Amplifying Working Class Culture in Southeast San Francisco: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

<font size=4>The Cultural Map of Southeast San Francisco</font size> | <font size=4>The Cultural Map of Southeast San Francisco</font size> | ||

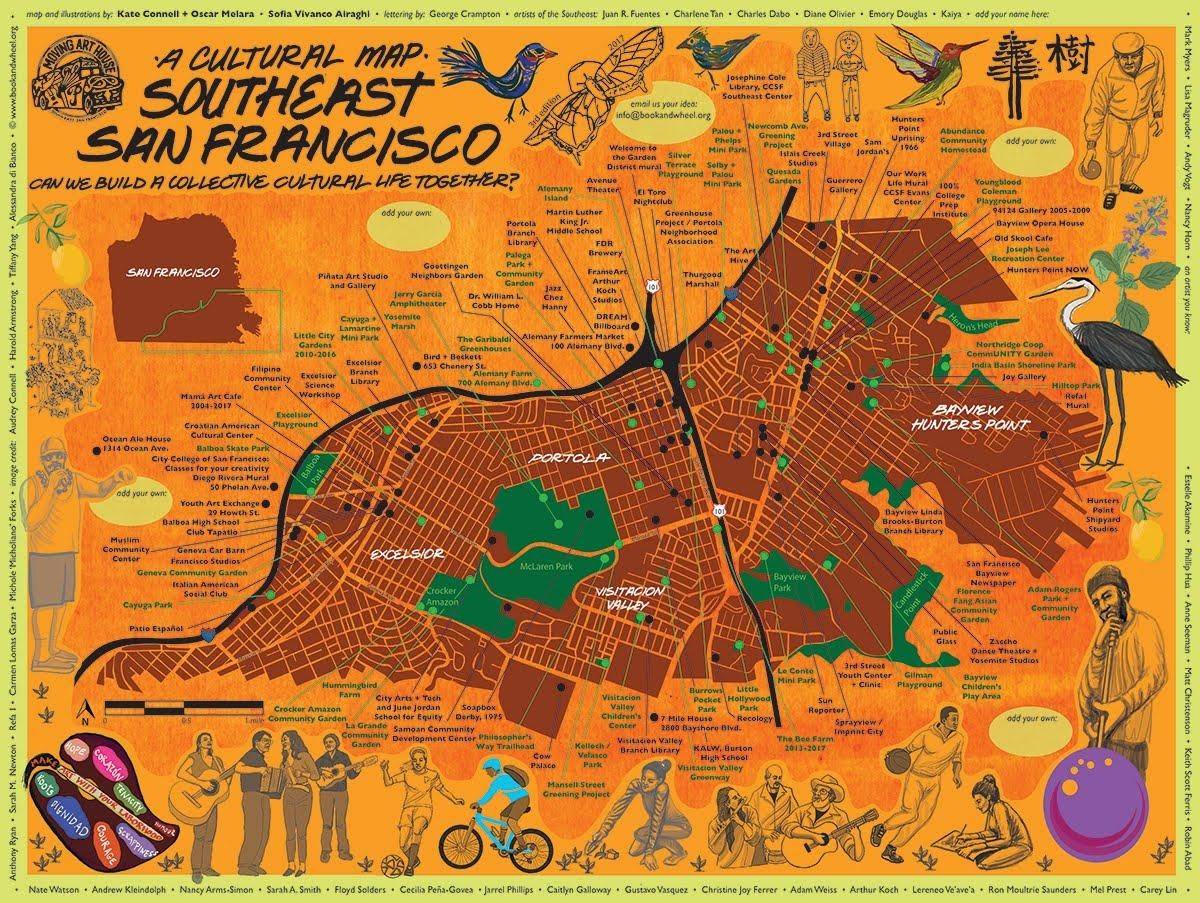

Our current project is a map for residents of our region. We created and update the map in collaboration with Sofia Vivanco Airaghi, a young cartographer who also works on the [https://www.antievictionmap.com/ Anti-Eviction Mapping Project] in the Mission District. This map is a device for representing the whole of our intention in building a cultural life across neighborhoods. In addition to printing a regular size of the map, we’ve blown it up to 4’ x 5.5’ and take it around to the neighborhoods on the map, inviting input. Sites on the map characterize the way culture is generated in working class communities—the barbershop, music store, the library, community gardens. Aliyah Dunn-Salahuddin, chair of African American Studies at CCSF, showed us locations for the [[The Hunters Point Riot|1966 Bayview Uprising]] sparked by the death of young Matthew Johnson by officers of the San Francisco Police Department, an event we remember from growing up in the city. We’re still adding. Most recently we learned of five streets in the Bayview, each named for a woman activist who came to prominence after the Uprising; we’ll add these streets to the map. Local artists are depicted on the map and their names border the map: Neo Ve’ave’a, artist and activist who grew up and works in Visitacion Valley and Nate Watson, director of Public Glass in the Bayview and member of Related Tactics, a collective working at the intersection of race and culture are the largest figures in the map’s borders. | Our current project is a map for residents of our region (see top of page). We created and update the map in collaboration with Sofia Vivanco Airaghi, a young cartographer who also works on the [https://www.antievictionmap.com/ Anti-Eviction Mapping Project] in the Mission District. This map is a device for representing the whole of our intention in building a cultural life across neighborhoods. In addition to printing a regular size of the map, we’ve blown it up to 4’ x 5.5’ and take it around to the neighborhoods on the map, inviting input. Sites on the map characterize the way culture is generated in working class communities—the barbershop, music store, the library, community gardens. Aliyah Dunn-Salahuddin, chair of African American Studies at CCSF, showed us locations for the [[The Hunters Point Riot|1966 Bayview Uprising]] sparked by the death of young Matthew Johnson by officers of the San Francisco Police Department, an event we remember from growing up in the city. We’re still adding. Most recently we learned of five streets in the Bayview, each named for a woman activist who came to prominence after the Uprising; we’ll add these streets to the map. Local artists are depicted on the map and their names border the map: Neo Ve’ave’a, artist and activist who grew up and works in Visitacion Valley and Nate Watson, director of Public Glass in the Bayview and member of Related Tactics, a collective working at the intersection of race and culture are the largest figures in the map’s borders. | ||

<font size=4>Can We Build a Shared Cultural Life?</font size> | <font size=4>Can We Build a Shared Cultural Life?</font size> | ||

Revision as of 16:05, 23 April 2018

Historical Essay

By Kate Connell and Oscar Melara

All photographs are copyright Sibila Savage.

More than twenty years ago we, Kate Connell and Oscar Melara, looked for a house we could afford in our native city. We were lucky to find one in the Portola District of San Francisco. We moved from San Francisco’s Mission District, a thriving Latino-dominant cultural district, to the Southeast edge of San Francisco. Intrigued with our new neighborhood and intending to spend much of our lives here, we searched the neighborhood for cultural projects to join. We didn’t find the kinds of arts organizations housed in storefronts like the ones we had left in the Mission.

The Portola District, labeled a “working class suburb,” by geographer Richard Walker does not appear on many San Francisco city maps—often, in fact, maps extend only as far as César Chavez Boulevard, just a little south of the city’s halfway mark. Southeast San Francisco makes up nearly one fifth of San Francisco. Like its neighbors, Visitacion Valley, The Excelsior and Bayview/Hunters Point, The Portola neighborhood is still largely working class, according to the census and union membership rates. Predominantly a neighborhood of color, the Portola, like the rest of Southeast San Francisco, is little known to much of the rest of San Francisco. In fact, even many of us living in the Portola know only a little about the rich cultural history and current vibrance of our three neighboring districts. City services are not abundant here. With only one cultural center, the Bayview Opera House, and minimal arts funding, we wonder how can a changing community made up of disparate communities come together? Can art help?

After moving to the Portola, we started reworking our art practice process from scratch, figuring out how to become part of the community fabric here. Workers from the city’s Department of Elections were canvassing for neighborhood garages to host election sites. We volunteered and began to learn the story of the Portola from neighbor voters. Rita and Hazel, elderly widows on our block, described a neighborhood filled with greenhouses and corrals. Hazel Laine moved to the neighborhood with her family as an infant, in the wake of the 1906 Earthquake. The Laine family camped in a corral, next to cattle destined for Butchertown in the nearby Bayview District. Hazel’s older brother ran the local gas station, charging extra to rum runners during Prohibition. African American workers from the South bought homes here, in close proximity to their jobs in the Hunters Point Shipyards. Archival research revealed the Jewish history of the Portola, a Settlement House—a welcoming community center for new immigrants, on San Bruno Avenue and two synagogues founded at the turn of the twentieth century. Gradually, we collected mental images of what geographer Grey Brechin describes as “San Francisco Incognito.”

Mobile Toolkit Needed

Coming of age as artists in San Francisco’s Mission District, our practice was informed by participation in the Latino Chicano Arts Movement, a defacto working class, social justice movement. Oscar co-founded La Raza Silkscreen Center, one of the first Latino Chicano silkscreen talleres (workshops). The Silkscreen Center produced images for the local community and posters that addressed national and international issues that residents of the Mission district identified with. Kate worked as assistant curator and artist in residence at the Galería de la Raza, teaching artmaking workshops to all ages. The Galeria’s program promoted Latino artists and included African American, white and Asian artists as well. Both organizations were housed in cheaply rented storefronts. Once established in the Portola, we realized that minus a brick and mortar site, we would need project-based tools for mobility. Flush with all the vibrant images we had accumulated through gathered stories, we settled on producing a visual vocabulary that describes the Portola.

How a Game Brought a Neighborhood Together

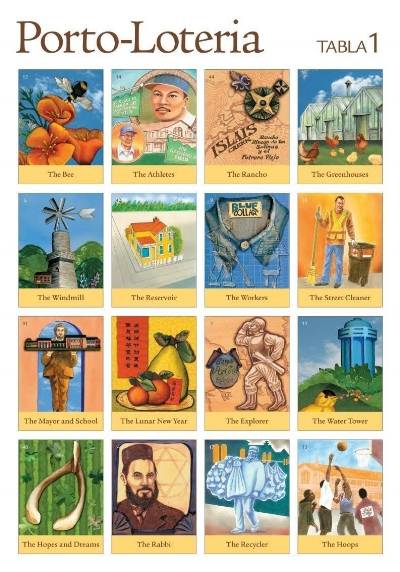

We wanted neighbors to vet the collection of images—the visual vocabulary-- and to contribute their own ideas. We settled on making a game, borrowing the form of Lotería, the popular Mexican visual bingo.

Lotería includes 54 archetypal images. We wanted our archetypes to be descriptive, inclusive and revealing. “The Recycler,” depicts a Chinese neighbor who carries her collected cans and bottles in bags hanging from a pole across her shoulders. “The Hoops” was drawn in response to an expressed concern that young African American men would be less welcome after the local rec center was remodeled. The drawing was to advocate and stake a claim for returning athletes. Driving around the neighborhood at night in December, you can see lit “parols,” Filipino star-shaped lanterns hanging in many windows, so the “The Parol” was added. “The Landmark,” was erected in the 1920s, and in the early 40s, it became San Francisco’s Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) station where Asians and Italians (and briefly, Harry Bridges) were detained. This unsavory aspect of the building’s history is kept under wraps. We drafted 53 archetypes and added a 54th box, “Make a Suggestion.” Then we played practice games. Strong responses were forthcoming—“more Italians!,” “no ‘possoms, put skunks,” “there aren’t any skateboarders around here,” (then!). “The Workers” met with approval as did “The Herbalist,” an image of Sergio Lee, the trilingual Chinese Nicaraguan businessman who also offers acupuncture.

Porto-Lotería was one third of the Portola at Play project for which we’d also enlisted musician and composer, John Calloway, and filmmaker Gustavo Vazquez. They produced original music describing the neighborhood’s history and an oral history video. Portola at Play Opening day at the Portola Branch Library drew more than 800 attendees. Prizes for the game were provided by local residents and businesses and included plants, handmade bird houses and t shirts with our Portola logo. The game was played in 3 languages, Chinese, Spanish and English. Spanish cantos or riddles were created with artist Cynthia Vazquez and students at E.R. Taylor Elementary School.

Alemany Island Project

When the Portola Neighborhood Association looked for content for a mural, Lia Smith, member of the board, proposed Porto-Loteria as the content, since residents had collaborated on image selection. Lia created a unique and thoughtful process for people who hadn’t made art or painted on a large scale to create panels for the murals. Forty eight panels were painted and combined with a painted freeway support designed by Lia’s teenage daughter to create Alemany Island at the entrance to the Portola. More than forty households participated with artists of all ages painting panels, including whole classrooms and one fire station.

It’s been twenty years since we opened our garage in the Portola for voting. Since then, we’ve worked with neighbors, local artists and organizations to make a collection of artists books that served as a reference for our branch library and included an atlas with a collection of hand-painted narrative maps. We’ve made more games, and more murals, including Our Work Life, a labor history mural installed on public buses and now at the City College of San Francisco’s campus in the Bayview. As invited artists participating in the 11th Havana Bienial, we collaborated with Laboratorio Artistico de San Agustin which operates in a neighborhood on the outside edge of Havana. Seeing other artists working in long-term engagement with their neighborhood was exciting and reaffirmed our own commitment.

Regional Focus

By 2013, San Francisco was reeling from the effects of gentrification. Suddenly, a new attack loomed—the city’s community college, a primary mechanism for working class people to improve opportunity, was at risk of losing accreditation and faced with closure. City College of San Francisco (CCSF) was the largest college in the nation, with a student body of over one hundred thousand. Kate was curator of the Library Exhibition Program there and Oscar a returning student. The Portola is home to a large percentage of CCSF students, staff and faculty. We saw the threat to neighbors and ourselves. Two of CCSF’s campuses are located in the Southeast. Our allegiance and focus shifted to a regional one: We moved to embrace all four Southeast San Francisco neighborhoods in our practice.

Moving Art House

Moving Art House came out of our activism around CCSF and our new regional perspective. Settling on a mobile cultural platform as the way to reach other neighborhoods, we designed a season of events that would include artists working in visual arts, performing arts and literature. We partnered with Richard Talavera and his Mexican Bus to site a variety of events in different locations. At the El Toro nightclub, we co-curated with John Calloway musicians that represented Southeast San Francisco’s musical history and the eighty-year history of the club. Adding games and music charlas/talks, event attendees ranged from infant to elder with teens in between. On the 5.5 Mile Road House tour, participants spontaneously added their own performances. iIn fact, every event elicited spontaneous contributions, especially in the form of dance, from hip hop to hula. We were able to commission new work from artists including poet Alejandro Muguía, musicians Mireya Leon, Adeyemi and Billy Lo and to pay longtime Southeast San Francisco artists, many of them natives of the Southeast or decades long residents like artist visual artist, Emory Douglas, once Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party, printmaker, Juan Fuentes, musicians Familia Peña-Govea and guzheng musician Shura Taylor.

Building the Art House

Since we wanted to build a cultural life within a neighborhood, and in order to reach younger participants, it made sense to create an exhibition at a key institution. The institution we had worked to save, CCSF, (CCSF’s accreditation was reinstated) was a natural fit. In the spring of 2017, Kate invited artist Emma Spertus to co-curate Building the Art House, an exhibition at the City College Library. The show included painting, drawing, sculpture, video and greenspace design. Building the Art House was located on three floors of the Library’s atrium and seen by more than six thousand viewers. Exhibiting artists ranged in age from seventeen to their 70s. The exhibition was integrated into the college’s curriculum so that students learned about their home neighborhoods in the Southeast. Artists working in physical proximity to each other met and generated possibilities for future collaboration. There are enough artists and enough work in the Southeast to easily support a second and third exhibition.

Building the Art House exhibition, Rosenberg Library, City College of San Francisco

The Cultural Map of Southeast San Francisco

Our current project is a map for residents of our region (see top of page). We created and update the map in collaboration with Sofia Vivanco Airaghi, a young cartographer who also works on the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project in the Mission District. This map is a device for representing the whole of our intention in building a cultural life across neighborhoods. In addition to printing a regular size of the map, we’ve blown it up to 4’ x 5.5’ and take it around to the neighborhoods on the map, inviting input. Sites on the map characterize the way culture is generated in working class communities—the barbershop, music store, the library, community gardens. Aliyah Dunn-Salahuddin, chair of African American Studies at CCSF, showed us locations for the 1966 Bayview Uprising sparked by the death of young Matthew Johnson by officers of the San Francisco Police Department, an event we remember from growing up in the city. We’re still adding. Most recently we learned of five streets in the Bayview, each named for a woman activist who came to prominence after the Uprising; we’ll add these streets to the map. Local artists are depicted on the map and their names border the map: Neo Ve’ave’a, artist and activist who grew up and works in Visitacion Valley and Nate Watson, director of Public Glass in the Bayview and member of Related Tactics, a collective working at the intersection of race and culture are the largest figures in the map’s borders.

Can We Build a Shared Cultural Life?

What do we want from our efforts? We envision a grass roots cultural life for our region. We want to build on the foundation created together with artists and participatory public in the Southeast through diverse endeavors including our own. We want arts funding for projects we, artists of the Southeast, determine. We want to see what our neighborhoods, our region, can yield in terms of song, poetry, performance and imagery. We want this before and in prevention of future erosion because of a lack of resources for residents and through gentrification. We want to come together and work together. We want to create an environment where the seeds of an identity and a cultural movement can thrive and produce another season. We want these vines to grow together and drop new seeds to grow and claim and proclaim space. We want to take up all the room we’re entitled to and sustain our place and shout it, show it, perform it. We want to know each other, all our generations, respectfully and vitally.