Working at Ampex

"I was there..."

by Lee Felsenstein

Ampex corporation offices in Redwood City.

Photo: Pretzelpaws via wikimedia commons

I scouted the want ads and saw that Ampex Corporation (owners of the tape recording market) was hiring technicians. I typed up a short resume of my work experience to date. I estimated that I was about five years ahead of my fellow students in my electronics knowledge and resolved to complete my degree within that time period.

Ampex tape recorder internal workings, 1965.

Photo: Gregory F. Maxwell, via wikimedia commons

40 miles away in Redwood City, I applied at Ampex for a technician job and submitted my resume. The interviewer looked at it and said, “this looks more like a junior engineer than a technician. Would you be willing to take a test?”

Would I! What had I spent years in school learning to do! I emerged from the multiple-choice test an hour ahead of schedule to their surprise, and was sent to what I understood was my second choice—an undistinguished building named the Special Products Division, for an on-the-spot interview.

There I was shown a diagram of a small circuit—a touch-sensitive pushbutton sensor—and asked to explain its operation. Using knowledge from my electronics hobby work I walked smoothly through that circuit—my interviewers commented that no one had ever done it that fast.

I was hired as a Junior Engineer (one with no degree) at 6 dollars an hour. Much later I found out that this was the same salary my father was earning at the time. Thus, in January of 1968, I found myself no longer a student but an engineer, albeit a junior one. As a depressive, I could not experience delight, showed up consistently late for work (making sure to leave after everyone else), never unpacked my furnished apartment, and cooked the same dinner for years.

As I eventually discovered, I had landed not as I had supposed in the second-best available job but in the best by far. I had wanted to work in the “Glass Palace” at 401 Broadway, Ampex's flagship building, and work with video (Ampex had invented the video recorder). Instead, I was in a nondescript building on the edge of the Ampex campus. While a division at Ampex was typically 3,000 to 5,000 people, the Special Products Division numbered only 150. Its purpose, I was told, was to design and build from the ground up any oddball product that a customer could pay for. We had a manufacturing shop, a purchasing office, marketing department and a good complement of engineers.

What I discovered decades later was that SPD was Ampex’s “spook shop” which served the government developing secret products. A few years before, it had developed the VHS video cassette recorder, built to ride in a plywood drone over the Soviet Union recording pictures from a high-resolution camera onto a videotape cassette. When the mission was done the cassette would eject and be dropped in a capsule under a parachute, to be snagged by military aircraft patrolling in wait. The drone, its purpose served, would fly on until it ran out of fuel over the ocean and crashed.

This was done without microprocessors or almost any digital electronics—quite a feat of engineering, as I learned from my former supervisor almost 50 years later. It also turned out that Ampex had no idea what to do with the VCR as a product, eventually giving it away to Japan Victor Company (JVC) who brought it successfully to the civilian market. Ampex received almost no benefit from that transaction, I later discovered.

I worked on the development of high-speed cassette tape duplicator systems for the first year of my employment. My work was successful and one day in 1970 I saw a pile of the units I had designed stacked in a hallway—Ampex used them in its music cassette production business. I realized how much money was flowing to Ampex through my work, and it somehow came as a shock to me.

Ampex Special Products Division had secured a contract to design, build, and install several instructional systems at colleges. Their purpose was to bring “interactive” audio lectures with still video illustrations to students through terminals called “student positions”—in effect, vending machines for instruction.

The technology is quaint today—it could all be handled with DVD players—but that digital technology was not yet developed. The “Pyramid” system (its name a convoluted synthetic acronym) was to be installed in the bowels of the client university and wired to "student positions” across the campus. Lectures would be played from specialized tape recorders/players wired to each position.

The system could display still video images and present quizzes. Commanding it all and responding to the quiz responses was the very latest in low-cost computation—a Data General Nova 1200 minicomputer. It cost $10,000 and could sit comfortably on a table top, though it required a terminal (a Teletype Model 33 or something equivalent) to allow any interaction at all. Interfacing its innards to our hardware was the job of a purpose-built box which connected to other purpose-built boxes. It was industrial electronics, with which I was to become quite familiar.

My title was “MPD”—Maintenance of Product Design—the guy who had to deal with problems that came up in use, which entailed begging for help from the engineers who had designed it and who generally wanted me to go away.

We had a training course on the innards of the computer, held in our demo room where the development system was installed. I had been in that room many times before, but this time when I sat down in an instructional environment my internal demons threw my mind into sleep mode. I retained almost none of what was presented, nodding off constantly. My notes were useless.

One of the effects of depression is that it motivates the subject to seek different surroundings in the hope that things will resolve. This leads to a lot of relocation, no doubt a major factor in the numerous stories of men who move restlessly about, never holding a job for a long time and unable to integrate into the community.

Many such wanderers will self-medicate with drugs or alcohol, which I fortunately never did. I retained my affiliation with the Berkeley Barb, driving up to Berkeley every Wednesday night in my cheap suit and tie, cutting an incongruous figure among many of the subjects of my reporting. When someone asked me, “How do you do it, Lee, moving between two worlds like that?” I replied, “Don’t you know there’s only one world?”

Then, in the spring of 1969, my landlords told me that their son would be moving into my garage apartment and that I should find another place. I took the opportunity to move to San Francisco, commuting by train for about a month before I gave notice to Ampex that I'd be leaving. I was going to work for the Berkeley Barb.

Revelation

Back at Ampex in 1970, I found that Special Products had landed a big contract which would throw me directly into contact with the computers I had avoided ever since my high school computer club experience ten years before. At work, I was assigned to attend a training session on the BASIC computer language, an English-like language very popular with first-time computer users. These days (or even a few years from then) one would learn it using a personal computer, but as they did not yet exist, I had to drive to a “service bureau” in a nondescript building in an industrial park.

There we were instructed by young men in three-piece suits who seemed quite impressed with themselves. The computers were IBM but they were nowhere to be seen—access was over a mysterious “network.” Our positions were Selectric typewriters that worked as remote terminals.

We learned how to create and access documents and store them in invisible locations by naming them. We learned the hierarchy of files. Each of us had a private storage area in the computer, but by prefacing our file names with different numbers of asterisks we could grant access to wider and wider sets of users. Three asterisks meant a file could be accessed by anyone on the system.

At one point the terminals stumbled and began responding more slowly than usual. Our instructor flaunted his knowledge by saying, “That’s because they’ve turned off the computer in Los Angeles and transferred our job to the computer in Kansas City.” Big computing could still impress us little folk.

After the first two days the secretaries enrolled in the class were sent home and for the rest of the week the remaining engineers were taught how to write BASIC programs. This time I found myself not subject to depressive narcolepsy and began to connect what I learned to my explorations outside of work.

The fact that the computers were networked and could be accessed from anywhere on that network meant that the system was not constrained by geography. And the fact that files could be made accessible to different groups anywhere on the network meant that it could be a matrix for the growth of communities of interest. My forlorn “network bulletin” could someday find a home on such a system! It was a form of decentralized publication—the nonhierarchical communication system for which I had been searching!

HS 100 deck by Ampex.

Photo: Telecine guy at wikimedia commons

It finally struck me that the tool I needed to support the formation, growth and ongoing life of communities of interest would be a network of computers! Then reality set in. Where would I get a computer? How would I create a network? It seemed impossible, but the vision remained. I was used to thinking in that mode.

Making Something Happen

At Ampex one day in 1971 we found the lunchroom closed for an emergency stockholders’ meeting. The company had encountered hard times and had been taken over by Wells Fargo Bank, according to rumors. Soon the layoffs began. I was given an assignment which frightened me—to assemble the components and do the programming for a bare-bones demonstration version of the Pyramid system. It was that or leave.

The hardware was no problem. I got one of each of the elements from stock—the student buffer tape unit, the master tape unit, the matrix switch, the student position control panel, the computer, and the computer interface unit. Fortunately, our video people handled the responsibility to make the 14-inch, free-standing video discs work with it, much to my relief.

I set them all up in a clumsy arrangement on the floor of the “bull pen” shop area near the video disc area and then opened the manual for the minicomputer to learn how to program in machine language (the sparse language specific to that computer, working through an “assembler” program that recognized a very limited vocabulary).

One of the first things I had to do was to write code to make the terminal work under program control. I could already use it with the assembler program to write the code. Now I had to write the code that made the Teletype print what my program produced (and the code to read data from the keyboard). The manual gave an example of a very crude program that used “in-line code,” through which the program commanded the computer to send to the Teletype the contents of a specific location within the same program. The program segment that made use of this routine had to store the character to be printed into that specific address. Get the address wrong and you would fatally clobber the program.

With trepidation, when I felt my code was ready, I entered the ASCII code representing upper-case “A” into the location using the front panel switches of the idling computer. I then held my breath and pressed the “run” switch to start my program.

With a loud “CHUNK!” the Teletype spasmed into action, deftly rotating and lifting its print head and unleashing a paddle to swat it into the ink ribbon and the paper beneath, returning immediately to its resting state within a tenth of a second. There, on the paper, stood an upper-case “A”—exactly as I had intended!

It was a transcendental experience—I was on my way! I wrote and wrote program routines, trying to keep their names arbitrarily to three-letter Jewish first names (MAX, MOE, IRV...). This qualified me, I can now see, as a hacker, taking a playful approach to writing code.

After perhaps two weeks of such labor I could make my tiny orchestra of units perform, commanding a transfer through the 12- button keypad, watching the master and student tapes move forward or back to the right spots on their tape drive, setting up the matrix switch to route audio from the master to student units, initiating the high-speed transfer and then releasing the master unit connection.

Finally, the student tape unit played the transferred audio through the earphones when I pressed the "run" button on the student control keyboard. My demo was to the division CEO, who came back alone to the bullpen to see. I put the system through its paces and nothing went wrong. The CEO mumbled in his typical fashion, “I’m impressed.” He turned to leave, then returned and repeated “I’m impressed,” apparently for emphasis. I still had a job.

Toward the end of 1971 the system project was transferred to the VideoFile division, which had been developing information retrieval systems using videotape technology. For the final two weeks of my employment at Ampex I commuted to the VideoFile building in Sunnyvale. I had tendered my resignation to take “educational leave.” I would be resuming my interrupted education at Berkeley starting in January of 1972.

(Ed. Note: In the process of excerption some words defined in previous parts of the book appear undefined and the author recommends reading the whole book un-edited to fully understand his meaning.)

previous article • continue reading

Excerpted with permission from:

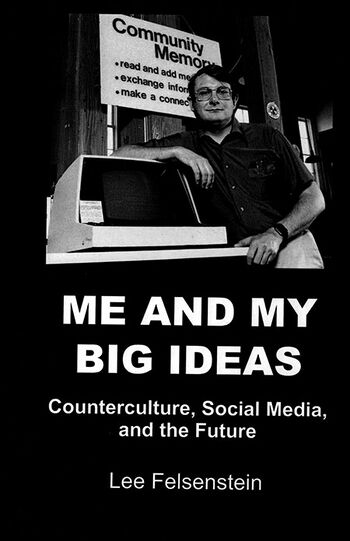

Me and My Big Ideas: Counterculture, Social Media, and the Future

by Lee Felsenstein

published by FelsenSigns