The Sutro Baths (ruins)

Historical Essay

by Annalee Newitz, excerpted from In Search of Adolph Sutro in the "San Francisco Bay Guardian", January 13, 1999.

Sutro Bath ruins, Jan. 12, 2013.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Sutro Bath ruins at sunset, Jan. 12, 2013.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

Sutro Baths and environs from the air, 1935.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp37.02248

| Built in 1896 by former mayor and eccentric mining tycoon Adolph Sutro, the Sutro Baths were a wonder of their time. The biggest indoor natatorium of its kind, the Baths used sea water from adjacent Ocean Beach to fill six saltwater pools, and featured one freshwater pool, hundreds of dressing rooms, slides, springboards, a large amphitheater, and later an ice rink. Sutro died while the Baths were successful, and the attraction continued in popularity until it fell into disuse during the hard economic times of the 1920s and 30s. Planned development along the oceanfront property and multiple fires meant the Baths’ demise in 1966. The Baths remain a centerpiece of the west side of the city’s history and its ruins are still explored by locals and tourists alike today. |

Following a steep dirt road down to the place that a faded sign refers to as Sutro's Baths, I became smitten by the idea of someone building a bath house so vast in what was at that time a relatively deserted part of the City. I couldn't wrap my mind around what the thing would have looked like. On a second visit, I brought my archaeologist friend Alison Boles along, and she immediately began sifting through the rubble, looking for layers. The more we found, the more information we wanted about what we saw: an intriguingly huge stone pool; a smaller oval pool; a decaying grand stairway of cement; twisted and rusted metal hooks all along the edges of the pool; an odd square room divided up into small cells; a tunnel blasted through the rocks which fills with water during high tide; and dozens of incomprehensible remains of wooden doors, water traps, and pipes that looked like something out of Terry Gilliam's industrial nightmare film Brazil.

Sutro's Baths, as Alison and I discovered over several months of sporadic research, were in fact Adolph Sutro's idea of a solution to the industrial nightmare of late nineteenth century working life, corporate greed, and economic depression. But the history of his Baths is, ironically, the history of how San Francisco came to forget about one of its greatest benefactors and Progressives, a wealthy property owner whose successful mayoral campaign in 1894 nevertheless boasted the anti-big business slogan, "The Octopus Must Be Destroyed!" The Octopus as readers of turn-of-the-century San Francisco rabble-rouser and novelist Frank Norris already know, was populist shorthand for huge, monopolistic corporations like the Southern Pacific Railway (owned, in part, by magnates Leland Stanford and Mark Hopkins). One of Sutro's lifelong projects was defeating the monopoly that the Octopus-like Southern Pacific Railway held over U.S. railroad systems and the trains in San Francisco itself.

While the Octopus squeezed local businesses and raised fares, Sutro imagined that his Baths would do the opposite by providing the masses with healthy, safe, low-cost entertainment. Having already turned his home at Sutro Heights into a free public park, he believed that his Baths would continue a tradition of what he called in his will the public resort or park. When Sutro discovered that Southern Pacific wouldn't give SF train riders transfers—forcing them to pay two five-cent fares to cross the City and get to Sutro Heights—he built his own railway lines and public transportation and charged the flat five cent rate. Because a typical clerk in the 1890s made roughly twelve dollars a week, twenty cents just for a round-trip train ride was in fact rather pricey.

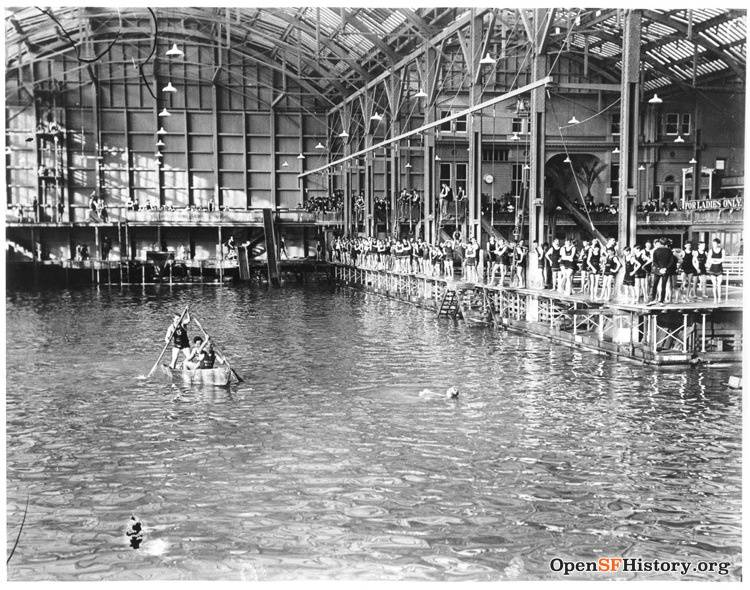

Like his Baths, however, Sutro's Railroads on Greenwich and Clement Streets are now long gone. These days, its hard to imagine someone spending their own money to build cheap transportation and entertainment for the masses. And there's no denying that the scope and complexity of the Baths were geared to masses. When they opened in April 1896, the three-acre Baths housed three restaurants; a museum; five large, salt-water bathing pools of varying temperatures which were filled and drained by the tides coming in through a tunnel hollowed out of the adjoining rocks (visitors today can walk inside this tunnel); a huge outdoor tidepool (the u-shaped contour of which you can still see, full of seawater and plants); bleachers to seat several thousand; a house band; and attractions such as the haunted swing and the panorama of the world.

Sutro Baths c. 1910, looking north over the main pool.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp4.0316

Up to 25,000 bathers could fit into the Baths on a given day, and more than 1600 could be accommodated in the 517 private dressing rooms (conveniently, there were 40,000 towels available for rent). The entire establishment was constructed inside an enormous three-peaked glass enclosure. According to visitors' reports, a great deal of the structure was made from stained glass, and the baths below were frequently dappled with rainbow colors from the sun shining down through the roof. Sutro placed dozens of display cases full of his memorabilia from trips around the world--including, weirdly enough, a mummy--all throughout the halls to make his attraction educational too. The place almost sounds like a direct ancestor of the sumptuous discos and raves for which San Francisco is still famous.

Sutro Baths vestibule.

Photo: C.R. collection

Although the Baths were wildly popular for the last months of Adolph Sutro's life in 1898, they fell into disuse during the twenties and Depression-plagued thirties. Landscape architect Elliott Insley writes that by 1937, income from the Baths was so minimal that Sutro's grandson converted the largest swim tank into an ice rink; a later owner removed all the swim tanks to make way for one giant ice rink and museum. Then, inevitably, the historic structure was threatened by condos. Robert Fraser bought the decayed ice rink in 1964 and planned to raze it so he could build some seaside properties. The last remnants of the Baths were finally destroyed by arson as Fraser was demolishing them in 1966 (hence the melted look of some of the steel and glass fragments you can find near the tanks). Luckily, the condos never materialized, and the National Park Service bought the beach and Bath ruins in 1980. Although the Baths today are dotted with a few danger signs, nothing has been done to change them since that time. What remains are some large tanks, a battered chunk of the pump house (this is the square structure divided into several small cells), the tunnel mechanism which allowed the tides to fill and empty the swimming pools, and outlines of the bleachers and grand entrance stair. People are allowed to climb all over the crumbling stones unhindered, which has unfortunately led to some vandalism.

Looking north from the Cliff House with the Sky Tram passing the back (west side) of Sutro, c. 1955.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp25.1226

January 12, 2013.

Photos: Chris Carlsson

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/Ff5A0vVKJgc" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Josiah Clark shot this footage of a river otter hanging out at the edge of the Sutro Bath ruins in 2014.