Alexander Books Closes

I was there. . .

by Teresa Moore, originally published in the San Francisco Examiner, April 26, 2023

The last day at Alexander Books at 50 2nd Street, just south of Market Street, April 28, 2023.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

San Franciscans know microclimates. Live here long enough and you learn to pack a sweater, scarf and a jacket because the sun on your back as you leave Potrero Hill in the morning can turn to chilled fog soup by the time you are heading home. San Francisco is also a city of microeras: slivers of time, community and place rich with meaning for those who live through them.

I got to thinking in terms of microeras when I heard artist Sadie Barnette talking at SFMOMA about the long impact left by her father, Rodney, who ran the New Eagle Creek Saloon, San Francisco’s first Black-owned gay bar in the 1990s. “I believe it’s some people’s job to take care of the future, and for whatever reason, I feel like it’s my job to take care of the past,” she said.

Places where people of color can feel seen and heard and at home are precious, even in a city celebrated for its diversity. Here’s a farewell to another one.

Over the past few decades, nearly all the markers of my downtown—Marquard’s newsstand, the M&M, Loehmann’s, the 26 Valencia bus, Hawthorne Lane, Specialty’s, Embarcadero Cinema, Fog City News—have vanished. But no finale has hit me as hard or tracked as closely with my San Francisco as the end of Alexander Books.

Alexander’s fate is tied to the exodus of downtown workers, the market the store was designed to serve. For most of its 32 years, it was a reader’s oasis on the edge of the Financial District. But what’s an oasis without thirsty wanderers? The store will close for good Friday, April 28.

Alexander Books opened November 15, 1990, and closed April 28, 2023.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Alexander Book Company opened on November 15, 1990. I only know the exact date because Bonnie Stuppin, who co-owns the store with her brother Michael, told me so last Friday as I melted down in front of her in the children’s section. Bonnie is what I would call one of my “Sesame Street friends” — the people you see and talk to for years as you go about your day, the merchants and clerks and waiters and bus drivers and UPS drivers who make a place a neighborhood and a neighborhood a home.

Even though last Friday there were “45% off” closing signs all over the place, Alexander was still full enough to be what I have always thought of as the most beautiful bookstore in my world, the book covers bright as flags against the yellow wood shelving and the exposed brick wall on street level where the ceiling soars nearly as high as the kids’ and cooks’ books nook on the third floor.

Everywhere you look, there is something worth seeing, but it always seems airy, never cluttered. The effect is a maximalist mind spa.

Bonnie and I stood there reconstructing the intersections of our downtown timelines. About seven months after Alexander opened, I started as a cub reporter at the oldest surviving San Francisco daily newspaper, back when it shared a building and a publishing arrangement with this august news outlet.

Bonnie Stuppin at register upstairs at Alexander Books.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

One warm afternoon in 1991, I drifted into the store under the spell of Jerry Thompson, the bookseller behind the main counter. I don’t remember what we talked about, but I left with an armload of books feeling as if I’d met a character on the order of Willy Wonka, only Black and gay and handsome and ready to laugh.

In 1992 I interviewed Jerry for the first story I ever published about race, a reported article about how sometimes Black people who grew up post-Jim Crow endured more subtle and complicated experiences of racism than our parents did. A year or so later, I wrote a story about the Sister Circle, the haven for Black women readers he created in the bookstore’s basement. Alexander Book Company was decades ahead of the curve when it came to diversity, equity and inclusion.

In this race and equity column, I’ve written about majority-white spaces that have succeeded in or are atte mpting to be more attractive to people of color. Thirty-two years ago, the Stuppin siblings achieved that when they hired Jerry, an artist whose medium is bringing people together, and let him do his thing.

Even though Alexander is a mainstream, general-interest independent bookstore, for many Black people who shopped there, it could feel like a Black bookstore, too.

In response to the scores of Black women who worked downtown and came in looking for the latest hot Black books, Jerry created the Sister Circle reading series. The events, featuring Black writers, were open to anyone, but they became part refuge, part clubhouse for Black women — myself included — working in spaces where there were few of us and it was hard to be ourselves. In each other’s company at a Sister Circle event, we could indeed exhale.

Nikki Giovanni, J. California Cooper, Anna Deavere Smith, Tananarive Due, Bill T. Jones, Michael Eric Dyson, E. Lynn Harris, Colson Whitehead — these are just a few of the Black literary luminaries who lit up the Sister Circle. The last story I wrote for my old newspaper was a profile of Queen Latifah that included her Sister Circle reading. I won’t forget the day Jerry let me in the green room with Ntozake Shange, the playwright and poet, who refused to face the packed basement audience until someone brought her a whiskey and a burrito.

Jerry made it happen.

Jerry and I became the kind of friends who hang out outside of work. I’ve seen him hold it together behind the counter in the final days, professional, efficient, and handsome as ever — but his laugh is muted and his light dimmed. This ending is a lot for him and his colleagues.

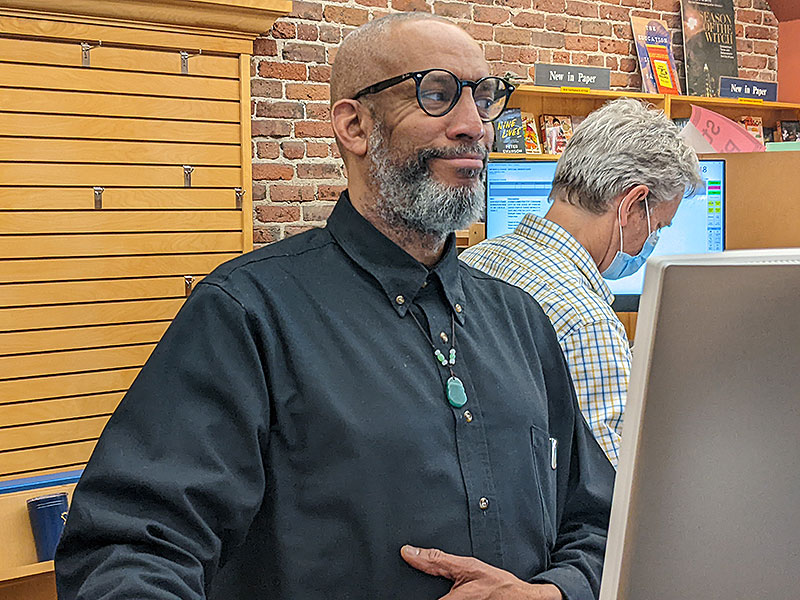

Jerry Thompson on the last day at Alexander Books.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

But having been fortunate to see his genius in effect in lots of other spaces, I know what he’s bringing with him as he leaves this stage. When the secret history of San Francisco is told, Jerry Thompson will have his own chapter. He is the Kevin Bacon of Black, gay, literary, artistic San Francisco—and then some.

Example: Glide pastor Marvin K. White and I met way back when he was the youngest member of the performance group Pomo Afro Homos at a dinner party Jerry threw for his godmother, the poet Lucille Clifton. There, I also met my chosen brother, the artist Michael Ross, who used to manage Patrick and Co. and now runs The Studios of Key West. Yesterday Michael texted about “the Era (sic) of Jerry’s magic and the blessings to all of us around him.”

Thirty-two years. More than half of my life. Maybe not so much of a microera as, indeed, an Era.

Upstairs in the kids’ section, I calmed down long enough to tell Bonnie, “Thank you for so many good stories and memories in the pages and in this place.”

This will be my last column for the Examiner. I’m not ending it because my favorite bookstore is closing, but because this is the right time. A true microera: 18 months and 27 columns. Multiples of nine, my favorite number.

Joy is too small a word for what having this space has meant to me. It has been a privilege to connect with regular readers—I see you, Cornelius and Kitty and Ralph and Sunny—to go places and ask questions and recognize that some things will never make sense. There is so much beauty and energy left in San Francisco. I am grateful for the attention and time you have shared with me. Please keep giving that gift of attention to each other.