Chinatown in Hunters' Point?

Historical Essay

by Ralph Henn, © San Francisco Magazine, Inc., 1970, republished with permission of author

Chinatown ruins 1906.

Photo: Opensfhistory wnp27.4964

For a tourist attraction Chinatown is ideally situated, near the downtown shopping district and the City's hotels. But what if the racial composition of the east side of Nob Hill were largely black? Far fetched? Perhaps not. After all, Hunters Point almost became Chinatown.

In 1906, the destruction of Chinatown by fire was considered a great blessing of the Earthquake. Many felt it should have burned long before. Said the Overland Monthly, "Fire has reclaimed to civilization and cleanliness the Chinese ghetto, and no Chinatown will be permitted in the borders of the city.... it seems as though a divine wisdom directed the range of the seismic horror and the range of the fire god. Wisely, the worst was cleared away with the best."

Before the Earthquake, Chinatown, even then a major tourist attraction, competed for notoriety with the neighboring Barbary Coast. Chinatown abounded in opium dens and gambling and about 1000 slave prostitutes worked the area. Most Chinese, however, were quite respectably kept busy in sweat shops, as souvenir shop proprietors, laundrymen and comparatively well paid servants. Many lived in airless cellars that sheltered up to 500 people; about 25,000 Chinese lived in 12 square blocks. (Today there are close to 50,000 packed into the same area.)

Then the Fire.

The Chinese scattered in all directions—to the waterfront, up Nob and Russian Hills, to Union Square and to Portsmouth Square where they clashed with the Italians fleeing North Beach, fighting for open space. Three days after the quake, the last of the fires—having burned 520 blocks at a rate of $6 million property damage an hour—was under control. Four days later the City was told that all the remaining Chinese—many already segregated into a camp in North Beach—would be "collected" and placed in the Fontana fruit canning warehouses (where Fontana Towers now stand) east of Fort Mason until a camp could be built on the four sand-duned blocks bounded by Octavia, Franklin, Chestnut and Bay Streets, just south of the fort. Tents to accommodate 10,000 had been secured and U.S. engineers were laying out lines of the camp.

But then a problem dawned on the Committee of Fifty for Relief and its Subcommittee on Relocating the Chinese, which had been formed to prevent the Chinese from recongregating on their former, extremely valuable site. What if they liked this new location at the foot of Van Ness Avenue, just north of one of San Francisco's major residential districts? And what if the area's property owners found it profitable to house the Orientals? It could be tough to get them out later. As the Chronicle saw the sentiment of the City, the complete destruction of Chinatown had "given rise to a hope that the Chinese quarter may now be established in some location far removed from the center of town." This didn't mean the foot of Van Ness; it meant almost out of the City—Hunters Point. Some people wanted immediate "gathering" of the Chinese there, fearfully skipping the temporary Fort Mason camp.

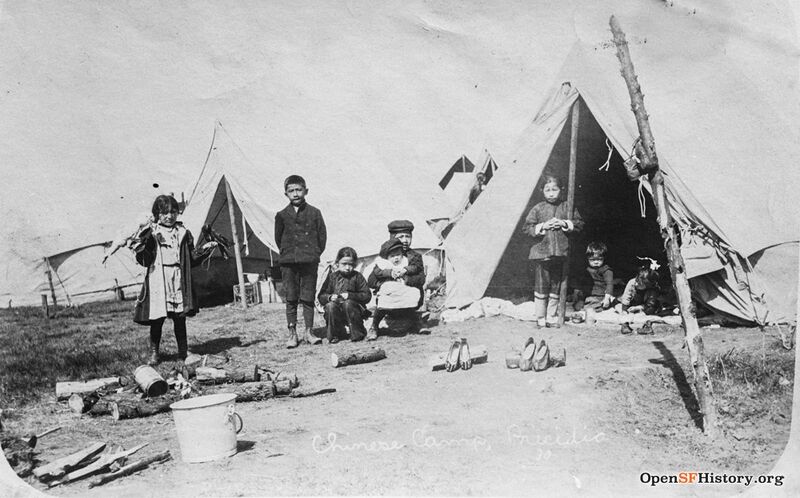

Presidio 1906 Chinese Camp Presidio 30.

Photo: Opensfhistory wnp37.10116

But then what if the Chinese ended up migrating out off the City, just across the line into San Mateo County? While the subcommittee wished to eliminate Chinatown from the center of the City, it didn't want to chance losing property and poll taxes. Deserted Colma had already been considered and eliminated as a possible site.

Fear of losing money, as it is wont to do, was greater than the fear of not being able to dislodge the Chinese from the Fort Mason location later, so that's where they were gathered. But two days after the Chinese had been gathered and encamped, someone figured out how to get them away from Fort Mason, too: Move them to the Presidio golf links. Those who still favored permanently locating Chinatown in Hunters Point or "some equally remote locality" saw little chance of the Chinese establishing themselves permanently on a golf course.

Problem solved. For one day. Enter a delegation of neighboring residents and property owners, complaining to the military that "the summer zephyrs would blow the odors of Chinatown into their front doors."

A new location was hurriedly secured on the military parade grounds above Fort Point, where all that remained of Chinatown was installed under martial law before noon of the same day. An ideal location, albeit temporary—remote from any white neighborhoods, surrounded on two sides by water and too far removed for spill-over into a neighboring county.

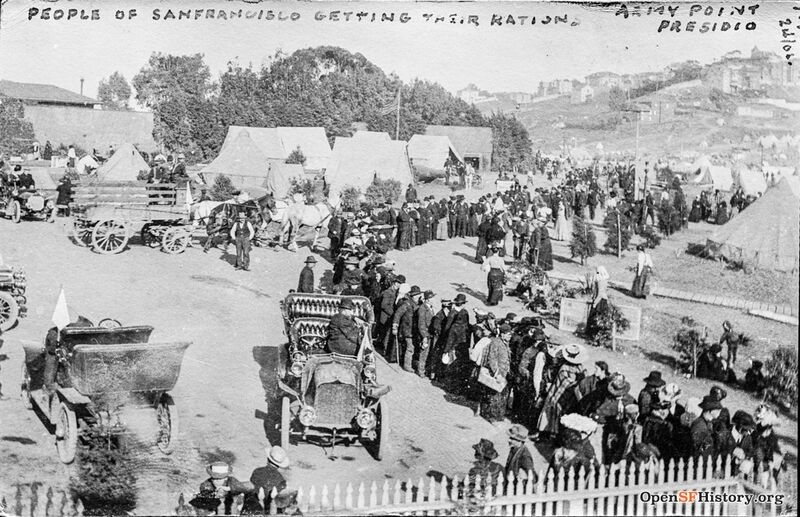

Presidio 1906 people getting rations, many Chinese in line.

Photo: Opensfhistory wnp37.01469

One member of the relocation subcommittee (who before the year was over would be convicted of bribery and extortion, along with the City's mayor, in connection with reconstruction) announced that this last move had been approved by the subcommittee, but he protested further interference with their work since it might cause trouble and confusion for the subcommittee and the City.

The burned out Chinatown, meanwhile, was being overrun by hundreds of relic hunters, looting stores and homes. Half the looters were said to be National Guardsmen there to protect the district. Their commanding officer claimed "they didn't know what they were doing." Besides, he said, it was no worse than what civilians were doing. Accusing the Italians, the Chinese consul general appealed to the governor for protection of property in Chinatown. He returned armed with a letter to San Francisco Mayor Eugene Schmitz authorizing Chinese representatives to reenter the district to protect it. During this period, a Chinese refugee was stoned to death, reportedly by three youths, when he returned to recover his valuables.

Meanwhile, Oakland decided it was sharing San Francisco's "Celestial" problems. Chamber of Commerce directors met to take steps to limit Oakland's incipient Chinatown, which they felt was threatening both business and high class residential districts, whose denizens complained that the Chinese were pouring in in large numbers. The Chamber directors appointed a committee to take immediate action to regulate the influx.

The next day, the Chronicle's headline—NEW FEAR THAT THE CHINESE MAY ABANDON CITY; CITIZENS ARE NOW CONFRONTED WITH PROBLEMS IN WHICH TRADE WITH ORIENT IS INVOLVED—indicated it was purse strings that kept the City together. Apparently, the secretary of the Chinese Legation, here from Washington, wanted to scatter the 500 or so Chinese now at the Fort Point camp site throughout the State, not wanting them to become public charges or accept the bounty of the military or the people.

The Chairman of the relocation subcommittee admitted blunders in establishing the temporary camps. A committeeman declared that if the situation was not wisely handled, the bulk of San Francisco's trade with the Orient might be diverted to other Pacific Coast ports. Seattle was already making a strong bid for this trade and would have liked to welcome San Francisco's Chinese, as would Los Angeles. Another member of the subcommittee took the position that the City was innocent of bias. "What has been done to ruffle the temper of the Chinese?" he wondered. A fourth said the subcommittee had no desire to harass the Chinese or exclude them from full participation in the commercial life of the City.

That same day, the Chronicle published an editorial that perhaps more accurately reflected the City's sentiments: "Some concern is expressed regarding the mooted possibility of the Chinese formerly in business here transferring themselves to other quarters. Such apprehensions are groundless. The Oriental, like the Western merchant, is in trade for profit, not for sentimental reasons. Like the Western, he will see that there are opportunities here and he will seize them. He is not enamored of any particular quarter of the city, and will probably be as glad to get away from his former noisome surroundings as we shall be to have him removed to some convenient place where he can conduct his affairs in a manner that will reflect credit rather than discredit on his race."

Fifteen days had passed since the Earthquake. It apparently had not yet occurred to anyone to ask the Chinese where they wanted to live. Nor did people appear to remember that the Chinese themselves—about 40 merchants—owned one-third of the Chinatown property. The rest was owned by the same sort of slumlords who have always found renting to the poor quite profitable. Chinese remaining in San Francisco had dropped to around 5000, less than a fifth of those here before the quake, and perhaps they thought so few could never make themselves heard. But concern did slowly arise among Chinese throughout the state and Chinese officials in Washington, D.C.

Presidio 1906 refugee camp east of Letterman Hospital.

Photo: Opensfhistory wnp27.2466

Representatives of the relocation subcommittee, the consulate, the Chinese Legation and the powerful Chinese Six Companies met to discuss the problem. The meeting was closed to the public, including the press. The only report came from a member of the relocation subcommittee, who reported that the Chinese had made it clear that they had no authority to enter into an agreement, and that they were very happy with the treatment of their people. Subcommittee representatives told of proposals to cut new thoroughfares through the old Chinatown site and that winding streets might be created along the steep Nob Hill sides. Other improvements called for taking property for public use. For these reasons, if no other, the subcommittee said it would be well to consider a new location for Chinatown.

A subcommittee member said that the Chinese had "conveyed the impression" that if an acceptable location was offered, they would consent to build a new Chinatown elsewhere. Individuals wanted to build wherever they pleased. But, the subcommittee members replied, since the Chinese preferred living together in a settlement of their own, the selection of a specific site for the new Chinese quarter would be in the public interest. So the group agreed to tour the City to look for possible sites and meet again.

A week later, 25 white property owners interested in land in Chinatown met and organized the Dupont Street Improvement Club (Dupont Street was then the name of the longer, narrower portion of today's Grant Avenue which bisects Chinatown) to rebuild Chinatown on the old site "on a thoroughly sanitary plan." A subcommittee was elected to meet with the relocation subcommittee. Several Chinese representatives also attended and presented a petition asking to be allowed to return to Chinatown.

Now, asked or not, the Chinese were beginning to tell the City where they were going to settle, especially when it came to land they already owned. The secretary of the Chinese Six Companies said his organization did not intend to abandon its former site: "(We) own the lot at 736 Commercial Street, for which we paid $23,000 some time ago. We ... will proceed at once with the erection of a nice building on our property. The contract is already drawn and the work of construction will begin the first of the week."

Now, apparently, the Chinese were getting through. Another subcommittee of the Committee of Forty for Reconstruction (which replaced the Committee of Fifty for Relief) met to consider improvements of streets. The chairman suggested that Chinatown's streets be widened and its blind alleys closed up, so that if the Chinese did return there, as he believed they had a right to do, conditions would be as good as possible under municipal regulations.

Meanwhile, the Chinese relocation subcommittee reported to the Committee of Forty about how diligently it had been working in the face of considerable antagonism, that the task of establishing a new site for Chinatown was terribly complex and that it was impossible to relocate the Chinese anywhere they didn't want to live. And, of course, he said, arbitrary restrictions and illegal discrimination were farthest from the subcommittee's designs. Besides, the Chinese had met the previous day and decided they would not move from their former, burned district.

The subcommittee was not about to give up so easily. It recommended locating Chinatown east of Telegraph Hill between Sansome and Front Streets, north of Pacific Street to the Bay. Action was postponed for four days pending the arrival of the Chinese minister from Washington.

A Chronicle editorial agreed that the Chinese could not be kept from returning to their old sites, but recommended that the Supervisors "enact new building ordinances with special reference to ... tenement and apartment house conditions and conduct negotiations with the Chinese on the basis of the ordinance." The editorial also chastised "property owners determined not to forego the great profits which they have been accustomed to receive from the rentals made possible by overcrowding of human beings in unsanitary dens."

Apparently, the Chinese decided that, with the subcommittee's new site proposal, they had not yet spoken loudly enough. Chinese leaders in San Francisco and Washington traveled to Oakland to meet with that city's mayor and the governor to decide whether a Chinatown might be part of Oakland's future. Said an instigator of the meeting: "The Chinese are seriously considering the advisability of establishing themselves in Oakland in the event of San Francisco persisting in their (sic) efforts to give Chinatown a new location. Portland and Seattle are making overtures to us, but the advantage of Oakland will be thoroughly looked into before any decision in the matter is arrived at." The Oakland site discussed was east of Broadway and south of 10th Street where about a dozen pieces of property were already owned by Chinese.

Meanwhile, Dupont Street Improvement Club representatives met with Mayor Schmitz and a relocation subcommittee member because it finally appeared necessary to point out that tourist trade in Chinatown the previous year had amounted to $30 million, that the Chinese paid their share of municipal taxes and that property owners could rent to anyone they wished.

But the harshest attack on the Chinese—yet possibly the one that cleared the way for their return to the old Chinatown site—was still to come. In the midst of a downpour on a Sunday afternoon, a reported majority of the taxpayers and property owners of Telegraph Hill and vicinity gathered at Union and Montgomery Streets, overlooking the site most recently and desperately proposed for permanent relocation of the Chinese. Purpose of the meeting, as explained by its organizer, the pastor of St. Francis Church, was to protest locating Chinatown in their immediate neighborhood. The good reverend said he possessed no prejudice and firmly believed that his listeners wanted to see the Chinese treated in a humane and Christian manner. He then related some of the history of the Chinese and certain dangers and evils that would follow if they were allowed to live near where white children were growing up. To applause, the priest offered a resolution protesting "settling of the Chinese on or about Telegraph Hill" as it "would be extremely injurious to the material and moral welfare of the district." The resolution was unanimously adopted and the gathering organized into the Telegraph Hill Protective Association.

A sudden hush fell over the entire controversy; the pseudo-righteousness of the attack was beyond answer from either the Chinese or the site's advocates. In 1906, take "the church" and add a few property owners, and if you couldn't pick a fight with City Hall you could at least make it withdraw. By doing so, the Telegraph Hill Protective Association probably did the Chinese a big favor. For this was City Hall's predicament: Hunters Point was unacceptable to the Chinese, Chinatown was unacceptable to Telegraph Hill; to suggest anything more remote than that might drive the Chinese and trade with the Orient out of the City and state. So the whole issue died.

For more than five weeks the Chronicle said little about the question. During this period, it reported that the "mayor" of Chicago's Chinatown said many of San Francisco's Chinese had gone there and to New York and Boston, but that most would be returning here, believing that "the City will be a better place for business than ever." The Chronicle grabbed this opportunity to comment that "their expression of opinion ... will help convince some people ... that San Francisco does not treat its Oriental businessmen improperly, otherwise they would have no desire to come back here." Later the newspaper reported that the average number of Chinese immigrating here had dropped from 125 per boat a year earlier to 12 per boat.

Almost three months after the Earthquake and six weeks after the Telegraph Hill rally, the Chinese relocation sub-committee admitted that there really wasn't anything more it could do except allow the Chinese to return to the property they owned or formerly rented. Said the chairman, "If they prove obnoxious to whites they can gradually be driven to a certain section by strict enforcement of anti-gambling and other City laws." The subcommittee was discharged. Not that it really mattered; the Chinese were already rebuilding—with architecture more authentically Chinese than that of the former Yankee structures.

In the end, the Chinese came out of the affair by far the wiser strategists. They had simply said that Hunters Point or any other remote area was unacceptable and then posed the economic threat that they might leave the City altogether if such ideas persisted. Soon after it became known that the Chinese might be made welcome in Oakland, relocation plans were dropped. San Francisco never could stand the idea of giving anything of value to Oakland.