San Francisco Singularity?

Historical Essay

by Erica Dawn Lyle

Google bus rolling home on 24th Street in Noe Valley, March 1, 2017. The interior lights offer a soothing light suitable for working via wifi while commuting to and fro from Silicon Valley.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

These days, Silicon Valley’s vision of reality seems to be the most competitive. Indeed, the tech industry seems to enjoy a monopoly on the production and dissemination of mainstream ideas of the future, ideas reaching well beyond Northern California. Almost everyday we hear news about the world of tomorrow being born in the Bay. Google promotes a future of driverless cars and computer glasses, while also claiming to be at work on a giant brain that will harness the thinking power of all humans in one computer. Many of the founders of the most dominant tech firms even profess belief in the imminent arrival of a time, perhaps only a few decades away, when mankind will fuse with computers and at last seize control of the evolution of its own species.

These visions of the future are so full of tech industry dominance and product placement that they might as well be trademark protected as The Future™. And the message is clear: The Future ™ is inevitable. Workers in secret labs at the Google complex are already working on it, and, we are to understand, they are way ahead of us on this one.

Silicon Valley has a name for its millenarian fantasy future: The Singularity. Ray Kurzweil, Google’s Director of Engineering, has written several influential books in which he posits that technological innovation is expanding at such an exponential rate that within a few short decades this progress will surpass the human race’s capability to understand and control it. At that time, artificial intelligence will develop as machines at last become intelligent enough to design new machines with even greater artificial intelligence. As The Singularity arrives, the past and future will fuse into one eternal present in a coming era of "technological change so rapid and profound it represents a rupture in the fabric of human history." Kurzweil and other powerful proselytizers of The Singularity—notably including Google founder, Larry Page, and Paypal founder, Peter Thiel—claim man and computers will then merge and become a new kind of super intelligent being. Transcending all limits of our biology, we will ultimately achieve immortality by uploading our consciousness into computers.

Computer work has taken over most public cafes in San Francisco; this is Starbucks in Noe Valley.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

If this all sounds like another Philip K. Dick story, it’s only because Kurzweil and the other Singularity promoters have stolen one of Dick’s most effective narrative techniques—using what appears to be a storyline about a fantastic future as a coded way to explain the present. Indeed, the breathtakingly surreal and improbable-seeming story of the Singularity is really a kind of fable that obscures the fact that the foretold rupture in the fabric of human history has already occurred. In just a decade or so, as the Internet has assumed a centrality in the organization of almost every aspect of our daily lives, it has become clear that we are living through nothing less than the kind of complete reorganization of our time, space, and consciousness that accompanied the Industrial Revolution. The tech industries in their wealth, power, and influence over so much of the infrastructure of our current world resemble nothing so much as the railroads that ushered in a new era of speed, standardization of time and space and market expansion over a century ago.

While the effects of this speedup and other aspects of virtual life on our consciousness are still being evaluated, the accompanying upheaval in all aspects of our society has been apparent to all. Countless jobs—even entire industries—have vanished; the line between our work and leisure time has disappeared; we now live with the assumption of near total government surveillance. These are just a few of the most commonly mentioned in a now familiar litany of “disruptions” that need not be repeated here.

Another "zombie cafe" along 24th Street in the Mission.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

It is not important for now whether the Singularity is likely or even technically possible – there are still many skeptics in Silicon Valley – but rather that we understand what this fantasy of white male corporate wish fulfillment reveals to us about the way tech industry leaders view our world today. With their public devotion to the Singularity, tech CEO’s are really telling us that they already wish to be seen by us as immortal superintelligent gods, that their technological innovations are already the very instrument shaping mankind’s future evolution. The prospect of future uploading of (select) individual human’s consciousness into cyberspace simply retells as myth the present day ascension to a heretofore unimaginable level of wealth and prominence of a tiny segment of the world’s population that in the present day has sought to hoard for itself the world’s remaining resources and leave us mere mortals behind in our pathetic human precarity.

In other words, as William Gibson famously wrote, “The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed.” Which raises an important question: when Kurzweil says – and I quote – “We will transcend our biological limitations,” does he mean “we” in the sense of every single human being on Earth? Or can we presume that some consciousness won’t be considered by the shapers of our evolution to be valuable enough to preserve for all of eternity.

Philip K. Dick’s novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, is set— where else—in yet another alternative future San Francisco. After a nuclear war, the wealthy and the well-connected have fled the radioactive city for colonies in space. The humans left behind on Earth dwell in a dilapidated and toxic city. This future San Francisco is nostalgic for animals in the way the dot-com city today longs for street life. But real live animals are extremely rare and expensive so the strivers that remain on Dick’s Market Street must jockey for social position with purchases of ever more expensive and more lifelike robot simulations.

Like all San Franciscos, past and future, the city in Do Androids Dream is haunted by a sense of loss—in this case, the loss of a clear sense of what it means to be authentically human in a world humans now share with extremely lifelike machines. I wonder sometimes if the relationship between mankind and earth that Dick describes here is not also something like the relationship between the street and the Internet today, where the street gradually grows ever more anxious that it is being left behind by the beginnings of an exodus of mankind into cyberspace.

As the streets become more and more forlorn and abandoned in the digital age, they nonetheless remain the place where we go to search for authenticity. Perhaps the ubiquity of cell phone cameras today has turned us all into Situationists on the hunt for poetic, out of the way locations in the city. A quick perusal of my friends’ Instagram feeds reveals a beguiling collage of cut up urban places, an alluring city of the mind cobbled together from snapshots taken almost simultaneously in urban places all over the world. Scrolling through them, I begin in a shadowy, snow-filled back alley and jump cut to a rooftop view of a city skyline. Suddenly, I’m in front of an alluring neon bar sign in downtown Los Angeles, and then I’m on a rowboat on a nameless industrial canal. I continue to ramble along on a virtual adventure that takes me to a grid of fire escapes at dusk, inscrutable graffiti on a brick wall, the view from within a crowd at an anti-police brutality march, a mysterious and weathered wooden door, until my journey comes to an end amidst some stage divers in a sweaty basement punk show.

Again, the riddle: does taking the picture make these moments staged? Or does it prove they were real? Maybe Instagram has collapsed the distinction. According to the terms of service agreement accepted by all users, the company owns all images posted on its site and can use them in any way it wants, including selling the images to advertisers, without having to pay any royalties to the original photographer. Or to put it another way, social media has come up with the neat trick of getting its users to star in and film their own advertising campaigns, all for free. I imagine the virtual adventure sequence of the Instagram feed again, but with the last frame filled with the logo of Converse sneakers or Levi’s. Susan Sontag famously wrote of the “acquisitiveness” of photography. But one wonders what Debord would have made of the cell phone camera, a device seductively complicit with our desires to wander and see and share but also with our desire to possess—a desire that turns the Situation into Spectacle in an instant.

Ah, well. So the prospects of a digital dérive have perhaps come to naught—though I’m sure, were he alive, Debord would have found a way to take credit for the idea anyway. The new cellular Situationists have even given up their restless search. I can see them now from out the window where I live above a train station in Brooklyn. They emerge from the underground and, reunited with the city’s free floating wireless signals, they perch at the top of the steps, peering into their devices for guidance. They stand stock still, as if utterly terrified to take even so much as a step, until at last they put in their ear buds, and, having received their instructions, they set out toward their destination.

Waiting in line at a supermarket, everyone is on their "smart" phone.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

The maps on these handheld devices precede the territory. Indeed, early travelers to the area would have found uncharted space on their digital maps, as the street was largely shuttered and vacant when I moved here. Over time, however, as if the phones were a kind of magic wand waved over the street, the kinds of places the maps list as attractions began to appear on the street in real life. When the wine store, the cold pressed juice shop, and the artisanal bakery materialized as if overnight, the neighborhood had not even suffered a long and protracted period of cool dive bars, gritty storefront art spaces and illegal DIY music venues. Instead, it was like the new high end shops had been unpacked out of a box overnight—or to use a digital metaphor, had been simply copied and pasted from another previously settled neighborhood.

These new businesses, however, seem oddly haunted by existential crises, by questions of their own authenticity. Several of these businesses—even the very newest to the street—post signs in their windows that implore passersby to “Shop locally” or “Support local business.” The new cafes, meanwhile, return to us the aura that coffee was said to have lost in the age of mechanical reproduction, by brewing a unique cup of coffee, fresh and one at a time, for each and every customer.

It is almost as if each high end toy store located in the ground floor of a new condo secretly wishes it were instead a junk store, as if the vegan donut shop wishes it had started out back in the day selling crack. These anxieties about authenticity appear in Dick’s novels as well, where his alternative future San Franciscans are driven to melancholy with the never-ending search for authenticity, while ever-haunted by its negative double, nostalgia.

Indeed, in the once-gritty and artistically vibrant areas of the city now gentrified by tech workers, the rarified tastes of today’s tech workers call to mind those of the Japanese elite in The Man In The High Castle, who had cultivated a penchant for collecting Pre-War Americana. In High Castle a white character makes a living selling relics like an authentic American Civil War service revolver or a Mickey Mouse watch to rich Japanese collectors. Yet another white works in a factory that secretly mass produces fake Civil War service revolvers for sale on the black market to meet the growing demand for “authentic” Americana.

At least 20 of these luxury "tech" buses rolled by in less than a half hour of walking along Noe Valley's 24th Street around 5:30 pm on March 1, 2017. They run 24 hours a day and bring tech employees to Google, Facebook, Electronic Arts, LinkedIn, Genentech, Apple, and many other large tech companies in Silicon Valley.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

For a deeper understanding of Silicon Valley’s corporate appropriation of utopian language today, one must go back to the era of 1960s countercultural communalism during which early experimentation with the Internet began. While that era is often remembered today for the Back To The Land movement, in which many young seekers came together to form intentional communities in rural places like Drop City and The Farm, the communalism movement built strong and lasting networks in the city of San Francisco and throughout the Bay Area.

The decentralized and autonomously organized connectivity practiced by Kaliflower, The Food Conspiracy, and other communes corresponded with larger trends in radical thought of the era. Black Panther founder, Huey P. Newton, famously gave a speech at Boston College in 1970 in which he declared that the Panthers no longer believed a socialist nation state was possible. Instead, the group would now be dedicated to “intercommunalism within a cooperative framework.” The group, which had already established their own nationwide network of free breakfast, health care, and legal aid programs as well as a thriving nationally distributed newspaper, now advocated a world revolution to establish a global group of interdependent socialist communities.

This dream of decentralized global connectivity, of course, also corresponds to the popular fantasy of the Internet and its chief idea that if all of the people of the world were able to communicate directly with each other, cultural differences would fall away and the world would know greater peace and understanding. In late 1968, Stanford computer researcher Douglas Englebart gave a historic demonstration—later called “The Mother of All Demos”— of a complete computer hardware and software system that for the very first time in one machine included such elements of modern personal computers as hypertext, windows, the mouse, video conferencing, and word processing. Then seen as a simple machine for the computation of numbers, Englebart’s NASA-funded research team reimagined it as a device to aid communication and retrieve information. The promise of this new technology rhymed with countercultural communal aspiration. Indeed, the citizens of Callenbach’s Ecotopia administered their new free state through consensus affinity group meetings and direct discussions with their government using a kind of proto-internet.

In his book From Counterculture to Cyberculture, Stanford professor Fred Turner traces the utopian rhetoric of Silicon Valley today back to its origins in the 1960s communes, while also showing where the tech industry crucially turned toward the free market and networked individuals. His story follows Stewart Brand, the publisher of the most famous surviving document of the communal era, The Whole Earth Catalog – a book which Steve Jobs once called “Google in paperback form.”

Published in the Bay Area after Brand took a tour of Northern California communes, Brand’s catalog listed where to learn about and purchase supplies for then-obscure practices like organic farming, solar power, recycling, or desktop publishing, while also endorsing then-rare products like high quality outdoor camping equipment and mountain bikes. The catalog published peer reviews of these goods and services written by readers. While the Kaliflower communalists practiced collectivity, participation, and sharing in a kind of gift economy, Brand’s catalog promised “access to tools,” and emphasized individual empowerment and a kind of frontier self-sufficiency. Prefiguring future utopian claims about the Internet, Brand claimed his catalog signaled a new era in which power would no longer be in the hands of big business, the church, and the state. Anticipating the Silicon Valley Singularists of today, Brand wrote, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.”

Brand’s catalog -- modeled as it was after the Sears and L.L. Bean catalogs -- proved immensely popular with mainstream readers and won a National Book Award in 1971. As its championed for a mainstream audience products once associated with the communal underground, the catalog signaled a generational turn away from authentic communal practice toward new alternative lifestyles that idealized personal success and fulfillment while still decorated with the trappings of countercultural life.

Brand would continue throughout the 70s and 80s to be an influential figure in the development of the cyberlibertarianism associated today with the Internet and Silicon Valley (he had, in fact, been the camera operator at Englebart’s demo). In 1985, he cofounded the early internet dial-up bulletin board system, The Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link (or The WELL), and is today credited with the invention of the term “personal computer”.

Brand’s vision of the individual armed with the right tools to decentralize power fused with the rise of the personal computer in Apple’s famous television commercial for its new Macintosh PC that debuted during the 1984 Super Bowl. The ad opens upon a dystopian Orwellian setting in which ranks of identically-dressed workers march through a long tunnel past rows of screens on which a Big Brother-like figure is giving a propaganda speech. A woman dressed like a track and field runner appears, being chased by riot police. She is carrying a hammer and as she nears a particularly large screen she lets fly the hammer, which smashes the screen – and Big Brother’s face. In the smoky aftermath, a caption appears on screen that reads, “On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like Nineteen Eighty-Four.”

Tech companies have portrayed themselves to be in a winning battle with the riot police of the world ever since. Indeed, Twitter and Facebook memorably rushed to take credit for the rapid spread of the uprisings of 2011’s Arab Spring. The dream of social change through decentralized connectivity remains a huge part of Silicon Valley’s rhetoric, yet in reality we see instead more corporate appropriation of radical practice. The very form of Twitter was inspired by Txtmob, a service developed by The Institute For Applied Autonomy that allows self-selecting members of unmediated groups to communicate directly with each other – whether friend or stranger -- en masse by cell phone text message. In 2004, protesters battling riot police at the Republican National Convention in New York City armed themselves with Txtmob to coordinate impromptu demonstrations, evade riot police, and to share rapidly in protected anonymity changing information about the direction of protest march routes and conditions. This network of users sharing SMS messages was one of the models for what would two years later become Twitter. Now a publicly traded company, Twitter has sought to find ways to monetize the user information of the site’s two hundred and eighty-eight million users by selling their information to advertisers. Recently the company announced its acquisition of the data aggregation specialist, Grip, in hopes that the analytics firm will help mine users’ tweets for information that can be sold to advertisers, academics, and even the police.

Still, the appropriative smash-the-state rhetoric of the long-ago Apple ad has persisted in Silicon Valley, but today, as it was with Thatcher and Reagan, it often comes from the very people running the state. In his recent book Citizenville, former San Francisco mayor Gavin Newsom proposes a future in which the bureaucracy of participatory democracy has been dismantled and replaced with the crowd-sourced administration of the city by small, decentralized groups of like-minded citizens who self-organize via cell phone app. “Citizen engagement in the twenty-first century won’t be about congressional and presidential elections,” he writes. “It will be about personal involvement at the most local levels. It will be about individuals organizing themselves.”

Readers can be forgiven for thinking Newsom has lost his mind and joined up with the anarchist protesters who once staged guerilla theater demonstrations in front of his campaign headquarters. But when we look closer, we see Newsom’s ideas for reorganizing society more closely resemble the ideas of citizen voluntarism put forward in conservative UK Prime Minister David Cameron’s idea of The Big Society. Newsom proposes that citizens can be encouraged to care for the city by getting rid of the bureaucracy of city administration and instead making government more like a computer game – “like Angry Birds, but for democracy.” Citizens will be rewarded with virtual citizenship points – redeemable for real cash prizes -- for banding together to fix potholes and repair broken stoplights. Newsom rose to prominence in San Francisco while still a member of the Board of Supervisors, by championing legislation to slash welfare checks for the city’s homeless. In Newsom’s proposed future – as in grim post-Thatcher England – we see this logic now extended to the entire populace, as citizens will be obliged to provide and fund for themselves the vital services that were once expected of a government that is now too bankrupt and broken down to carry them out.

Though widely panned, Newsom’s book is sadly representative of current thinking about government in municipalities across the United States and Europe, where in an era of austerity services have increasingly been cut and public goods privatized. But perhaps the most pernicious feature of Newsom’s book is its proposal for monetizing the altruism once associated with citizenship. With the idea of cash rewards for helping out, Newsom extends into new areas the neoliberal project of monetizing all aspects of our life that has found its most widespread expression of late in the rise of the so-called Sharing Economy.

In a formulation that does not bode well for Newsom’s proposed self-organized cellular citizenship, private citizens have now demonstrated with The Sharing Economy that they are most willing to self-organize via cell phone not to administer city government services, but rather to arrange new ways of buying and selling goods and services. Services like Airbnb and Uber have allowed participants to generate money by renting out spare rooms in their homes or by giving rides to strangers who they meet via cell phone app. The use of the word “sharing” here once again evokes the communal life of the 60s, when it was common to allow a communard to crash on the couch or to pull over and offer a ride to a hitchhiker. But these small gestures, once offered for free, are now only for sale, their rates set by online agreement. Beyond Airbnb and rideshare apps, other services offer the rental of power tools or parking spaces and the performing of small tasks. There is seemingly no area of life that does not now have a biddable price that can be set by users on the Internet.

Indeed, the only thing that is actually shared according to the traditional definition of the word in the Sharing Economy is the labor of participants. Accordingly, Silicon Valley has cast the Sharing Economy as a kind of “right to work” issue; the new apps are simply just one part of the tech industry’s heroic disruption of needless government intervention into the free market. Tech boosters claim that these services now empower private citizens at last to make an end run on the regulation and bureaucracy that keeps them from, say, operating hotels or taxi cabs without a license. In reality, the services function like a cyber version of day labor companies or office temp services, where uncontracted workers are matched quickly with buyers who need labor for specific, one-time purposes. And all this produces massive profits for the “neutral” platforms that claim they are only marketplaces connecting clients to customers.

In any event, this “marketplace” is hardly as free and open as Silicon Valley would like us to think. As in a day labor site, workers for Uber, for instance, are obliged to accept the company’s lowball fixing of pay rates and charges to the customer, in exchange for the ease with which the Uber platform can find them work. In the process, these workers enter into direct competition with established professionals in fields like the hotel and taxi industries, where Sharing Economy workers underbid pay rates, thus pushing overall wages to the bottom and putting established workers out of jobs. Sharing Economy sites represent a further atomization of the workforce into low pay, low skilled positions, and non-unionized positions where workers labor without health care benefits or protection against injury – the very protections industry regulation are meant to provide. A Wall Street Journal commentator recently called the Sharing Economy “The New Feudalism”.

Perhaps the Sharing Economy then is the apotheosis of the Internet, when new technology has at last fused completely with neoliberal values to most efficiently reorganize not just our economy but our expectations about the very nature of employment in our society. This “disruption” follows a similar reimagining of our expectations about one of most basic human needs, shelter, and our very understanding of who or what a city is for. A 2014 city-sponsored report that found that between 25 and 40% of rooms that could be rented to residents of the city were in fact being rented instead at hotel room prices to tourists on Airbnb.

But, of course, the rupture in human history foretold by the acolytes of The Singularity in Silicon Valley has already occurred -- in some ways more quietly than others. Within the workings of the Sharing Economy we see crystallized the new ethos of our age. As I have argued throughout this essay, we can no longer understand gentrification to be only about the manipulation of urban space – to be simply about real estate machinations, or the racist removal of people of color from the urban core. While gentrification is, of course, about those things, increasingly it is also about nothing less than the complete reorganization of our inner lives — up to and including the manufacturing of our deepest desires and the redefinition of all human interactions. As we learn to expect that no stray increment of time or space is too small, no human emotion too fleeting to be monetized, we see even our utopian longings for human connection stolen and sold back to us. In a world where few can imagine an alternative to Capitalism, we see opening up before us the door to The Future – which increasingly looks like an eternal present from which there is no escape. It is a grim vision, to be sure. But, make no mistake, there is nothing futuristic about it.

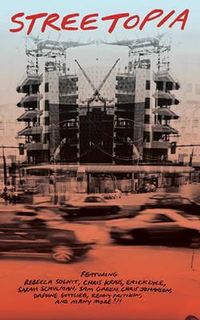

Excerpted from Streetopia, in the essay "The Uses of Market Street"

See other parts of this essay: