The Wickedest Man in San Francisco: Ambrose Bierce

Historical Essay

by Dr. Weirde

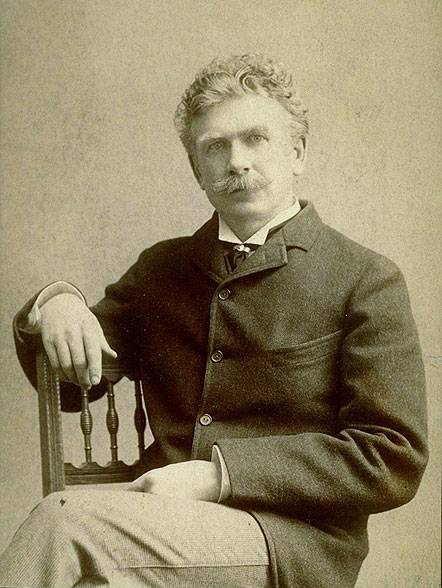

Ambrose Bierce

Photo: courtesy Stephen Mexal

“Air: A nutritious substance supplied by a bountiful Providence for the fattening of the poor.” —The Devil's Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce.

Ambrose Bierce, the world-class cynic best known as the author of The Devil's Dictionary, lived here, in the old Russ Hotel, when he was beginning to scandalize San Francisco with his incisive, vicious commentary.

Bierce launched his career when he took over J.W. Watkins's “Town Crier” column for the San Francisco News Letter in 1868. “Anyone who reads even these early offerings can't help but notice that the improvements under Bierce's editorship were beyond technique -- there was an unmistakable streak of genuine hostility running through every line.”1 Bierce's unique talent for obloquy quickly won him a reputation as “the wickedest man in San Francisco.” At a time when most godfearing white Americans loathed the “heathen Chinese,” Bierce wrote:

“On last Sunday afternoon a Chinaman passing guilelessly along Dupont Street was assailed with a tempest of bricks and stones from the steps of the First Congregational Church. At the completion of this devotional exercise the Sunday-scholars retired within the hallowed portals of the sanctuary, to hear about Christ Jesus, and Him crucified.”

When the good Christians of San Francisco condemned him for this blasphemy, Bierce replied with a mock conversion:

“Lord . . . we beseech Thee to turn Thy attention this way and behold a set of the most abandoned scalawags Thou has ever had the pleasure of setting eyes on. . . . But in consideration of the fact that Thou sentest Thy only-begotten Son among us, and afforded us the felicity of murdering him, we would respectfully suggest the propriety of taking into heaven of such of us as pay our church dues, and giving us an eternity of exalted laziness and absolutely inconceivable fun. We ask this in the name of Thy Son whom we strung up as above stated. Amen.”

Bierce interspersed his ferocious satirical sallies with bizarre, morbid descriptions of accidents, suicides, homicides, and all manner of death and disaster: “The Italians continue their cheerful national recreation of stabbing one another. On Monday evening one was found badly gashed in the stomach, going about his business with his entrails thrown over his arm.” He described missionaries as “men who would beat a dog with a crucifix,” and wrote that a fellow journalist was “suffering from an unhealed wound . . . his mouth.” Though “Bitter Bierce” regularly savaged women, along with the City's ethnic groups, politicians, and churchgoers, he could not be accused of prejudice; Bierce hated everybody. “In his view all of mankind was a hopelessly botched experiment devised in hell, and the stupidity of every soul on earth had nothing whatsoever to do with ancestry.”2

In the 1880's and 1890's, Bierce almost singlehandedly battled the corrupt railroad monopolists who ruled their ill-gotten empire from atop Nob Hill. He called railroad magnate Leland Stanford “Stealand Landford,” insisted that the railroad barons were “public enemies and indictable criminals,” and warned the public that the trains were so often behind schedule that passengers would be “exposed to the perils of senility” before reaching their destinations. Bierce campaigned indefatigably for public ownership of the railroads.

Bierce was also a foe of nascent U.S. imperialism, which was setting out on a course that would lead to thrilling genocidal adventures in Vietnam, Indonesia, and Central America. Though his editor, William Randolph Hearst, almost singlehandedly whipped the nation into the colonialist fury it's been in ever since, Bierce took a jaundiced view of the White Man's Burden:

“We can conquer these people without half trying, for we belong to a race of gluttons and drunkards to whom dominion is given over the abstemious. We can thrash them consummately and every day of the week, but we cannot understand them; and is it not a great golden truth, shining like a star, that one does not understand [what] one knows to be bad?”3

In later years Bierce's behavior grew curiouser and curiouser. He would write from midnight to dawn with a human skull on his desk and a tame lizard on his shoulder, surrounded by a menagerie of frogs, snakes, squirrels, and birds. Along with his caustic journalism, Bierce produced a body of horror fiction that ranks with that of Poe and Lovecraft; his subject-matter was “a truly bizarre three-ring circus of ghosts and murders, animated machines and mad dogs, apparitions and extrasensory perceptions.”4

In 1913, disgusted with the viciousness, greed and chicanery that passes for human life, Bierce disappeared into Revolution-torn Mexico with the avowed intention of joining the insurrection led by Pancho Villa. He explained: “The fighting in Mexico interests me. I want to go down there and see if the Mexicans can shoot straight.” Apparently they could. He was never heard from again; the manner of his death is still a mystery.5

photo: City Lights Books, San Francisco, CA

Notes:

1. Saunders, Richard. Ambrose Bierce: The Making of a Misanthrope. SF: Chronicle Books, 1985.

2. Saunders, p.27

3. Quoted in Saunders, p.76

4. Saunders, p.68.

5. See Carlos Fuentes's excellent book The Old Gringo; if like most Americans you have forgotten how to read, you may experience a vastly inferior simulacrum by renting the movie of the same title at your favorite video store.