The First Five Years of Muni through Maps

Historical Essay

by Eva Knowles, 2023

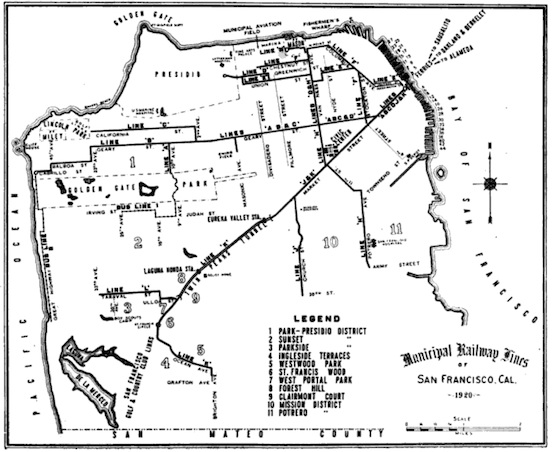

Figure 1: “Municipal Railway Lines of San Francisco, Cal.” In The Municipal Railway of San Francisco, 1912-1921, by San Francisco (Calif.) Bureau of Engineering and M. M. O’Shaughnessy.

| Launched in 1912, Muni emerged as a key player in San Francisco’s recovery from the 1906 earthquake and its efforts to reestablish itself as a major urban center. This study uses period street maps to reveal how Muni’s development was not just a response to local transportation needs but also a strategic element in the city’s broader political and economic ambitions. |

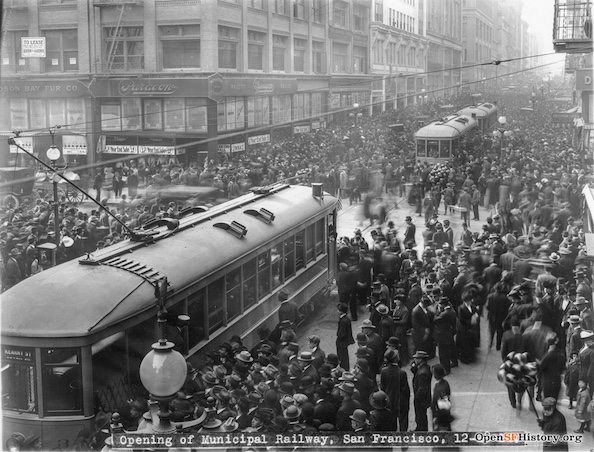

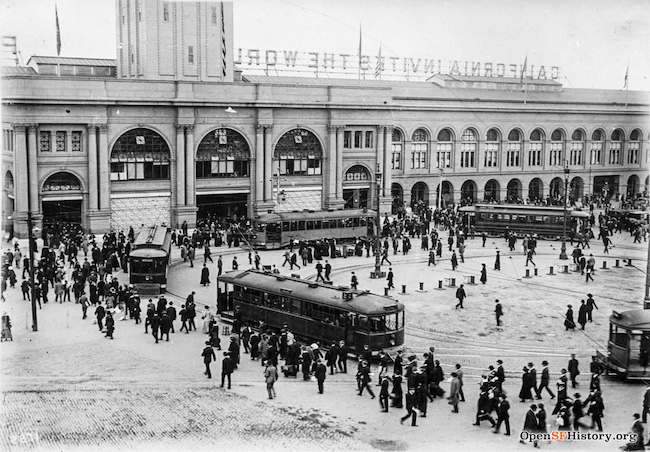

A crowd surrounds Cars #1, #2, and #3 at the opening of the Municipal Railway in 1912.

Photo: OpenSF History / wnp27.6377

At noon on December 28, 1912, a cheering crowd of fifty thousand congregated on the corner of San Francisco’s Geary and Market Streets, bringing traffic to a halt. As the San Francisco Municipal Railway’s first ten streetcars made their way down Geary, the cheering only intensified, accompanied by music and firecrackers (1).

Muni was born in a time of great change for San Francisco: it had been just six years since the earthquake and subsequent fire that had devastated the city, previously the richest and most prominent Pacific port as well as the cultural and financial capital of California. The 1910s can be described in many ways, but two stand out most prominently in the context of Muni. First, the 1910s were characterized by staunch efforts to restore San Francisco’s image of prosperity and return it to its former glory on the world’s stage. The 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), a world’s fair celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal, would be the culmination of these efforts, bringing in tourism dollars and showing off the city’s recovery. Secondly, this time was characterized by heated debates over public transportation and ownership of utilities; as the Progressive reform movement swept across the city, residents would call into question the effective monopoly on street railways. Muni would be the country’s first publicly-owned transit system in a major city, followed shortly thereafter by municipal systems springing up across the country.

These two stories have long been treated as occurring in parallel—separate, rather than entangled. While scholars of the PPIE have examined the reconstruction of San Francisco’s post-disaster image, scholars of Muni have approached its early history through two main lenses: that of its spatial function as the city developed outward from its downtown core, and that of its representing San Franciscans’ Progressive impulse toward public ownership. A closer look at street maps from the period reveals that these stories are deeply enmeshed in one another. Muni’s political significance in its first five years was layered: in addition to its being “the People’s Railway,” as it is so often called, Muni was crucial to maintaining San Francisco’s national and international status for its role in tourism and the World’s Fair.

Muni in History

Conventional histories have portrayed Muni in its first five years as aiming either to provide new access to neighborhoods or to compete, both economically and ideologically, with private enterprise. Approaching Muni through a strictly pragmatic conception of public transportation as offering people greater mobility across urban geographies, some scholars have argued that Muni’s primary function was addressing the city’s spatial needs. A report published by the San Francisco Transportation Technical Committee titled History of Public Transit in San Francisco 1850-1948 claims that Muni’s expansion was mostly aimed at development, rather than competition with private enterprise. According to author Roy S. Cameron, Muni’s creation was seen as vital to opening southern and western areas to prospective home-seekers. It was estimated at the time that one-third of the city remained unpopulated due to a lack of public services including both water and street railways; because of this, potential residents were settling elsewhere in the Bay Area (2). The United Railroads was essentially barred from expanding service by charter amendments of the last decade, leaving this responsibility wholly in the city’s hands.

Other scholars have argued that Muni in its early years more so served as a symbol of San Franciscans’ stake in the Progressive reform movement. In a journal article entitled “James Rolph, Jr., and the Early Days of the San Francisco Municipal Railway”, Morley Segal argues that the birth of Muni was ideologically motivated, representative of passionate public interest in the municipal ownership movement (3). By the first decade of the twentieth century, private ownership had come to represent corruption and mistreatment of labor, evidenced by the bloody streetcar strike of 1907 and the 1908 graft prosecution involving Patrick Calhoun, president of United Railroads. The construction of a municipal railway “signified more than a matter of routine municipal business”: it was about satisfying the people’s feelings of both intense dissatisfaction with United Railroads and personal ownership of their city (4). The issue ultimately became crucial to local politics as politicians including Mayor James Rolph learned that they could garner favor by showing support for the railway.

Joanna Dyl offers an extension of this idea in Seismic City, arguing that the streetcar served as a daily “point of contact” between corporations and patrons, and was therefore a central battleground for questions about labor and ownership (5). Street railways had long been seen as a symbol of corporate reach and capitalist over-industrialization, yet city residents were deeply dependent on them as they commuted back and forth from downtown. Situating this argument in a broader exploration of the city’s earthquake recovery, Dyl claims that the more dependent on the railways residents were—such as in 1906, when destruction dislocated sixty-six thousand people from their central neighborhoods to more distant ones—the more San Francisco residents wanted to control it (6). In fact, the earthquake was seen by both labor unions and private corporations as opening up an opportunity. There was great power to be claimed in the construction of a new city: by harnessing infrastructure now, the people could ensure they had a say in San Francisco’s future.

Maps: A New Perspective

An examination of street maps from 1910s San Francisco shows that the story of the Municipal Railway was also intermeshed with San Francisco’s post-earthquake image-making. These maps call into question the argument that Muni in its first five years largely functioned to fulfill spatial needs, and while it stands that Muni was symbolic of the people’s desired ownership of their city, Muni also took on a political significance on the national and international levels in this era when San Francisco’s status was on the line. Through its centrality to tourism and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, Muni functioned as a tool for maintaining San Francisco’s imperial legacy.

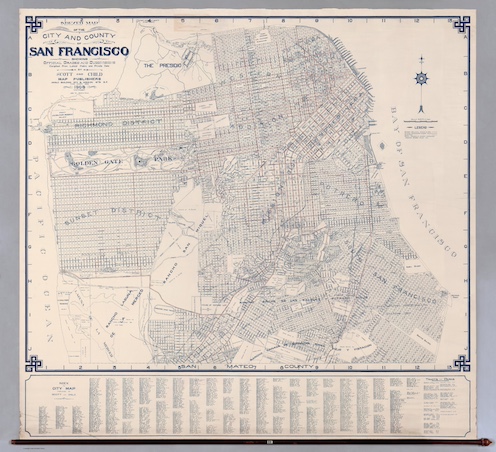

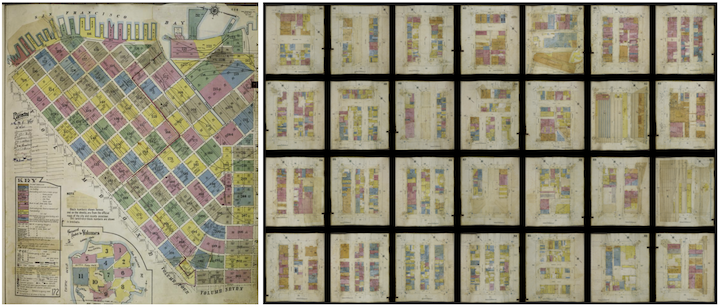

Figure 2: Scott and Child. Indexed Map of the City and County of San Francisco Showing Official Grades and Subdivisions.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

Even the most surface-level analysis of maps is helpful in challenging scholars’ claims about spatial representation and Muni’s broadening access to outlying neighborhoods. Both before and after the opening of the Municipal Railway, large areas of San Francisco remained inaccessible by streetcar. Figure 2 provides a baseline for comparison. This map, published in 1908, predates Muni; it can therefore be assumed that the streetcar routes depicted on the map belong to the United Railroads of San Francisco (URR), which by 1902 had acquired the city’s railway companies. It shows, then, where lines already existed before Muni and where there were transportation needs with regard to space. First, we can notice a dense arrangement of lines through San Francisco’s “50 Vara District” (today’s Downtown) and “100 Vara District” (today’s SoMa), and the “Western Addition” (which includes today’s lower Pacific Heights, Panhandle, Hayes Valley, and Haight Ashbury). On the other hand, various neighborhoods appear underserved, such as the Sunset District and parts of the Marina, Potrero Hill, and Richmond districts.

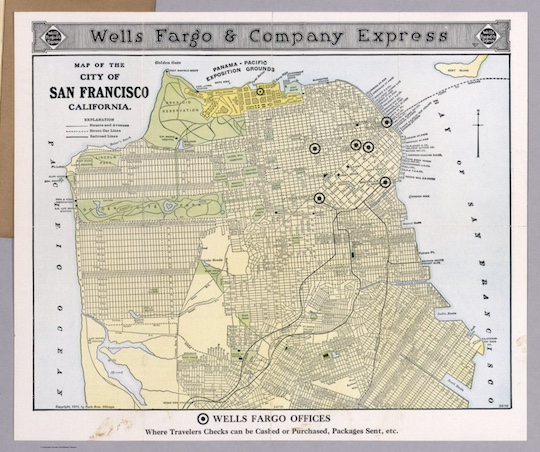

Figure 3: Sanborn Map Company, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from San Francisco, San Francisco County, California. Vol. 10, 1915.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

Figure 4: Sanborn Map Company, Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from San Francisco, San Francisco County, California. Vol. 2, 1913.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

Later street maps reveal that this spatial dynamic—of northern and eastern regions being overserved and southern and western regions being underserved—did not change in the early days of Muni. Figure 1, a map created after Muni’s inception in 1920, shows its lines in isolation, excluding streetcar lines by other corporations such as the URR altogether. It also only includes street names when they correspond to a turn in the route, and thus seems to be trying to convey in a visual, not so highly technical manner, Muni’s reach. Yet what it really shows is how that reach just isn’t that broad. Upon comparison with Figure 2, this becomes all the more clear. The earliest lines, which one would logically assume are the highest priority for construction, largely do not extend into underserved areas, but instead mostly overlap with or run only a few blocks away from existing URR lines. The only area where real expansions of access was made in Muni’s first five years is the Marina District, where temporary lines served the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps from the period (Figures 3 and 4) tell a similar story; housing remained far sparser in outlying neighborhoods than in inner ones, corroborating the idea that transportation had a significant impact on population sprawl.

Streetcars, Tourism, and the PPIE

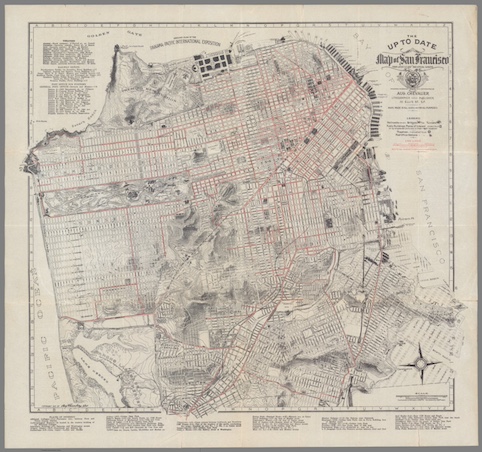

Figure 5: Wells Fargo & Company. Map of the City of San Francisco California.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

Figure 6: Chevalier, August. The Up to Date Map of San Francisco.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

Dipping below this surface-level analysis provides a picture of Muni’s non-spatial, less traditional functions. First, the distinct red or dashed lines that appear on many maps of the period, denoting the paths of streetcars, cannot be taken for granted as a natural element of a street map—that is to say, they are not an element that helps show what the city physically looks like. The commonness of their inclusion points to a particular attitude: what are the streets, if not the railways that run along them? Maps produced for tourists at this time treated streetcars as a crucial part of the streets themselves, and of the city. For example, Wells Fargo & Company published to tourists in 1915 a map that highlighted, in addition to their own offices, the streetcar lines (Figure 5); so did lithographer August Chevalier in the same year (Figure 6).

In fact, streetcars were central to San Francisco’s tourism philosophy as it had crystallized in the 1890s and 1900s. The nature of tourism was changing, now privileging visual consumption (7). Local tourism promoters hoped to attract tourists of diverse budgets and class backgrounds, which meant that they needed to provide visitors with the ability to visit and view the city’s attractions at little expense. While upper-class tourists would, hopefully, patronize these attractions, most important was the opportunity to promote an image of the city as a whole: its successes, its cosmopolitanism, and the diversity of sights it offered. Streetcars were crucial to this aim for their efficiency, affordability, and comfort (8). Promoters began to publish self-guided sightseeing tour itineraries where one could see the entire city via streetcar; the United Railroads also formulated their own comprehensive tour. Ultimately, it would be the streetcars that painted for the city’s tourists an image of its progress and prosperity.

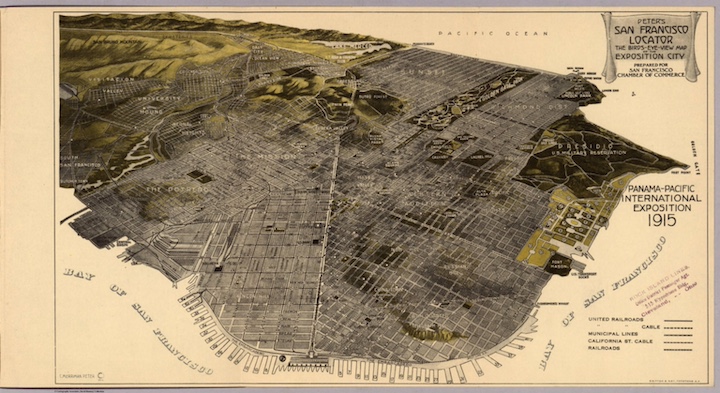

Figure 7: San Francisco Chamber of Commerce, and C. Merriman Peter. Peter’s San Francisco Locator: The Bird’s-Eye-View Map of the Exposition City. 1915.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

The PPIE has been considered the culmination of San Francisco’s early twentieth century project with regard to tourism; it makes sense, then, that the streetcar played an integral role in that as well. Many maps that claimed to represent an “Exposition City” or the Exposition itself in fact heavily emphasized public transportation. This was not only done through the red and dashed lines representing streetcar lines, but also through maps’ very perspectives. Perhaps the best example of this is a map made for the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce which features a bird’s-eye-view or panoramic perspective, meaning that the city is represented as if viewed from above and at an angle (Figure 7). A particular feature of birds-eye-view maps is that some regions of the city will be shown as closer, in greater detail, and others as further away. Though “Map of the Exposition City” is literally in its title, the map does not center itself around the Exposition site. Instead, it centers on Market Street, placing the Exposition all the way on the right side of the map. Its dashed streetcar lines are made especially noticeable by the up-close view of Market Street, a central corridor for street railways, and the city’s overserved downtown.

Figure 8: Tourist Association of Central California. Central California : Pleasure Land for the Tourist : Exposition Map. 1915.

Source: David Rumsey Map Center

A map of the Exposition grounds by the Tourist Association of Central California treats streetcar lines similarly (Figure 8). The solid black streetcar lines are of a similar weight to the lines outlining the fair’s key buildings; this implies an equation of importance between the two features. Further, the borders of the map have been drawn seemingly in alignment with the railways, extending just far enough past the edges of the Exposition Grounds to show all nearby lines: it extends three blocks south to a streetcar line at Greenwich and Lyon, and one block east to a railway loop on Van Ness. To these mapmakers, the street railways were a crucial element of the “Exposition City”—one that should not just be included, but to which the map must be oriented.

Furthermore, as mentioned, a comparison of street maps from the period reveals that Muni’s only major expansion in its first five years was the construction of temporary lines to serve the Exposition. Newly constructed and newly acquired lines carried passengers to the Exposition from the Potrero District via Van Ness Avenue; from downtown via the new Stockton Street Tunnel; and from the Ferry Building, not to mention the lines along Chestnut and Greenwich Streets. This dense configuration of lines is especially significant given the utter lack of service in other regions of the city, as discussed, and is made prominent on maps: as seen in Figure 1, the lines run so close to one another that their printed labels almost bleed into one another. At the same time, several of these lines were temporary, revealing that they were not meant to function as long-term infrastructural improvements. For example, the Columbus Avenue ‘J’ line only ran from February 10, 1915, to June 1, 1916, as it brought riders from the ferries to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition grounds (9). Lasting less than a year, this line was necessarily situated in its temporal and political context, deeply entwined in the Exposition and the drive to present the new San Francisco to a national and international audience.

It is clear that serving the fair was a massive priority that overtook all others. Here, transportation’s most basic function came back into play, in conversation with image-building ideology: an expansion of transportation meant that more people could reach the Exposition, which in turn meant more money for the city and a broader potential reach for San Francisco’s influence (10). The construction of streetcar lines, in other words, was particularly important for how it would boost the city’s image, rather than the practical lived experience of its local population. The critical importance of transportation to the PPIE also came through in the choice of its location. One of the proposed sites for the PPIE was the area along the Islais Creek (now Alemany) corridor. This might seem like a strange choice—the 1910 proposal included damming the creek to create a lake—but was favored by many because of the three railroad lines and local streetcar lines in proximity. These were thought to be able to easily transport multitudes to and from the Exposition. Ultimately, the Panama Pacific Exposition Company chose the Harbor View area (now the Marina) for its views of the bay, but as we have seen, the need for transportation would remain a pressing issue.

The issue of municipalization was certainly part of this lived experience, and it is notable that it is obscured on maps of the Exposition in comparison to maps of the city at large. Maps of the city analyzed in this project largely distinguish between Muni lines and those owned by the United Railroads; however, maps that explicitly show or refer to the Exposition, such as Figure 5 and Figure 8, do not differentiate between private and public lines. All of the lines shown on the latter belong to Muni, but one would never know this without supplementary sources. Whether this was a choice made for purposes of simplification or to purposefully distance the Exposition from the issue of municipalization is unclear. However, this difference certainly aligns with debates at the time about what municipalization could, or could not do, for the city’s image. For Exposition directors, the fair’s temporary lines were decisively not about expanding—and thus showing support for—municipal ownership (11). Concerned only with the success of the Exposition, they hoped to remain neutral on the issue, and some even resented city supervisors who tried to use the fair as a way to advance their goals.

On the other hand, maps that did emphasize municipal lines as distinct from private ones align with attitudes toward municipalization as a distinct advantage as San Francisco attempted to set itself apart and establish its power. San Franciscans saw that other West Coast ports now rivaled the city’s relative supremacy and understood that “measures as unusual as municipal ownership of transit might be needed to gain advantage for the city in the more competitive twentieth century,” in the words of author Mark Ciabattari (12). In an era where officials and locals alike were directed towards an interest in the city’s growth, the people of San Francisco felt that the responsibility was theirs to provide transit to, and thus ensure the success of, the Exposition. In either case, Muni was a means of presenting San Francisco as prosperous, cosmopolitan, and distinct; of providing a certain experience to those visiting the city for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, which visitors would carry back home and recount.

Streetcars bring visitors to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition at the San Francisco Ferry Building.

Photo: OpenSF History / wnp36.00728

Conclusion

It is clear, then, that the function of Muni in its first five years was not only a spatial one nor only a locally political one. It was at once a symbol of civic pride, a vehicle for projecting identity, and a key player in San Francisco's strategic narrative—a tool put to work in service of the appearance of prosperity, which had the potential to ensure the city’s continued power into the twentieth century. After the earthquake, what was once the most powerful city on the Pacific Coast was thought to have died, but with every passing streetcar, every dollar put into tourism and the Exposition, the possibility stood that Muni would put the city back on its feet.

The San Francisco of today is at a similar turning point. The city’s national reputation has plunged, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic; it is increasingly thought of as crime-ridden and unsanitary, its downtown areas left abandoned. Though locals understand that the reality is more complex, it is the outside narrative that matters if San Francisco is to fully recover its lost tourism traffic. What will it take to correct the city’s perceived course? By considering Muni’s early years, we can gain a new perspective on the relationship between public infrastructure, city image-making, and the aspirations that shape the urban experience. As San Francisco residents and officials alike defend their city, it is possible to look to history for clues in considering the narrative potential of the utilities and services that often blend into the landscape. For just as it is clear that Muni’s role transcended the pragmatic concerns of the day, we cannot underestimate urban infrastructure in how it helps to define and disseminate the stories we tell about our cities and ourselves.

Notes

1. Perles, Anthony. The People's Railway : the History of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Glendale, CA: Interurban Press, 1981.

2. Cameron, Roy S. History of Public Transit in San Francisco, 1850-1948. San Francisco, CA: San Francisco Transportation Technical Committee, 1948.

3. Segal, Morley. “James Rolph, Jr., and the Early Days of the San Francisco Municipal Railway.” California Historical Society Quarterly 43, no. 1 (1964).

4. Ibid.

5. Dyl, Joanna L. Seismic City: An Environmental History of San Francisco’s 1906 Earthquake. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2017.

6. Ibid.

7. Rast, Raymond W. “Tourist Town: Tourism and the Emergence of Modern San Francisco, 1869–1915.” PhD diss., University of Washington, 2006.

8. Ibid.

9. “Municipal Railway Lines of San Francisco, Cal.” Map. In The Municipal Railway of San Francisco, 1912-1921, by San Francisco (Calif.) Bureau of Engineering and M. M. O’Shaughnessy, 118. J.A. Prud’homme Composition Company, 1921. Table accompanying map.

10. Markwyn, Abigail M. Empress San Francisco : the Pacific Rim, the Great West, and California at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press, 2014. E-book.

11. Ibid.

12. Ciabattari, Mark. “Urban Liberals, Politics and the Fight for Public Transit, San Francisco, 1897-1915.” New York University, 1988.