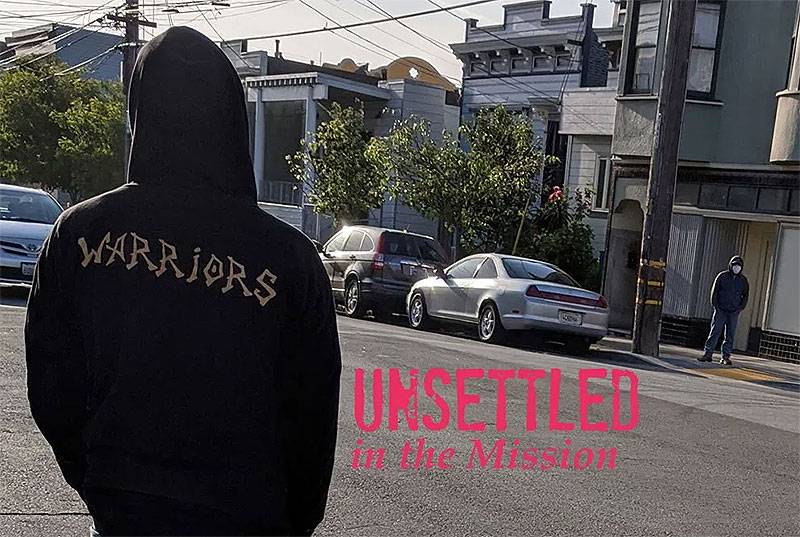

Unsettled: Masked Heroes and Masked Memories of Pandemics in the Mission

Historical Essay

by Adriana Camarena

Originally published in El Tecolote May 7, 2020

As we live with the surprising consequence of the coronavirus pandemic, this article remembers the catastrophic epidemics suffered by the original inhabitants of this place during the Spanish colonial era. Today’s indigenous migrants, often working as day laborers, nannies and restaurant staff, echo those first convert arrivals to the Mission Dolores. The pandemic affects them too, not only in San Francisco but in their original pueblos. A young K’iche’ Mayan day laborer in the Mission tells us how it’s going here and back home.

Profound horror fills the cemeteries

Fifty-one years after the founding of the Alta California missions, Mariano Payeras, a Catalan Franciscan friar and the last President of the California missions wrote to the College of San Fernando in Mexico City about the state of the missions:

“Where we expected a beautiful and flourishing church and some beautiful towns which should be the joy of the sovereign majesties of Heaven and Earth, we find ourselves with missions or rather with a people miserable and sick, with rapid depopulation of the rancherías which with profound horror fills the cemeteries.” (Payeras, Feb. 2, 1820)

Chamis of Chutchui, first Ohlone convert

The Mission Dolores was founded by Franciscan priests a few hundred yards away from the village of Chutchui on the San Francisco peninsula in 1776. There the missionaries attached like a parasite on the native peoples.

The first baptisms at Mission Dolores took place on June 24, 1777. Twenty-year old Chamis of Chutchui was the first neophyte or novice convert. He had lost his father, and his mother lived now in Pruristac (modern-day Pacifica) with her new husband. Seeing as the Spanish priests, backed by Presidio soldier muskets, had no intention of leaving the vicinity of his village, Chamis opted-in, or so I imagine went his thought process. Two other 9-year-old male orphans—Pilmo and Taulvo from Sitlintac (a village close to the Mission Creek Channel and the Giants Ball Park)—were also baptized that day. For the rest of the year, other teenagers and young children, many also orphaned, voluntarily entered the Mission Dolores. By the end of 1777, there were 32 young tribal converts, and so began the folding in of the Yelamu populations of this peninsula into the Mission economy, or what I like to think of as the first juvenile work farm.

Exotic pestilences

With the settlement of the Presidio and Mission of San Francisco, connection to the Bay Area increased by foot, hoof and sail with Europe, Africa and the Americas. With this new worldliness, exotic pestilences both viral and bacterial arrived for which native populations had no immunity, protection or cure.

While there were many ways for an Indian to die at a mission in Alta California, including falling off a horse and being gored by a bull, as far as Mission records from 1769-1850 show, the vast majority of deaths (62%) were due to illness. Observations by travelers and records from the string of 21 missions of Alta California, from San Diego to Solano, show the chronic prevalence of measles, dysentery, typhoid, tuberculosis, typhus, pneumonia, syphilis and gonorrhea. The venereal diseases perhaps were the worst of all. Often forcefully introduced by rapist soldiers and settlers, they led to a slow wasting of adults, rising child deformities, and increased numbers of still births and infertility rates in the native populations.

Among the Alta California missions, the mission of San Francisco de Asís—the Mission Dolores—had the highest death rate and highest infant mortality rate, even in non-epidemic times. Diseases inevitably spread across the Bay into independent Ohlone villages as well.

Getting jumped into the Mission Dolores

Continuous recruitment of Bay natives was required to overcome the die-off of indigenous neophyte laborers at the Mission. By 1794, only seventeen years after the Mission Dolores was founded, the missionaries had emptied out all the Yelamu villages of the central and north San Francisco peninsula. For native peoples living outside the Mission system, their world had rapidly narrowed down as their ecosystems and lifestyles requiring seasonal occupation of lands were destroyed with the introduction of Spanish cattle and mono-crops into the fertile plains they used to hunt and gather on for subsistence; their rivers were also often poisoned by tallow-and-hide processing. Joining the Mission was often a choice to survive.

Recruitment efforts at Mission Dolores next turned towards the populous villages across the Bay. In 1795, entire East Bay Huchiun and Saclan villages were recruited and tule-boat-ferried over to Mission Dolores. It was a time of drought and the row crops at the Mission probably beckoned to the Ohlone as a sole solution to starvation. At the beginning of May that year, the Mission Dolores tribal population reached its highest number yet of 1,095, only to be decimated by a typhus outbreak from which 280 converts fled and many others died.

Once entering the Mission-system, trying to escape was a veritable jailbreak. Any neophyte who ran away was hunted down by Spanish soldiers and forcibly returned to face corporal punishment. A French naval explorer, Jean François Galaup, Comte de la Pérouse, who visited Monterey, Carmel and San Francisco on a scientific expedition in 1786 recorded:

“It must be observed that the moment an Indian is baptized, the effect is the same as if he had pronounced a vow for life. If he escapes to reside with his relations in the independent villages, he is summoned three times to return; if he refuses, the missionaries apply to the governor, who sends soldiers to seize him in the midst of his family and conduct him to the mission, where he is condemned to receive a certain number of lashes with the whip.”

In plain terms, Catholic conversion was just like being jumped into a street gang, blood-in, blood-out; and like street gangs, sometimes you weren’t given a choice.

Petri dish conditions

The missions were a petri-dish of communicable diseases. Historian and SFSU professor Phillip Dreyfus describes the unsanitary conditions at Mission Dolores,

“Whereas natives had lived in lightweight and airy tule-grass structures that they burned periodically when infested with vermin, the mission accommodations were of adobe brick. Dark, damp, overcrowded and unsanitary, these adobe dormitories were breeding grounds for disease. The priests’ practice of protecting female virtue by locking girls and women into these often windowless dungeons at night with a single blanket apiece could not have been conducive to good health. Furthermore, mission population densities that were artificially large compared to those of natives villages aggravated problems of sanitation and water pollution and promoted epidemic conditions. The general effect (as already noted) was an extraordinarily high death rate, especially among women and children. This human tragedy delivered the crowning blow to the ecological revolution the Spaniards had unleashed.”

In 1802, a pest, possibly diphtheria, ran through the northern California missions. But the deadliest outbreak on record at San Francisco began in March or April of 1806. At the end of April, 400 neophytes were sick with measles. By the end of May, 800 were sick and 200 already dead. By the end of the year, the epidemic showed a crude death rate of 405 per thousand population. Every girl under five, three-quarters of all baby boys, and half of all women of reproductive age died in the Mission. The final total of dead were 471 neophytes, with 886 convert survivors.

The greatest tragedy in the wake of the epidemic is that the Mission kept repopulating itself with local indigenous peoples. In 1807, thirty-two Olemaloque and Libantone people from the Point Reyes region arrived to the Mission, and the next year, 142 individuals from the Olemas, Tamals and Omiomis of the Marin Peninsula joined up. Their arrival coincided with the incursion of Alaskan sea otter hunters into Marin, brought there by the United States and Russia.

The Mission Dolores would keep a population of over 1,000 neophytes into 1820, a feat achieved by the incessant recruitment of Bay Ohlone into its death camp. The period of 1800-1820 is generally considered the peak Golden Era of the California Missions due to its highest convert populations and rates of productivity measured in bushels of staple agricultural products.

On December 14, 1817, the Mission San Rafael Arcángel was founded fifteen miles north of San Francisco, simply to tend to Mission Dolores’s sick population. It started with two hundred patients. Perhaps the friars were realizing that they were going to run out of free labor, as the expendable Ohlone populations died off.

A second measles epidemic would strike the missions in 1821, then a third in 1827, an influenza event killed many in 1832, and many more Mission neophytes died in the smallpox epidemic in 1844.

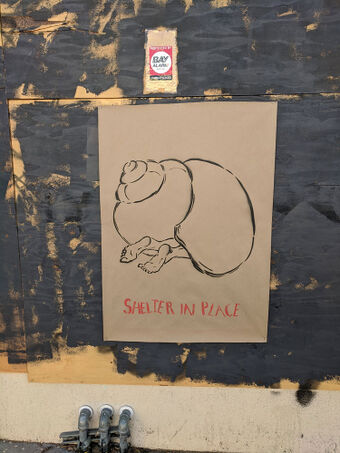

Shelter-in-place

The Coronavirus or Covid-19 outbreak began in San Francisco with its first officially recorded cases on March 5th, 2020. On Monday March 16th, London Breed, the Mayor of San Francisco, jumping ahead of a coordinated action across the five Bay Area counties, issued a shelter-in-place order. The order, one step down from a full emergency lockdown, allowed only essential businesses and travel.

“We know these measures will significantly disrupt people’s day to day lives, but they are absolutely necessary,” said Mayor Breed. “This is going to be a defining moment for our City and we all have a responsibility to do our part to protect our neighbors and slow the spread of this virus by staying at home unless it is absolutely essential to go outside. I want to encourage everyone to remain calm and emphasize that all essential needs will continue to be met. San Francisco has overcome big challenges before and we will do it again, together.”

Poster-graffiti on boarded up shop on Mission Street that criticizes the shelter-in-place order as oblivious to the conditions of homelessness, April 23, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

I listened rapt to the mayor give her address over the public radio waves; a historic moment. The epidemic that originated in Wuhan was a tsunami seen coming from afar that had finally arrived at the shores of San Francisco. I was relieved at the early response.

Fifteen days earlier, I had flown back to San Francisco from a consulting job in Mexico City, already fearful of exposure. I knew I would soon have a paycheck in the bank, and essential activities allowed for health walks. Insofar as my family pod was concerned we could economically, physically and mentally bear the restrictions.

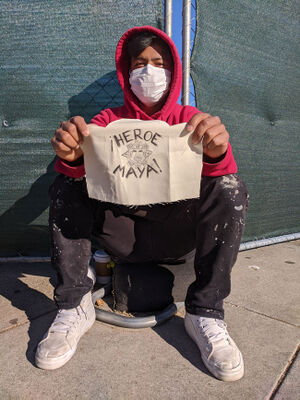

Tecún-Umán shelters in place

Tecún Umán learned of the shelter-in-place order from the Spanish tee-vee broadcasts Monday afternoon of March 16. Tecún and his brother immediately shopped for enough food for a fifteen day quarantine. They live three to a room in a two-bedroom apartment on Capp Street near 24th Street with four other fellow K’iche’ Mayan workers from Sololá, Guatemala.

Young K’iche’ Mayan day laborer waiting for work on Children’s Day at 26th Street and Harrison Street, April 30th, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

The rent for March had been paid, and they had food. Unemployed, but safe, their pod went into lockdown.

Cushy maquiladora

Unemployed, but safe, I started sewing facemasks, obsessively, perfecting my design in each one made, trying to make myself useful from home. After researching other efforts, I settled on giving them away as an incentive to those who donated to Undocfund SF or a similar effort supporting undocumented workers during the Covid-19 lockdown. Mask-making combined with mask delivery walks (and stress-baking) became part of my mental health maintenance plan; the air inflating my shelter-in-place bubble.

A month after the original shelter-in-place order, on April 17th, Mayor Breed made wearing facemasks mandatory: “Any time you’re indoors or within close proximity of others within an essential business or at work … you will be required to wear a mask,” she said. Adding, “It’s just an additional requirement, an additional layer, that is necessary to help us flatten the curve.”

On April 20th, I casually walked to the corner of Cesar Chavez Street and South Van Ness expecting to find a few migrant day laborers who might need masks. I offered my homemade masks by their rope strings, and rapidly back-pedaled as twenty desperate men rushed me to get the few I had.

I cried when I got home. It is one thing to know that undocumented workers will suffer in the pandemic, and another to experience first-hand the desperation of grown men after a month without income. The droplets of my bubble—my scone-baking, mask-making, shelter-in-place bubble—burst in my face.

I was also angry. The migrant day laborers, as expected, were shaking out to be the invisible and expendable population of San Francisco. They were not the target population that would hop online and register for funds through non-profit orgs, and it seemed that they were being completely ignored by the City.

Boots on the ground, migrant day laborers waiting for work on May Day at 26th Street and Treat Street, May 1, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

United in Health

A Facebook post about my corner encounter was met with an immediate offer from artist Stephanie Syjuco—turned community mask-maker on overdrive—to send more masks made by herself and another collaborator Megan Brian. My friend and Mayan Yucatecan warrior, José Góngora Pat, brother of Luis (killed by San Francisco Police officers on April 7, 2016) cut the unsold fundraiser t-shirts from his justice cause so I could make more masks. His cousin María Inés Caamal Ek made a few more for a total of 50 masks to distribute. Annie Danger started decanting gallons of hand sanitizer into 4oz bottles to give away. José would next be free on Tuesday April 26, and it became our target date for delivery out on the day laborer corners.

Our little effort coincided with a novel outreach effort called Unidos en Salud, United in Health that had started a week or two earlier. Flyers were posted about: “The UCSF, the Latino Task Force for Covid-19, and the SF Department of Public Health are partnering to offer free COVID-19 testing in part of the Mission.” The area was the census tract in which I lived. I was eligible, but I had questions. The flyer explained the why of the study stating: “People in the Mission have been heavily affected by COVID-19…” I wrote them requesting more data on the virus in the Mission. Their answer did not resolve my question, but as the study moved forward the City let the cat out of the bag:

Of the 1,216 confirmed COVID cases on April 20th, Latinos represented 25 percent of the positive cases even though we make up 15 percent of the city’s population. Unidos en Salud cited a higher statistics: “~34% of COVID-19 cases (with known race/ethnicity, as of April 18th) are in Latinx population, despite Latinx people comprising only ~15% of SF’s total population.” Honing in on the Mission District, the new information provided by the City showed that our zip code 94110 had the highest number of COVID-19 cases and the City’s 4th highest cases per 10,000 residents. Even more specific, 80 percent of the hospitalized coronavirus patients at San Francisco General Hospital were Latino, where generally, Latinos comprise 30 percent of the hospital population.

In a roundabout way, I came to understand why this tract. Only a broader testing effort would help understand the spread of the disease, and therefore Unidos en Salud chose a Mission census tract that according to the last census was densely populated by Latin people.

I was tested on Saturday April 23rd with my partner at the Cesar Chavez Elementary School. That weekend I also reached out to Jon Jacobo spearheading the Latino Task Force for COVID-19 to volunteer for outreach. Latino Covid-19 task force volunteers had already been making rounds for days in the census tract, and still hadn’t pulled in the numbers they needed. I could only imagine the resistance that my wary Latino working class neighbors had to being tested.

Taking masked precautions, on Monday, with my designated partner, we went door-to-door knocking for three hours in three stairwells of a section 8 building, providing and gathering information.

On Tuesday, I went out with José Góngora Pat, Luis Poot Pat and Annie Danger to hand out masks to day laborers, and spent the rest of the morning into the afternoon with the two Mayan warriors reaching out to the day laborers as part of the Latino Covid-19 outreach effort. We accompanied any convinced day laborers to the testing site to ensure they received expedited registration by the awesome Latinx Spanish-speaking in-take volunteers.

Both section 8 residents and day laborers alike expressed the same fears: Why would they risk infection by going to the testing site? If they tested positive, would they then be whisked away into lockdown or quarantined, unable to make the little income they had left to pay the bills?

My best pitch was always the facts: The Mission Latinxs are disproportionately impacted by the virus, and represent 80 percent of those ill enough to be in a bed or respirator at General. To know if you do or you don’t have the virus, or if you had the virus, will allow you to make better choices about the health and safety of your household. From a bigger picture perspective, their contribution to the study would help everyone understand where or where not there was a focus of infection.

To the day laborers, I would also say, you can be bored standing in line here or over there at the testing site at Garfield Park.

That’s how I met Tecún Uman, as he waited for work on Tuesday morning on 26th Street. I made my best pitch. His group conferred in K’iche’ and suddenly got up and went to get tested.

La Ceiba

True home for twenty-two year old Tecún Umán is the village of La Ceiba, in the municipality of Santa Catarina Ixtahuacan of the Department of Sololá in the highlands of Guatemala on the foothills of a dormant volcano. Social distancing is the greatest sorrow of undocumented immigrants.

Author verified and confirmed that coffee in home pandemic pantry is from Guatemala, Folsom Street near 24th Street, May 1, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

“The family, I miss them, mom, dad, my sister… Mom would get up first to make breakfast. From six in the morning she would go out with the maize to the mill. I would come to breakfast and there she would be palming the masa, pouring water on the corn, making gorditas on the round comal over burning wood.” We both laugh as our mouths water. His mother Catarina would make about 30 tortillas to last for the rest of the day. “I would have a cafecito and a bread, and head off to school.”

His father Martín would head out every day to tend his fields. “My father has a milpa. He grows corn, chiles, beans, lemons for business and for our sustenance… He is of the fields. He knows his life.” Every day with his midday meal, the family would drink fresh lemonade made with lemons from their orchard.

His parents, Catarina and Martin sent him off to school every day, and Tecún only exceptionally missed school at the start of the year, when the whole family, the whole town, would head off to the highlands to pick coffee in January. Tecún’s eyes light up, “I did like to go pick. The company would come around to hire, and gave us a day to leave. We would take a blanket, clothes: it would be cold, it would be hot. My friends, acquaintances went, and there, strangers would become acquaintances. The workday was 6 or 7 hours and for up to two months. We slept on a dirt floor with a blanket. I was 13 or 14 years old when I started going. ” Tecún says it was like going camping with friends, gathering at the end of the day to tell jokes and have fun.

His father was also a sugar cane harvester. “One day he told me, ‘Tomorrow you go with us to see what our work is like.’ And unfortunately I did not go. I went to sleep over with some cousins. The next day, my father asked me: ‘Were you afraid? Do not do that. It is bad.'”

Tecún was afraid of sugar cane harvesting. “Going to work in that trade, the heat is very strong. One is left completely worn out. The canes are tall, their blades like swords. You have to wear a sweatshirt and still they cut. … I would see my father arrive all worn out and sometimes wounded.” The company pays by bushel, not by the hour.

With his parents support, Tecún Umán graduated from high school, but with diploma in hand, he looked about and saw the rising criminality, extortions, and lack of work “even when you had a profession”. He saw his cousins and neighbors getting ahead in building homes and generating wealth for their families, and like K’iche’ Mayans before him, he was drawn to the Mission.

Essential construction workers refurbishing the Garfield Park swimming pool, 25th Street and Treat Avenue, May 1, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Tecún arrived to the City a year and four months ago, pulled into San Francisco by his brother, who was pulled in by a cousin, who was pulled in by friends from villages in the vicinity of La Ceiba. His dream is to save up enough money working construction in San Francisco to build a good house back in La Ceiba, and then, go back home. He had finished paying the debt he took on to make his way to the United States and started saving for his house, when the pandemic hit.

Quarantine in the highlands

Around April 18th a flurry of stories caught my eye: “U.S. Deported Thousands Amid Covid-19 Outbreak” (NYT), “44 migrants on one US deportation flight tested positive for coronavirus” (CNN), “Guatemala says 32 on deportation flight from U.S. infected with coronavirus” (Reuters), and so on.

Tecún tells me a related story. “A man from a neighboring town came here [to the United States] and they seized him and returned him. He arrived in his town as if nothing had happened, but they suspected him of having coronavirus. They had a meeting and they separated him for fifteen days. They made him a house set apart for him to live there during the quarantine.”

I ask if he agreed with those measures. “The truth is yes, for one it is a very contagious epidemic and it can be spread to many, very many. Each town began to close its borders.”

I ask about La Ceiba, and their quarantine measures. “Our president set the rules. Go out to the essentials from 6 in the morning to 4 in the afternoon. Then they changed it to be able to leave from 4 in the morning to 4 in the afternoon so that people could attend to their affairs. And there is a curfew after 4 in the afternoon. After 4 o’clock if anyone is seen on the street, they hand him over to the police and lock him up and fine him. By law, you have to wear a mask in my town. There is a fine for walking without a mask. ”

I ask him if he agrees: “People agree. With the curfew there is no work and if they catch you where are you going to get money to pay the fine? My town is well organized. You have to be cautious. The disease is very difficult.”

Tecún Umán and his apartment pod on Capp Street are also organized. They wear masks. They wash their hands. They keep to themselves. They watch the news.

Part of me wonders if our indigenous brethren hold on to some deep knowledge about fending off disease.

Castigo Maya

I ask what happens to people who refuse to obey. “You see, in my town they have their regulations. For example, sometimes suspects, we call them charros, come into our community to steal chickens for their drink. They created an organization to administer castigo maya (Mayan punishment) to those who steal. If they saw someone rob or hit a woman, things that are very dangerous, they’ll take him out of the house at night and throw corn on the floor. There they’ll have him kneel with a hundredweight of corn on top for an hour.”

Another castigo maya might include getting your arms tied up behind your hands and being raised off your feet by drawing the rope over the soccer goal post. The subject at hand is asked repeatedly whether he has had enough or whether he will continue to carry out misdeeds. The severity of the Mayan punishment increases with the gravity of the harm caused.

The castigo maya stays with me, as I imagine the mask-less techie joggers that whiz by, panting a hair’s breadth away from me on the sidewalk, made to kneel on corn kernels until they cry uncle, promising never again to break basic pandemic etiquette.

Desperate

After keeping a fifteen-day quarantine, Tecún Umán and his K’iche’ posse went back to find work on the streets. They picked up their routine: waking up at 6am, grabbing a coffee and bread, and heading out to the corner to wait. “The corner is the best spot to get a boss.” It was this or they would go hungry. “We are desperate, without funds, without funds we can’t eat, we need to pay rent. We don’t have the rent [for May]…”

Out on the corners, the men are talking through their options. “God only knows how long this disease will last. There are some of our neighbors who think of going back home, but there aren’t even plane tickets. Worst case, we go back, somehow…”

Beyond the disease, they talk about what’s going on in their towns. A version of water cooler gossip, radio hallway, as we say in Spanish. “We talk about what we miss about our towns… We were saying the other day how much we missed going out with friends to find wild oranges and cacao in the hills.”

Over here, of all things Tecún misses most from life in the Mission before Covid-19, he misses playing soccer on the weekends. “I played the Friday night league with team Mayan Sports Club, and Sunday mornings with team La Ceiba.” He’s also never been much of a reader, but the quarantine changes things for everyone. Recently, he found a self-help book that he’s reading online on his phone titled “Positive Mind.” He’s giving it a try.

Gate to Garfield Park soccer field closed due to global Covid-19 pandemic, 25th Street and Treat Avenue, May 1, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

To survive is to resist

The descendants of Coyote, today known as the Ohlone, once occupied the fertile plains of northern California between San Francisco and Monterey and lands farther towards the beginning of dawn, that is, east towards Mount Tuyshtak (Mount Diablo). Though they faced occasional illnesses, their populations had developed a certain herd immunity to local diseases. In case of a severe event, they could retreat from a focus of infection. But under the mission system of indentured toil, their most basic freedoms to health and life were taken away.

Their demographic collapse replicated itself across California. In 1769, it is estimated that there were 300,000 native Californians in the state. Others calculate the population to have been double or greater, but we’ll never know. Researchers also postulate that European diseases arrived in advance of the Spanish settlers, transmitted through established forms of indigenous communication, laying waste to native Californian communities even before Spaniards arrived.

Further settler violence and disease after the Gold Rush continued to destroy California native survivors. From 1845 to 1870, the California Indian population dropped from 150,000 to 30,000, with 60 percent of those lives lost to disease, and the other to murder.

In the bigger picture, varying exotic pestilences had already long ago ravaged the indigenous populations of the Americas. It is estimated that during the first century after European contact in the Americas, 90 percent of the native population of the continent was wiped out by Euro-Asian communicable diseases. Other researchers argue that 95 to 99 percent of the First Nation peoples were wiped out by disease.

I have yet to find recorded Ohlone songs that speak of these terrible diseases, but there are surviving accounts from the Americas. The Annals of the Cakchiquels, a codex of the highlands of Sololá compiled in the 16th century in Spanish by different indigenous writers, records the arrival of unknown pestilence: A plague, possibly smallpox, is recorded to have hit the region in 1518, then again in 1521, and a new epidemic, possibly measles, in 1559. These diseases had walloped northern indigenous kingdoms in Mexico undergoing conquest, and spread into the Mayan kingdoms of Guatemala prior to the arrival of the Spaniards.

“… Great was the stench of the dead. After our fathers and grandfathers succumbed, half of the people fled to the fields. The dogs and vultures devoured the bodies. The mortality was terrible. Your grandfathers died, and with them died the son of the king and his brothers and kinsmen. So it was that we became orphans, oh, my sons! So we became when we were young. All of us were thus. We were born to die!” [Annals of Cakchiquels, Day 12 Camey or April 14, 1521]

The Annals also record the arrival in 1524 of the Spanish conquistadors into the K’iche’ heartlands to wage a final war of conquest for Guatemala against a population already decimated by two bouts of exotic plagues. Six great battles were fought, and in the last stand, a young K’iche’ prince Tecún Umán, today Guatemala’s national hero, fell striking at the commanding invader Pedro Alvarado. One legend says that the prince’s nahual, a shapeshifter Quetzál bird, landed in grief upon his bleeding chest marking the bird forever with a crimson breast. Another says Tecún Umán transformed into a shapeshifter Quetzál himself. The Quetzál remains the symbol of survival of the original peoples of Guatemala who retook control of their lands.

When I asked our masked migrant K’iche’ day laborer if he would like to choose a superhero pseudonym for this story, he didn’t hesitate to say: Tecún Umán.

Author draws a quetzal bird on a mask pattern for a k’iche’ day laborer hero, Pigeon Palace building (a San Francisco Community Land Trust Building), Folsom Street near 24th Street, May 1, 2020.

Photo: Adriana Camarena

Whether it is the surviving descendants of Coyote or the children of Tecún Umán, our indigenous sisters and brothers teach us that in times of great disease to survive is to resist. We must live to fight another day. And that has only ever been possible through great acts of generosity among the everyday working class heroes.

We should also be damned to suffer all the castigos mayas if we allow one more descendant of the original peoples of the Americas to die from an epidemic in the Mission.

About Unsettled

Unsettled in the Mission is a series of literary non-fiction essays by Adriana Camarena to be published periodically as supplements in El Tecolote through January 2019. Her writing is based on portraits of the traditional working class and poor residents of the Mission District for an exploration of Latino identities and histories. This is a collaborative project supported by the Creative Work Fund, however, the views and opinions expressed in “Unsettled” are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Acción Latina.

About the Author

Adriana Camarena is a Mexican from Mexico, complicated by an upbringing in the U.S., Uruguay, and Mexico. She became a resident of the Mission District of San Francisco in 2008. Since arriving in the Mission, Adriana began collecting tales of borders, line-crossings, and overlapping identities told by residents to provide a layered picture of this traditionally working class immigrant neighborhood in California. To learn more about the author and her work, please visit her website.