STRIKE!... Concerning the 1968-69 Strike at San Francisco State College

Historical Essay

compiled by Helene Whitson

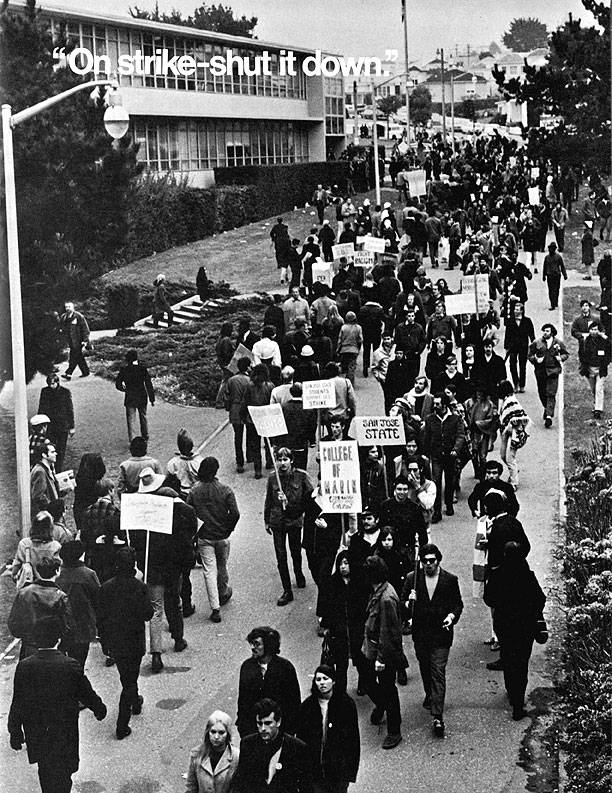

Protesters march near 19th and Holloway on SF State campus, 1968.

from "Crisis at SF State" © 1969 by Insight Publications

| A college established in the final year of the 19th century, San Francisco State College found itself confronted by the idealism of the youth of the 1960s and anger over academic bureaucratic policies. From November 1968 to March 1969, the words “On strike! Shut it down!” rang out daily from the campus of San Francisco State College. The five month strike sought to expose the racism and authoritarianism found on campus and demanded increased student of color representation, as seen in the demands of the Black Students and Third World Liberation movements. As a result of strikers efforts, the Departments of Black Studies and Ethnic Studies were founded at SF State. |

"On strike! Shut it down!" From November 1968 to March 1969, those words rang out daily on the campus of San Francisco State College. Like clockwork, between noon and 3 p.m., striking students would gather at the Speaker's Platform on campus for a rally, then turn in a mass and march on the Administration Building, intent upon confrontation with President Smith or Hayakawa. The strike at San Francisco State College lasted five months, longer than any other academic student strike in American higher education history, and, miraculously, was less violent than any that were to come. Why did this strike happen in San Francisco, a sophisticated, cosmopolitan city, known for its tolerance? Why did it happen at San Francisco State College, an innovative, liberal, four-year institution that was comparatively unknown?

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/As_P3DueKrY?rel=0" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; encrypted-media" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Local public television footage of the San Francisco State College strike.

San Francisco has been called "the city that knows how," an apt description of its progressive, stimulating atmosphere. From a frontier town on San Francisco Bay in 1849, the city has grown to a financial and cultural center, noted for its business acumen as well as its patronage of music and art. Visitors come from all over the world to experience its magical excitement. Through the years, the city has grown in size, population, and maturity, but has never lost its tolerance for new ideas.

At the turn of the century the city was still feeling its youth, with cobbled streets, fancy tan dies, lavish mansions, and elegant hotels and restaurants. During this era of sophistication the decision was made to open a normal school in San Francisco, and in 1899 San Francisco State Normal School was born. (An earlier normal school, the first in the state, had been established in the city in 1862, but had been transferred to San Jose in 1870.) The first president of the new school was Dr. Frederic Burk, a noted educator whose specialty was individual instruction. Dr. Burk had no qualms about putting new educational ideas and theories into practice, often taking on the traditionalists on the State Board of Education while promulgating his innovations.

As the city grew, so did the college. At first, the teachers were mainly women, and for twenty years or so there was a majority of women in its student body. San Francisco State Normal School supplied most of the teachers for the San Francisco Public Schools, as well as for school districts all over the state. In the early 1920's, more and more men began to enroll. In 1921, the college changed its name to San Francisco State Teachers College; by 1935 it was called San Francisco State College. Along with the other California state colleges, it became a liberal arts school.

During the 1930's the San Francisco State College campus was typical of other college campuses across the country. Although the depression hit San Francisco hard, as it had other American cities, there were dances and football games, and a superficial sense of innocence and cheerfulness. San Francisco, long a supporter of the rights of the working person, underwent a bitter, angry city workers' strike in 1934, but could still try to express that sense of tolerance for which it was known. Beneath the surface, however, San Francisco State College students were politically aware. In the late 1930's a group of students held an antiwar protest, a precursor of events to come. In the 1940's San Francisco State personnel and students did their patriotic duty and went off to war, some not to return. In the 1950's, San Francisco was caught up in the McCarthy hysteria, as was the rest of the country. Seven faculty members and two non faculty members were terminated for refusing to sigh the loyalty oath. By 1960, when protesters against the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings in San Francisco were washed down the steps of City Hall, San Francisco had become a gathering place for those who wished to test established and outmoded traditions and see change in American society.

The 1960's can be called the age of idealism in the history of American youth. There have been other periods of youthful idealism in American history, but never were there so many young people with the time, money, and energy to express their opinions as in the 1960's. The civil rights movement was underway in the South. Minority groups, especially blacks, were beginning to make strong, visible stands for their rights. To the west, rumblings of war were beginning to develop -- Vietnam. Students were concerned not only about their own rights and whether they would be drafted, but about the suffering people of Vietnam, who were being bombed and napalmed by American military might. They could not accept an American government that continued to bomb and strafe hamlets and villages in spite of protests at home. Students began to look at their own position in American society and wonder whether what they were learning in institutions of higher education had any relevancy to their lives, immediate or future. In 1966, the most idealistic youths in the country appeared in San Francisco -- the hippies.

They were convinced that love, sharing, and caring would solve the problems of the world: love and a flower would make it right. The idealism of San Francisco in 1965-1966 spilled over onto the campus of San Francisco State College. As a beginning librarian, I felt the electricity, the excitement, the sense of creativity and hope. Dr. John Summerskill, a youthful and liberal educator, had just been appointed president, and our college was going to go far in solving the problems besetting man and woman kind. San Francisco State College's Experimental College was one of the first in the country, a forerunner of many similar institutions across the land.

In May, 1967, some students went to Dr. Summerskill to protest the college's practice of revealing students' academic standing to the Selective Service Office. The academic bureaucracy was not at that time aware of how to handle questions and protests, although our neighbor across the Bay, the University of California at Berkeley, should have taught us some lessons. The students of earlier decades may have had quarrels with academic nit-picking or poor administrative judgment, but they did not feel they had the power to make their desires felt or perhaps did not care enough to carry a protest very far. Many students of the 1960's, however, came from comfortable middle-class families that had stressed the value of education, and they were convinced enough of the importance of their ideas to demand answers.

They were willing to take the time and effort to assert their beliefs. Furthermore, many minority groups were beginning to criticize higher education institutions for ignoring their special interests. Consequently, minority students were eager to demand consideration also.

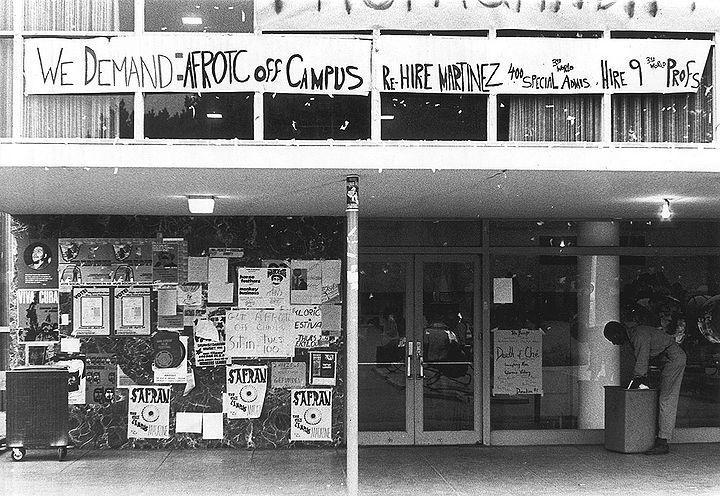

SF State cafeteria, site of organizing and speech-making prior to and during the strike.

Photo: Jeffrey Blankfort

The academic machinery was creaky and unused to being called to account for its actions. Although the issue may now seem minor, those students protesting the "insensitive administration's" willingness to cooperate with the Selective Service Office held on tenaciously. They wanted the policy stopped, and they would protest until it was stopped! When Chancellor Glenn Dumke ordered its continuation, the students felt that their rights and beliefs were being ignored; the action of the Chancellor's Office reinforced the feeling that higher education was totally unsympathetic to student ideas and irrelevant to their needs.

As the power of minority students began to appear on campus, racial divisiveness became a problem, marring the earlier sense of idealism. Some white students began to express hostility to the growing use of student funds for black student education and activities. The editor of the student newspaper, The Gator, was physically attacked by several black students after he wrote an editorial opposing outside funding for the college's "special programs," which included those of the Black Student Union. The first "Shut it down!" was shouted on December 6, 1967 when protestors objected to the suspension of the black students involved in The Gator incident. There were to be many more.

Mounting tensions on campus and failure to solve the student problems led the Trustees to request that Dr. Summerskill resign. In June 1968, Dr. Robert Smith, a professor of education, was appointed president. He too was to fall victim to the demands of the students that the problems of society be solved by higher education.

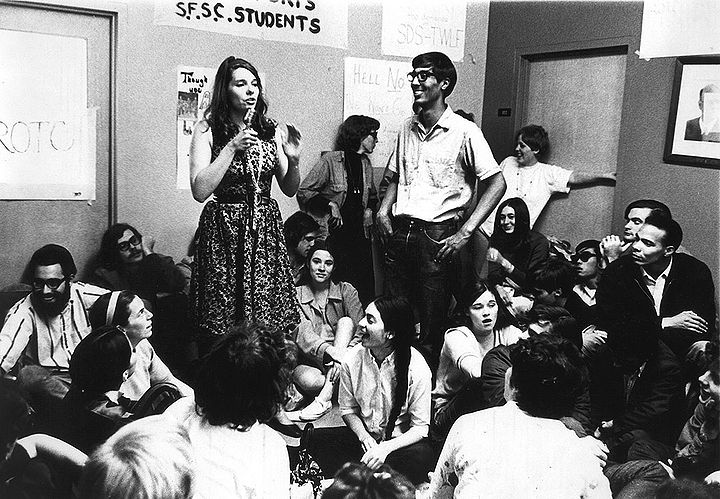

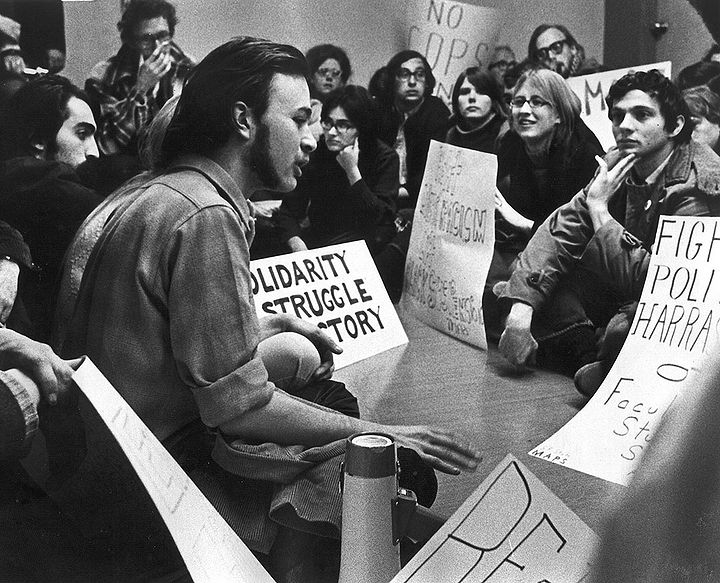

Sit-in during SF State College strike, 1968.

Photo: Jeffrey Blankfort

The suspension of English instructor (and Black Panther Party Minister of Education) George Mason Murray on November 1, 1968, was the catalyst for five months of confrontation and tension. George Murray was a graduate student in English and had been hired to teach special introductory English classes for minority students admitted to the college under a special program. At a Fresno State College rally, he allegedly had stated, "We are slaves, and the only way to become free is to kill all the slave masters." At San Francisco State College, he allegedly had said that black students should bring guns to campus to protect themselves from white racist administrators. The Trustees forced President Smith to suspend Murray. That did it! Black students and their white sympathizers viewed the administration's action as racist and authoritarian, and the administration itself as weak, controlled by conservative, uncaring politicians in Sacramento and Conservative, rich, white trustees in Los Angeles. They felt that the suspension was a perfect issue to illustrate the racism and authoritarianism found not only on college campuses, but actually established as a major tenet of the "American way of life." A protest against this action would bring to public notice some of the inequities in the words that American authorities preached and the deeds that they performed.

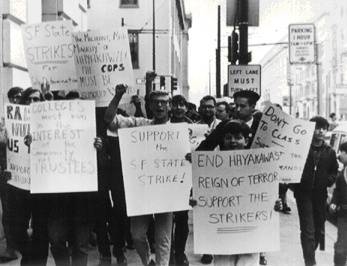

SF State protesters

Photo: Terry Schmitt

SF State Strikers

Photo: Terry Schmitt

President Smith tried to bring reason to bear on the matter, but was pushed by conservative Trustees on the one side and impatient, angry students on the other. He hold a three-day convocation on campus, during which all classes were cancelled and all members of the campus community came together to discuss the issues. Striking minority students submitted a list of demands to the campus administration:

Black Students Union

1. That all Black Studies courses being taught through various departments be immediately part of the Black Studies Department and that all the instructors in this department receive full-time pay.

2. That Dr. Hare, Chairman of the Black Studies Department, receive a full-professorship and a comparable salary according to his qualifications.

3. That there be a Department of Black Studies which will grant a Bachelor's Degree in Black Studies; that the Black Studies Department chairman, faculty and staff have the sole power to hire faculty and control and determine the destiny of its department.

4. That all unused slots for Black Students from Pall 1968 under the Special Admissions program be filled in Spring 1969.

5. That all Black students wishing so, be admitted in Fall 1969.

6. That twenty (20) full-time teaching positions be allocated to the Department of Black Studies.

7. That Dr. Helen Bedesem be replaced from the position of Financial Aid Officer and that a Black person be hired to direct it; that Third World people have the power to determine how it will be administered.

8. That no disciplinary action will be administered in any way to any students, workers, teachers, or administrators during and after the strike as a consequence of their participation in the strike.

9. That the California State College Trustees not be allowed to dissolve any Black programs on or off the San Francisco State College campus.

10. That George Murray maintain his teaching position on campus for the 1968-69 academic year.

Sit-in during SF State College strike, 1968.

Photo: Jeffrey Blankfort

Third World Liberation Front

1. That a School of Ethnic Studies for the ethnic groups involved in the Third World be set up with the students in each particular ethnic organization having the authority and control of the hiring and retention of any faculty member, director, or administrator, as well as the curriculum in a specific area study.

2. That 50 faculty positions be appropriated to the School of Ethnic Studies, 20 of which would be for the Black Studies program.

3. That, in the Spring semester, the College fulfill its commitment to the non-white students in admitting those who apply.

4. That, in the fall of 1969, all applications of non-white students be accepted.

5. That George Murray and any other faculty person chosen by non-white people as their teacher be retained in their positions.

The convocation allowed campus members to express their ideas, but the administration could not answer some of the student demands, and the students would not take "We can't" or "We haven't the authority" as an answer. The situation deteriorated further, and on November 26, 1968, Dr. Smith resigned.

Appointed as the acting President of the campus was Dr. S. I. Hayakawa, noted semanticist. Twelve days earlier, he had spoken out in a faculty meeting, urging faculty members to support Dr. Smith. His first action, which set the tone of his administration, was to close the campus. If the word "reasonable" can be used to describe President Smith, then "authoritarian" must be used to describe President Hayakawa. His administration would not accept change through intimidation. If students marched on the Administration Building, then he would see to it that the San Francisco police were there to handle the situation. San Francisco State College became international news, and Dr. Hayakawa became a symbol of authority and stability. He closed school a week early for the Christmas holidays, hoping that a "cooling off" period would take place.

San Francisco State College President S.I. Hayakawa.

Some faculty members were also extremely concerned with the situation on campus. Many of the more liberal ones were frustrated with the political climate in California ant the nation as a whole, and sympathized with the striking students. They felt that Governor Reagan was attacking higher education in the state, and that the Board of Trustees and the Chancellor were too rigid. (Chancellor Glenn Dumke had once been president of San Francisco State College, and had often been at odds with more liberal faculty members over various issues.)

These faculty members also felt that any decision-making powers they may have had in the past were quickly being usurped by the campus administration, under orders from the Board of Trustees. The members of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) local especially felt that the students had already taken risks and made stands for what they believed, and that they, the teachers, also had to take action. On December 11, 1968, more than fifty AFT members set up an informational picket line around the campus, while waiting for official strike sanction from the San Francisco Labor Council. On January 6, 1969, they began their official strike.

The next two and one-half months saw the same daily confrontations on campus and the same negotiations behind the scenes. Superior Court judges ordered the strikers to desist, yet the strike continued. Several tentative agreements were announced, but the strike went on. Finally, on March 20, 1969, a joint agreement was signed between "representatives of the Third World Liberation Front, the Black Students Union, and the members of the Select Committee concerning the resolution of the fifteen demands and other issues arising from the student strike at San Francisco State College."

Riot police at San Francisco State.

Photo: Terry Schmitt

The major points of the settlement were as follows:

Black Students Union

1. That all Black Studies courses being taught through various departments be immediately part of the Black Studies Department and that all the instructors in this department receive full-time pay.

Settlement:

a. All courses have been transferred with the exception of one in Anthropology and one in Drama.

b. All instructors employee full-time will receive full-time pay.

2. That Dr. Hare, Chairman of the Black Studies Department, receive a full-professorship and a comparable salary according to his qualifications.

Settlement:

a. The apparent failure to rehire Dr. Hare is irrelevant to the institution of the Black Studies Department. The Department Chairman shall be selected by the usual departmental process and Dr. Hare shall be eligible for selection.

3. That there be a department of Black Studies which will grant a Bachelor's Degree in Black Studies; that the Black Studies Department chairman, faculty and staff have the sole power to hire faculty and control and determine the destiny of its department.

Settlement:

a. President Robert Smith created a Black Studies Department on September 17, 1968.

b. The Trustees approved the granting of a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Black Studies on October 24, 1968.

c. On December 5, l968, the Council of Academic Deans recognized the Black Studies Department as having full faculty power commensurate with that accorded to all other departments of the College.

d. The College would establish a community board to provide community support and encouragement for minority programs. One of the functions of the board would be to recommend faculty appointments to the President. However, the board would have no legal authority.

4. That all unused slots for Black Students from Fall 1968 under the Special Admissions program be filled in Spring 1969.

Settlement:

a. One hundred twenty-eight E.O.P. students were admitted for the Spring 1969 semester.

5. That all Black students wishing so, be admitted in Fall 1969.

Settlement:

a. The College agreed to admit approximately 500 qualified non-white students for the Fall 1969 semester and was actively recruiting such students. There were also to be about 400 non-white students as special admittees.

b. The College committed itself to funding and staffing for an Economic Opportunity Program (E.O.P.).

c. The College agreed that parallel admissions standards are necessary for Third World people if the College is to fulfill

its educational responsibilities in an urban environment.

6. That twenty (20) full-time teaching positions be allocated to the Department of Black Studies.

Settlement:

a. 12.3 positions were allocated to the Black Studies Department (11.3 unfilled positions).

b. More positions would be allocated in accordance with need and available resources.

7. That Dr. Helen Bedesem be replaced from the position of Financial Aid Officer and that a black person be hired to direct it; that Third World people have the power to determine how it will be administered.

Settlement:

a. The College appointed a black administrator to the newly create position of Associate Director of Financial Aid. He would make the final decision in the College Work Study Program and would make final decisions on financial aid packages for all black students who wish their decisions made by a black administrator.

b. The Office of Financial Aids already had a Spanish-speaking administrator who would function in the same way as the black administrator.

8. That no disciplinary action will be administered in any way to any students, workers, teachers, or administrators during and after the strike as a consequence of their participation in the strike.

Settlement:

The Select Committee members, and representatives of the TWLF-BSU recommended the following to the President concerning all cases pending on March 17, 1969:

a. Students charged solely with acts of non-violence shall receive a written reprimand.

b. Students charged with "violent acts" shall, if found guilty by the hearing panel, receive a penalty of not more than suspension through the end of the Fall semester of 1969-70.

c. Students charged with instructional disruption shall, if found guilty by the hearing panel, receive a penalty of no more than suspension for the remainder of this (1968-69) academic year.

9. That the California State College Trustees not be allowed to dissolve any Black programs on or off the San Francisco State College campus.

Settlement:

a. This resolution was not implemented.

10. That George Murray maintain his teaching position on campus for the 1968-69 academic year.

Settlement:

a. This decision would be referred to the community advisory board.

Third World Liberation Front

1. That a School of Ethnic Studies for the ethnic groups involved in the Third World be set up with the students in each particular ethnic organization having the authority and control of the hiring and retention of any faculty member, director, or administrator, as well as the curriculum in a specific area study.

Settlement:

a. The College would endeavor to establish a School of Ethnic Studies to begin operation in the Fall Semester 1969. The College will need additional funding for this purpose.

b. The School will equal existing Schools of the College in status and structure.

c. The college would establish a community board to recommend faculty appointments to the President.

2. That 50 faculty positions be appropriated to the School of Ethnic Studies, 20 of which would be for the Black Studies program.

Settlement:

a. allocation of faculty positions to the School of Ethnic Studies will follow upon Spring planning and resources acquired by the College.

3. That, in the Spring semester, the College fulfill its commitment to the non-white students in admitting those who apply.

Settlement:

a. One hundred twenty-eight E.O.P. students were admitted for the Spring 1969 semester.

4. That, in the fall of 1969, all applications of non-white students be accepted.

Settlement:

a. Same as response to B.S.U. Demand #5.

5. That George Murray and any other faculty person chosen by non-white people as their teacher be retained in their positions.

Settlement:

a. Same as response to B.S.U. Demand #10.

FURTHER RESOLUTIONS

1. That a committee of students, faculty, and staff, ethnically mixed, be formed immediately to advise the College on how to teal with the charges of racism at the College. A first task for this committee will be to recommend procedures for dealing with claims of racism within the college.

2. That the procedure for appointing an ombudsman be started again and pressed to as rap it a conclusion as possible.

3. The College shall establish, through its Academic Senate and the Council of Academic Deans, a small committee to expedite decision making and action concerning all aspects of this agreement.

4. In recognition of the urgency of the present situation, we recommend that the Chancellor and Trustees expedite in every way possible the consideration of any requests for special resources presented by the College President which arise from the extraordinary needs of the College at this time.

5. In instances where differences of interpretation occur in the precise meaning of any part of this agreement, final and mutually binding decisions upon all parties shall be made by a three-man group composed of one person named by the President of San Francisco State College, one person named by the Dean of the School of Ethnic Studies and the Chairmen of the various Ethnic Studies Departments, and a third person selected by these two.

6. Staffing and admission policies of the School of Ethnic Studies shall be non-discriminatory.

7. Police should be withdrawn immediately upon the restoration of peace to the campus.

8. The state of emergency on campus should be rescinded immediately upon settlement of the strike, together with the emergency regulations restricting assemblies, rallies, etc.

9. The College shall resume planning for a Constitutional Convention and for a student conference on the governance of the urban campus.

10. The students and the administration together recognize the necessity of developing machinery for peaceful resolution of future disputes, arising from conditions or needs outside the terms of this agreement.

11. The student organizations signatory to this agreement and the College agree that they will utilize the full influence of their organizations to insure an effective implementation of this agreement.*

On March 20, 1969, the strike ended. Why did it happen? The answer may be found in part in the words of Dr. Walcott Beatty, Chairman of the San Francisco State College Academic Senate at that time: The campus is a microcosm of society. In 1968, American citizens all over the country, shaken by racial tension and the war in Vietnam, were examining their values to see whether the direction in which the country was heading was the way they wanted it to go. Perhaps at San Francisco State College, the idealism of 1966 was still holding on, the idea that students and faculty could express their thoughts and somehow change a society that hat become unwieldy and rigid, ponderous and oppressive. Perhaps that is what it was all about. For five long months, students and teachers fought for the ideals in which they believed, right or wrong. And, whether they won or lost (no one can really say who won or lost), the members of the San Francisco State College community had the opportunity and the duty to express those beliefs and principles for which they fought.

Strikers crowd campus entry path, 1968.

Photo: Tim Drescher

Americana game invented by SDS