Transit, Agriculture, and Business Grow in Interwar Years

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Ocean Shore Railroad train taken from Mission Street viaduct looking East, 1915. Islais Creek on right, farms in distance on southern slope of Bernal Heights. (Alemany Boulevard now runs along the route of the tracks and Islais Creek, Interstate 280 is on the left.)

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp32.0166

San Francisco businessmen pushed railroad transportation into the interior and beyond the urban centers during the interwar years. The Ocean Shore Railroad Company connected San Francisco to Santa Cruz, and the Northern Electric Railway served Sacramento valley towns and operated streetcar lines in Chico, Marysville, Yuba City, and Sacramento. Rudolph Spreckels and Benjamin H. Dibblee, both descendants of San Francisco business pioneers and themselves leading figures in the 1920s, sat on the board of directors of the Petaluma and Santa Rosa Railroad. Herbert Fleishhacker served as president of the Central California Traction Company, even after control of the firm shifted in 1928 to the Southern Pacific, the Western Pacific, and the Santa Fe railroads. Originally started in 1905, the company’s interurban electric railway carried passengers and freight from Sacramento to Stockton and owned parts of the Sacramento and Stockton water fronts. San Francisco’s role in valley transportation still included river transport connecting San Francisco, Sacramento, and Stockton. The Yosemite Valley Railroad Company, operating between Merced and Yosemite National Park, was a San Francisco company (William H. Crocker served on the board and John Drum was president in the mid-twenties), and so was the Western Pacific Railroad (organized in 1903 with headquarters in San Francisco). The Western Pacific connected Oakland and San Francisco to Salt Lake City and owned terminals in San Francisco (seventeen acres) and Oakland (one hundred acres, including half a mile on the Oakland inner harbor).(68)

The Southern Pacific Company, despite antitrust challenges, maintained its wide-ranging transportation holdings. Besides its national operations and statewide lines, the Southern Pacific controlled electric interurban railways between San Francisco and San Jose and electric trolley cars in San Jose, Santa Clara, and Fresno. By the mid-thirties, the Southern Pacific’s Electric Railway Company owned over five hundred miles of track centered at Los Angeles and extending into Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, and Orange counties.(69)

What the Southern Pacific represented to railroad transportation, the Pacific Greyhound Corporation meant to bus transportation. From its Pine Street headquarters, it operated a bus service connecting the major cities of the West and Southwest. Branch lines served adjoining territory, and the company’s 302 buses covered approximately 20 million miles each year by the mid-thirties. Another San Francisco company, Yellow and Checker Cab Company (Consolidated) operated 260 cabs in Los Angeles in addition to its 315 San Francisco cabs. The Dumbarton Bridge, constructed specifically for motor vehicle traffic, opened in 1927, providing easier auto and truck connections between San Mateo County and southern Alameda County. Two of William II. Crocker’s long-time associates, George Cameron and Daniel Murphy, served as directors, and officers met in the company’s headquarters in the Crocker Building.(70)

Agricultural development, like transportation, experienced rapid expansion during the interwar years, and San Francisco firms played a central role. Ernest Lilienthal and Mark L. Gerstle organized the Netherlands Farm Company in 1912 to reclaim some 25,000 acres of Yolo County land on the banks of the Sacramento River. Lilienthal had by that time begun his own hop-growing ranches in the Livermore valley, and he sold the crop on the London market through his Pleasanton Hop Company. Other San Franciscans organized similar corporations to reclaim, develop, and farm tens of thousands of acres in nine California counties. The famous ranch lands of Miller and Lux included over 270,000 acres in Merced, Madera, Fresno, Kern, and Kings counties in California, as well as holdings in Nevada and Oregon. San Francisco was headquarters for the firm, and its directors included the president of the Bank of California, Frank B. Anderson, and Marcus C. Sloss and Allen L. Chickering of Chickering, Thomas, and Gregory, a prestigious city law firm.(71)

Frank Anderson, along with Herbert Fleishhacker and other San Francisco financiers, reorganized the Natomas Company of California in 1914, and Anderson became its president. Two of Marcus Sloss’s brothers joined Herbert Fleishhacker and John McKee as officers and members of the board of directors. Besides its 66,000 acres of agricultural land, the Natomas Company operated rock-crushing plants, gold dredgers, and a water company. Both Herbert and Mortimer Fleishhacker sat on the board of California Delta Farms, a San Francisco company with 38,000 acres in the San Joaquin River delta.

Looking south on Davis near Washington. The tall building in distance with the cupola style top is the Matson Building, while the one next to it on the right is the Pacific, Gas and Electric Building. Today this view is blocked by the Embarcadero Center and other highrises.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library

Joseph DiGiorgio, who controlled some forty companies by 1920, organized the massive DiGiorgio Fruit Corporation in that year. With holdings in California, Georgia, Florida, Washington, and Idaho, the company put itself among the world's largest producers and marketing firms by the middle 1930s. From headquarters near the San Francisco Ferry Building, DiGiorgio operated its fruit production empire, as well as its winery in Delano, its lumber and box company in Klamath Falls, and its Baltimore Fruit Exchange. DiGiorgio also owned one-half of the stock in the New York Fruit Auction.(72)

San Franciscans also conducted large-scale Bay Area residential property development through firms such as the Lagunitas Development Company operating in Marin County and the Baywood Park Company’s activities in San Mateo County. The Parr-Richmond Terminal Corporation of San Francisco owned ninety-one acres of waterfront and industrial property in Richmond, participated in a joint venture with the city of Richmond to develop terminal facilities, and operated that city’s wharf and warehouses and its sugar-docking facilities. The Pacific Dock and Terminal Company bought and subdivided over seventy acres along the waterfront in Long Beach during that city’s harbor improvement during the 1920s. San Franciscans also played an active part in the development of tourist and recreational sites during the interwar years, particularly on the Monterey Peninsula, where William H. and William W. Crocker, Herbert Fleishhacker, Kenneth R. Kingsbury, William Humphrey, and Henry Scott created the Del Monte Hotel and Del Monte Forest Lodge.(73)

San Francisco’s role in the oil and hydroelectric industries of the 1920s and 1930s provided the city’s business leaders with another avenue of participation in California’s economic development during the interwar years. San Francisco entrepreneurs Joseph D. Grant and Wallace Alexander played leading roles in the activities of the General Petroleum Corporation, the Honolulu Oil Company, Associated Oil Company, and the Standard Oil Company of California. John Barneson, who was one of the directors of the 1915 exposition, headed the General Petroleum Corporation, organized in 1916 and acquired by Standard Oil of New York in 1928. Joseph Grant, who first met Barneson at a San Francisco club and became a fellow yachtsman at the San Francisco Yacht Club, became first vice-president and a member of the executive committee. He later described the company’s scope of operations:

The corporation held and developed acreage in practically all the principal oil fields of California. An immense refining plant had been established at Vernon, near Los Angeles, and a remarkable pipeline (owned by a subsidiary) extended from the Central Midway district across Tejon Pass and down to that company's refinery and to tidewater—a distance of 184 miles. Another pipeline led from Lebec to Mojave, where the company supplied oil for the fuel requirements of the Santa Fe Railway—a pioneer in the burning of oil in locomotives. . . . At Los Angeles Harbor a terminal was maintained by us which kept busy a fleet of fourteen tankers, with a carrying capacity of 1,000,000 barrels! Ships transported our oil to many countries—to Argentina, to Japan, and to far Cathay. . . . During the expansion of markets, the company entered intensively into the retail sale of its products. Our distributing system covered the Pacific Coast from Alaska to Lower California, nearly 2,000 independent dealers were selling “General” products.(74)

In 1925, the Associated Oil Company owned 42,190 acres in California, Texas, and Alaska, refineries at Avon and in Los Angeles, and pipelines from oil fields to port facilities, plus railway tank cars and sea-going tankers. Associated Oil showed net profits of over $14 million in 1924. Standard Oil of California earned a net profit of over $18 million ten years later during the Depression year of 1934. From his office in the Standard Oil Building at 225 Bush Street, company president Kenneth Kingsbury supervised the corporation’s nearly 500,000 acres of oil-producing land in the United States, as well as over 1 million overseas acres held under contract. Standard’s refineries and pipelines in the Bay Area and in southern California, like its sales and distributing subsidiaries, all took their direction from headquarters in San Francisco.(75)

Joseph Grant later explained how he happened to involve himself in hydroelectric power development in 1911.

Why? I had money to invest. A friend had told me of a dam site on the Upper Klamath River adapted to the production of power on an immense scale. 1 looked at that site. What I saw took my breath away: a vision splendid of tremendous possibilities. Perhaps I had a touch of mountain fever. Anyway, I persuaded some friends of mine to join me; we got control of the power site; we went joyously to work.

The new company, named the California-Oregon Power Company, eventually operated nine generating plants and supplied light and power to forty-four cities and towns in southern Oregon and northern California. Milton Esberg sat on the board of directors along with his neighbor John McKee, who became president of the firm. In 1926 Grant and the board sold “Copco” to the Standard Gas and Electric Company of Chicago.(76)

Grant was also a director, along with Charles Moore, president of the 1915 exposition, of the Coast Counties Gas and Electric Company, which sold electric power and natural gas in Santa Cruz, Santa Clara, Monterey, and San Benito counties. Ferdinand Reis, Jr., head of San Francisco’s Pacific States Savings and Loan Company, also served as president of Midway Gas Company, operating a natural gas pipeline from Kern County gas fields to Los Angeles, and as a director of the Northern California Power Company. Northern California Power supplied electricity to Shasta, Tehama, Glenn, Butte, and Colusa counties, as well as water and natural gas to Redding, Willows, and Red Bluff.(77)

San Francisco bankers Benjamin Dibblee, Mortimer and Herbert Fleishhacker, Frank Anderson, William H. Crocker, and John McKee helped shape hydroelectric power development by their work as directors of California’s most powerful utility corporations: Northwestern Electric Company (founded in 1911), Great Western Power Company (1906), Western Power Corporation (1915), and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (1905). By 1915, Pacific Gas and Electric’s operations served over half the state’s population, in two hundred communities, including eight of the eleven largest cities. During the mid-1920s, Wigginton Creed occupied the presidency, and Wallace Alexander and A. B. C. Dohrmann joined the board of directors. By 1935, Pacific Gas and Electrics territory encompassed 46 counties and 656 cities, including San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, Sacramento, Stockton, San Jose, Fresno, and Bakersfield.(78)

In 1908, C. O. G. Miller (born in San Francisco in 1865) organized the Pacific Lighting Corporation as a holding company to own the stock of the Los Angeles Gas and Electric Corporation. Educated at the University of California, Miller had taken over as treasurer of Pacific Lighting Company in 1886, and he assumed the presidency in 1898. By 1935, with Miller still at the helm, and Wallace Alexander, William W. Crocker, and Milton Esberg on the board of directors, the corporation had made itself the southern California utility giant. Its Los Angeles Gas and Electric Corporation supplied gas and electric power to Los Angeles and sixteen nearby communities. Pacific Lighting Corporation also owned all of the common stock of the Southern Counties Gas Company and over 99 percent of the common stock of the Southern California Gas Company.(79)

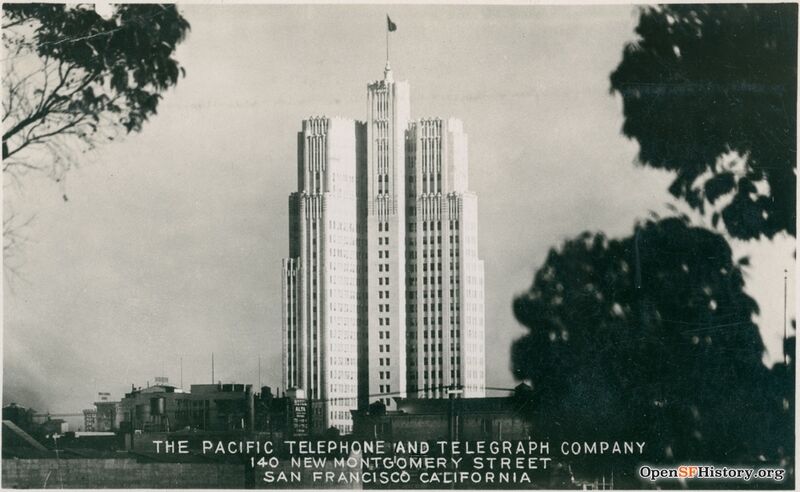

Control over communications throughout the Pacific Coast region likewise gravitated to San Francisco business leaders. By 1915, the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company (1906) had come under the direction of Henry Scott (chairman of the board). William H. Crocker, Walter Martin, and H. D. Pillsbury all served on the board of directors. When Scott stepped down as chairman, Pillsbury took his place, and by 1935 Allen Chickering and Charles K. McIntosh (who had succeeded Frank Anderson as president of the Bank of California) sat on the executive committee. Pacific Telephone’s territory included California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, and northern Idaho, and by 1935 the headquarters staff of this communications empire had moved into the company's new building on New Montgomery Street. A few doors away, the Telephone Investment Corporation conducted its monopoly over telephone service in the Philippine islands.(80)

Pacific Telephone and Telegraph new building at 140 New Montgomery Street, built in the 1920s.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp70.0781

The sugar industry continued to serve as an area for investment by San Francisco business leaders during the interwar years. John A. Buck and his son John A., Jr., and John McKee, as well as William Matson and John L. Koster, involved themselves as officers and directors of the Hutchinson and the Honolulu Plantation companies. Wallace Alexander and Frank Anderson were both directors of the Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar Company and the California and Hawaiian Sugar Refining Companies (its headquarters moved to Honolulu in 1926 after a reorganization). Mortimer Fleishhacker served as one of the two trustees for the Calamba Sugar Estate on Luzon in the Philippines, and Ernest Lilienthal, C. H. Crocker, and B. P. Lilienthal directed the Alameda Sugar Company, which manufactured beet sugar grown in Sutter County. They also had interests in Union Sugar company’s twelve thousand acres of beets and its factory in Santa Barbara county.(81)

By the mid-1920s, California produced nearly 30 percent of the canned goods and preserved foods of the United States. The California Fruit Canners’ Association, organized in 1899, owned and operated thirty factories capable of an output of 5 million cases in 1915. The company changed its name to the California Packing Corporation the following year. By 1935 it had absorbed three other canneries, as well as the venerable Alaska Packers Association. Leonard E. Wood, former governor-general of the Philippines and friend and adviser to Republican presidents, had become president of the firm, and Frank Anderson served as a member of the Finance Committee. Seventy-six plants, including those in the Hawaiian and Philippine islands, thirteen canneries in Alaska, five California ranches, sea-going ships, a shipyard, and a terminal at Alameda all operated under the company’s flag. The firm’s brand names—particularly Del Monte and Sun-Kist—had become household words by the mid-thirties. Hunt Brothers Packing Company (formed in 1896) included Wallace Alexander on its board for a time. The corporation expanded from four to eight canneries during the twenty years between 1915 and 1935, and its operations expanded to include warehouses, cold-storage facilities, and canneries in the state of Washington.(82)

San Francisco also maintained its role in meat packing, viticulture and brewing, flour milling, salt manufacturing, and the supply of cold-storage facilities for perishable commodities. John Hooper’s brother, C. J. Hooper, presided over the Western Meat Company, which by 1925 operated branches in San Francisco, Sacramento, Fresno, Oakland, San Jose, and Stockton. C. O. G. Miller served as first vice-president of the California Wine Association prior to Prohibition, and Mortimer Fleishhacker and H. D. Pillsbury served as directors during the dry years, helping to supervise the company’s liquidation. By the mid-1930s, the Acme Brewing Company had revived its San Francisco brewery and started a Los Angeles plant. Banker Herbert Fleishhacker sat on the board of the Rainier Brewing Company in 1935; the company operated branches in Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle in addition to its San Francisco plant at 1550 Bryant Street. Sperry Flour Company and Albers Brothers Milling Company owned between them twenty- six mills in California, Oregon, and Washington during the mid-1920s. The Golden State Company, successor to a dairy products firm organized in 1905, operated forty manufacturing and distribution plants in California by 1935. The Langendorf United Bakeries (1928) maintained locations in San Francisco, Berkeley, San Jose, Los Angeles, and Seattle by 1935. Leslie-California Salt Company controlled salt lands on San Francisco Bay and in San Bernardino County. The National Ice and Cold Storage Company of California (1912) manufactured ice at forty-three California plants and operated fourteen cold-storage warehouses in eleven California cities.(83)

San Francisco’s lumber companies flourished during the interwar years and expanded to keep pace with the increased demand. The Union Lumber Company (1891) owned 60,000 acres of redwood near Fort Bragg, as well as railroad and shipping facilities to transport its products. Two other firms owned over 68,000 acres in Siskiyou and Del Norte counties, besides the town site of Weed, sawmills, railroad equipment, and steamers. The Pacific Lumber Company (1905) held 42,000 acres of redwood in Humboldt County, two sawmills in Scotia, and an eastern sales agency. Other San Francisco companies owned extensive timber lands in Shasta, Mariposa, and Tuolumne counties in California and Coos, Douglas, and Curry counties in Oregon.(84)

Paper manufacturing comprised an important sector in San Francisco business; leadership in the industry’s expansion during the early twentieth century came from a closely associated group of the city’s leading Jewish businessmen. Louis Bloch had become president of the Crown Willamette Paper Company (1914) by 1925, and both Herbert and Mortimer Fleishhacker served on the board. The company owned plants in Washington, Oregon, and California. Isadore Zellerbach, son of a pioneer paper merchant and president of the Zellerbach Corporation, was a good friend of Herbert Fleishhacker. In 1928, the Zellerbach Corporation and Crown Willamette merged to become the Crown Zellerbach Corporation. Fleishhacker continued as a director, and Bloch became chairman of the board. The company dominated its industry in the West by the mid-thirties, with timber lands in the United States and Canada; paper and pulp mills in California, Oregon, British Columbia, and New York; wholesale divisions in California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, and Utah; and sales offices in fifteen cities throughout the United States. J. D. Zellerbach served as president of the Fibreboard Products Corporation, manufacturer of boxes, cartons, wall board, and other paper products, and J. D. and Isadora Zellerbach also served as officers and directors of the Olympic Forest Products Company, the Grays Harbor Pulp and Paper Company, and the Rainer Pulp and Paper Company.(85)

As California’s population increased after World War I, San Francisco retailers expanded throughout the state. The Owl Drug Company quadrupled the number of its stores between 1915 and 1925 and expanded to California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, and Utah, as well as Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul. A. B. C. Dohrmann and Frederick W. Dohrmann, Jr., expanded the Dohrmann Commercial Company’s (1904) crockery, glass, chinaware, and cutlery business (originally founded as the Nathan-Dohrmann Company in 1886) to Oakland, San Jose, Stockton, Fresno, Sacramento, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Portland. B. F. Schlesinger and Sons operated department stores in Oakland, Portland, and Tacoma, while the Hale Brothers owned five department stores in northern California. I. Magnin and Company's main store served downtown San Francisco shoppers, but the firm also built branches in wealthy areas throughout the state. Sherman, Clay, and Company's (1892) wholesale and retail music and radio stores served northern and southern California, Reno, Portland, Tacoma, Spokane, and Seattle. Foster and Kleiser Company, an outdoor advertising company with headquarters in San Francisco, maintained billboards in 550 cities and towns in California, Oregon, Washington, and Arizona.(86)

As San Francisco business leaders gained experience in conducting operations throughout the Bay Area, California, and the Pacific region, they gradually came to see the city as the headquarters of a regional economy whose wealth required attention to an “international viewpoint.’’ By the early 1930s, worried by the onset of the Great Depression, the officers and directors of firms in San Francisco, Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Mateo counties put aside the rhetoric of competition that had flourished during pre–World War I years and the early twenties. In its place came a concept of metropolitan cooperation that provided a better match to the actual state of affairs and defined San Francisco as the “Hub City” for an integrated economic region. Now, following a decade of discussion and debate about various proposals for metropolitan cooperation (a particularly noteworthy attempt came with Frederick Dohrmann’s Regional Plan Association), business leaders declared “the area to be one economic unit.” The Chambers of Commerce of San Francisco, Oakland, and San Mateo spearheaded a drive “to foster the industrial development of the whole area as a recognized industrial and commercial unity.” San Francisco would occupy a special position:

Characteristic of any regional industrial development is a centering of executive headquarters of manufacturing corporations, banks, and financial houses, transportation companies, and privately operated public utilities in one city in the region. From that city—in our case San Francisco—radiate the wires of central executive management and direction and of financial supply that greatly help to bind the whole area together.(87)

By the beginning of the 1930s, when the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce published reports designed to lure investors away from Los Angeles, Portland, and Seattle, they dramatized the advantages of the Bay Area rather than of San Francisco. San Francisco businessmen themselves led the way toward a decentralized industrial economy in the region. When Joseph Grant and other investors (“for the most part,’’ he said, they were “descendants of California pioneers”) organized the Columbia Steel Corporation in 1908, they chose a Contra Costa County site

because of its strategic position on the deep waters of upper San Francisco Bay, because it is reached by transcontinental railroad lines—and because it was believed that labor conditions there would be less disturbed than in San Francisco.(88)

Caterpillar Tractor Company (1925) operated plants at San Leandro, Stockton, and Peoria, Illinois, and eventually moved its executive offices to Peoria as well. Western Pipe and Steel Company (1910) placed its manufacturing plants in Fresno, Taft, Vernon, South San Francisco, and Phoenix. The Great Western Electro-Chemical Company (Mark Gerstle, vice-president, and Mortimer Fleishhacker, chairman of the board) produced its chemicals at Pittsburg. Atholl McBean, active in the Chamber of Commerce as president and director, was president of Gladding, McBean, and Company (Wallace Alexander and William W. Crocker served on the board). Gladding, McBean, and Company manufactured terra-cotta, brick, tile, and other clay products at eleven California, Oregon, and Washington sites, none of them in San Francisco where its headquarters were located. (McBean served on numerous boards, including Crocker Bank, Standard Oil, Pacific Telephone, and Fireman’s Fund.) General Paint Corporation had half a dozen plants from Tulsa to Seattle, including one in San Francisco. Consolidated Chemical Industries operated plants in Houston, Fort Worth, Baton Rouge, Boston, and Buenos Aires, besides its factory in San Francisco.(89)

By the end of the 1930s, Alameda and Contra Costa counties had outdistanced San Francisco in the value of their manufactured products ($596,749,000 to $313,253,000). Likewise, the value of trade to other San Francisco Bay ports ranked higher than that loaded and unloaded on the San Francisco docks. The tonnage and value of trade in San Francisco Bay ports, however, easily surpassed that of Los Angeles, and the Bay Area could maintain its claim to be the third leading American port after New York and Philadelphia. Measured in dollar terms, San Francisco’s livelihood still depended heavily on its traditional role as a goods handler. In 1939 the city’s manufacturers produced goods valued at $313,253,000, its retailers sold $383,554,000 worth of products, and its service sector took in receipts of $61,893,000. The sales of wholesale firms, however, amounted to $1,377,614,000.(90)

Despite its relative decline as a manufacturing center, San Francisco unquestionably deserved the title “Wall Street of the West,” a term applied by the San Francisco Call and Post in 1926 when it devoted a special section to “The Magic City of Western Finance.” The city’s bank clearings of $7,913,846,281 put it in fifth place in the nation in 1937, following New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco was headquarters of the Twelfth Federal Reserve District, the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange operated on Pine Street, and the city was the insurance center of the West as well. In 1934, San Francisco had seventeen state banks with 171 branches compared with Los Angeles’s sixteen state banks and 56 branches and Oakland’s two state banks and 2 branches. San Francisco’s state banks had 40 percent of California’s total paid-up capital bank stock, 15 percent of bank surplus, and 51 percent of its undivided profits.(91)

San Francisco’s position in the regional economy made it, like Los Angeles to the south and Seattle to the north, vulnerable to the vicissitudes of the Great Depression. However, the Depression did as much to dramatize the power of the San Francisco business elite as it did to demonstrate the shortcomings of the economic order. The several dozen top members of the San Francisco business community met the challenges posed by the Depression with the same combination of civic nationalism and noblesse oblige they had displayed in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake and fire and in the organization of the Panama Pacific International Exposition. United by their friendships and social affiliations, often linked by family ties, and frequently the sons of pioneers, they also prided themselves on their contributions to San Francisco’s economic development and the city’s role in the economic progress of California. When some one thousand demonstrators marched under the banner of the Communist party to the city hall to protest against unemployment in the first week of March 1930, businessman-mayor James Rolph, Jr., upstaged their leaders and turned the protest parade into a rally for future progress. George Hearst, Richard Tobin, Marshall Hale, Alfred Esberg, Harold Zellerbach, and Mortimer Fleishhacker demonstrated their dedication to the future by serving on the advisory board of Mayor Rolph s Citizens’ Committee to Stimulate Employment for San Franciscans.

The directors and officers of the San Francisco Community Chest likewise consisted of the leaders of the city’s business institutions, with William H. Crocker serving as president and Wallace Alexander and Mortimer Fleishhacker as vice-presidents. In the early spring of 1932, with the nation in the grip of the worst depression in American history, a small group of business leaders demonstrated their trust in the city and their conviction that San Francisco would enhance its role as the hub of a thriving Bay Area economy: George T. Cameron, A. P. Giannini, Leland W. Cutler, Herbert Fleishhacker, and two lesser-known associates began their work as the Financial Advisory Committee of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge project.(92)

Notes

68. O’Neill, Ernest Reuben Lilienthal, pp. 109 — 113; Walker's, 1915, pp. 143 — 144, 132-133, 74; Walker's, 1925, pp. 255-256, 170-171, 311, 340-341; Walker's, 1935, pp. 226-227, 224-225, 399-400.

69. Walker's, 1935, p. 361.

70. Walker's, 1925, p. 414; Walker's, 1935, pp. 566-567, 271-272, 984-985.

71. O’Neill, Ernest Reuben Lilienthal, pp. 82 — 87; Walker's, 1915, p. 121; Walker's, 1935, pp. 735-736.

72. Walker's, 1915, pp. 118-119; Walker's, 1925, pp. 496-497; Walker's, 1935, pp 753-754,475-476,557-558.

73. Walker's, 1925, pp. 408 — 409, 507, 467; Walker's, 1935, pp. 306 — 307.

74. Joseph D. Grant. Redwoods and Reminiscences: The World Went Very Well Then (San Francisco. 1973), pp. 108 — 111.

75. Walkers, 1925, pp. 638 — 639. 625 — 627, 655 — 658; Walkers, 1955, pp. 1037— 1038.

76. Grant, Redwoods and Reminiscences, pp. 98 — 101; Walkers, 1915, pp. 61 — 62; Walkers, 1925, pp. 163 — 164.

77. Walkers, 1915, pp. 112-113, 126-127; Walkers, 1925, p. 174.

78. Walkers, 1915, pp. 136, 271 — 272. 159—161; Walkers, 1925, pp. 316 — 318, 216-218; Walkers, 1935, pp. 245-249.

79. Walkers, 1915, pp. 175-176: Walkers, 1925, pp. 234-235; Walkers 1955, 273-274, 277, 284, 288.

80. Walkers, 1915, p. 182; Walkers, 1955, pp. 301, 921.

81. Walkers, 1915, pp. 295-296. 284-286, 289-291; Walker's, 1925, pp. 618-619, 600, 378-379, 605-606, 610-612: Walkers, 1955, pp. 1009-1010. 1000-1001, 993-994.

82. Walkers, 1915, pp. 59-60. 101-102; Walkers, 1925, pp. 381-382, 452-453; Walkers, 1935, pp. 485 — 486, 656 — 657.

83. Walkers, 1915, p. 70: Walkers, 1925, pp. 582, 386; Walkers, 1955, pp. 492, 404, 828; Walkers, 1925, pp. 552—553, 347-348: Walkers, 1955, pp. 622-623, 681- 682, 687-688, 749.

84. Walkers, 1915, pp. 262, 178; Walkers, 1925, pp. 570, 509; Walkers, 1955, p. 940.

85. Harold L. Zellerbach, “Art, Business, and Public Life in San Francisco,” transcript of an interview conducted in 1971-1973 by the Regional Oral History Office, University of California, Berkeley, 1978, pp. 61-62; Coast Banker (San Francisco) 4 (April 1910):209; Walkers, 1915, pp. 81-82; Walkers, 1925, pp. 404, 592; Walkers, 1935, pp. 543-544, 586-587, 770-771, 628, 828.

86. Walkers, 1925, pp. 505, 428; Walkers, 1955, pp. 41 1-4 12, 364-365; Walkers, 1935, pp. 448, 635, 661, 888.

87. Robert Newton Lynch, “San Francisco Looks at Its World,” San Francisco Business, May 14, 1938, p. 18; Capen A. Fleming, “Industrial Growth of the Central City,” ibid., p. 112; Harrison S. Robinson, “The San Francisco Metropolitan Area,” ibid., p. 110. On Frederick W. Dohrmann, Jr., and the Regional Plan Association, see Scott, San Francisco Bay Area, pp. 188 — 201.

88. Grant, Redwoods and Reminiscences, p. 1 16; San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, The San Francisco—Oakland Metropolitan Area: An Industrial Study, 1931, in Chamber of Commerce Records, California Historical Society, San Francisco.

89. Walkers, 1925, pp. 399-400, 387-388: Walker's, 1935, pp. 494, 974, 630-631, 619, 480, 615-616, 526.

90. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce, County Data Book (Washington, D.C., 1947), pp. 48—49; San Francisco Chamber of Commerce Research Department, San Francisco Economic Survey, 1938 (San Francisco, 1938), p. 15.

91. San Francisco Call and Post, Dec. 31, 1926; San Francisco Chamber of Commerce Research Department, San Francisco Economic Survey, 1938 (San Francisco, 1938), p. 20; State of California, Superintendent of Banks, Annual Report (Sacramento, 1934), abstract of report (40 percent common stock, 62 percent preferred stock).

92. Chronicle, March 7, 1930; letter from D. V. Nicholson to A. P. Giannini, May 25, 1932, Bank of America Archives, San Francisco.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 2 “Business and Economic Development”