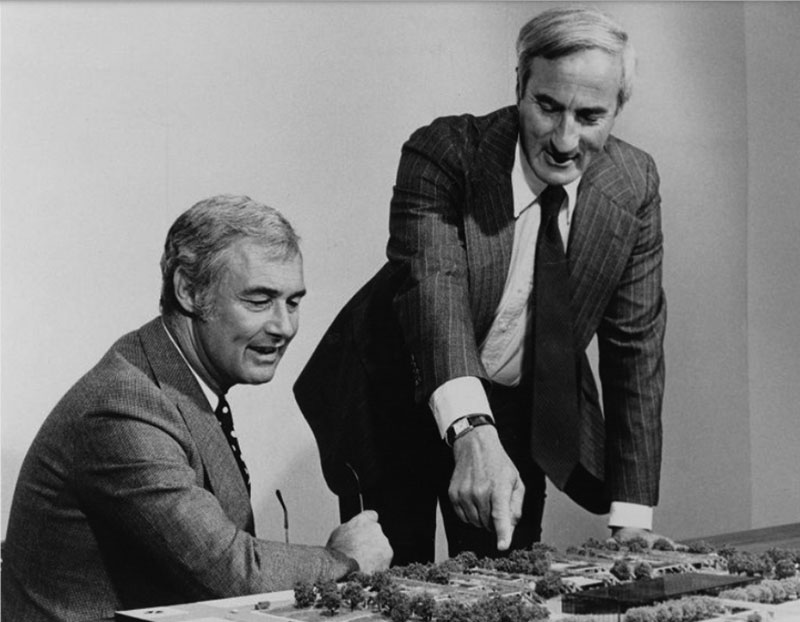

San Francisco Housing Authority and Mayor Moscone

Historical Essay

by John Baranski

This excerpt originally appeared in "All Housing is Public," Chapter Seven of Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco (see below for copyright and book information)

Mayor Moscone and his chief administrative officer Roger Boas gazing at the model for Yerba Buena Gardens, 1977.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, AAC-0732

San Francisco’s political and economic leaders envisioned the city’s housing and redevelopment much in the same ways as did HUD officials. The election of Mayor George Moscone (1976–1978) and a progressive San Francisco Board of Supervisors (Ella Hill Hutch, Gordon Lau, Harvey Milk) resulted in part from a wave of voter discontent with previous political elites, who put redevelopment and economic growth before the needs and desires of ordinary residents. But early optimism soon gave way to local and national realities. In July 1976, Moscone spoke at the SFHA Commission meeting, where he praised the agency for its decades of service, its awards for senior housing designs, and its provision of housing and social programs to the city. Then he offered several recommendations. The SFHA needed to reduce labor costs and, although it would be challenging in the current budget situation, modernize the 5,500 SFHA family housing units. He recommended improving SFHA–tenant relations, acknowledging that this

was no easy task. Many complaints by tenants concern the condition of their housing unit and the lack of services. On the other hand, your ability to respond to these complaints is severely limited by inadequate operating funds provided by the Federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Moscone commented on national public housing trends and urged the SFHA to ensure “greater involvement of tenants in the management of public housing projects.”(11)

If Moscone desired greater tenant involvement in the SFHA, the same was not true of other city agencies. As scholar Chester Hartman noted, Moscone’s appointments to the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency did “little immediately or in the long run to alter the city’s basic redevelopment activities.” After Supervisor Dan White murdered Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, Supervisor Dianne Feinstein became mayor and promptly replaced Moscone’s redevelopment agency appointees with officials who maintained a pro-development agenda that did not value the homes or communities that stood in the way of their projects. Under the Moscone and Feinstein administrations, community groups would, to quote Hartman again, “decry, with justification, their exclusion from the decision-making process, and the agency continued to approve projects despite opposition from residents and neighborhoods in its development areas.” The Planning Commission, as the other housing-related agency, typically provided the technical and legal legitimacy for redevelopment agency projects.(12)

When Reverend Boswell’s seat on the commission became vacant, Mayor Moscone appointed Reverend Jim Jones. A rising political star, Jones had built a large following through his Peoples Temple organization by using a populist, Christian message and by providing social services. A mayor’s office biography described Jones “as an uncompromising foe of racism and social injustice” and as someone who created programs “that have rescued many hundreds from extreme poverty, drug addiction and other oppressive conditions.”(13) Donald Field, a member of the Peoples Temple, said, “One of our objectives is to communicate the needs and frustrations of the ‘little people’ who are really the backbone of the community.”(14) As commissioner, Jones noted in a discussion about the quality and quantity of public housing that “if this country cannot provide adequate housing for everyone, then it is up to the Commissioners to ‘raise a bit of thunder’ to see that funding is available to provide ‘Cadillac housing’ for everyone.”(15) When commissioners elected Jones to chair the SFHA Commission, with tenant Cleo Wallace as vice chair, the largely tenant audience gave them a standing ovation. Few at the time imagined, of course, the deadly tragedy in Guyana that Jones and his church would produce.(16)

previous article • continue reading

Notes

11. SFHA, Minutes (July 29, 1976).

12. Hartman, City for Sale, chapter 11. Quotes on 277. Also see Ocean Howell, Making the Mission: Planning and Ethnicity in San Francisco (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

13. “Housing Authority picks Rev. Jones as Chairman,” San Francisco Examiner (February 25, 1977).

14. “Peoples Temple,” Donald Field letter to editor, San Francisco Examiner (June 20, 1977).

15. SFHA, Minutes (January 27, 1977).

16. Moscone had lobbied to make Jones chair. “Housing Authority Picks Rev. Jones as Chairman,” San Francisco Examiner (February 25, 1977). For Jones’s life, see David Chidester, Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004).

Excerpted from Housing the City by the Bay: Tenant Activism, Civil Rights, and Class Politics in San Francisco by John Baranski, published by Stanford University Press. Used by permission. © Copyright 2019 by John Baranski. All rights reserved.