Adolph Sutro

Historical Essay

by Annalee Newitz, January 13, 1999

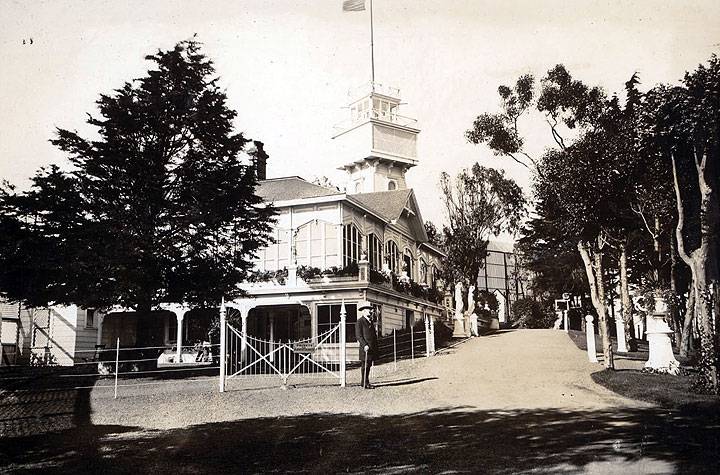

Adolph Sutro in front of his mansion on the Heights, c. 1890

Photo: Private Collection, San Francisco

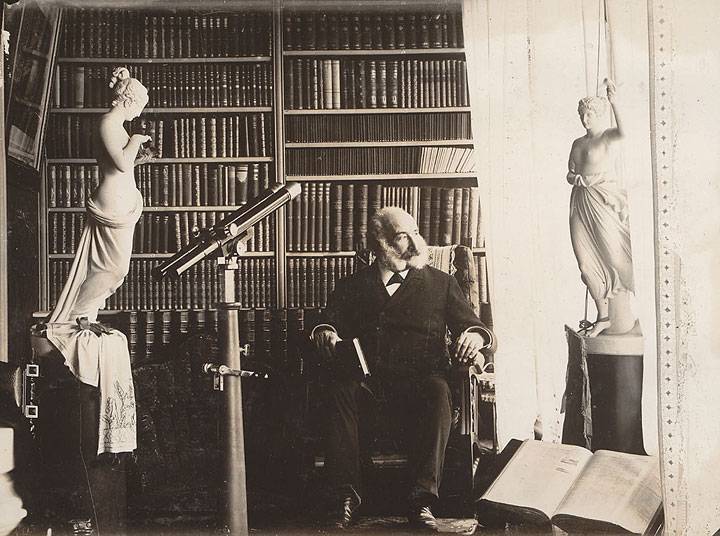

Adolph Sutro in his library.

Photo: Bancroft Library

Fittingly, Adolph Sutro's memory was demolished in the same way that it was made: on the free market. His life story is in fact a kind of individual blueprint for the fortunes of an entire generation coming of age during the post-Gold Rush years of Big Mining and Big Industry. Like many young people in 1850s California, Sutro arrived in San Francisco as an immigrant. Born in Prussia to Jewish parents, he was an engineer by trade who seems to have wanted nothing more than to be a visionary entrepreneur. He ended up becoming a well-known madman whose attempts to build Nevada's Sutro Tunnel in the Comstock Lode (a heavily-mined mountain range near Virginia City) made him one of the late nineteenth century's most infamous anti-monopoly agitators in the worlds of government and finance.

Sutro made millions once the tunnel was finished and he sold his share in the Sutro Tunnel Company, but it was his struggle to complete the project--often referred to in the press as Sutro's Folly -- that convinced him the Octopus must be destroyed. The Sutro Tunnel was supposed to piggyback on the fortunes of Gold Rush magnates who owned all the mines in the Comstock. Because miners had to go so deep underground to reach lucrative lodes of ore, they often suffered or even died due to the incredible heat (up to 140 degrees) and poisonous gasses. In some mines, laborers could only work for fifteen minutes before having to come up, breathe air, and recover. Sutro imagined joining the shafts of the numerous mining companies' tunnels together with one great tunnel which would serve as a ventilation shaft and drainage device -- thus making the workers more productive and in many cases sparing their lives. It would also serve as a transportation tunnel for mined ore, thus biting into the railroad monopoly held by William Sharon in the Virginia City area. Sharon and some of his fellow railway and bank magnates repeatedly attempted to defeat Sutro's bids to start the tunnel, despite the fact that Congress drafted a bill to loan Sutro five million dollars for it (he was later given two million).

After several years of Congressional feuds over Sutro's tunnel and bitter PR battles in the press, a six-week fire in the Comstock mines killed 49 workers and maimed several dozen more. Sutro immediately gave an impassioned speech to a group of miners about the merits of his tunnel. Raising money from the miners themselves, and dipping into the pockets of foreign investors like the Bank of London, Sutro finally managed to beat the Octopus and start digging in 1869. Because he was so popular among the laborers, Sutro was also able to get a special deal: rather than paying his workers the standard four dollars a day, he paid them three and gave them an additional one dollar a day in Sutro Tunnel stock (which they could get only if the tunnel were finished). This arrangement makes Sutro perhaps one of the first entrepreneurs to offer his employees stock options.

As if he were running a present-day multimedia startup, Sutro spent years fighting to make his crazy ideas come to fruition, motivated his employees with stock options, and sold his company as soon as it went public in 1879. We might say that the tale of Sutro Tunnel Company vs. the Southern Pacific Railway resembles the current battle between Netscape and Microsoft. Like the Sutro Tunnel Company, Netscape is the independent alternative to Microsoft's corporate octopus; and like Sutro, the head honchos at Netscape are going to the U.S. government to protest Microsoft's monopolistic business practices. Also like the Sutro Tunnel Company, Netscape is hardly poor or oppressed. It is simply smaller and less politically powerful than Microsoft.

Mirroring the experiences that the heads of many computer corporations have today, Sutro gained power -- and lost it -- during a period of dramatic economic transformation in the United States. His civic monuments fell to pieces not because his City scorned him, nor because later mayors wanted to trash the memory of a great Progressive who gave out over ten thousand free Salvation Army tickets (the equivalent of food stamps) during the economic panic of 1893. Put simply, San Francisco has forgotten Sutro because his money ran out. When he died one hundred years ago in 1898, his property immediately fell into disrepair. Without Sutro at the helm, his real estate empire fell apart; and with the advent of another depression in the 1930s, the very last of his family's inheritance was lost. Tellingly, it was during the 1930s that most of his property and public works were finally destroyed (although his great library, once said to be the largest individual library in the world, was mostly consumed in the 1906 fire). In the end, San Francisco forgot Sutro because no one was willing to pay to preserve his memory. And so his legacy has eroded into a name for various locations in the City landscape, divorced from its political context.

--excerpted from "In Search of Adolph Sutro" in the San Francisco Bay Guardian