Hunters Point Uprising

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson

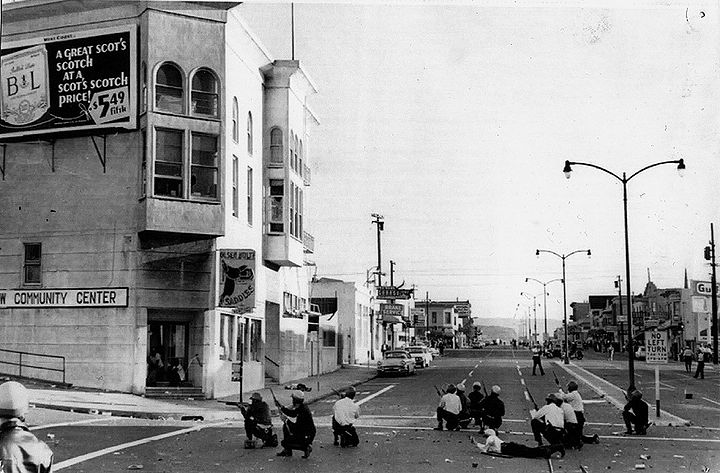

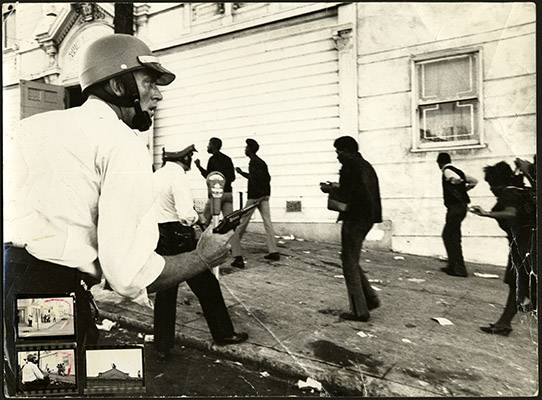

The San Francisco Police Department deployed at Newcomb and 3rd Streets, Sept. 28, 1966.

Photo: Shaping San Francisco collection

On September 27, 1966 a white police officer shot and killed a seventeen-year-old African American teen, Matthew Johnson, Jr., as he fled the scene of a stolen car. Arthur Hippler wrote a book called Hunters Point: A Black Ghetto in which, among other things, he attempts to debunk the police account of the uprising (which was published as a pamphlet called 128 Hours). This account is based partly on his.

For two hours after the shooting, a large, angry crowd milled about the site along Navy Road. The police, meanwhile, were hurrying the African Americans on the city's Human Rights Commission over to the scene. Nathaniel Burbridge of the NAACP and Tom Fleming, editor at the Sun-Reporter newspaper in the Fillmore arrived at the Bayview Opera House public meeting in the early evening where the angry crowd pressed their demands that the cop be charged with murder, a concept that was incomprehensible to the assembled authorities. By the time Mayor Shelley arrived, the restive crowd was quick to jeer him and even throw tomatoes at him. When the Mayor promised them that Patrolman Johnson had been suspended, it was too late. The lone black supervisor, Terry Francois, known as a NAACP and civil rights defense lawyer, was jeered and pelted with rocks when he appeared.

That night saw sporadic looting, rock-throwing and petty arson. "Community leaders" tried to calm the situation the next day, but Police Chief Tom Cahill issued an ultimatum: calm by noon Wednesday or massive force would be introduced. Neighborhood leaders, mostly part of the middle-aged matriarchy and/or their ministerial allies, had nothing to offer the rebels and their pleas for calm went unheeded.

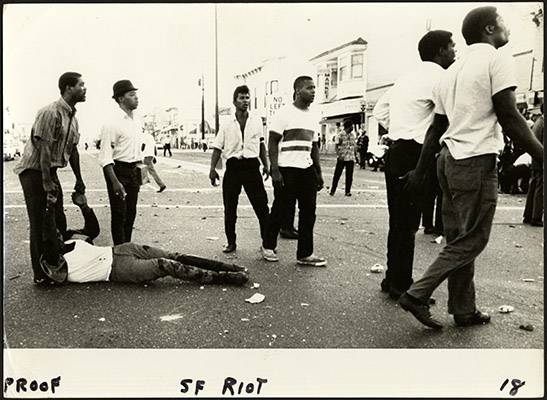

Protesters on 3rd Street during the 1966 revolt in Hunter's Point.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

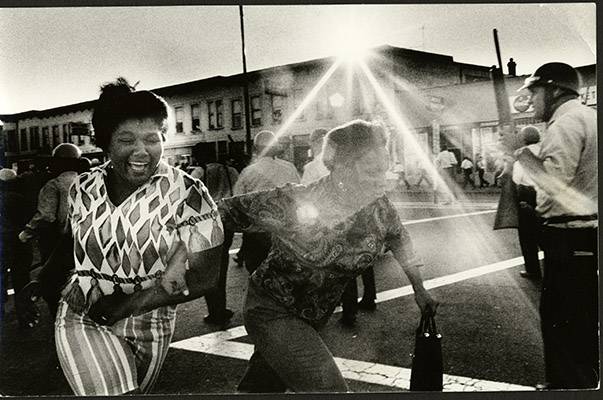

Screaming women flee the violence during the Bayview-Hunter's Point riots of 1966.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Around six in the evening, a few hours after Governor Pat Brown authorized the use of the National Guard and Highway Patrol, the police responded to alleged gunfire by opening up on the Bayview Community Center and surrounding buildings. After riddling it with hundreds of bullets the police found no gunmen or weapons but only several pre-teen kids huddling in the corner. The long suppressed anger over the abysmal status imposed on African Americans was uncontainable, but even still the action was for the most part not terribly violent.

During the next three days, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday, Sept. 29-Oct. 1, martial law imposed on the Bayview and the Fillmore, with young armed national guard troops patrolling the streets in jeeps with machine guns mounted on the back. The rebellion continued with decreasing violence, and then finally petered out. The property damage (several hundred thousand dollars) compared with riots in comparably sized cities was minimal, as were the casualties (ten civilians reported victims of gunshot wounds, no casualties among the police or other antiriot personnel)... Like most urban uprisings it consisted primarily of running around and breaking windows and sacking unpopular establishments.

Perhaps the best indication of the unreasonable magnitude of white fears at the time is the fact that, aside from long-range brick throwing, less than a half dozen assaults by blacks against whites were recorded in the course of five days of rioting... Also, the fact that the action took part in all parts of the city with sizeable black populations (the Mission district, the Potrero Hill area, the huge Fillmore district—which today includes the lower Haight and North of the Panhandle areas) and yet resulted in so few injuries indicates the targeted nature of the protests, which mostly were directed at police and unfriendly businesses.

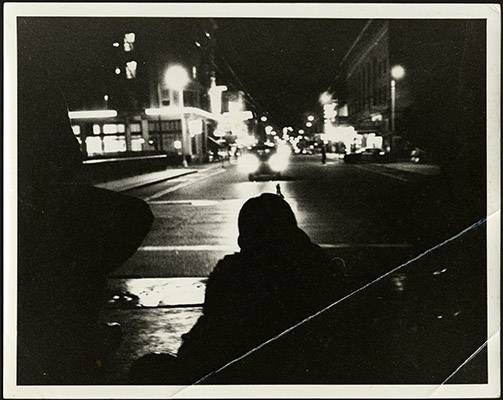

Officer aiming a gun during unrest on 3rd Street, 1966.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Riot police point guns at residents during 1966 conflict over police shooting of young man, seen here in front of the South San Francisco Opera House.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

<iframe src="https://archive.org/embed/DarrellRogersOnHPUprising" width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" webkitallowfullscreen="true" mozallowfullscreen="true" allowfullscreen></iframe>

San Francisco native Darrell Rogers (b. 1945 in the Fillmore) describes the Hunter's Point uprising from his point of view.

Video: Shaping San Francisco

The police had, until the early sixties, dealt with black youth from Hunter's Point by isolating them there. At the outbreak of the uprising, in spite of happening city-wide, the same tactic was used. African Americans, no matter who they were or what their reason for being in the area of Third Street, were either arrested or herded back up the hill. The police rank-and-file assumed a war footing, heavily framed by their essentially racist outlook. While the brass made various mediation attempts, the cops on the street saw an undifferentiated mass of hostile enemies and behaved accordingly.

<iframe width="640" height="360" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/k86MclBz7_4" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Taken from the documentary "Bay View Hunter's Point: San Francisco's Last Black Neighborhood?" In September of 1966 BVHP explodes with outrage over the police shooting of young resident, Matthew Johnson.

Video by Dante Higgins, originally posted in 2009 on the San Francisco Bay View website

Immediately after the five-day upheaval, many Hunter's Point residents hoped that it would lead to greater solidarity among community groups. Actually the opposite occurred: greater community disintegration resulted. This was reinforced when the insurance industry refused to underwrite the losses incurred by business owners in the Bayview Hunter’s Point area. The general belief that "nobody cares" and "it's too late to do anything" became widespread. Automatic weapons, portable artillery, and federal troops, i.e. military occupation, offered a vivid demonstration of how far San Francisco would go in the attempt to contain black rage. Very few community organizations continued functioning in Hunters Point immediately afterwards, though they began to re-emerge in the following years. Meanwhile, the Hunters Point Uprising itself disappeared down the memory hole.

Dr. Nathaniel Burbridge, Rev. G.L. Bedford, and Mr. Bill Bradley at a press conference during the civil rights movement in the mid-1960's.

Photo: courtesy of African American Historical and Cultural Society, San Francisco, CA

A Shaping San Francisco Public Talk commemorated the 50th anniversary of the Rebellion, and featured several other video clips.