Trial of the Rincon Annex Murals

Historical Essay

by Gray Brechin

Rincon Annex lobby, restored and open 24 hours but no longer a post office. The murals encircle the upper walls of the lobby.

Photo: John Horn

On the morning of May 1, 1953, the House Committee on Public Works convened in Washington, D.C., to debate the destruction of one of the largest and most expensive artworks ever commissioned by the federal government.(1) The artist Anton Refregier, according to Republican Representative Hubert Scudder of Sebastopol, California, had foisted upon the American taxpayer propaganda designed to slander the state's pioneers and convert patrons at San Francisco's main post office to communism.(2) In its daylong deliberations, the committee put history, as well as art, on trial.

Refregier was too modern, according to his accusers, for whom "modern art" was an imprecise but pejorative term covering form, or content, or both, as it served their purposes. Modern art was alternately incomprehensible and reprehensible, degenerate, or left-wing. Because they admitted at times that they were not sure just what it was, they felt safer saying what it was not ; modern art was not academic and thus did not support the social order and the state. In his subject matter, at least, Refregier had transgressed the official canon.(3)

To comprehend that day's strange events, one must understand not only the paranoia of the cold war but the near-Confucian reverence descendants of the California pioneers lavished on their ancestors. Ever since the Bear Flag Revolt of 1846 Anglo-Californians had envisioned their land as a mountain-walled principality, more nation than state. By California's fiftieth anniversary, in 1900, press and orators often compared the argonauts of 1849 to the founders of Rome. Artists were commissioned to pay them homage. In 1905 Daniel Burnham proposed a colossal monument for the summit of Telegraph Hill. For the 1915 world's fair, a permanent 850-foot Tower of the Pioneers was planned for Land's End. The tower was scrapped for lack of funds, but the exposition, as Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane noted, was itself a monument to the superhuman valor and energy of the state's early settlers.

That the West was a place of unusual rapacity and violence and gold more a curse than blessing had been noted by visitors from the opening of the Gold Rush. The banker William Tecumseh Sherman observed sourly in 1856 that "the very nature of the country begets speculation, extravagance, failures, and rascality." Frederick Law Olmsted told San Franciscans in 1866 that a great public park would help to "overcome the dead weight of indifference to all municipal improvements which is characteristic of the transient speculative class." Joshua Speed, a close friend of Abraham Lincoln, recorded while traveling in California in 1876 that money was the universal yardstick of worth: "They measure everything by the gold standard, men as well as mules. You never hear of Mr. Smith as a good man, or Mr. Brown as an honest man, or Mr. Jones as a Christian, but Mr. S has twenty thousand million and so on. The more he has, the better he is—and it matters not how he got it, so he has it."(4)

Such harsh judgments were drowned by the percussion and brass of official civic mythmaking. The industrialist Joseph Donohue Grant, son of a pioneer dry goods magnate, answered all would-be knockers in his 1931 autobiography. Of empire builders such as his father, he wrote:

Alert, high-spirited, warmhearted—those who constituted the population of early San Francisco were gentlemen adventurers outshining in brilliance similar coteries in older communities. What a libel to speak of a greed for gold bringing such men to California! They came as searchers after larger opportunities, to a new land abundantly rich because they made it so. No more openhanded people ever lived.(5)

In the heroic generosity, intelligence, and virility of the pioneers, Grant and his set found ample proof of the survival of the fittest and thus of their rightful place at the apex of the West's financial and social pyramid. In their traditional role as patrons, such aristocrats expected artists to reflect and support their certainty according to the academic tradition, in which history was depicted as a triumphal march undeterred by border skirmishes. Among a growing number of artists who rejected that tradition after the trauma of the Great War was Anton Refregier.

Although even the depression could not shake Grant's granitic confidence, the foundation myths crumbled for millions of Americans who suddenly found themselves near starvation in the Promised Land. By 1934 the socialist Upton Sinclair's grassroots campaign for governor had grown so serious that an unprecedented (and pioneering) smear campaign was required to defeat him and to elect the unpopular Frank Merriam in his place.(6) In the same year, conditions along the waterfronts of the West Coast grew so desperate that longshoremen walked out on what little work they had. Governor Merriam placed San Francisco under martial law and sent tanks to patrol the Embarcadero. The Pacific Maritime Strike culminated in a pitched battle in San Francisco between pickets and police. Two workers were shot and killed in a fusillade at the foot of Rincon Hill. Within days, forty thousand men marched silently down Market Street (Fig. 23) in one of the largest funeral processions in city history.(7)

The general strike that followed shut down the city for four days, precipitating a rain of phone calls and telegrams to Washington claiming that revolution had begun on the Pacific Coast. The alarms helped persuade President Roosevelt and his brain trust to accelerate their public works programs to short-circuit any such possibility. No one has ever inventoried the New Deal's legacy of public works for the Bay Area alone, but it would include paved roads, sewers, forests, parks, schools, and theaters, as well as a myriad of federal art projects.(8)

Prior to the crash, virtually all public art had endorsed the benignity and legitimacy of the American Dream. No market existed for artists who might question it. But in 1934, in the depth of the depression, President Franklin Roosevelt opened a window for those who might dissent, giving them both patronage and exhibition space without precedent in the United States.

Roosevelt's experiment in federal art sponsorship began at the suggestion of his Groton and Harvard classmate George Biddle. A painter himself, Biddle first proposed to the president in 1933 that the government provide relief for American artists. Biddle hoped to create the seedbed for an American renaissance. He later wrote of the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project: "Its credo is that if one creates a cultural background, art will follow. It wasn't Michelangelo who created the 15th century but the 15th century that created Michelangelo."(9) The conservative Commission of Fine Arts, created by Congress in 1910 to advise the government on artistic matters, recommended against Biddle's proposal in a report to the president, fearing trouble from modern muralists who professed "a general faith which the public does not share," one that ignored "the established tradition . . . fostered by the American Academy at Rome."(10)

The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and the other programs that followed it initiated controversies that outlived Roosevelt by many years as a minority of left-wing artists tested the First Amendment and reactionaries, in turn, cited the right of taxpayers not to be insulted or indoctrinated by "radicals." Guardians of tradition and morality like the National Society for Sanity in Art, founded by the Chicago socialite Josephine Hancock Logan, along with its regional affiliates and the Hearst press, carefully scrutinized the new public art for symptoms of modernist "decadence" or the un-American content usually equated with it.(11)

The federal art projects never received the popular support Roosevelt himself enjoyed. The president created them by executive fiat, leaving representatives to deal with their irate constituents.(12) Nor did Biddle help. The aristocratic artist enjoyed needling powerful domestic opponents: "The most serious threat to the success of life of the Project," he wrote after much experience, "is the high emotional level and the low mental caliber of our Congressmen."(13)

Biddle looked to Mexico for a model of government art patronage, but in doing so he ignored the radically different political climate of the neighboring nation. By 1934 privately commissioned works by two Mexican muralists had amply demonstrated the uproar that allegedly subversive subject matter could cause in the United States. In 1930 José Clemente Orozco completed his mural Prometheus in the Pomona College dining hall, despite vigorous attacks from college trustees and local newspapers alarmed by what they perceived as their revolutionary content. Four years later, Nelson Rockefeller ordered stripped from the lobby at Rockefeller Center Diego Rivera's mural Man at the Crossroads, whose numerous unorthodoxies included a portrait of Lenin as well as syphilis spirochetes swimming toward a swank dinner party in what was intended to be a cathedral of capitalism.

On an extended visit to paint murals in San Francisco during the early 1930s, Rivera had strongly influenced many of the artists whom the government would later commission to decorate the walls of the new Coit Memorial Tower on Telegraph Hill. Edward Bruce, head of the PWAP, hoped that the tower's murals would serve as a pilot demonstration of how federal patronage could enrich the nation's cultural life. Their theme was "Aspects of Life in California, 1934"—a bad year, as it turned out, for officially sanctioned subject matter.(14)

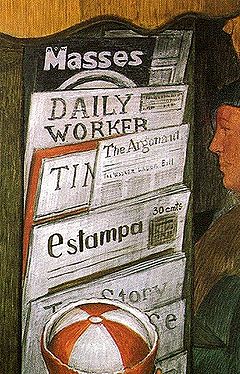

In mid-February, the San Francisco Artists' and Writers' Union met at the unfinished tower to protest "the outrageous vandalism and political bigotry" represented by the destruction of Rivera's New York mural. Their activism only drew attention to what they themselves were creating. Reporters from the major press quickly discovered subtle heresies in the tower's murals meant to undermine the national faith. In a large street scene, for example, Victor Arnautoff had replaced the San Francisco Chronicle with the Daily Worker and the Masses. Browsers in Bernard Zakheim's Library were choosing Das Kapital rather than The Wealth of Nations. Worst of all, Clifford Wight had included, without permission from the regional PWAP chairman, Dr. Walter Heil, a hammer and sickle as emblematic of one economic choice available to Americans in the 1930s.

In his capacity as director of the M. H. de Young Memorial Museum, Hell was unaccustomed to the controversies of art in action. He wired Washington that "editors of influential newspapers . . . have warned us they would take [a] hostile attitude towards [the] whole project unless these details be removed." Edward Bruce responded that he hoped the artists "don't fool around with this Socialistic thing any longer," and advised Hell to "wipe the damn painting out of the Tower."(15) Making good on its promise to Heil, the Hearst-owned San Francisco Examiner carried a nationally syndicated photograph of Wight's symbol crudely spliced onto Zakheim's Library.(16) The doctored photo appeared on July 5, 1934, the day the strikers were killed at Rincon Hill. So intense did the controversy become, and so closely linked was it to the events on the waterfront below Telegraph Hill, that the city Park Commission ordered Coit Tower locked, ostensibly to prevent vandalism. It was reopened on October 20, 1934, after passions had cooled. By that time, Wight's symbol had mysteriously vanished.

Evelyn Seeley, reporting on the Coit controversy, felt it was a tempest in a teapot. "In the main, [the artists] presented California as powerful and productive, its machines well-oiled, its fields and orchards bountiful, its people happy in the sun." In a comment prophetic of those made in the thick of the Rincon Annex controversy, she added, "They have left out of the picture, as some realists have mentioned, such aspects as the Mooney case, or strikes or lynchings."(17)

The Coit Tower controversy did not end government patronage. Rather, New Deal programs proliferated in the years that followed. Of the art bureaucracies that followed the PWAP, the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture (known simply as the Section) offered the most prestigious and lucrative prize.(18) Created by executive order of Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau on October 14, 1934, the Section would ensure high-caliber work in public buildings by selecting artists in juried competitions. In 1940 a Section jury chose Anton Refregier, of Woodstock, New York, from among eighty-two contestants, to decorate a new post office in San Francisco. The government agreed to pay Refregier $26,000 to design and paint a chronological history of the city in twenty-seven panels totaling 2,574 square feet. A delighted Refregier told reporters that he had worked five solid months preparing his designs. What he did not tell them was that he would paint just those "realist" subjects that Evelyn Seeley said had been left out of Coit Tower.

A strong-minded outsider, Refregier also told the Chronicle when he arrived in San Francisco that he wanted to paint the past, not as a romantic backdrop, but as part of the living present, a present shaped by the trauma of depression, strikes, and impending war. He did not, he added, believe that the miners of 1849 wore gardenias, and he saw no reason to paint them as if they did.(19) In these desires and beliefs Refregier was modern, differing sharply from both working-class patriots and ancestor-proud patricians such as Joseph Donohue Grant. World War II, however, interrupted the Rincon Annex project, while Roosevelt's death virtually ended the brief experiment in federal patronage. By the time Refregier returned to San Francisco in 1946, the Section was being phased out and responsibility for its outstanding projects transferred to the Public Buildings Administration.

Refregier's highly ambitious program was traditional enough. He envisioned representing the entire span of human civilization in the brief history of San Francisco. In the cycle as originally conceived in 1940, the artist had intended to begin with a California Indian creating a primitive work of art and to proceed through a sequence of conflicts to the 1939 Treasure Island world's fair celebrating peace in the Pacific. Following the armistice, he changed the last panel to a three-part composition representing the war, the Four Freedoms, and the founding of the United Nations. Refregier had covered the latter event in San Francisco for Fortune magazine.

Controversy began before the Rincon paintings were finished.(20) The Catholic Church protested that a friar preaching to Indians at Mission Dolores was too fat; Refregier slimmed him. In 1947 the Public Buildings Administration ordered Refregier to take President Roosevelt out of his panel The Four Freedoms. The artist claimed that a Republican Congress had initiated a campaign to discredit the late president and the legacy of his New Deal.(21) Although he called on the people of San Francisco to support his refusal to carry out the order, he eventually complied.(22) His troubles had only begun.

By the spring of 1948 the Veterans of Foreign Wars were protesting Refregier's depiction of the maritime strike and the funeral for the strikers killed across the street from the Rincon Annex Post Office. Fourteen years after the strike and killings, those events were still raw in local memory. According to the VFW, the strike leader rallying massed workers in Refregier's painting appeared to be the suspected communist Harry Bridges. He points accusingly at a hiring boss taking bribes in the notorious "shape-up system" that prevailed before the strike won longshoremen the right to a union hiring hall.(23) The artist may as well have tossed gasoline onto a guttering campfire. "The stories in the Hearst press," he later wrote, "brought out gangs of hoodlums who were constantly under my scaffolding and I no longer worked after the sun set."(24)

'Refregier's controversial pro-labor mural. The panel, based on an Otto Hahn photograph, shows men, at left, begging for jobs from a corrupt hiring boss. The figure at center could be Harry Bridges organizing the union, and the figures at right mourn two strikers killed by police on "Bloody Thursday," July 5, 1934, the day the police fired at strikers on Rincon Hill.

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo: John Horn

Despite a national outcry by artists and labor unions, the Public Buildings Administration ordered the offending panel covered until specified changes were made. Refregier wrote that "it was a most telling coincidence that on the day the men came to cover up this panel, I was at work on a mural depicting the burning of the books by the Nazis. [25] He told the People's World that "this attack is clearly a part of the whole thought control campaign" to censor history. [26] The artist was supported by the Congress of Industrial Organizations and the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union, which denounced the "Hearst-inspired attempt to suppress the work of art."(27) In Refregier's paintings, instead of the standard vindication of the status quo, union members found the theme of class struggle. On May 14, 1948, they joined artists in a picket line at Rincon Annex to defend the murals.

Artist Anton Refregier and C.I.O. longshoremen union members carrying a banner in protest for the covering up of a section of a mural at the Rincon Annex Post Office, May 14 1948.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

When the painting was unveiled with minor changes, the Grand Parlor of the Native Sons of the Golden West declared itself unmollified. The attorney Waldo Postel announced that the NSGW would scrutinize the artist's background as well as the "Marxian interpretation" of the entire cycle. True to his word, Postel analyzed Re-fregier's work closely and noted numerous transgressions. He accused the artist, for example, of "memorializing the Federal Art Program of 1932-41 [in the panel Cultural Life], although what connection it had with San Francisco's cultural history I don't know."(28)

Refregier's murals elicited enmity in high places. On July 18, 1949, Representative Richard Nixon of California responded to a concerned American Legionnaire:

As to whether anything can be done about the removal of Communist art in your Federal Building [Rincon Annex] . . . at such time as we may have a change in administration and a majority in Congress, I believe a committee should make a thorough investigation of this type of art in government buildings with the view to obtaining the removal of all that is found to be inconsistent with American ideals and principles.(29)

As cold war paranoia grew, so too did a passionate debate over what some felt to be subversive themes concealed in public art sponsored by the Roosevelt administration. Michigan Representative George Dondero, in particular, launched a campaign against all that was "modern" in art, a term which he defined as "communistic because it is distorted and ugly, because it does not glorify our beautiful country, our cheerful and smiling people."(30)

The Republican Party in 1953 took control of both the White House and the Capitol. With Richard Nixon as vice president and Representative Dondero as chairman of the House Committee on Public Works, Congress prepared to undo the New Deal and to roll back the red tide of modernism in Nixon's home state.(31) Anton Refregier's murals were the first works to be tried for themes "inconsistent with American ideals and principles."

Representative Scudder opened the hearing by telling his committee that Refregier had been born in Moscow and that his office had been flooded with complaints from the American Legion, Daughters of the American Revolution, Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Sailors' Union of the Pacific, and other patriotic organizations. The Young Democrats of San Francisco charged the murals with being "little short of treason." The Society of Western Artists, a regional affiliate of Logan's Sanity in Art, (32) declared them "artistically bad, historically absurd, and politically corrupt." A letter from the California Department of the American Legion expressed its members' concern that the murals would expose thousands of school children who toured the facility to scenes that unfairly depicted what it believed was "the true history of our State."

The operative statement that recurred, verbatim, in nearly every protest that Scudder read into the Congressional Record was that "said murals do not truly depict the romance and glory of early California history, but on the contrary cast a most derogatory and improper reflection upon the character of the pioneers, and the other murals are definitely subversive and designed to spread communistic propaganda and tend to promote racial hatred and class warfare." (emphasis added).(33)

Scudder then yielded the floor to California Representative Donald L. Jackson, who insisted that his testimony "should not be construed as representing the results of an investigation" by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), of which he was a member. Jackson's seven-page account of Anton Refregier's participation in communist front and peace organizations took forty-five minutes to read. The painter, he said, had defended such fellow travelers as Dalton Trumbo, Pablo Neruda, Harry Bridges, and the Rosenbergs and, as a member of the suspect American Peace Crusade, had once given a reception to honor the Los Angeles painter Charles White, "a Negro artist."(34) He had taught at the John Reed School in New York and the California Labor School in San Francisco.(35) The list went on.

Under questioning by Chairman James C. Auchincloss, Congressman Jackson admitted he had not seen the San Francisco murals but asserted, "If they were in the Capitol of the United States, I would join in protesting them." When Scudder revealed that Refregier had won the Section competition because of favorable votes from the artists Victor Arnautoff and Arnold Blanch, Jackson read their HUAC dossiers into the Record. Philip Guston had favored another entry and was spared embarrassment.(36)

Congressman Scudder then detailed, panel by panel, what he found objectionable in Refregier's cycle. (37) California Indians were depicted as vigorous and strong, the Spanish and English explorers as warlike and conquering. The monks building Mission Dolores appeared cadaverous in one panel and big-bellied in the next, where their Indian wards appeared to be starving. The pioneers on The Overland Trail also appeared "cadaverous and soulless." In Discovery of Gold, the miners seemed to thank God for the metal they had found, suggesting that Californians were materialists, as the communists claimed. In the panel showing the building of the transcontinental railroad, Scudder thought Refregier was saying that the Chinese had done most of the work—which was, in fact, common knowledge in California.

Gold miners, giving thanks to God for their good fortune?

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo by John Horn

Building the Railroad. Representative Scudder protested that the mural's portrayal of the Chinese workers "would give he impression that they were brought over more as slave laborers than anything else."

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo by John Horn

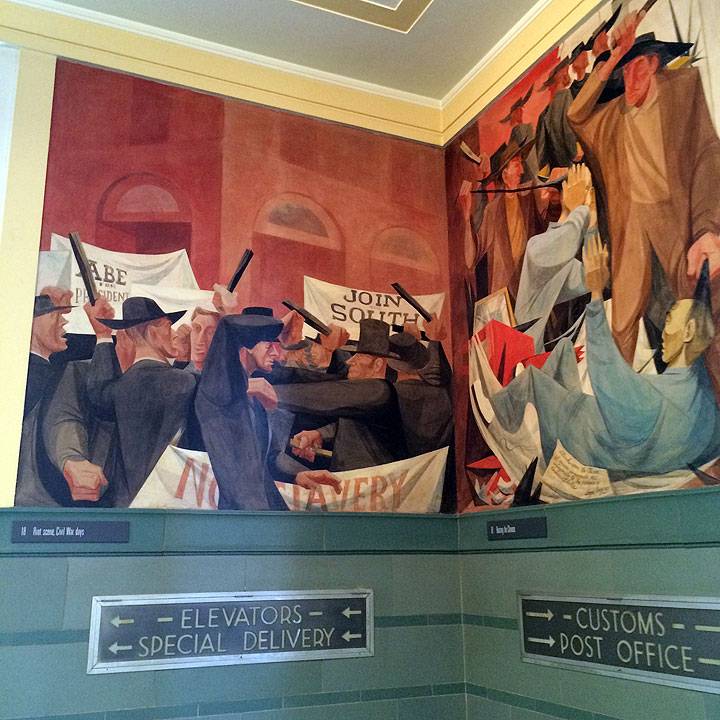

In a dark corner, Refregier had painted two riots. Scudder felt that The Civil War unnecessarily depicted regional strife in a public building. In the adjacent Sand Lot Riots, Refregier had shown Irish laborers beating the Chinese. Scudder protested, "I do not believe that this ugly scene had a bearing on the development of California. . . . If it did happen, it is similar to the riots that happen every day in some country." Furthermore, the congressman complained, the rioters were sporting "peculiar clothes and funny hats which were not commonly worn in the days of early California." He felt that the depiction of the 1906 earthquake unnecessarily aggrandized tragedy and implied that it took a great disaster to make Americans work together.

Civil war riots (left), and anti-Chinese sand lot riots (right).

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo by John Horn

This panel depicts the Preparedness Bombing in 1916 and the railroading for Tom Mooney and Warren Billings to jail in its aftermath.

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo by John Horn

Scudder inexplicably paid little attention to one panel that conflated the mysterious bombing of a Preparedness Day parade in 1916 with the perjured testimony of witnesses that subsequently sent labor leaders Tom Mooney and Warren Billings to prison for the crime. His omission was curious, for the Mooney trial had provoked an international furor and long served as a flash point in confrontations between conservatives and liberals. Scudder moved on, instead, to the panel that had begun the brouhaha. The Waterfront—1934 showed "strikes and various other disturbances" that were not, the congressman charged, "the things that make California great." Nor did the men in the next panel, which showed the building the Golden Gate Bridge, resemble those he had observed at work on the structure. Scudder also repeated the allegation of the Hearst newspapers that Refregier had included in The Four Freedoms a figure resembling Gilbert Stanley Underwood—the architect of the post office—with "long mule ears."

The Four Freedoms. Alleged mule ears are the green garlands at right.

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo by John Horn

Scudder's final criticism was demonstrably mistaken on three points: the controversial figure was not Underwood, it occupied the adjacent United Nations panel, and the suspect "ears" were, in fact, a garland of laurel leaves Refregier had seen decorating the stage when he covered the signing of the U.N. charter for Fortune magazine. Scudder's confusion suggested that he, like Representative Jackson, had never seen the murals that he sought to have destroyed.(38) He summed up by saying,

There seems to be nothing in these pictures that would be anything but depressing. I do not believe that one of the murals conveys a smile, or the indication of a smile, or contentment, or encouragement. What the artist was endeavoring to convey is beyond me, except that we are unemotional and unsympathetic in the development of the State of California and the building of the West.

The attack on the murals continued after the lunch break when Fred Drexler, a retired newspaper reporter, testified that a postal worker at Rincon Annex had told him that "the Government ought to increase his pay to make up for his suffering in seeing these murals." Gordon A. Lyons, the department adjutant of the American Legion of California, submitted more demands for the removal of the murals, from organizations ranging from the Associated Farmers of California to the South of Market Boys Association. The discerning eye of the attorney Waldo Postel had meanwhile discovered heresies in The Four Freedoms more subtle and dangerous than Refregier's tribute to the New Deal art projects; Postel informed the committee that "the head of the family there shown wears a red tie, while the boy reads a large red-covered book. The predominating color in these three panels is red." He concluded: "These murals are definitely subversive and designed to spread communistic propaganda."

Late in the afternoon Congressman John Shelley of San Francisco rose to rebut his colleague from Sebastopol. As he spoke, Shelley—who was to be elected mayor of the city in 1964—gradually established his bona fides. He was a descendant of Irish pioneers, his father was a longshoreman, he himself was a member in good standing of the Native Sons of the Golden West, with which, he added, he respectfully disagreed on this one issue. He was also active in the labor movement. His grandfather, he said, like most California men of the time, had worn one of the "funny hats" to which Scudder had objected. Moreover, as a Catholic, Shelley found nothing objectionable in Refregier's paintings, nor did any prelate that he knew. Similarly, he could testify to the reality of the waterfront shape-ups and the payoffs to corrupt gang bosses. Shelley believed that mature citizens of a democracy were entitled to see and hear provocative subject matter: "The cold factual portrayal of history . . . may be pleasing to some and repugnant to others, but if it is factual you cannot change history or a picture of history or a portrayal of it by saying 'But I do not like that.' If we get into that, Mr. Chairman, then we are definitely contributing to thought control and trying to build a Nation of conformists."

Scudder riposted that Refregier could have shown the grape industry, stock raising, or industrial development: "We know the history of the world has not always been sweet, but I do feel that we should glorify the best in life." Shelley shot back, "Mr. Scudder, I do not wish to argue with you about it, but I can certainly appreciate your feeling about wishing to portray the sweet things, because by nature you are so sweet and generous yourself."

Congressman William Maillard, scion of an old San Francisco family, took the stand next. Whereas Shelley had spoken for labor, Maillard spoke for the patriciate. He informed the committee that the Chronicle's art critic, Alfred Frankenstein, supported the murals, as did the principal art associations and museums and their boards of directors, "who are among our most highly respected and responsible citizens." When Congressman Will E. Neal asked him, "What percentage of the people who view these paintings today would be inspired in any way whatsoever to become sympathetic to communistic ideas?" Maillard replied, "I should think none at all." Tensions were running high in the hearing room; when Congressman Harry McGregor of Ohio ventured, "I do not think it is art, but I am no artist," Maillard rejoined, "A great many people will agree with you about that."

By the end of the afternoon, a procession of distinguished witnesses had spoken or provided written testimony in favor of the San Francisco paintings. The respected antiquarian bookseller Warren Howell countered charges that Refregier's murals were "historically absurd" by insisting they were not only truthful but based on careful research. Refregier had done his homework. The attorney Chauncey McKeever said that the proper judges should be, "not Legion posts, not marching and chowder clubs, but experts." John Hay Whitney, chairman of the New York Museum of Modern Art's governing board, wrote on behalf of the murals. So did the Artists Equity Association. Congressman Scudder read into the Record a statement revealing the communist sympathies of Equity's founders.

When Hudson Walker of Artists Equity attempted to read a letter from the eminent British scientist and former director of UNESCO Julian Huxley, Congressman McGregor ordered it struck from the Record . McGregor did not like, he said, "to have people from Great Britain putting things in a hearing and making statements like that against a Member of Congress when the person making the statements is not here to answer a few questions that we would like to ask him. Certainly our colleague [Scudder] is a good American and believes in law and order and is a defender of American freedom."(39) In the official Record seven asterisks accordingly replaced Huxley's letter.

Fortunately, Huxley's letter to Refregier was preserved in the National Archives.(40) Huxley commended the artist for a "remarkable work of art and an outstanding example of modern American painting." He and the officials at UNESCO were alarmed, he said, "by the growing tendency in your country to try to exert political control over freedom of thought and expression." The lamentable state of biology and philosophy and the arts in Stalin's USSR "shows what happens when creative thought and expression is subjected to control on political or ideological grounds." Huxley thought it ironic that even as the free world was protesting tyranny in the Iron Curtain countries, "actions like that of Representative Scudder are trying to introduce a similar tyranny into your own great country." It was apparently this last statement that provoked Congressman McGregor to have Huxley's letter deleted, for what made Refregier's art so dangerously "modern" to his critics was precisely its dissent from official mythology.

The directors of all three San Francisco museums entered their protests in turn.(41) Thomas Carr Howe, director of the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, defended the murals and called Scudder's resolution "a shameful measure, in its essence, vandalism." He told the committee that "the three great art museums of San Francisco are solidly against this resolution and the two leading historical societies have not seen fit to support this resolution in any way."(42) Asked by Representative Tom Steed to tell the committee what made him an expert, Howe replied that he had received his doctorate from Harvard. He added that his great-grandfather had arrived in California in 1848, placing him decisively among the state's ancien régime.

Howe's pedigree mattered, for photographs of one mural troubled congressmen sufficiently to engage the director in lengthy cross-examination over a historical detail. The dark neck of a figure about to be lynched by vigilantes strongly suggested to Representative Gordon Scherer of Ohio that the man was a Negro, but since "there were none in California during the vigilante days," added Myron George of Kansas, critics saw in the neck yet another indication of the artist's subversive intentions. When Hubert Scudder noticed that Refregier was not present to clarify the point, his attorney replied that the artist was too busy painting a synagogue to attend. The congressmen were doubly mistaken, for blacks had, in fact, come with the Gold Rush, but the suspicious figure was clearly not one of them.

Grace L. McCann Morley, director of the San Francisco Museum of Art (later the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), sent written testimony ranking Refregier's murals "high among the distinguished American murals of recent years." Though she lacked Howe's pedigree, Morley assured the committee that "as a second generation Californian . . . I find nothing derogatory nor offensive in the subject matter, and there is no evidence of subversive symbolism or reference."(43)

At the hearing's close, attorney Chauncey McKeever inserted into the Record the names of hundreds of citizens who protested the Scudder resolution, among them many of San Francisco's business and professional leaders and philanthropists. Three days after the hearing, the president of the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, J. W Maillard III, cabled his son, Congressman W. S. Maillard, denying Scudder's claim that his organization supported the resolution. His telegram was inserted into the Record.

Five weeks after the congressional hearing, the California Senate voted overwhelmingly to urge Congress to destroy the Rincon murals.(44) The Hearst-owned Examiner recommended their removal if "loyal American citizens" found them subversive.(45) Nevertheless, Scudder's motion never made it out of committee. The murals stayed.

The figures Congressman Scudder saw as "cadaverous and soulless" were, in fact, painted in Refregier's own distinctive style. They may well have been his reaction to the plump pink shepherds in the fake Bouchers and speakeasy murals he and Willem de Kooning had painted for an interior decorator prior to the crash.(46) Congressman George Dondero had already attacked Refregier's lanky figures as examples of "so-called modern art." Representative Myron George of Kansas, like others, was disturbed by Refregier's angular style and said that "in viewing the picture I cannot get over the distortion of the people of that early period, even those of California." Representative Scherer explained, "It is modern art."(47)

The federal art projects never, in fact, encouraged abstraction in public places; Edward Bruce and the Section of Fine Arts advocated a "middle course" in which abstraction had as little place as social protest. Though Refregier's figures and backgrounds were stylized, they were easily recognizable. Far more genuinely modern than Refregier's paintings was Hilaire Hiler's surreal and stylized submarine panorama in San Francisco's Aquatic Park casino, built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA); Hiler's art elicited none of the outrage caused by the Coit Tower and Rincon Annex murals and was even admired by the conservative San Francisco Chronicle and Time magazine.(48) However "modern" in form, the Aquatic Park murals had no modern political content.

Though he had studied with Hans Hofmann, Anton Refregier had little sympathy for nonfigurative art in communal places. To educate a broad public, he had to communicate with it.(49) What he had to say and the place where he said it provoked the unprecedented hearings in Washington.

But if he eschewed a modern style, Refregier also vowed not to paint official subject matter. "We rejected long ago, while on the Federal arts projects," he wrote to the Chronicle's art critic, Alfred Frankenstein, in 1952, "the meaningless type of mural painting where the pioneer dressed in Hollywood fashions, shaven and manicured, would be briskly walking along guided by a 'spirit' of one thing or another, its Grecian garments floating in the wind. This concept pays disrespect to the vitality, power, and labor of those who came before us."(50) Refregier expressed that vitality in two riots, a terrorist bombing, a lynching, several murders, a frame-up, a landgrab, an earthquake, and a world war—not normal fare for a federal post office. In Refregier's gritty, if stylized, realism, Scudder and his colleagues were right to sense danger to received wisdom. In content, rather than in style, Refregier was too "modern."

It is hardly surprising, then, that Scudder first objected to Refregier's depiction of the California Indians as strong and vigorous before the white man's advent. Textbooks and public art had long taught Californians that nature had fated the original inhabitants of their state to vanish before the superior races, and that natives carried little significance except as symbols of brutish humanity from which civilization had risen. Most New Deal art perpetuated the progressive conventions inherited from academic painters such as Arthur Mathews, who in 1914 had painted a mural cycle in the California State Capitol strikingly different from Refregier's.

In Sacramento, Mathews had depicted Indians living in childlike innocence until kindly padres arrived to teach them to work. Allegories of Victory and Civilization then led consecutive waves of immigrants past sidelined Indians toward a city of the future, a new Athens on Pacific shores, where Anglo-Saxon maidens dance in flowery meadows.(51) What Mathews expressed visually, the novelist Gertrude Atherton reiterated in a popular history of the state: "Month after month, year after year, [Father Junipero Serra] traveled over these terrible roads . . . making sure that his idle, thieving, stupid, but affectionate Indians would pass the portals of heaven."(52)]

Refregier was well aware of how and why the Indians had passed heavens portals suddenly, in large numbers, but he censored himself: "Obviously, I could not go into this and get away with it," he wrote. His own cycle begins instead with a California Indian creating art, a sign of intelligence inevitably denied him by the conquerors followed in the next panel by a mother cradling her child.

Preaching and Farming at Mission Dolores. Refregier gave the Native American laborers at the mission a prominence and dignity rare in public art. He was ordered to slim down the friar.

Mural: Anton Refregier, photo by John Horn

That Refregier showed two Indians as strong and dignified workers, standing in the foreground of Mission Dolores with the friar in the background was in itself extraordinary. Though sympathetic to Refregier, Congressman Shelley had trouble understanding what the artist intended. Answering Scudder's charge that the Indians were excessively vigorous, Shelley said that he did not know whether the Indians were strong, muscular, and sinewy but "had always heard that they were very lazy people who were not taken over much by conquest because very little conquest was needed."(53)

Refregier's depiction of California's natives was only the beginning of the remarkable and subtle shift in emphasis he gave San Francisco history. Although his accusers repeatedly charged him with promoting racial hatred, Refregier, throughout his cycle, depicted people of all races working, and occasionally fighting, to build the city. Twenty-six panels formed the prologue to the last, a triptych depicting the catastrophic consequences of racial and national hatreds in the Second World War, Roosevelt's declaration of the Four Freedoms, and men and women of all nations and races sitting together at a round table to guarantee those freedoms.

Perhaps only an outsider could have shown local history with such breadth, depth, and empathy. As Warren Howell and others testified, Refregier knew San Francisco history better than his accusers. He had, furthermore, endowed it with universality. In his complex depiction of "the vitality, power, and labor of those who came before us,"(54) he had painfully pricked the myth of civilizations harmonious forward march. The hearing in Washington had put history, as well as art, on trial, and had shown how inseparable they were in the minds of Refregier's conservative critics.

Shortly after completing the cycle, during the heightened controversy over his murals, the artist noted his fears for what he considered his masterpiece: "Some night, perhaps, men will come with buckets of white paint and it will take very little time to destroy that which took me so long to make. And in the morning it will be just like it was three years ago. White walls without colors, without ideas, ideas that make some people so mad and so afraid."(55)

As it turned out, the passage of time would make vandalism unnecessary.

Despite allegations that the murals promoted class warfare, San Francisco's elite in fact rallied to save them. Certainly, that support was based on principle: to destroy nonconforming art would have been a most un-American activity, one unworthy of San Francisco's claim to be the cultural center of the Far West. But the city's leaders were also too sophisticated to see any real threat to the foundations of American institutions in Refregier's art. Thomas Carr Howe testified that his colleague at the de Young Museum, Dr. Walter Heil, had watched while as many as eight hundred people used the post office. "Not one person," Heil said regretfully, "even looked at the murals."(56)

In 1979 artists and preservationists, led by Refregier's friend Emmy Lou Packard, rallied once more to save his murals when the postal service abandoned its building.(57) Today, the Rincon Annex lobby is a designated city landmark. It serves as the foyer to an upscale mixed-use office complex called Rincon Center. The murals were restored in 1987 by Thomas Portué.

Of the hundreds who pass through it, few pause to look at the paintings that once provoked such heated debate. Fewer still can identify the incendiary events—the waterfront strike, the Mooney trial, or the Sand Lot Riots—and almost no one, except a few aging union members, visits the Longshoremen's Monument across the street where two men were killed in 1934. In Rincon Center's soaring atrium, office workers lunch around a dramatic forty-foot water curtain, below trompe-l'oeil murals created during the Reagan years by the New York artist Richard Haas.[58] Painted to resemble a pastel bas-relief, those murals depict scenes of agricultural abundance, industrial harmony, and financial success. In both style and content, Haas's murals are as much pre- as post-modern. They are exactly what Hubert Scudder said he wanted.

Notes

1. U.S. Congress, Committee on Public Works, Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds, Rincon Annex murals, San Francisco, Hearing, 83rd Congress, first session, May 1, 1953, 1-87.

2. Scudder's accomplishments in the Capitol, detailed in a thin volume entitled Memorial Addresses and Eulogies in the Congress of the United States on the Life and Contributions of Hubert Baxter Scudder (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1968), consist chiefly of water projects for his home district, though his successor, Representative Don Clausen, wrote in his introduction to the volume that Scudder's greatest achievement was "to put Sebastopol on the map."

3. Though Refregier was accused of political radicalism, his figurative and narrative style was fundamentally conservative. While working on murals for the 1939-40 New York World's Fair with Philip Guston and others, Refregier wrote in his diary that the studio was "the closest to the Renaissance of anything, I am sure, that has ever happened before in the States," a paraphrase of Augustus Saint-Gaudens's similar remark about the gathering of artists that produced the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Though the events depicted at Rincon Annex are occasionally provocative, the programmatic narrative remains academic and firmly rooted in Renaissance precedent. Refregier's diary is quoted in Francis V. O'Connor's introduction to Art for the Millions (Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic Society, 1973), 22-23. For other post office projects, see Karal Ann Marling, Wall-to-Wall America: A Cultural History of Post Office Murals in the Great Depression (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1982); and Marlene Park and Gerald E. Markowitz, Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984). For the academic tradition, see Fikret K. Yegül, Gentlemen of Instinct and Breeding: Architecture at the American Academy in Rome, 1894-1940 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991).

4. Dwight Clarke, William Tecumseh Sherman, Gold Rush Banker (San Francisco: California Historical Society, 1969), 305; Victoria Post Ranney, ed., The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. 5, The California Frontier, 1863-1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990); Joshua Speed, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln and Notes of a Visit to California (Louisville, Ky.: John P. Morton and Co., 1884), 65.

5. Joseph Donohue Grant, Redwoods and Reminiscences (San Francisco: Save-the-Redwoods League and Menninger Foundation, 1973), 11.

6. Greg Mitchell, The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair's Race for Governor of California and the Birth of Media Politics (New York: Random House, 1992).

7. Mike Quin [pseud.], The Big Strike (Olema, Calif.: Olema Publishing Co., 1949).

8. The material for such an inventory and appraisal is on index cards and in other primary sources in the National Archives.

9. George Biddle, "Art under Five Years of Federal Patronage," American Scholar 9, no. 3 (Summer 1940): 333.

10. William E McDonald, Federal Relief Administration and the Arts: The Origins and Administrative History of the Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1969), 359. For the academic tradition against which artists like Refregier were reacting, see the catalogue The American Renaissance, 1876-1917 (New York: Brooklyn Museum and Pantheon Books, 1979).

11. Logan's campaign against un-American modernism resembles contemporary attacks against "degenerate" art in Germany. See the editorial "Art Is Sick" from Munich Illustrated Press (e.g., "Only when art returns to a proclamation of beauty and becomes once more a vehicle of sanity and naturalness, will it become possible to speak again of German art"), cited in Josephine Hancock Logan, Sanity in Art (Chicago: A. Kroch, 1937), as well as the illustrations of "good" versus "bad" art in the same volume.

12. Gerald M. Monroe, "The Thirties: Art, Ideology, and the WPA," Art in America 63 , no. 6 (November-December 1975): 67.

13. Biddle, "Art under Five Years of Federal Patronage," 335.

14. The political controversy surrounding the Coit Tower project is related in Masha Zakheim Jewett, Coit Tower, San Francisco: Its History and Art (San Francisco: Volcano Press, 1983).

15. Richard D. McKinzie, The New Deal for Artists (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1973), 25.

16. Joseph Danysh gives a personal account of how the Examiner doctored the photograph, in "The WPA and the Great Coit Tower Controversy," City of San Francisco 10, no. 30 (February 4, 1976): 20-21.

17. Evelyn Seeley, "A Frescoed Tower Clangs Shut amid Gasps," Literary Digest 118, no. 8 (August 25, 1934): 24.

18. Its official name changed to the Treasury Section of Fine Arts in 1938 and later to the Section of Fine Arts of the Public Buildings Administration of the Federal Works Agency. It died along with its director, Edward Bruce, in 1943. See Karal Ann Marling (as in note 3) for an anecdotal history of art controversies that preceded the Rincon Annex hearings.

19. San Francisco Chronicle, November 15, 1942.

20. Anton Refregier's account of his experiences working on the Rincon Annex murals is in a typed, undated [ca. 1949] manuscript in the ACA [American Contemporary Art] Gallery papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, roll D304, frames 1099—1106.

21. Ibid., frame 1105 (p. 7).

22. People's World, March 19, 1948; San Francisco Examiner, November 14, 1947.

23. See San Francisco Examiner, April 16, 1948.

24. Refregier account, frame 1104 (p. 6).

25. Ibid.

26. People's World, March 19, 1948.

27. People's World, March 28, 1948.

28. San Francisco Examiner, October 26, 1948.

29. George E Sherman, "Dick Nixon: Art Commissar," Nation 176, no. 2 (January 10, 1953): 21.

30. Dondero is quoted in Mathew Josephson, "The Vandals Are Here: Art Is Not for Burning," Nation 177, no. 13 (September 26, 1953): 244.

31. "The intellectual-moral achievements of the Roosevelt-Truman era are now to be liquidated; its paintings along with its social plans are to be consigned to the rubbish heap. The 'inquisition' of New Deal artists and their works was begun promptly after the conservatives took over in 1953, with Anton Refregier as first defendant" (ibid., 247).

32. See Logan (as in note 11), and catalogues for the Society of Western Artists in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

33. Official art in California, at least prior to the Second World War, was often promotional; thus it must be understood in terms of what was not depicted. The Edenic image of the state was designed to attract as many desirable immigrants as possible.

34. Charles White's papers are in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

35. People's World, September 2, 1947. Refregier taught classes at the Labor School while working on the Rincon Annex murals.

36. Gustoh's reasoning was equivocal. See Congressional Record (as in note 1), 20.

37. Congressional Record, 29-33.

38. Refregier's assistant, Louise Gilbert, concluded a letter of June 25, 1953, to the San Francisco Chronicle by saying, "The most charitable thing to be said of Rep. Hubert Scudder, who aired the mistaken charges against the murals in Congress, is that he has never seen them."

39. To indicate the international furor caused by the hearings, Mathew Josephson noted that even "the London Times voiced its disgust at this latest atrocity of the American heresy hunters" (Josephson [as in note 30], 247).

40. Letter from Julian Huxley to Anton Refregier, April 18, 1953.

41. The Archives of American Art has the papers of the museum directors Walter Heil and Thomas Cart Howe, as well as the Chronicle art critic Alfred Frankenstein, all of which may contain further information on the Rincon Annex controversy.

42. Congressional Record, 61.

43. Ibid., 64. In response to Representative Scudder's resolution, Dr. Morley organized the Citizen's Committee to Protect the Rincon Annex Murals.

44. San Francisco Examiner, June 11, 1953.

45. Editorial, San Francisco Examiner, May 18, 1953.

46. McKinzie (as in note 15), 176.

47. Congressional Record, 56. Representative Maillard rejoined that "an artist is entitled to a certain amount of license as far as portrayal is concerned" and that "you are not asking the artist to put on the wall a photographic representation."

48. Henry Miller wrote of Hiler's murals: "Though the decor was distinctly Freudian, it was also gay, stimulating, and superlatively healthy." See Stephen A. Haller, "From the Outside In: Art and Architecture in the Bathhouse," California History 64, no. 4 (Fall 1985): 283; and Steven Gelber, "Working to Prosperity: California's New Deal Murals," California History 58, no. 2 (Summer 1979).

49. Representative Will E. Neal felt that "the pictures represent the cartoonist's way of doing things" and were therefore most dangerous to impressionable minds (Congressional Record, 59).

50. San Francisco Chronicle, March 8, 1952.

51. Mathews's little magazine Philopolis contains numerous articles (many written by Mathews himself) that approvingly cite the "natural" subjugation or extermination of the weaker races by the stronger.

52. Gertrude Atherton, California: An Intimate History (New York: Harper, 1914), 30.

53. Congressional Record, 43.

54. Ibid.

55. Refregier (as in note 20), frame 1106.

56. Congressional Record, 69.

57. Emmy Lou Packard's papers are in the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

58. Douglas Frantz, From the Ground Up: The Business of Building in the Age of Money (New York: Holt, 1991). Frantz implies that Haas was unhappy with the final product.