The Dovre Club

Historical Essay

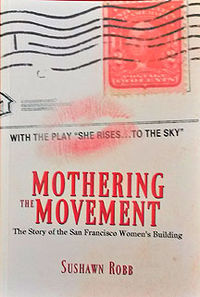

by Sushawn Robb Excerpted with permission from Mothering the Movement, the Story of the San Francisco Women’s Building (Outskirts Press: 2012)

Photo by Jeremy Brooks

The loss of one of the groups viewed as a core tenant [the Full Moon Coffee collective] may have gotten more attention had the timing been a little different. Just as the decision was reached to live with the commission’s restrictions on retail, the issue of one of the current building tenants, the Dovre Club, came to the fore. The Dovre Club was an Irish bar located in the northeast corner of the building. It had its own entrance at the corner of Lapidge and 18th, and the only indoor connection between it and the rest of the building was through the basement.

As the investigation into purchasing Dovre Hall advanced, the word of a pending purchase soon got back to Paddy Nolan, owner of the Dovre Club. A bar had operated in this part of the building since the thirties remodel, developing a clientele that included prominent politicians and influential business men. In 1966, Paddy Nolan bought the liquor license, renamed the bar the Dovre Club and carried on business as an Irish pub. By 1978, when the SFWC first contacted the Sons of Norway about the possible sale of the building, the Dovre Club had accumulated its own venerable legacy. As a supporter of Irish independence and the Irish Republican Army (IRA), Nolan also welcomed pro-IRA activists to use the pub as a meeting ground. Combined with the other politicians and businessmen, the Dovre Club had considerable political clout in a city dominated by machine-style politics. Who you knew was as important, if not more important, than the validity of the issue at stake.

At an August 17, 1978 meeting of the Women’s Building Project, a rumor was reported that Nolan had indicated an interest in selling his liquor license to the Building. Up to this point, there had been no discussion at all about the existence of the bar in the building. The sobriety movement that would sweep the 80’s was in its infancy, but the consensus among the organizers was that no one wanted the building itself to operate a bar. No position was taken on the more general future of the Dovre Club as a continuing tenant, but the general attitude was unlikely to be embracing an Irish pub. If word of the meetings discussion got back to Nolan, as it likely did, it was undoubtedly threatening. The rumor itself may have been planted just to get a reading on what was up with this bunch of radical, feminists, mostly lesbian, planning to turn the building into a women’s community center.

Nolan turned to friend and patron, John Maher, to try to stop the purchase. Maher was from a long-established San Francisco family, a member of the Democratic Party Central Committee, found of Delancey Street and later to be elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Another ally called in for assistance was Jack Davis, a gay man just making his mark as a political consultant/campaign manager.

Maher contacted Women’s Building Project organizers with the claim that Paddy had a verbal agreement giving him first option to buy if the Sons of Norway sold the property. This claim was denied by Al Nelson of the Sons of Norway, but Maher’s threat was to sue and tie the SFWC up in court, effectively holding up the purchase process until it collapsed. The payoff for this extortion was an offer of support and an unspecified “5 figure” donation toward the purchase in exchange for a long term lease for the bar. In addition to the legal attack, Nolan’s supporters also had the clout to exert other attacks that could threaten the viability of the Women’s Building. As the owner of a building, the SFWC took on whole new levels of responsibility (and liability) to meet public codes. With ties to the fire department and other city agencies that enforced laws regarding public buildings, Nolans’ friends could make operating the building difficult and expensive.

In light of the political realities, the organizing committee agreed to sign a ten year lease with Nolan. Twenty years later, when the SFWC was evicting the bar, memories of the actual agreement would vary. Some contend a verbal promise was made that Nolan could stay for his lifetime. Others contend it was promised the Dovre Club could remain as long as the SFWC owned the building. Others believed the collective made a deal to accommodate current political realities with the expectation that someday, the Dovre Club would be gone and the space reclaimed as part of The Women’s Building . In any case,the political and legal challenges to the purchase were dropped. Some donations were collected by the Dovre Club for the Building Fund, but not at the level promised during the lease negotiations. Nor did assuring Nolan that he would be keeping his bar stop their hostility toward the new owners, even after the sale went through.

Shortly after the purchase, a fire was set in the lobby of the building. Damage was minimal (the fire was contained in a trash can) and no suspects were ever charged. Nonetheless, suspicions ran high that an employee of the Dovre Club had set the blaze. There were also a number of bomb threats made, though no bombs were ever found, nor any evidence as to the source of the calls. The idea of a bunch of women owning a building riled more than a few feathers and these threats could have originated with any number of people, operating from a variety of motives.

One incident in the fall of 1979 was very clearly linked to the hostility of the Dovre Club and its patrons. Inside the newly opened Women’s Building, a program was about to be held. The large number of attendees, overwhelmingly female, lined up outside, snaking its way down the sidewalk past the bar.

From inside the bar, a group of men encouraged their female companions to go out and heckle and harass the women standing in line. They did. Epithets flew through the air: “Dykes go home”, “All you need is a man” or “Too ugly to get a man”. Women in line shouted back, exhorting the women to get their own life and break free of male domination. Women’s Building staff tried to defuse the situation, moving the line into the building as quickly as possible and urging those still in line to ignore the bar patrons. This wasn’t the first time such harassment had come from inside the bar, usually targeting women in ones or twos as they came to the building. But the numbers on the street this evening sent tensions to a new high. The SFPD was called, but it was slow to respond.

As the tail end of the line came by, one of the women from the bar drew out a small knife and brandished it at the crowd. Roma Guy was there, and as she urged the woman and her friends to go back into the bar, she felt a blow of a fist to her stomach. Unaware at first that the hand held a knife, Roma stepped back. The woman with the knife realized in horror, exclaiming “I didn’t mean to. I’m Catholic and I really believe!” She dropped the knife and collapsed on the sidewalk. Though Roma had been the one attacked, it was she who ended up reaching out to comfort her attacker. Fortunately, the small blade had barely penetrated Roma’s skin through her coat. Apologies were offered by all the women (including Roma for reasons unclear in retrospect except as a traditional female reaction to conflict.)By the time the police finally arrived, the women from the bar had left for home - without their male companions who’d become suddenly silent inside the bar. The line of women were all inside attending the program they had come for.

No legal charges resulted from this incident, but several days later, Roma paid a visit to Paddy Nolan. She made it clear that this kind of behavior by its employees and patrons was unacceptable, no matter what his political ties were. He agreed, and while quiet grumbling continued for awhile, the open harassment stopped.

Mothering the Movement, the Story of the San Francisco Women’s Building, by Sushawn Robb Published in 2012 by Outskirts Press. For more details, go to here.