Seeing the Elephant in Seattle

Historical Essay

by Chris Carlsson, 2000; originally published Red and Black Notes from Toronto, Canada.

At the end of November, 1999, thousands of protesters converged on Seattle, Washington, to protest the World Trade Organization's meeting. Hundreds of San Franciscans headed north to join the protest, and this is one account, written a couple of months after the historic shutdown of the WTO took place, Nov. 30-Dec. 5, 1999. For a more comprehensive and multi-voiced look at the events of that moment, this website is a great place to go: https://www.shutdownwto20.org/.

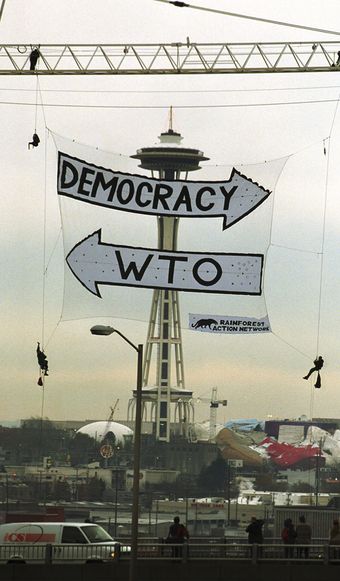

Photo: This is What Democracy Looked Like

Showdown in Seattle, the WTO, the Protest of the Century. Well, it's been more than a month since the exciting events in Seattle. Many of us who were there are still energized by it, but there's no mistaking the sense that it's all fading away. What seemed so remarkable and so unprecedented on November 30, the physical stopping of the WTO meeting by thousands of protesters clogging the streets of Seattle, has been reported, discussed, analyzed, argued, categorized, marginalized, and subjected to the self-serving spin of everyone from network pundits to leftist militants. The breathtaking thrill of participating in a quasi-insurrectional experience is harder and harder to remember or hold on to as the time passes.

Precisely because it is so difficult to recognize and hold on to the meaning of our own experiences, it is crucial that we go beyond the anecdotal memoirs and newspaper clippings to define the WTO/Seattle uprising in terms of our own history. Part of the beauty of Seattle, and equally part of why discussing it is already rather difficult, is the fact that the events in Seattle are impossible to define from any one perspective. If there was ever a sophisticated range of voices, experiences and ideals that came together to create a whole much larger than the sum of its parts, it was the WTO/Seattle protests. This multitude of perspectives leaves us facing the predicament of the Blind Men and the Elephant. Each of us has our own idea of what happened and what it means. Attempts to find a deeper understanding, or to situate it in terms of any given frame of reference, threaten to subsume important alternative understandings.

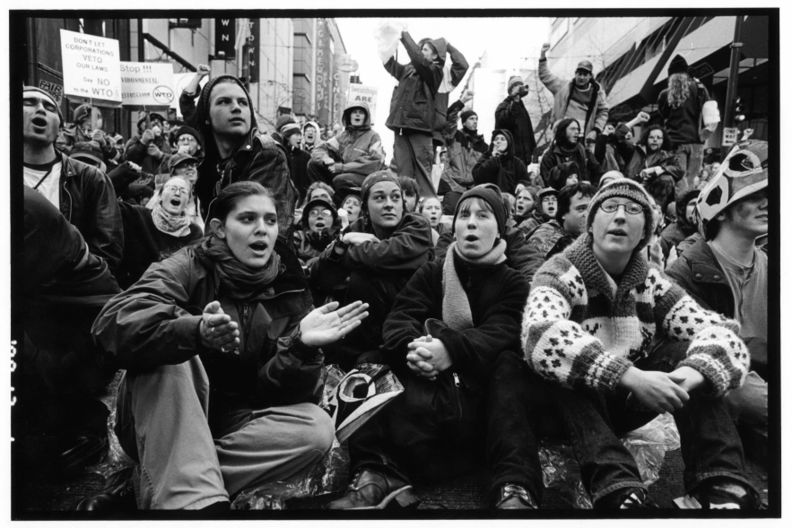

Dozens of sit-ins and blockades confronted delegates and police on the morning of November 30, 1999.

Photo: David Bacon

Police rolled out this armored personnel carrier, among many other military-grade weapons, during the protests.

Photo: Bill Stender

In spite of this inherent difficulty for analysis, I think there are some basic truths about this story that bear notice and perhaps even celebration Firstly, ten years after the collapse of the eastern bloc, and a sustained period of ruling class euphoria that we had reached "the end of history," our actions in Seattle are an emphatic rebuttal to that nonsense. Certainly Seattle did not come out of nowhere, but it did break a media monopoly that has shaped our consciousness of what is going on in the world and what it means. Even during the past decade’s self-congratulatory New World Order, history has made itself felt everywhere from the Zapatistas in Mexico to the massive strikes in South Korea that helped precipitate the collapse of major industrial firms in that country as well as provoking what has been called the Asian financial crisis. Civil wars have torn apart societies from Africa to the Balkans to Asia. Class divisions in every country have been exacerbated as ruling elites have extended their power and wealth to unprecedented extremes. As their privileges have been augmented and extended, their increased control over news and reporting has led to a widespread blackout on any news that contradicts the feel-good, go-go happy news of endless prosperity and meritocratic success.

Seattle shattered that illusion, at least temporarily. Given the speed with which the daily news “forgot" the whole story (which comes as no surprise, after all), those of us who made Seattle happen, and understand it as having a deeper meaning than just a confused bump in the road to an inevitable corporate globalization, have to keep the story alive, keep the discussions that flowed from it going forward, deepening and learning.

The ruling class ideology of endless prosperity and growth in a democratic capitalist world of "free" countries has suffered a slap across the face in Seattle. History has asserted itself. But what does history mean exactly in this context? Specifically, history means the inevitable re-emergence of class conflict. Seattle was many things to many people, but everyone there in opposition to the WTO knew that their interests were opposed to the corporate agenda for unfettered "free markets" and capitalist development. People from all walks of life, all ages, races, and nationalities, came together to raise their specific concerns, but for once saw that their issues were fundamentally connected to their fellow protesters and their issues. Thus the now famous slogan "Turtles and Teamsters: Together at Last" embodies a profound unity among people fighting for decent lives as workers, people fighting for a healthy relationship to global ecological well-being, people fighting sweatshops and child labor, people fighting to save old-growth forests and stop toxic waste dumping, people fighting to save subsistence agriculture and family farms, and so on.

It was absolutely exhilarating to be in the midst of this polyphonous cacophony. For anyone who has been politically active during the long dark era of the past two decades, the events in Seattle were a Rip van Winkle-like experience of awaking from a long somnambulistic slumber. After sleepwalking through the greatest speedup in human history, the mad descent into barbarism represented by "smart wars" in the Middle East, genocide in Rwanda, ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, slaughter in Indonesia, the rampant depletion of forests, fresh water, air and land, finally the streets were filled with well-informed, committed, self-disciplined, passionate people envisioning a very different life. The thousands of participants in Seattle represent an important development, especially in U.S. history. Working people came together to contest trade policies being negotiated behind closed doors. More importantly, in the fight over trade policies, the people in the streets knew that their situation was fundamentally allied with people in other countries being victimized by the same policies.

It is an old piece of Marxism that the working class is united by capital. Originally this analytical point explained how subsistence farmers, once evicted from their lands by the process of enclosure, found themselves as factory workers, and eventually developed new forms of struggle based on the new unity experienced on assembly lines and in working class urban slums. Since the early 1970's, capitalist globalization has ripped apart working class communities in the U.S. rustbelt, old industrial centers in Europe, and finally even destroyed the industrial foundation of working class life in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Globalization has moved production to low-wage countries around the world.

Meanwhile, urban life has undergone unprecedented transformation as working people have been uprooted everywhere and found themselves hurled from place to place in search of work and a living. Stable neighborhoods and communities have been broken down by this transience, made worse in many places in the U.S. by so-called "redevelopment" which has generally targeted working class communities which were home to distinct subcultures in the working class (such as African-Americans, retired port workers, etc.). One might argue that the quiescence of the past two decades has been a result of the success of ruling class policies in dismembering working class communities that had a memory of resistance, and the know-how to carry it out. Of course, trade unions, liberal politicians, mainstream environmental and feminist groups, all played important roles in demobilizing and demoralizing pockets of social opposition, too.

The Seattle/WTO meeting brought all these diffuse and fragmented constituencies back together in a unified front against the most tangible and obvious expression of global capitalist governance. Although the idea of class, especially working class, is not widely understood or accepted in U.S. culture, the movement that discovered itself in Seattle is fundamentally a working class movement. The people in the streets may identify themselves more formally with their cause, whether it be ecological or human rights or what have you, but you can be sure that few if any of them are anything in their daily lives but wage workers. In any case, the people in the streets of Seattle articulated a sophisticated understanding of the new global political situation, and saw their issues as transcending borders, workplaces, industries and populations. This alone is an earth-shattering development, and one that you can be sure has inspired a great deal of counter-planning by ruling class strategists. The machinations of politicians and trade union bureaucrats will inevitably confuse and distract us as we try to go forward from our victory and breakthrough in Seattle. But the experiences that people had in the streets cannot so easily be swept aside.

Direct Action Matures

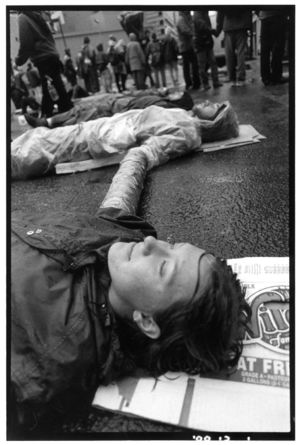

Thousands of people between the ages of 17 and 25 had their first ever experience of real politics, of nonviolent direct action as a powerful force of mass political action, of police repression and street fighting. The success of the Direct Action Networks strategy to shut down the WTO meeting on November 30 was as surprising to the members of the Network as it was to the police, media and the WTO ministers themselves.

Lockdown techniques used metal tubes and tape, which took hours to disentangle; given that such lockdowns were present all over downtown Seattle, the blockade was surprising successful.

Photo: David Bacon

Much has been learned during the last twenty years of direct action at nuclear and military facilities around the country. In 1979 the Boston-based Clamshell Alliance staged a major attempt to occupy the Seabrook, New Hampshire nuclear plant site, while Abalone Alliance affinity groups tried the same in 1980 and 1981 at Diablo Canyon, California. Police and state troopers repulsed those efforts with relative ease. Dozens of sit-ins and civil disobedience mass arrest actions have since been carried out at Rocky Flats in Colorado, Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, the Nuclear Test Site in Nevada, and dozens of other sites around the country. Slowly but surely the skill and tactical savvy of the protesters has improved. A couple of years ago, forest protesters got national attention for sitting in a congressman' office in northern California, their arms locked inside metal tubes, leading the local sheriffs to apply pepper spray under their eyelids with cotton swabs.

That lock-down technique, augmented by cement and chicken wire, and employed by several dozen affinity groups of 5-25 people in many locations simultaneously, proved to be too much for the police in Seattle. The inspiring courage of the direct action activists helped them survive frontal assaults and chemical attacks by the police, who eventually withdrew demoralized. Intensive preparation and role-playing had readied the demonstrators for the counterattacks they faced. Many had come with gas masks. Every affinity group had its own medical and legal auxiliary, the medics bringing water and first aid to those most severely attacked by the police. It was a brilliant demonstration of a self-organized "army" of peaceful, determined protesters who had made elaborate contingency plans and organized the whole thing from the bottom up through the tried-and-true structure of affinity groups.

The extensive and intensive training that preceded the November 30 day of action, combined with the super-accelerated learning experience of living through that day and the following ones, sets the stage for a new generation of activists. The thousands of young people who had their first experience in Seattle could have hardly had better training, either from the tactical side or from the political education side. It was also an inspiring, confidence-building experience for hundreds of us who have organized politically (and largely ineffectively) for the past two decades.

Tear gas filled the streets on November 30, 1999.

Photo: Bill Stender

Despite heavy tear gas usage, demonstrators held their lines and successfully blockaded the first day of the World Trade Organization ministerial meetings.

Photo: Bill Stender

Counter-Propaganda

The galvanizing success of that week in Seattle cannot be easily drowned in propaganda. The Independent Media Center, the grassroots counter-information system that reached a new level of sophistication in Seattle, is generating dozens of videos, newspapers, flyers and books. Based in a storefront in downtown Seattle, unfunded and lacking any formal staff, the Indy Media Center provided a focus for over 200 people participating in a news gathering operation that sent out dispatches throughout the five days of the protests. Online streaming video and audio went out over the Internet, while a half-hour documentary was produced each night and sent out by satellite to a network of independent cable tv stations around the country. Those five video half hours are now circulating in thousands of copies, being shown at public screenings, classes, and living rooms all over the country and the world … carrying the powerful experience well beyond those who immediately lived it but even more crucially, creating a representation of the Seattle protest that stands in permanent antagonism to the myriad attempts by pundits of the left and right to narrow its meaning to their own agenda.

A daily newspaper was produced out of the Indy Media Center, along with dozens of radio programs as well. The Independent Media Center succeeded in breaking the blockade of information usually thrown around an event like this by the mass media, who did their part by emphasizing the actions of a few dozen window-breakers over tens of thousands who remained paradoxically peaceful in their unambiguous war against the WTO and its delegates. (An Italian journalist, Pierluigi Sullo, said "The medium, beyond words, is nonviolent struggle, which, as we have seen, does not mean unwarlike struggle.")

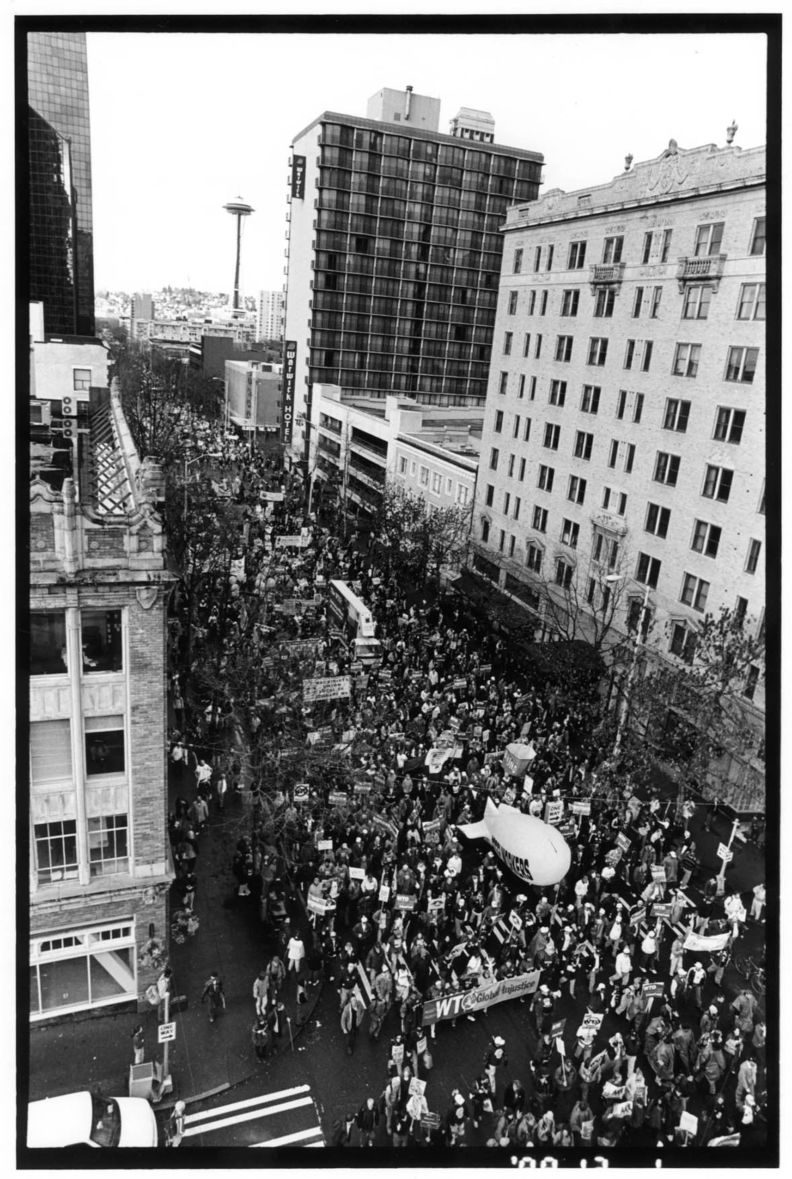

Thousands clogged the streets of downtown throughout the early hours of November 30, 1999, denying WTO delegates any chance to get tot he convention center.

Photo: David Bacon

The San Francisco-based group "Art and Revolution" seen here dancing in the streets during the WTO protests.

Photo: Bill Stender

During the darkest times of the Soviet Union, when secret police sought out dissidents who painstakingly typed up each and every copy of underground manifestos (called samizdat), the power of those dissident publications went a long way toward undercutting the credibility of the ruling party. In the post-Cold War era in the U.S., underground media is not seized because this culture uses a more sophisticated form of repression: pretend such alternative views simply don't exist. Drown them in the incessant roar of One Big Channel of Corporate Infotainment 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The Seattle videos, though, are a great example of a new grassroots system of undercutting the centralized control of a few media corporations. As the videos, documents, and personal accounts slowly circulate around the country, the credibility and authority of the current "order" erodes.

The power of camcorders and computers was thoroughly harnessed by an anti-corporate, anti-capitalist media in the service of the broad and diverse popular movements that came together in Seattle. For future political campaigns, rallies, even for helping a day-to-day attack on the infotainment monopoly of the media conglomerates, the Indy Media Center in Seattle was a vitally successful experiment that far out-performed anyone's most optimistic fantasies. The financial and personal resources needed to make this ad hoc phenomenon an ongoing presence in U.S. society are not in place. The Seattle experience was a wonderful demonstration of just how much techno-wealth and know-how exists, and how easy it can be to divert it to other ends than that for which it was originally intended.

Refusing Automation Down on the Farm

The day before the WTO shutdown, Monday the 29th, a smaller march of about 2,500 people converged on a McDonalds in downtown Seattle where French farmers passed out 2 kilo blocks of delicious Roquefort cheese. Numerous vegans in the crowd turned down the smelly largesse with dismay, but some of us were delighted to be freely sharing some of the worlds finest cheese with its makers, as a public repudiation of the vapid fare served up in fast food joints across America. Family farmers from Canada, rural U.S., Japan, and France all spoke out against the big multinational food companies who are bent on driving family farms, organic agriculture, and even traditional low-tech farming into bankruptcy. Meanwhile a couple of thousand of the people gathered against the WTO and global capitalism lent their presence to a raucous warm-up to the next day's Main Event.

Environmentalists, unionists, farmers, activists of various stripes, found an easy unity in their wide opposition to the latest technological developments in agriculture, namely genetically modified foods. The entry of bioengineering into the generations-long process of capitalist centralization and intense automation has in its own way brought together an unprecedented spectrum of opposition. Regrettably, a good deal of this upsurge against bio-engineered food is falling into the liberal trap of basing its opposition on mere food safety. No doubt the campaign planners think they'll be able to mobilize many more "apathetic" Americans by scaring them about their food. But this is a recipe for failure. Reducing the issues surrounding genetically modified foods to one of "safety" pits corporate mercenaries in white lab coats against underfunded, earnest gadflies plaintively seeking media attention for their "sky is falling" rhetoric. This serves to accept (or at least to ignore) the deeper problem of genetically altering the web of life, destroying the integrity of distinct species, and doing such dramatic things without any idea of what the outcome might be for planetary ecology. Essentially, the food safety argument focuses (out of expedience, I suppose) on our status as guinea pigs for agribusiness, but in so doing, casts aside the much larger problem of subjecting the entire planet to bizarre, unpredictable, dangerous experiments in genetic manipulation.

The convergence of constituencies around opposition to Monsanto and Terminator seeds and genetically modified foods in general is better seen as a profound refusal of the "normal" trajectory of capitalist development. Since the original uprooting of farmers from common lands over two centuries ago, the expansion of capitalist production has made food production more and more remote, while enforcing a rigid separation between urban dwellers and nature, only vaguely assuaged by parks and camping trips to the mountains. Perhaps the contemporary booms in organic foods, community gardening, habitat restoration, and yes, food safety, are all manifestations of a quest to overcome the old division between city and country? The incredible distances that food travels is part of the impetus for its genetic modification towards greater durability and longer shelf lives. As we reject genetically modified foods we also inherently embrace a return to local production, and a greater integration with natural resources in our immediate environment. Perhaps this new "food activism" represents a re-appropriation by workers of their own activity, a making time for digging in the dirt, growing and preparing food, re-establishing a closer connection with natural cycles of crops and seasons. Its important to reject corporate manipulation of genes and germ lines, the monopolization of seeds and so on. Harder to understand and embrace is a crucial rejection of a helpless detachment from the real decisions that shape our lives, a new insistence on our right to decide together the limits to the marketization of life itself. In the streets of Seattle, such larger issues were vitally alive.

The Elephant In Seattle Has Many Sides

The debates which erupted during and after Seattle among activists are a welcome blast of political wind through the narcoleptic stillness of our apolitical culture. Some nonviolent protesters fell into a familiar self-righteous anger at the autonomists who attacked corporate property. This has led to debates in newspapers and different forums around the country about the meaning of violence, the strategic importance of a focus on the unassailable behavior of the demonstrators (as opposed to the ongoing "normal" behavior of the corporate targets of the protests), the tactical value of a self-disciplined, broad-based movement for attracting new participants, and so on Any social protest movement has to allow for a real diversity of strategic and tactical choices. It was curious to see various organizers claim that their choices of nonviolence up to and including respect for property was somehow a rule that anyone who showed up in Seattle was ethically bound to respect.

Several dozen or several hundred people joined in the protests with a clear conviction that attacking the storefronts of multinational criminals like The Gap, McDonalds, Starbucks, etc., was a perfectly legitimate form of political expression. Their detractors, who deliberately denied WTO delegates physical access to their meeting, thus taking away their freedom of mobility, assembly and speech, saw the trashing of stores as a major public relations setback, or worse, a complete moral failure.

The AFL-CIO march through downtown Seattle.

Photo: David Bacon

The AFL-CIO union leadership organized a large demonstration of unionists, but then tried to keep them away from the Direct Action Networks occupation of downtown at the precise moment when 35,000 unionists would have had an incredibly supportive impact on the whole campaign to stop the WTO. Inspite of organized monitors attempts to turn the union march away, thousands of rank-and-file workers poured into the streets in support of the mornings seizure of downtown. Joined by student, leftist and environmentalist marchers, the front-line blockaders were reinforced in their efforts; the surge of new people into the streets during the afternoon consolidated the days victory and made possible the victorious retreat in the evening, in spite of the dubious directives from national union leaders.

The peaceniks and the trade union leaders both represent a version of loyal opposition. The anti-WTO demonstrations coincided with the end of a long period of neo-liberal loosening of government intervention and non-market controls. The de-control of the last two decades has led to an unprecedented concentration of capital, the most recent merger of AOL with Time-Warner being only the latest in a long line of such events.

The protests in Seattle are in an ambiguous relationship to this historic moment. Many protesters were clearly anti-capitalist and ready to overthrow the system without a clear idea of how else we might organize a complex material life for the planets six billion inhabitants. But a number of organizers and participants seek to reform the system, to the point of beseeching the globalizing technocrats for a seat at the table. For these reformers, "irresponsible" behavior by demonstrators hurts their credibility. In fact, if they prove unable to "control" it, their usefulness to world capitalism is harder to justify.

Moreover, the union leaders and "progressive" lobbyists all work comfortably in a world of hierarchical organization, deal-making, and reasonable negotiation. When groups outside of that world take action on their own, for their own strategic goals and with their own tactics, it threatens the careful attempts by reformists to bring the neanderthals into a process of change that will ultimately stabilize the world economic system for the benefit of future profitability. The authorities are working as hard as we are to digest the lessons of Seattle. I expect they will devise pre-emptive strategies that involve greater surveillance, more police and military offense, and more counter-intelligence activities (disinformation, sowing discord, agents provocateurs, and so on). Our own thinking and planning will have to go beyond what we've done before and find new ways of consolidating and carrying forward a coherent opposition. An important part of that is to build on the amazing connections that were made in action in Seattle to begin a far-reaching public discussion of the world we want to live in.

It is much easier to be against, than it is to know what were fighting for. The shape of a society beyond the economy, one in which we freely and democratically choose how we live, is an untried creative challenge. How do we provide adequately for everyone, live in a new conscious harmony with global ecology, repair the enormous damage to the planet and our psyches? How will we overcome the entrenched power and violence of a smart and vicious ruling class with the passion, good will, and convivial brilliance we tasted so briefly in Seattle?

An old saying dating from the Civil War and then the huge migration west was to "see the elephant," meaning you personally had seen something quite remarkable. As we grope to understand the political and social meaning of our experiences in Seattle, there's no doubt that we all saw the elephant.

ILWU members marching in Seattle, 1999.

Photo: David Bacon

Art and Revolution standing amidst large seated crowd in downtown Seattle intersection, November 30, 1999.

Photo: Bill Stender