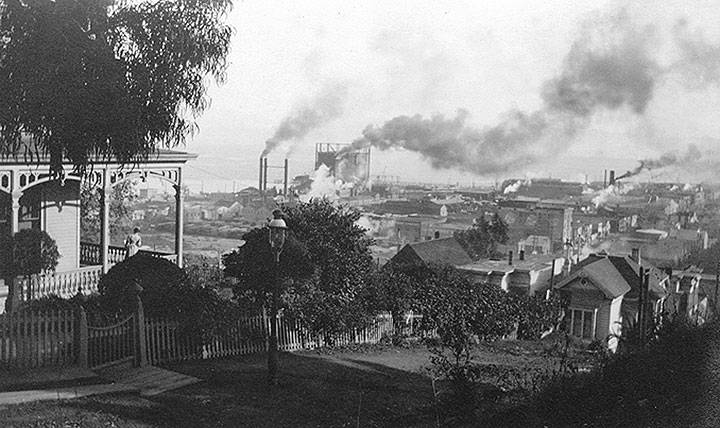

Ruins of North Beach, post 1906 earthquake and fire

Photo: Private Collector

The second phase of the decade of conflict lasted from the end of 1906 to the end of 1907. The aggressive head of the antiunion Citizens' Alliance made the open shop a political issue in an incendiary speech during the 1905 campaign, and McCarthy's endorsement brought to the labor party even more votes from the city's primary-sector working class. For working class voters, a vote for the party now meant a vote for a city administration dedicated to the defense of labor against the open shop and its consequences. Mayor Schmitz and every labor party candidate, including the entire Board of Supervisors, took their offices in early 1906 with large majorities behind them. Schmitz maintained his policy of refusing police protection to strikebreakers or to the property of employers when he refused to increase police forces on the waterfront during the lockout against the Sailors' Union of the Pacific in 1906. The newly elected supervisors, however, regarded themselves as independent of organized labor, as well as impervious to the reputed stature of Abe Ruef as their "boss." A series of careless deals involving payments to the new supervisors by businessmen hungry for franchises allowed another segment of the business community (led by Phelan and Spreckels) to expose the Union Labor party, bring its officials to trial, and remove them from office. In the middle of 1907, a plan to nominate a replacement mayor by means of a joint convention of the Labor Council, Building Trades Council, Merchants' Association, Chamber of Commerce, Board of Trade, Real Estate Board, and Merchants' Exchange broke down. Three members of the "graft prosecution" team then chose Dr. Edward R. Taylor, a member of the city's social elite, as interim mayor. The three-man team then required the eighteen members of the Board of Supervisors to make Taylor's position official by electing him. Then those who had confessed to bribery resigned, at which point the new mayor appointed replacements. The new Board of Supervisors was thereby purged of representatives from organizations of the working class. Patrick McCarthy, free from any association with the disgraced government, in an attempt to preserve what was left of the labor party, ran as the party's candidate in November 1907 against Taylor. But Taylor, running on a nonpartisan "Good Government League" ticket supported by Phelan, Spreckels, and those members of the business community anxious to bury the Union Labor party, kept his office.(65)

The two years between the election of Taylor in 1907 and McCarthy's successful second campaign as the Union Labor party candidate in 1909 constitute the third phase of this period. As the sensationalist exposes of 1906 and 1907 hardened into predictable and tedious legal moves and countermoves in 1908 and 1909, the city's newspaper editors lost interest in the moral crusade. Businessmen Patrick Calhoun, Thornwell Mullally, Frank G. Drum, John Martin, W. I. Brobeck, and others were indicted for bribery, and the socially prominent business elite members of the Pacific Union and Bohemian clubs lost patience with muckraking and the graft prosecution when the spotlight turned in their direction. The leaders of the city's various trade associations and booster organizations complained of lost business from customers who disliked the climate of uncertainty. McCarthy's victory in 1909 rested on a coalition between businessmen opposed to the continuation of the graft trials and dependable regular supporters of the labor party in the working-class neighborhoods. In the words of James Walsh: "Ethnic-labor politicians joined Nob Hill capitalists to forge a new coalition against the prosecutors who were still trying to convict the bribe-giving [business] executives.” Using a typical "business unionism" appeal grounded in the concept of harmony between capital and labor, McCarthy promised to bring to city hall an administration dedicated to classless, conservative, businesslike government.(66)

McCarthy proved a disappointment to the Merchants' Association, the Chamber of Commerce, and other backers from the business community. Always uneasy about his independent base of support and concerned that his live-and-let-live philosophy regarding saloons, gambling, and prostitution would compromise their campaign for an international exposition, business leaders dropped him for a more predictable candidate. The San Francisco Labor Council had endorsed the third-party philosophy of the Union Labor party, and some of its leaders had consistently opposed McCarthy; they also refused to support his candidacy in 1911.(67) The years 1910 and 1911, therefore, make up the fourth and final phase of a decade of political turmoil marked by the rise and fall of the Union Labor party. By this time, San Francisco, like cities all over the country, had reached the limits of "the discovery that business corrupts politics.” As Richard McCormick has shown, muckrakers like Fremont Older of the Bulletin filled their pages with "facts and revelations,” but "these writings were also dangerously devoid of effective solutions." In California, as elsewhere, the "passions of 1905-06 were primarily expressed in state, rather than local or national politics," and usually "the policy consequences were more favorable to large business interests than local solutions would have been."

Criticism of business influence in government continued to be a staple of political rhetoric throughout the Progressive era, but it ceased to have the intensity it did in 1905-06. In place of the burning attack on corruption, politicians offered advanced progressive programs, including further regulation and election-law reforms. The deep concern with business corruption of politics and government thus waned.(68)

The demise of the San Francisco graft prosecution, particularly the deflection of blame away from the corporations that had offered the bribes, including Pacific Gas and Electric, Pacific Telephone, and the United Railroads, had come about partly because the Merchants' Association and the heads of the city's largest banks waged a decisive campaign to turn discussion about municipal politics away from issues of class conflict and business graft toward issues of city development and economic progress. The high point of the graft trials coincided with both the city's recovery from the earthquake and fire and the nation's recovery from the banking panic of 1907 that created a widespread clamor for corporate regulation. San Francisco financial institutions suffered less than some others, but the sobering experience tended to draw the city's bankers into self-conscious organization just as it did elsewhere.(69) The first step involved creating a favorable public image for business. The editor of the new journal Coast Banker described in October 1908 the need to counteract the "proposition that is generally in the minds of the public" that "the public-service corporation is the enemy of the public." Corporations "should be protected from rash and ill-considered action on the part of the people."(70)

View of North Beach from Leavenworth and Francisco, c. 1910.

Photo: provenance unknown

John A. Britton, president of San Francisco Gas and Electric Corporation and first vice-president of Pacific Gas and Electric, admitted that "the original sins of the corporations themselves" were "equivalent to the action of get-rich quick concerns." At the same time, he criticized "the present attitude of the press" because "it will rarely, except in its advertising columns for pay, give the corporation side of any argument." Britton urged the organized business community to adopt "a new method of treating the public" in order to restore corporations "to the favor in which they were once held."(71) Frank Anderson, president of the Bank of California, urged both the press and the students and faculty in a University of California speech to remember that although "the communal conscience has changed" and "some things regarded right or proper twenty years ago are frowned upon today," it would be "better even that abuses should continue for a time longer than that they should be corrected by injustice and by the infliction of hardships upon those who are wholly innocent." Calling for cooperation among all segments of the community interested in progress, Anderson praised his listeners for "whatever high and honorable ideals you may have formed .... You need have no apprehension that they will be scorned in the business world or that you will have to put them away to win success."(72)

Anderson, Britton, and the Coast Banker all advocated regulatory legislation as an antidote to the kinds of business graft that Fremont Older and his colleagues had uncovered in the course of the graft prosecution. "Regulation," according to Britton, "is needed for protection" from a sensationalist press and vote-hungry politicians.(73) Like the advocates of charter revision in the 1890s, the supporters of regulatory legislation during the next decade favored administrative solutions and executive powers of government over legislative bodies. They trusted expertise and centralized decision making and regarded both voters and elected legislators with grave suspicion. "What," asked Britton in April 1909, "can a body of men chosen from the masses, know in the generally farcical investigations made, of the detail of a business that calls for the highest skill in finance and engineering." His preferred mode of accountability involved administrative structures of government. Legislatures "have neither time, patience, or opportunity to legislate for such control as is needed, but should only be empowered to delegate to an executive body especially organized for that purpose, such regulation and control after a calm, and unbiased presentment of the case as each issue becomes involved."(74)

Brittan's position as president of San Francisco Gas and Electric and first vice-president of Pacific Gas and Electric gave him a direct interest in the question of the regulation of San Francisco corporations. He also maintained an active interest in city development and served as a director of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. Like so many executives of San Francisco's largest corporations, Britton saw no conflict of interest between the progress of his firm and the progress of his city. Once the proper regulatory commissions began their work, the public ire would dissipate, and Britton urged newspaper editors to stop making "political heat" and instead "engage in a campaign to better and uplift."(75) Russell Lowry, assistant cashier of the American National Bank, reminded San Franciscans that they owed their economic well-being to the fact that it was the banks and corporations that had made their city the Pacific Coast's leading metropolis.

A remarkable feature of this condition is that the accumulation of wealth has not been alone in the hands of a few rich men, but the stream has been widely diffused and distributed among all classes and occupations. As the rich have become richer, the poor have also become richer, and there are few cities in the world of its size so free from slums and tenements as San Francisco; few where the workers have been so uniformly prosperous, so able to live in comfort with a minimum of hard work and put by a little something against the day of adversity.(76)

The Merchants' Association, convinced that San Francisco would lose its premier position if it did not modernize port facilities, recruit new residents, attract conventions, strengthen architectural safety standards, and adopt professional accounting procedures for city government, moved aggressively in 1910 and 1911 to regain the leadership role it had played during the charter campaign in 1894-1898. M. H. Robbins,Jr., an engineer trained at Yale University who served as Pacific Coast manager of the Otis Elevator Company, assumed the presidency of the organization in June 1910. Possibly influenced by the model provided by Boston, where the Merchants' Association had merged with the Chamber of Commerce the preceding year, Robbins gave direction to the "growing feeling in the community that more effective work could be done by the various commercial organizations in San Francisco if they were consolidated into one large and powerful association."(77)

Between mid-1910 and the end of 1911 when a reorganized San Francisco Chamber of Commerce began life after a merger of the Merchants' Association, Downtown Association, Merchants' Exchange, and Chamber of Commerce, Robbins and the Merchants' Association initiated a wide ranging series of proposals for San Francisco urban development. These included a ten-year local improvement bond issue, charter amendments allowing the city to construct the Twin Peaks and Stockton Street tunnels, and a plan for more efficient accounting systems for the municipal government. The association also helped organize a Convention League, which secured twenty-three conventions for the city in 1911, and it began several projects designed to increase access to and movement on the southern waterfront. "We aim," said Robbins at the formal inauguration of the new Chamber of Commerce, "to establish by the influence and work of a united citizenship the power necessary to San Francisco's advancement, at a rate commensurate with her greatness. It requires only sufficient local patriotism to substitute order for disorder; and reason, common sense and action for negligence, indifference, and inertia."(78)

Determined to rid San Francisco's reputation of the smell of scandal that remained from the years of Union Labor party administrations and graft investigations, the organized business community moved into electoral politics. Convinced that intense partisan conflicts produced instability, they supported a successful charter amendment in November 1910 that established nonpartisan municipal elections. Besides prohibiting party affiliations of candidates on the ballot, the measure strengthened the role of the chief executive by extending the mayor's term of office from two to four years. The amendment also specified that any candidate who received a majority of votes at the primary would automatically be elected. When Congress announced at the end of January 1911 that San Francisco had defeated New Orleans and other rivals in the competition to host the 1915 international exposition, organized business pulled its resources together and planned a campaign to elect a businessman-mayor who would guarantee political stability and social harmony by appealing to as many segments of the electorate as possible.(79)

The Mayoral Campaign of 1911

In April 1911, attorney Henry U. Brandenstein and twenty businessmen and professionals, members of both parties, organized a Municipal Conference for the purpose of nominating James Rolph, Jr., for mayor. They also drew up a slate for all city elective offices and pledged to carry out an aggressive campaign. Except for six attorneys and three physicians, the members of the Municipal Conference were leading businessmen, twelve rated listings in the Blue Book, three served as Chamber of Commerce officers, and four belonged to the Merchants' Association. Half of the group had at least one parent who had been an immigrant.(80)

Rolph had seemed an ideal candidate for mayor as early as 1909 when both the Republican County Committee and the Municipal League of Republican Clubs had unsuccessfully solicited him as a nominee. Two friends, Gavin McNab, long-time Democratic party strategist, and Republican Matt Sullivan, law partner of recently elected Governor Hiram Johnson and a Johnson appointee as chief justice of the state supreme court, kept up the pressure on Rolph to run for the office. McNab and Sullivan had good reason to think that Rolph might be able to create the kind of coalition that Phelan had attracted in 1896 and 1898. Like three of every four San Francisco men, he was the son of immigrants. Like the majority of wage earners, he had grown up in a working-class district, and like those workers who voted in largest numbers, his father (a bank clerk) had achieved respectability by means of steady work and devotion to his family. Rolph himself remained in the Mission District of his youth all his life, despite his well publicized self-made journey from newsboy to millionaire.(81)

Owner of both a shipping firm and a bank, Rolph served three terms as president of the Merchants' Exchange and twice as a trustee of the Chamber of Commerce. He boosted home manufactures as president of the Mission Promotion Association, and he played a leading role in the creation of the reorganized Chamber of Commerce. Employer of both seamen and shipyard workers, Rolph served as president of the Shipowners' Association and helped negotiate the first formal contract with the Sailors' Union of the Pacific. He resigned from the Shipowners' Association when it supported the open shop during the waterfront strike of 1906.(82)

If his business record and his sympathy with the principle of collective bargaining attracted both labor and capital, Rolph 's civic work endeared him to those San Franciscans who believed that future growth and development depended upon a progressive alliance between business and government. After the earthquake and fire, Rolph established the Mission Relief Association, with his home as headquarters, and he successfully fed tens of thousands of homeless people. He served as an officer of the Portola Festival of 1909, and he played an active role on the Committee of Six that successfully lobbied to have San Francisco picked as the site of the Panama Pacific International Exposition.(83)

When he announced, "I am not a politician," upon accepting the Municipal Conference nomination, Rolph gave notice that his appeal to voters would be based on a call for civic unity by a man who stood above partisan loyalties. His battle cry, as the Examiner called it, dramatized this unity theme: "I am for all the people."(84) The Municipal Conference platform, endorsed by both parties, constituted a straightforward extension of the reform Democratic principles of the Phelan campaigns of 1896 and 1898, the doctrines of the charter reformers, and the lessons learned by organized business from the political strife of the Union Labor party period. Rolph pledged to repudiate patronage and extend a rigorously enforced civil service, especially in the fire, police, and school departments. Liquor licensing would be reformed in order to end the alleged favoritism of the McCarthy administration. Not surprisingly, the platform included municipal ownership of utilities, Hetch Hetchy water for the city, the purchase of the Spring Valley Water Company, modernization and extension of the streetcar system, and harbor improvements—all measures of long-standing interest to both business and labor advocates of urban development. Rolph favored complete freedom for unions to organize, and he pledged himself to a policy of noninterference in conflicts between management and labor.(85)

Carole Hicke has described how in all of Rolph's speeches "the event upon which he was able to hang all of his principles was the coming of the Exposition."

Did the city need new harbor facilities? The Exposition provided the rationale, for many visitors would arrive by water. Was public transportation a problem? The need must be answered, the system improved and expanded, to prepare the city for the Fair tourists. Was industrial conflict liable to become serious? A moratorium on all such conflict must be declared until the Exposition was over.(86)

The strategy of referring to the exposition served to dramatize Rolph's conviction, and that of his sponsors, that the interests of the city as a whole took precedence over those of any particular district, neighborhood, or faction. In this respect, Rolph and his supporters aligned themselves with what Samuel Hays has called the "cosmopolitan" point of view, or as Rolph himself put it: "I will be the mayor for the whole city, and not the mayor for any particular section. I will try to wipe out all dividing lines on the map of San Francisco."(87) To working-class audiences, Rolph appeared as "just plain Jim Rolph of the Mission, your neighbor. I believe in labor unions and have long been a friend of labor." To national-origin groups, like the Scandinavian American Political Club, Rolph could say: "I feel at home with Scandinavian people. I am in the shipping business and have come in contact with men of Norway and Sweden." His message to the organized business community reiterated his dedication to administrative government:

I am aware that the principal usefulness of the Mayor consists in the work which he may be able to do as the executive head of its business affairs, looking upon the city not so much as an integral part of the state, but as a business corporation of which the citizens are the responsible shareholders.(88)

Rolph refused to make accusations against the incumbent mayor, but his chief campaign aides launched a blistering attack on McCarthy, who, they claimed, had ignored the needs of the various interest groups in the city and "whose only political creed is to perpetuate himself in power or climb to higher achievement." Rolph's endorsers and speechmakers included several influential leaders of the city's labor movement who preferred him both because of his repudiation of the open shop during the 1906 waterfront strike and because of their long-standing aversion to Patrick McCarthy. Andrew Furuseth, head of the Sailors' Union of the Pacific, once again abstained from his rule against involvement in electoral politics and made a pro-Rolph speech just before election day. Walter Macarthur spoke frequently on Rolph's behalf, as did James De Succa of the Iron Molders' Union, James H. Roxburg of the Print Pressmen, and Edward J. Kirwin, who had served on the Union Labor party county committee. The labor leaders drove to and from Rolph rallies in a large touring car, capable of carrying a dozen people, that reporters dubbed "the Union Labor special."(89)

None of the charges made against McCarthy could be proven, and the similarities between his platform and Rolph's made it hard for voters to distinguish between their policy positions . McCarthy came out in favor of woman suffrage and said he wanted San Francisco to be a closed-shop city, and these forthright stands may have lost him some support. McCarthy suffered more from the loss of backing from several organized groups, including the 3,100-member P. H . McCarthy Businessmen's Association that had supported him in 1909. Rolph, on the other hand, attracted the endorsements of the Democratic and Republican parties, the Non-Partisan Voters League, and the San Francisco Civic League.(90) An "Irish-American Club," announcing that "we do not support candidates for reasons of race or religion," campaigned for Rolph under the leadership of George A. Connelly. Connelly argued that the key issue in the campaign should be the fact that the "demoralized state of our affairs is fast destroying the world confidence San Francisco has richly earned," and Rolph was the "man to restore our credit and insure an era of prosperity."(91) A group called the Municipal Conference Campaign Committee, composed of three hundred men, organized the rallies and publicity for Rolph. The group included Edward Taylor, the former mayor; A. H. Giannini, brother of the head of the Bank of Italy; Adolph Spreckels; Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.; and Francis V. Keesling, wealthy attorney and vice-president of the West Coast Life Insurance Company; as well as Walter Macarthur and a handful of labor leaders. "They were mainly upper and middle class, middle-aged business men and professionals. Ethnicity of the group reflected the San Francisco population's characteristics, with a somewhat higher percentage of northern Europeans."(92)

The steady growth of Rolph's coalition between April and September 1911 signified the gradual dissolution of McCarthy's political base. The mayor refused to acknowledge the weakness of his position, however, and ten days before the election he could still proclaim: "Wherever I go, I am acclaimed with cheers. It will be a landslide, pure and simple, for the entire Union Labor ticket." McCarthy could not have been more mistaken. Rolph received 47,427 votes to McCarthy's 27,067 on September 26. The Socialist party candidate took 3,893.(93) Once again, as in the vote on the reform charter in 1898 and every mayoralty election from 1901 to 1909, the vote in 1911 showed the importance of both class and ethnicity. As Hicke has aptly put it, although the "most significant characteristic that can be identified city-wide was whether the voter was foreign born or native born," the “more transitory, possibly unskilled working class tended to vote for McCarthy, while the more stable, family-oriented workers tended to vote for Rolph.”(94)

The editor of the Coast Banker made his own analysis of the vote int eh October issue of the journal. Rolph owed his nearly two-to-one victory to the fact that he “stood for common sense, decency and protection of personal and property rights.” But “a large part of the more intelligent men of San Francisco, by reason of their living in the suburbs, do not vote in the city proper. It is roughly estimated,” he wrote, “that had Oakland, San Rafael and other suburbs voting power in San Francisco the vote in favor of the people’s candidate, Mr. Rolph, would have been over three and one-half to one.”

The greatest good that will come to San Francisco by reason of the results of the election is the rehabilitation of the reputation of the city, which throughout the entire world had practically been lost. Naturally . . . property values have been materially strengthened by the election.”(95)

By the time Rolph took office in January 1912, Governor Hiram Johnson and the state legislature of 1911 had begun the passage of pro-labor legislation that would earn it a reputation for progressivism among the San Francisco electorate. Labor Council activists now placed their support behind the progressive program, just as some of them stood behind the Rolph candidacy, and the city’s rank-and-file working-class voters followed their lead. As the South of Market electorate became a smaller proportion of the working-class vote, these voters also moved to the right politically, demonstrating by their votes for both progressive statewide candidates and for Mayor Rolph their belief in the possibility of a municipal government “for all the people.”

Notes

52. Phelan pointed this out in his inaugural address; see Chronicle, Jan. 5, 1897.

53. Phelan, quoted in Kahn, Imperial San Francisco, pp. 62, 66.

54. Merchants' Association Review (Jan. 1899):2.

55. McDonald, "Urban Development;' pp. 197,198,203, Table 4.12.

56. Ibid., p. 204; Kahn, Imperial San Francisco, p. 69.

57. Quoted in Jules Tygiel, "The Union Labor Party of San Francisco: A Reappraisal;' typescript, 1979, pp. 6-7. See also Jules Tygiel, "'Where Unionism Holds Undisputed Sway': A Reappraisal of San Francisco's Union Labor Party," California History 62 (Fall 1983):196-215, Tables 1 and 2.

58. Tygiel, "Union Labor Party," p. 201; Bean, Boss Ruef's San Francisco, pp. 12-17; Franklin Hichborn, "The System" as Uncovered by the San Francisco Graft Prosecution (San Francisco, 1915), p. 12.

59. Bean, Boss Ruef's San Francisco, pp. 9-10. :1

60. Tygiel, "Union Labor Party," p. 11; Bean, Boss Ruef's San Francisco, p. 20.

61. Quoted in Tygiel, "Union Labor Party," pp. 13-14, 15-16.

62. Ibid., pp. 16-18, esp. p. 18. Table 9 describes the ways in which the city's assembly districts remained more or less polarized over the Union Labor party between 1901 and 1911. With only three exceptions in four of the six elections, the party's mayoral candidates consistently received higher percentages of the vote than the citywide figures in the nine districts (28-36) where working-class voters pre dominated. By contrast, eight of the nine middle- and upper-class districts gave the party substantially less than the citywide percentage in two of the six elections, and seven of the nine did so in four of the six elections.

63. Bean, Boss Ruef's San Francisco, p. 27.

64. Ibid., pp. 40-54, 61, 75-77; Knight, Industrial Relations, pp. 120-121.

65. For details, see Bean, Boss Ruef's San Francisco, pp. 153-267. See also Walsh, "Abe Ruef Was No Boss," pp. 3-16.

66. Walsh, "Abe Ruef Was No Boss," p. 12.

67. Ibid.

68. Richard L. McCormick, "The Discovery That Business Corrupts Politics: A Reappraisal of the Origins of Progressivism," American Historical Review 86 (April 1981):272-273.

69. On the national scene, see Robert H. Wiebe, Businessmen and Reform: A Study of the Progressive Movement (Chicago, 1968), p. 68.

70. Coast Banker, Nov. 1908, p. 5; ibid., Oct. 1908, p. 5.

71. Ibid., April 1909, p. 153.

72. Ibid., March 1911, p. 158.

73. Ibid., April 1909, p. 154.

74. Ibid.

75. Ibid.

76. Coast Banker, special issue for the American Bankers' Association meeting in Los Angeles, Oct. 3-7, 1910, p. 132.

77. San Francisco Merchants' Association, Seventeenth Annual Review: A Year of Civic Work (San Francisco, 1911), p. 13; Richard Hume Werking, "Bureaucrats, Businessmen, and Foreign Trade: The Origins of the United States Chamber of Commerce," Business History Review 52 (Autumn 1978):322-341.

78. Chamber of Commerce Journal, Dec. 1911, p. I. For the activities of the Merchants' Association, see the monthly issues of its Review during 1910 and 1911, especially the article "Year's Work of Merchants' Association Covers a Wide Field of City Betterment," July 1911, pp. 5-6. As in 1896-1898, the association joined forces with the neighborhood improvement associations.

79. Young, San Francisco, 2:919-926; Carole Hicke, "The 1911 Campaign of James Rolph, Jr., Mayor of All the People;' master's thesis, San Francisco State University, 1978, pp. 11-12.

80. Hicke, "1911 Campaign," p. 21. 81. Ibid., pp. 12-13.

82. Ibid., p. 20.

83. Ibid., pp. 15-16.

84. Rolph, quoted in ibid., pp. 22, 24.

85. Chronicle, Aug. 13, 1911.

86. Hicke, "1911 Campaign;' pp. 23-24.

87. Examiner, Aug. 25, 1911. For the Hays argument, see Samuel P. Hays, "Political Parties and the Community-Society Continuum;' in The American Party Systems: Stages of Political Development, ed. William N. Chambers and Walter D. Burnham (New York, 1967), pp. 152-181.

88. Rolph, quoted in Hicke, "1911 Campaign;' pp. 25, 27.

89. Ibid., pp. 28, 31.

90. Ibid., pp. 41, 54, 59.

91. Connelly, quoted in ibid., p. 58.

92. Ibid., pp. 65-66.

93. Ibid., pp. 67, 69.

94. Ibid., pp. 75-76. See also Table 3, note 45, in Tygiel, "Union Labor Party;' where Tygiel points out: "Since class and ethnic origins overlapped so greatly ... it is difficult to distinguish between the two and they were probably mutually reinforcing factors:'

95. Coast Banker, Oct. 1911, p. 251.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 7 “Progressive Politics, 1893-1911”