Christopher Buckley and the Politics of Urban Growth

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

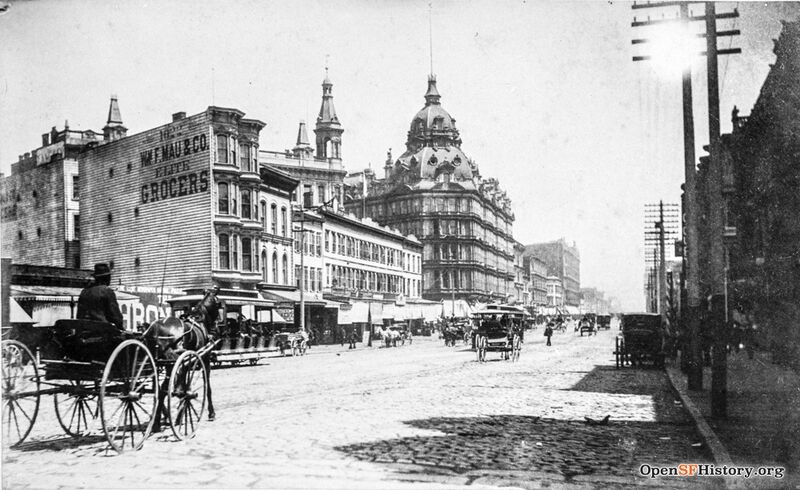

View northeasterly over Chris Buckley's city with the Hall of Records looming in foreground, 1888.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp71.1572

Christopher Buckley was born on Christmas Day in 1845 in New York City, the son of Irish immigrants, his father a stonemason. At the age of sixteen, young Buckley and his family moved to San Francisco. He worked briefly as a streetcar conductor but soon found a more congenial place as a bartender working for Tom Maguire. One of the premier saloonkeepers and political figures of the day, Maguire had worked closely with David Broderick in the 1850s. In one particularly controversial transaction (perhaps a forerunner of Ralston’s water plan), Maguire sold a theater to the city for use as a city hall. Maguire's bar provided a political education for its eighteen-year-old bartender, an education augmented by William Higgins, a powerful Republican who took Buckley under his tutelage for a brief period in the late 1860s. By the time he was twenty-one, young Buckley struck out on his own as a saloonkeeper, later established a brief partnership with Maguire, then moved to Vallejo for two years.(27)

Buckley returned to San Francisco in 1873, a convert to the Democratic party. He began to work with a number of leading Democratic organizers, emerging slowly as a significant figure in his own right. Though blind by the late 1870s, Buckley did not miss a stride in his march toward power. In 1880 he convinced Kearney to swing the WPC organization behind Winfield Scott Hancock, the Democratic candidate for president, then claimed the credit for carrying California for the Democrats for the first time since the Civil War. The same year, Buckley and other members of the Yosemite Club took over the local Democratic party. Within two years, most city politicians agreed that Buckley held sway as boss of the San Francisco Democratic party and that the Democrats could usually mobilize a majority on election day. Buckley dominated local politics for almost a decade before meeting defeat in the early 1890s.(28)

Buckley and the Democratic Party

When Buckley converted to the Democrats in 1873, he joined a party that had spent most of the previous twenty years in the political wilderness. From the Vigilance Committee of 1856 onward, only one Democrat had sat in the mayor’s chair, and Democratic supervisors usually found themselves in the minority. In 1875, in part because of Ralston’s water scheme and in part because of a third party’s brief entrance into city politics, Democrats won all city offices and most legislative seats. Led by Mayor Bryant, they repeated the sweep in 1877. These victories inaugurated a quarter-century during which Democrats usually won the mayoralty and majorities on the Board of Supervisors. The victories sometimes came only by narrow margins, and they were punctuated by a number of defeats: in 1879 (by the WPC), in 1881 and 1890 (by Republicans), in 1892 (by an independent candidate), and in 1894 (by Adolph Sutro, running as a Populist).(29)

Buckley’s title, “boss”—bestowed, to be certain, by his opponents—came not from any public office he held nor from any formal position in the Democratic party structure. His power derived instead from his stance in the center of a complex set of personal relationships that reached out to many parts of the city and to many of the city’s Democratic voters. During the early 1880s, Buckley customarily operated from his Alhambra Saloon on Bush Street; after he sold the Alhambra in 1885, he met with supporters in various saloons and later in the Manhattan Club, a Democratic organization for which Buckley bought a Nob Hill mansion. His organization always had a feudal quality about it—Buckley might be king, but he reigned because of the loyalty of several great nobles who had power bases of their own. At times, some of these other Democratic leaders rose in revolt and tried to seize the reins of power from Buckley, but throughout the 1880s he quashed such rebellions.(30)

Buckley chose Democratic candidates carefully. William Bullough, Buckley’s biographer, has provided the following description of Buckley’s tickets:

Slates presented by the Buckley organization were not composed of party hacks and incompetents but rather of members of the middle echelons of the business community, individuals of sufficient talent and respectability to appeal to voters throughout the city. Tickets were also persistently cosmopolitan, including nominees whose surnames identified them with politically potent Irish, German, French, Jewish, and Italian communities.

Washington Bartlett, Buckley’s choice for mayor in 1882, had arrived in the city in 1849, became a journalist and publisher, then switched to the law, business, and real estate. A veteran of the Vigilance Committee of 1856. Bartlett had served three terms as county clerk, elected on the People’s Party ticket, and two terms in the state senate. As mayor, Bartlett distinguished himself primarily by holding down tax rates and city spending. His successor. Edward Pond, was cut from similar cloth. Despite some disagreements. Buckley gave both men Democratic nominations for governor. Bartlett won in 1886. but Pond lost in 1890.(31)

The Politics of Urban Growt.

Bartlett and Pond presided over a citv undergoing rapid growth during the prosperous 1880s. New one- and two-family houses, exuberant local variants of prevailing styles, marched up the hills and through the valleys of the Mission District and spilled westward across the Western Addition. The new housing stimulated extension of streetcar lines, street lighting, water, and other utilities. Some of the most controversial. and potentially lucrative, political decisions of the 1880s dealt with franchises to private utility companies. Demands for streetcar franchises produced twenty-six grants in 1879 alone. When Buckley’s slate proved victorious in 1882, he found himself popular not just with would-be traction magnates but with many other businessmen as well. In Buckley’s words: “It was surprising to see how universal was the desire among men of substance, firms and corporations, to get on the right side of politics.” Between 1879 and 1884, the Market Street Railway Company (owned by members of the Southern Pacific's Big Four) acquired the basis for a near-monopoly on streetcar transportation.(32)

Granting of franchises continued during 1885–1886 when Bartlett served his second term teamed with a Republican Board of Supervisors. With Republicans occupying eleven of the twelve supervisorial seats, franchise seekers turned their charms upon Buckley’s Republican counterparts. Martin Kelly later recalled that one particularly lucrative veto override brought him and each of the Republican supervisors $5,000 apiece. The Spring Valley Water Company already had a monopoly but struggled—successfully—throughout the 1880s to prevent lower water rates. Annual battles also erupted over contracts for street lighting, with electric companies increasingly challenging the near-monopoly of the San Francisco Gas Light Company.(33)

Market near Turk Street, c. 1889.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.03782

Like his New York counterpart, Buckley saw his opportunities—he called them “certainties”—and he took them, emerging from his years of power independently wealthy, with a portfolio full of bonds (including Spring Valley Water Company, gas and electric companies, and streetcar companies), real estate investments throughout the state, and partnerships in a number of firms doing business with the city. By 1890, he was worth an estimated $600,000. Despite this wealth, Buckley’s biographer avers that “Chris Buckley did not corrupt municipal polity in San Francisco.”

It already had been corrupted, if not by individuals certainly by the historical process of urbanization which rendered government under the Consolidation Act of 1856 and its maze of amendments both ineffectual and obsolete. The Blind Boss and his organization . . . brought a rough form of rudimentary order to the chaos existing in municipal affairs and provided an interim—if extralegal—government that perhaps facilitated otherwise impossible civic development.(34)

Bullough might have added two further observations. First, San Francisco had long become accustomed to “extralegal” approaches to government, from the Vigilance Committee of 1851 and then 1856, through the latter’s apotheosis by the People’s Party, to the Pick-Handle Brigade of 1877. Buckley’s organization, of course, differed from these others. They all were organized by and supported by the city’s leading merchants. Lower-middle-class businessmen, especially saloonkeepers, created Buckley’s organization, and its power base stood squarely in the working class. Second, “civic development” in the 1880s most often proceeded along the lines of least resistance—and least cost. Franchises cost the city treasury nothing (they even generated modest revenue), and they benefited many—the company, the consumers, and the city officials who voted right. Buckley and the Democratic mayors of the 1880s reduced both the city’s tax rate and its assessed valuation, resulting in substantial tax savings for property owners. As one result, school construction lagged far behind the growing school-age population. Contracts were awarded in 1871 for construction of a new city hall, but it was incomplete when Buckley came to power in 1882. Niggardly appropriations throughout the Bartlett and Pond administrations kept construction at a snail’s pace. By the early 1890s, the still unfinished building— tagged “the new City Hall ruin”—stood as testimony to the priorities of city government: civic development would come through private enterprise, not through expenditure of public funds.(33)

Buckley’s Fall from Power

Despite success in stabilizing city finances (largely by collecting back taxes from utility companies) and in reducing taxes, Buckley always had to battle with opposition to his regime, both within his party and outside it. The major outside opposition came from the Republicans, led by William Higgins, Martin Kelly, and Phil Crimmins. Their approach to politics differed only slightly from that practiced by Buckley. Buckley’s opposition within his party also included some whose approach to politics differed from Buckley’s only in that he was boss, and they wanted to be. In 1882, Buckley’s opponents included the elder James Phelan, George Hearst, and a few other notables in addition to the remnants of the group the Yosemite Club had defeated for party leadership in 1880. Eventually Hearst reconciled himself to Buckley and went to the U.S. Senate with the boss’s support. Anti-Buckley organizations came and went throughout the 1880s, including the improbably named Anti-Boss Anti-Monopoly Lone Mountain Democratic Club of San Francisco. In 1886, opposition included not only some who had long opposed Buckley but also a few members of his own organization. Charged with responsibility for virtually every fault in the city, Buckley usually shrugged off such accusations; he once said that “in the boss business you have to let it go.” By the late 1880s, scandals in the schools combined with other issues to provide opponents with ample ammunition against the boss. Many Buckley opponents coalesced in 1890 as the Reform Democracy and soon helped to give birth to the Committee of 100, which included the younger James Phelan, William Coleman, former mayor Pond, Gavin McNab, some erstwhile Buckley supporters (one of whom decided the boss had become “too heavy a load to carry"), and personal enemies of Buckley.(36)

In 1891, Buckley came under the scrutiny of a grand jury. William Bullough described the investigation as conducted by a “biased judge" and ten “hostile jurors." After months of widely publicized testimony, the state supreme court ruled that the grand jury had been constituted in violation of both the state constitution and the city charter. Buckley, taking no chances, made an extended trip to Canada, returned briefly to the city, then departed for England. The 1892 primary, conducted during his absence, saw reformers rout the organization, using tactics as manipulative as those of any boss. They printed their ticket, for example, on paper that could be read even when folded and so thin that several ballots might be held together. This “isinglass ticket" and similar maneuvers led Martin Kelly to confess: “When I saw what was within the scope of a reformer’s vision, it was with sadness and humility that I realized the narrow limits of mv own imagination.”(37)

This disarray of the Democrats during the early 1890s found reflection in city politics. In 1890, lavish expenditures by Leland Stanford guaranteed both his own reelection to the U.S. Senate and a Republican sweep of city offices. Reformers accused Buckley and Senator Hearst of cutting a deal with Stanford, allowing a Republican victory in 1890 in return for a Republican washout in 1892 when Hearst would need a Democratic legislature to secure another Senate term. By 1892, however, Hearst was dead and Buckley was out of the country. Anti-Buckley Democrats managed to carry most city offices, but the two leading candidates for mayor came from neither major party. The same situation recurred in 1894 when Adolph Sutro won mayoral office as a Populist. Not until 1896, when James Phelan won the mayoralty as a Democrat, did the two major parties’ candidates recover the top spots in the returns. By then, Buckley remained useful to the reformers is a straw man but could not recover his lost power. The new “boss” of San Francisco’s Democratic party was Gavin McNab. Born in Scotland, McNab worked as a hotel manager before being admitted to the bar in 1901. His organization, the Junta Democrats, were largely professionals and businessmen, but they included a few former Buckley associates, a former WPC activist, and a number of federal patronage appointees.(38)

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 6 “Politics in the Expanding City, 1865-1893”