Remembering A Police Riot: The Castro Sweep of October 6, 1989

Historical Essay

by Gerard Koskovich, 2002

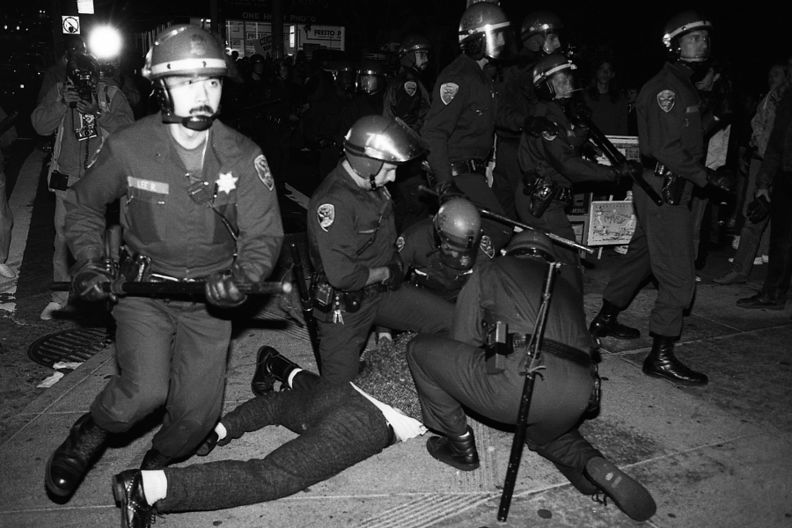

Scene from the Castro Sweep Police Riot of October 6, 1989 with police arresting Gilbert Criswell at the corner of Castro and 18th Streets.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

The rally at the San Francisco Federal Building that kicked off the ACT UP National Day of Action on Oct. 6, 1989.

Photo: Brian McNally

The Burton Federal Building is a bleak gray high-rise of glass and granite, an exemplar of Cold War modernism that marks a divide between the Beaux Arts ostentation of San Francisco's Civic Center and the gritty Polk and Tenderloin neighborhoods. On Friday, October 6, 1989, I arrived at the windswept plaza in front of the Federal Building in the sharp light of late afternoon to take part in "Living With AIDS and Fighting Back," ACT UP/San Francisco's contribution to a national day of AIDS protest. The organization was then in its heyday as a serious advocacy group. I joined friends at the plaza because I thought we would be needed to boost the turnout at a routine demonstration; we anticipated nothing more than a predictable rally and an ordinary march across town to the busy Castro district, where we might ease into the weekend with a couple of drinks at The Detour, a bar popular with boys of the activist set.

Instead, by the end of the night, we had joined hundreds of demonstrators and bystanders and thousands of denizens of the Castro in defying the single worst incident of mass police violence against the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community in the history of San Francisco—an all-out police riot that came to be known as the "Castro Sweep." As the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) ran amok in the city's main queer neighborhood that evening, calls of "Cops go home" and "This is our street" asserted our symbolic claim of ownership. Other chants made the historical precedents clear: "Stonewall was a riot," we shouted, drawing courage from the example of the street queens and barflies who stood up to the police in Greenwich Village in 1969; "Dan White was a cop," we raged, recalling the White Night Riot in San Francisco's Civic Center in 1979 after the queer-hating assassin of Harvey Milk was convicted of manslaughter instead of murder.

AN OCTOBER AFTERNOON

Events had started out mildly enough that October afternoon in 1989. As some 250 protesters gathered on the Federal Building plaza, speeches and street theater put forth ACT UP's demands for action and drew attention to the policy failures of federal, state and local governments. Demonstrators then wrapped the blocky columns at the entrance of the ugly office tower in yards of red tape. A few federal marshals made half-hearted efforts to take down the plastic swaths, but I saw no attempts to confront or restrain the protesters. The whole affair seemed rather low-key on all sides. Around 5 p.m., we moved toward the street for the march; the organizers had scheduled stops for further speeches at nearby San Francisco City Hall and at the United States Mint, located not far from the Castro.

Within moments, the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) unleashed a colossal and incomprehensible show of force. Squads of officers descended en masse to prevent marchers from stepping into the street. A short block from the Federal Building, the first arrest took place: Moving to the curb, I watched two officers strong-arm a shackled man into the rear of a police van. I later learned that this was the ACT UP member serving as police liaison for the protest. He had approached some officers on the street to identify himself and to ask about the massively disproportionate crowd control tactics; they had responded by throwing him to the pavement, hand-cuffing him and carting him off to the Hall of Justice, the cold and cheerless 1960s hulk that houses the city's police headquarters—where he would be joined over the course of the evening by a growing number of fellow protesters.

The marchers pressed ahead and regrouped for the planned rally on the steps of San Francisco's ornate, domed City Hall. Undeterred by the SFPD, we then set out for the Castro neighborhood, some 30 blocks away. The police immediately redoubled their efforts to confine the crowd to the sidewalk, rushing to enforce even the most petty of traffic regulations. When stoplights turned red as we proceeded through crosswalks, wedges of motorcycle cops charged the march, cutting it in two while officers on foot wrenched banners and signs from the hands of protesters. Cops pushed back marchers who strayed from the curb—and in some cases, arrested them. Such tactics were a sharp departure from recent practice in San Francisco, where civil libertarians had pressured the police into allowing peaceful marches without permits to claim a lane in the street and go forward without interruption while officers directed traffic.

Motorcycle batallion of SF Police, Oct. 6, 1989

Photo: Rick Gerharter

San Francisco police line the sidewalk near City Hall to prevent marchers from claiming a lane in the street.

Photo: Brian McNally

The harassment continued along most of the route. Lines of motorcycle cops hemmed in the crowd; squads on foot hounded the marchers every step of the way. From a loudhailer atop a police van, a harsh male voice barked a stream of orders that struck me as at once absurd and frightening in their obsessive repetition: "Stay on the sidewalk" alternating with "Obey the traffic laws." Protesters responded with hearty chants of "Obey the Constitution" and "People with AIDS under attack. What do we do? Act up! Fight Back!" Halfway to the Castro, organizers halted the march under a freeway that crosses a seedy stretch of Market not far from the location where the San Francisco LGBT Community Center would be built more than a dozen years later. An ACT UP representative restated the AIDS-related goals of the protest, asked us to focus our anger and urged us to rebuff the SFPD's efforts at intimidation.

As daylight faded, the march reached the San Francisco Mint, a dark, fortress-like Moderne block that overlooks Market Street from a greenish escarpment at the edge of the Castro. A cold wind was blasting across the open space where we paused for a brief speech about AIDS and the Federal budget. My friend Michael, a 19-year-old new to the city and attending his first ACT UP protest, was wearing only a light sweater and a T-shirt from the anonymous queer cultural activist collective Boy With Arms Akimbo. As I wrapped my arms around Michael to shield him against the cold, he fretted about the cops dogging the march. I assured him that the police would call it a night once we reached the Castro; I was certain the SFPD wouldn't risk the inevitable fall out from a crackdown in the neighborhood internationally recognized as a homosexual homeland. They had dared nothing of the kind since 1979, when four squads—24 officers—had stormed down the street and trashed the Elephant Walk bar at Castro and 18th in retaliation for the White Night protest.

TWILIGHT WAS FALLING

Twilight was falling as we marched down from the Mint and turned up Market Street into the Castro, approaching the planned terminus of the march. A tactical volunteer darted back through the crowd, quietly passing word that we would end the protest by taking over the wide intersection of Market and Castro Streets. A traditional finale for queer demonstrations in San Francisco at the time, this exercise in nonviolent civil disobedience usually involved protesters forming a grand circle in the street to hear short closing speeches and to join in a few rousing chants-after which the crowd would quickly and peacefully disperse. The standard SFPD response to this established ritual: A few officers on motorcycles diverting traffic at the nearest intersections and a few on foot discreetly monitoring the crowd.

A quarter-block from the head of the march, I surmised from the flashing lights of massed SFPD vehicles on Market Street that the scenario would be different this time. Arriving at Casrro Street, I encountered several dozen officers in full riot gear—a horde of blue fatigues, black combat boots, blue helmets with plastic face shields, long black truncheons. I had never before seen so many cops in a single mass. Blocked from the intersection, marchers were surging onto the commercial strip of Castro, filling the street for several yards and preventing the police on Market from moving into the area. Commuters and visitors coming for shopping, dinner or drinks were emerging from the Muni Metro subway station at Harvey Milk Plaza; not far down the other side of the street, the pink and blue art-deco neon of the Castro Theatre towered over the homey two- and three-story buildings that line the block.

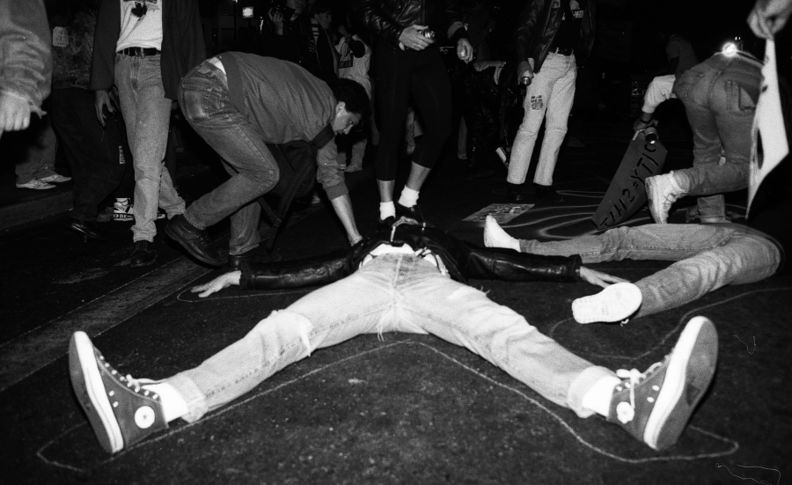

Die-in on Castro before police attack.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

One group of approximately 50 protesters immediately sat down and linked arms in the middle of Castro near Market for an unplanned sit-in. Further down the street, in view of the neighborhood eateries and chichi clothing stores, 20 others staged a die in, sprawling on the asphalt to symbolize the growing death toll of the AIDS epidemic. Like investigators at a murder scene, protesters chalked outlines around the prone bodies. Others then spray-painted the tracings in bright orange, yellow and green, adding stenciled slogans: "One AIDS Death Every 15 Minutes," "Black People Die Faster," "Profits Kill," "Pity Equals Shit." The result was a fluorescent patchwork of anger spilling across the black pavement; protesters instantly declared the display a "permanent AIDS quilt." (The headquarters of the Names Project was just a block away on Market Street; ACT UP members often were critical of the project's political disengagement and excessive sentimentality.)

Sit-in at Castro and Market, Oct. 6, 1989.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

Chanting crowd at sit-in on Castro and Market, Oct. 6, 1989.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/1zyVSfwkILM" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Video: GLBT Historical Society

While approximately 500 people chanted and jeered from the sidewalks on both sides of Castro, the police moved in to arrest the women and men sitting in the street. Finished with this activity, the officers quickly turned their attention on the crowd, which was growing in numbers as passersby stopped to cheer on the activists and to observe—and protest—the massive police presence in the heart of the neighborhood. After a largely inaudible loudhailer order to clear the street, squads of motorcycle and riot police advanced down the center of Castro. Riot cops pushed forward with batons held across their chests, attempting to force people onto the sidewalks. Standing at the curb on the west side of Castro near Harvey Milk Plaza, I could see no escape route; people behind me packed the sidewalk to the shopfronts or were penned in by further police lines at the rear.

The cops soon charged in earnest. I saw one officer advance on the crowd with his baton in a jabbing position, a technique that the San Francisco Police Commission had banned after an officer using it had gravely injured Farm Workers Union co-founder Dolores Huerta at a protest the previous year. Others pushed with the sides of their batons, knocking the front of the crowd off balance. After a partial withdrawal and a second effort to clear the area, the police loudhailer announced that the entire block of Castro from Market to 18th Street—including the sidewalks—was now an unlawful assembly area. The cops plainly were unconcerned about the effect this would have on customers in businesses and on residents in their homes, many of whom had no clue what was going on up to a block away. The crowd near Market held its ground, chanting "Cops out of the Castro" and "Racist, sexist, antigay—SFPD go away." A group at a Muni stop by the Twin Peaks bar threw in a touch of queer sarcasm, chanting, "We're waiting for the bus! We're waiting for the bus!"

A squad of officers soon responded, ramming their motorcycles through the center of the crowd in the street. Standing near the middle of Castro, I was nearly rammed by an officer who turned at the last moment, rolling his motorcycle over my foot. Several officers who had ridden into the crowd proceeded to dismount, leaving their motorcycles unattended in the street. In the confusion, I lost sight of the friends I had been standing with and made my way to the east side of Castro. From that vantage, I watched as officers and members of the public surged up and down the street. In the midst of these movements, I saw one of the abandoned police motorcycles fall over—a result, I presumed, of someone in the crowd inadvertently bumping it. (An employee of a club popular with the women and men of ACT UP later told me that he had in fact kicked the motorcycle—the only report of such an incident from the entire evening.) Apparently in reaction to the motorcycle tipping over, two officers at the SFPD command post near Market Street broke ranks and ran into the crowd; the second of the two charged a man standing quietly in the street and clubbed him over the shoulder. Shortly thereafter, I saw another officer back a cringing bystander into a newsbox at the corner of Castro and 17th Streets, then beat him to the sidewalk using an overhead baton swing. The officer swung again after the man fell to the ground. Other cops joined in, one of them so eager to land a blow that he clubbed a fellow officer. And I watched in horror as a cop crouched slightly and leveled a bazooka-like weapon from a distance of five feet at the face of a passerby; for a moment, I feared the worst, then the man fled to safety. I subsequently learned that the gun was a "bean-bag launcher," used to shoot rubber bullets, tear-gas canisters and other putatively non lethal ammunition.

Cops sweep down Castro Street, Oct. 6, 1989.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

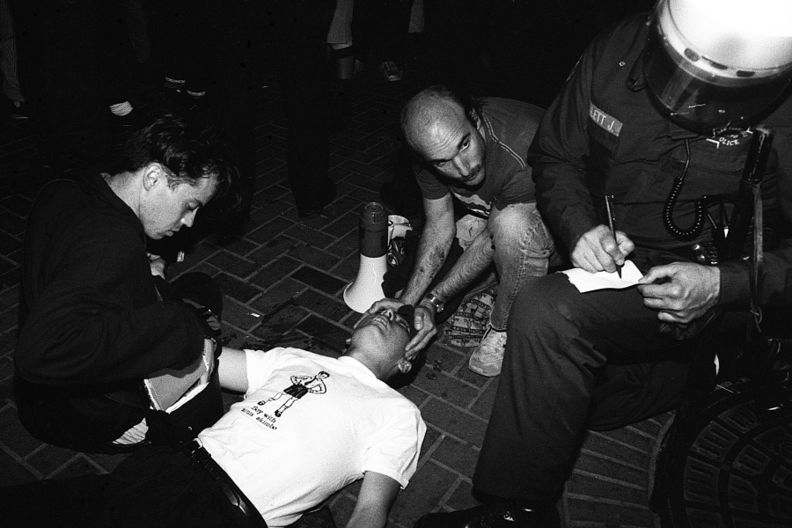

Injured man down, Oct. 6, 1989.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

Minutes later, I heard someone calling out my name and spotted a friend leaning from an ambulance moving through the police lines. "I'm going to the hospital with Mike," he shouted. With a sinking feeling, I pushed my way to the small back window; in the cold white light, I could see my friend Michael strapped motionless on a stretcher. Michael received several stitches to close a gash across his eyebrow. According to witnesses, Capt. Richard Cairns, at the time head of the SFPD tactical unit and commander during the Castro Sweep—whom activists soon dubbed "The bully of the Castro Sweep"—had moved down the gutter at Harvey Milk Plaza, striking several protesters with his baton before reaching the point where Michael stood. He then clubbed Michael in the face, knocking him to the brick sidewalk and leaving him bloodied and semi conscious. From the opposite corner, I had heard protesters chanting the officer's helmet number, but had not seen the beating. I later determined that he was the first of the two officers I had seen charging from the police command post.

Around 9 p.m., the enormous mass of cops formed into a phalanx extending the full width of the street and sidewalks where Castro meets Market and 17th. Advancing in lockstep, billy clubs at the ready, they commenced systematically sweeping protesters and passersby down the block toward 18th Street. The SFPD clearly was determined to leave no doubt about who controlled the Castro: The famed haven for queers was merely provisional; it vanished at the stroke of a baton. Left behind the line of the sweep, I moved with several strangers onto 17th Street, taking refuge in the entrance of Orphan Andy's, an all-night diner. Officers approached us there and told us that the entire neighborhood was now an unlawful assembly; anyone out-of-doors was subject to arrest. An employee of the diner immediately pulled me inside; at the same time, the cops were insisting that the management did not want us to enter. Exhausted, disoriented, separated from my friends-but still clutching a notebook in which I had scrawled the helmet numbers of offending officers-I retreated home as soon as the police moved further down 17th Street.

EMPTYING THE STREETS

In the months after the sweep, I learned that the officers' threat to clear the sidewalks and streets throughout the Castro had not been hyperbole. From witnesses, from photographs, from videotapes shot by two queer journalists, and from the SFPD's own videotape and documents, I pieced together the extent of the invasion. Accompanied by further police beatings and arrests, the sweep had completely emptied almost seven blocks of the Castro, including the entire commercial center of the neighborhood on a bustling Friday night. Officers had ordered everyone in businesses and homes along the extent of the sweep to remain indoors, in effect placing thousands under house arrest for nearly an hour. (With mordant humor, one acquaintance later told me about his worst experience of the evening: The cops marching down Castro had forced him to stay inside a bar playing dance music so cheesy that he was driven to desperation.) Through the sweep, a persistent band of protesters had dodged ahead of the police, refusing to abandon the street to the SFPD. When the officers finally withdrew from the neighborhood around 10 p.m., the group formed a circle in the intersection of Castro and 18th, sent up a cheer, then dispersed—the very wrap-up that would have come hours before and a block away if not for the grotesque overreaction of the SFPD. The extent of that overreaction became even clearer after the fact as police brass tried to justify the sweep. Then-chief Frank Jordan, who did his ineffectual utmost to minimize his officers' misconduct, was forced to admit that half of all the cops on duty the evening of October 6, 1989, had invaded the Castro. The department's actions had been so chaotic that neither the SFPD nor the Office of Citizen Complaints (OCC), San Francisco's civilian review agency, ever managed to determine the exact count, but the total approached 200—nearly ten times the number that had attacked the Elephant Walk a decade earlier.

SFPD officers mass on Castro Street near Harvey Milk Plaza around 8:15 p.m. on Oct. 6, 1989, after arresting sit-in protestors and before violently sweeping the neighborhood. (One of only two known color photos of the Castro Sweep; taken by a work colleague of ACT UP member Bob Smith)

The question that many in the Castro were raising as the sweep went forward and that the media, the city's liberal political establishment, and a wide range of San Franciscans took up the next day was simple to ask, yet difficult to answer: Why? The SFPD's spectacularly ill-advised adoption of a belligerent zero-tolerance policy in response to a small, peaceful and quite routine AIDS demonstration seemed utterly baffling. Suggestive but not fully conclusive evidence gradually emerged in news stories, Police Commission and Board of Supervisors meetings, OCC investigations, police misconduct hearings, and two lawsuits filed against the city—a civic turmoil that persisted for three years. As an activist outraged by the Castro Sweep, I took an active role in many of these proceedings, including filing a formal OCC complaint, which enabled me to read the agency's otherwise confidential investigative reports.

We eventually learned that SFPD Assistant Chief Jack Jordan—the brother of Chief Frank Jordan—had written an operations plan for October 6, 1989, that called for a total of 24 officers to facilitate the ACT UP march in the customary manner. This plan was subsequently torn up without Jack Jordan's approval at a meeting called by one of his immediate underlings, Deputy Chief Frank Reed, a cop regarded by many progressive organizers in San Francisco as an authoritarian deeply opposed to the city's tradition of street protest. Reed directed the commanders assigned to the demonstration to confine the march to the sidewalk, whatever the cost. And he authorized them to deploy as many officers as needed—to "strip the station houses" if necessary, as one meeting participant told the OCC. Questioned by the agency's investigators, the officer declined to explain why he overturned the original plan and tried to dodge responsibility for the decision.

In the year before the sweep, AIDS activists in San Francisco had staged a number of high-profile protests, including the first-ever sit-in on the Golden Gate Bridge, which completely blocked traffic on the span at morning rush hour, and a colorful demonstration that disrupted the socialite-packed opening night of the San Francisco Opera. Given the SFPD's long history of ambivalence and at times outright hostility both to homosexuals and to protesters, many activists concluded that the crackdown on October 6th was an act of retaliation by a substantial faction of the department that was fed up with the antics of radical queers and with the liberal establishment that tolerated them. The police riot that ensued in the Castro was seen as a symptom of broader homophobia among cops unable to imagine that ACT UP members posed no threat to public safety or private property in a gay neighborhood-and unconcerned about the real and symbolic harm that pitilessly suppressing this nonexistent threat would cause.

Lone protester sits in front of advancing police, Oct. 6, 1989.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

Another protester braves the armored troops.

Photo: Rick Gerharter

In addition to this broad retaliation, a small number of ACT UP members in the days immediately following the sweep told me that they believed a narrower desire among specific officers out for revenge was a key to understanding the motivations of the police. According to this account, 50 to 100 AIDS activists holding a political funeral for Terry Sutton, a leading member of ACT UP/San Francisco in its early years, had marched down Castro without a permit late on the afternoon of April 28, 1989. A small group of SFPD officers sent to police the event had confronted the marchers; filled with grief and anger over Sutton's death, the protesters had turned on the cops and chased them out of the neighborhood. ACT UP held no further street protests in the Castro until the October 6th event six months later. The evening of the sweep was therefore the first chance for the cops to show the uppity queers that the SFPD retained ultimate control over the use and meaning of public space in the neighborhood.

I frankly regarded this explanation with skepticism: AIDS militants expelling the cops from the most famous gay neighborhood in the world sounded too much like the stuff of radical folklore. I nonetheless filed a public records request for SFPD documents on the Sutton protest and tracked down a videotape shot by Electric City, a local gay cable access program. To my surprise, this evidence corroborated the activists' account, suggesting that revenge might indeed have been one element in the Castro Sweep. In a less than grammatically correct SFPD memo, Capt. Robert Fife, the tactical officer at the Sutton protest reported that he had feared "the platoon would be out flanked" and had withdrawn the officers from the scene due to concern that the crowd "might of become hostile." I could identify only a few officers from the April event, but police records showed that the majority of them were back in the Castro for October 6th. Most telling of all, the SFPD officer in command for the Sutton demonstration was the very cop who turned up again as event commander for the Castro Sweep.

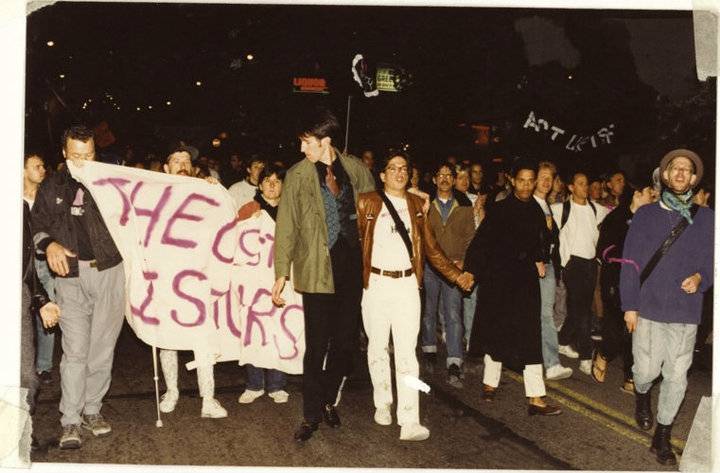

RECLAIMING THE CASTRO

If the SFPD's crackdown was designed to silence AIDS activists and to reimpose police power in the public space of the Castro, the effort backfired spectacularly. Through word of mouth, through a "truth wall" posted on the Elephant Walk bar, through broadcast media coverage (much of it skewed against the activists, yet easy enough to decipher), through an ACT UP flyer distributed widely the next morning, news of the police riot spread immediately—with disbelief, shock and outrage in its wake. The evening of October 7, 1989, brought some 2,000 people to the Castro for a protest against the attack. I attended with friends, accompanying the now bandaged and apprehensive Michael. Queers, people with AIDS and our allies from across San Francisco surged from Harvey Milk Plaza to parade through the neighborhood for three hours, reclaiming the streets from the cops, who kept a studiously low profile. Two young men—one Asian, one white—carried a butcher-paper sign with block-lettered words: "The SFPD Has Blood on Its Hands (Again)." And near the head of the march, a banner made from a bedsheet summed up the sentiments of many: "The Castro Is Ours."

Oct. 7, 1989: A march reclaims the Castro for queers the night after the police invasion of the neighborhood. The slogan on the bedsheet banner at left reads “The Castro Is Ours.” The ACT UP/SF banner is visible at upper right.

Photo: Courtesy of Brian McNally.

A series of cultural and political actions in response to the sweep demonstrated the ongoing desire of many San Francisco queers to reassert their ownership of the Castro as a public forum. An early example came a little over three weeks after the police riot: Appropriating the Halloween street party that brings tens of thousands of people to the neighborhood, Boy With Arms Akimbo debuted a poster series titled "Continuity of Courage: 69/79/89,"which used photos and graphic variations on the numerals for the years to draw parallels between Stonewall, White Night and the Castro Sweep. Multiple copies appeared on hoardings, newsboxes, and light poles throughout the district. Supportive merchants gave window space, and the management of the Castro Theater provided the large poster cases at the famed movie palace (closed at the time due to damage from the Lorna Prieta earthquake, which occurred 11 days after the sweep). Akimbo followed up six months later by inviting discussion about the sweep with a site installation at A Different Light Bookstore on Castro Street.

San Francisco activists also created a distinctive form of demonstration in reaction to the sweep: "permit-free street parties" where the crowd closed Castro for a combination of protest and festivity without the permits required by the SFPD. The first such event, organized by ACT UP/San Francisco, took place in late June 1990, when thousands from across the country arrived for protests at the Sixth International AIDS Conference and tens of thousands more came for the annual Pride Parade. On the evening before the parade, ACT UP led the revelers in the Castro from the sidewalks into the intersection of 18th and Castro Streets, launching an evening-long street party—and giving birth to the "Pink Saturday" celebration that has become an official event during San Francisco's Pride weekend. Similarly, for three years after the Castro Sweep, an ad hoc group known as "Bad Cop/No Donut" marked the anniversary with illegal street festivals that brought together political speakers and go-go dancers, protest signs and party decorations-all to demand justice for victims of the police riot.

From the perspective of the present, the Castro Sweep may seem like part of a vanished era. A number of the activists at the center of the struggle died before their time, killed by the disease that had brought them into the streets to protest that day in 1989. The militant AIDS movement declined throughout the 1990s, with ACT UP/San Francisco itself disbanding around 1994 {its name now has been appropriated by a cadre of HIV denialists who contradict virtually all the beliefs of the original group). At the same time, many concerns raised by the sweep have not disappeared. No solution is in sight for the global AIDS crisis. In San Francisco, many of the cops who ordered and executed the outrages of October 6, 1989, are on the force to this day, still wielding their blood-stained truncheons, their bitter memories, their political resentments.

And the Castro itself remains a contested territory: a symbol of queer self-determination where few of us now can afford to live, a challenging home for small shop keepers and a tempting plum for corporate profiteers, a familiar space for local gatherings and a rainbow-flag-waving destination for tourists. Today, when I take the 15-minute stroll from my home in the Mission District to the Castro to see a film, get a haircut or check my post-office box, I find myself in a neighborhood that is both oddly comforting and deeply problematic. But I can't convince·myself that the power structure of the SFPD understands or cares about such complexities. Should queers again take to the streets in times of trouble, I have little doubt where we will go to make our voices heard-and no doubt at all where the cops will go to insist that we behave by their rules.

NOTE: In preparing this account, I have drawn not only on my current recollection of the Castro Sweep, but also on two texts I wrote shortly after the event: "San Francisco Journal: Stonewall for a New Generation," published in the New York City queer newsmagazine Outweek (November 5, 1989), as well as the formal narrative I included in the police misconduct complaint I filed with the San Francisco Office of Citizen Complaints on December 1, 1989. I also reviewed documents in my personal archives, including images kindly supplied by San Francisco photojournalists Jane Philomen Cleland, Marc Geller and Rick Gerharter. I am grateful to David Mueller and Bob Smith for their comments on my first draft. This essay is dedicated to the spirited organizers of the original ACT up/San Francisco and to the memory of all those we have lost to AIDS.