Naming of Haight Street, Part 4: The Last Haight Standing

Historical Essay

by Angus MacFarlane

The Panhandle in 1882. Baker and Oak Streets at front right corner of park, dunes still predominant in area. Upper Haight Street would be in the foreground, beneath this image, but largely undeveloped.

Photo: Private collector, San Francisco, CA

To an Argonaut arriving in San Francisco in 1850, the chaotic boomtown’s social fabric must have seemed to have completely unraveled. In truth, the instant city of San Francisco never had time to weave a social fabric. Prior to the discovery of gold, Yerba Buena was a sleepy settlement of a few hundred people scattered around a cove living relatively simple, untroubled lives. As tens of thousands of 49ers descended on the cove, San Francisco became a Darwinian free for all where altruistic urges were incompatible with the lust for wealth.

Perhaps the first person to seriously consider California’s future needs was General Mariano Vallejo. The Alta of April 10, 1850 published the General’s offer to the yet-to-be state of California of 156 acres of land and $370,000 to establish a permanent capitol on his property at the Carquinez Straight. With amazing foresight, Vallejo offered land and money not just for the obligatory government buildings, but for institutions and facilities to aid and to better Californians such as 20 acres and $20,000 for a state university; the same for a state penitentiary; also a state lunatic asylum; and the same for a state orphan asylum. (For reference, 20 acres is six square Sunset District blocks.) Despite publishing his offer in the Sacramento Transcript every day from May 7, 1850 to December 30, 1850 nothing came of it.

On December 29, 1850, the day before the final printing of Vallejo’s offer, the steamship Northerner docked in San Francisco. According to the Alta, a Mr. Baker died of Chagres fever on December 21 and his wife died on December 23, leaving their two children to complete the final week of the Panama-to-San Francisco voyage as orphans. The Sacramento Transcript tallied four orphaned Baker children. The San Francisco Daily Courier reported that the Bakers left four parentless children and that a second couple had died en route, bringing six orphans to San Francisco. (32)

The Courier concluded:

This is truly a sad and melancholy affliction to these little ones, who are cast upon our shores parentless and helpless. They are entitled to the aid and sympathy of our people. We hope that measures will be taken at once to provide for their relief. It becomes our people to see to these little children, and provide them homes.

In the East Coast cities it was often “society ladies” who provided very primitive social services. Deterred from working by Victorian-era conventions, upper class women often assumed the burden of helping the needy at a time when there were no publically funded agencies, organizations or institutions. With their abundant energy, free time, intelligence, social contacts and Christian virtues, these wives of well-to-do husbands, through their goodwill organizations known as “charities,” were a lighted candle in the otherwise dark world of society’s unfortunates.

That philosophy, transplanted to San Francisco, mobilized a group of sympathetic ladies to aid the orphans cast upon their shores. (33) Led by Elizabeth Waller, San Francisco’s original do-gooders formed the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum (POA) on January 31, 1851, the first social service agency in California. (34) On March 21 the first nine orphans, five girls and four boys ranging in age from three- to twelve-years old, moved into a donated house. (35)

Seeing a permanent need to aid San Francisco’s growing number of parentless and abandoned children, the ladies placed newspaper ads in September:

WANTED: A lot for the Orphan Asylum. The ladies of the San Francisco Orphan Asylum wish to purchase a 100-vara lot in the suburbs of the city on which to erect a permanent asylum.

(A “vara” was a commonly used Spanish unit of measurement of roughly one yard.)

On December 6, 1852, Weltha Haight, wife of banker Henry W. Haight, arrived in San Francisco with her three-year-old daughter Minnie. Coincidentally, they arrived on the Northerner, the same steamship which brought the orphans to San Francisco two years earlier. (36)

About that same time, San Francisco’s Mayor Cornelius Garrison encouraged the POA to bid on two blocks of city-owned land in the undeveloped and unpopulated area west of Larkin Street area that would be auctioned on February 28, 1853. (37) At a time in San Francisco’s history when private deeds were suspect, city property carried assurances of accurate title, which significantly increased the value of the land. Thus, auctions of city property was blood in the water for opportunistic land sharks, creating bidding frenzies. However, when it became known that the POA was interested in this particular property, the rapacious speculators graciously allowed them to buy the land for $100. (38)

Once the POA had the land for their permanent orphanage, a building committee was formed on March 3, 1853, which included Elizabeth Waller.(39) Weltha became a POA member at the same meeting, being elected to the Board of Managers (Board of Directors). (40)

Two weeks later ads for architects appeared in the papers:

ORPHAN ASYLUM—Architects and others are solicited by the San Francisco Orphan Asylum Society to furnish plans for a building of stone or brick to be erected on the heights, Old Mission Road, near the Mission Dolores, for the comfortable accommodation of five hundred children, male and female, the Matron and her assistants. The society contemplates erecting, at present, but a portion of the building, say for the accommodation of one hundred children.

On May 5 Weltha was appointed to fill a vacancy on the building committee. (41)

While stone was being quarried at Mint Hill and hauled 200 yards to the construction site, Weltha was active in the founding of another charity. On July 12, 1853 the San Francisco Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society was formed. Their stated mission was “to render protection, aid, and information to women in distress or need—residents or strangers.” For the first year Weltha was the society’s treasurer, donating her time and energy to two worthy causes. (42)

On March 22, 1854, the $30,000 orphan asylum became the new home for fourteen boys and nine girls. Other residents included a matron, her husband and children, a nurse and a teacher.

On May 1, 1854 Weltha gave birth to her second child, Flora. (43)

At the beginning of the Ladies’ Relief Society’s second year, July 12, 1854, Weltha was elected to the society’s Board of Managers. At the same meeting the minutes note:

Through Mrs. Haight, the generous offer of a lot on Folsom Street for the nominal sum of $1.00 per year for as many years as the Society occupy it as a “Home for the Destitute” was received from Mr. Henry Haight. (44)

That was the last reference to Weltha in the Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society’s minutes. Founded on Yerba Buena Cove, San Francisco could only grow westward. Between William Richardson’s 1835 rough sketch of Yerba Buena to William Eddy’s 1849 survey of San Francisco, the city’s cartographic western boundary moved inexorably toward the Pacific Ocean: San Francisco’s own Manifest Destiny. Although labeled as “original and authentic” or “official”, O’Farrell’s 1847 map and Eddy’s 1849 map had no basis in defining San Francisco’s legal boundaries since the city was not a legal entity till the Charter of 1850.

San Francisco’s first legal boundary, the Charter Line of 1850, set the western city limits at approximately today’s Webster Street. The City Charter of 1851 moved the Charter Line to near Divisadero Street. Before the 1856 Consolidation Act, everything beyond the Charter Line was San Francisco County.

The maps of the day showed that the two blocks owned by the POA were bounded by Middleton, Sanders, Wright, and Halleck Streets, and bisected by Beverley Street. Surrounded by sand and scrub, the streets existed only on the maps. It would be years before Market Street penetrated the sand hills that far west, and even longer before other streets were laid out. The nearest landmarks were Mission Dolores, ½ mile to the south, and Yerba Buena Cemetery, 0.8 mile to the northeast. A short distance to the west of the orphanage was the old Mission Dolores-Presidio Trail from Spanish days.

In September, 1854 Weltha’s husband, banker Henry W. Haight, running as a Whig candidate, was elected to the Board of Assistant Aldermen of the City Council. His term in office lasted less than 10 months when an election under the Charter of 1855 brought in a new slate of councilmen in July 1855.

The city took no official interest in its western addition until April 2, 1855 when Alderman James Van Ness submitted an ordinance stating “The City shall relinquish all her rights and claims to (that part of the city West of Larkin Street and southwest of 9th Street) in favor of the present possessors, being resident citizens of San Francisco, with the exception of reserves for public buildings, etc.”

The Van Ness Ordinance was a controversial capitulation to the squatters in the Western Addition, but it also took into consideration the honest people who bought land beyond Larkin Street and 9th Street believing that the titles were clear, which often turned out to be otherwise. Rather than engage the squatters or faulty-deed holders in costly, lengthy, and uncertain ejectment suits, the city gave away the land in exchange for a clean slate.

One of the provisions of the Van Ness Ordinance was: “The City will proceed to lay out and open streets as the [City] may deem it expedient in that part of the city west of Larkin Street and southwest of [9th] Street.”

On March 23, 1854 the Alta acknowledged receipt of a large map of the city from publisher M. Bixby, Esq. “compiled from the best and most recent surveys and embracing the Western Addition and the Mission Dolores.” Reproduced from the records and surveys of R. P. Bridgens, Civil Engineer, this map was an enormously large and lavishly embellished reproduction of the Dexter Map of 1851, and presumably Marlette’s 1850 map. Unlike Dexter’s map, this map only went as far west as the western-most street: Cannon Street. (45)

Although these West-of-Larkin-Street maps never received the imprimatur from the City as being “official”, they became the consensus maps of San Francisco. As late as June 1, 1855, the City Council was referring to West of Larkin streets by the names on these maps for tax purposes. Real estate ads used the maps’ street names into 1857. The city directories listed the streets as they appeared on these maps through 1858.

On November 12, 1855 the City Council named Horace Hawes, Michael Hayes and Charles Gough to “lay off the streets in the Western Addition of the city under the provisions of the Van Ness Land Ordinance”. They submitted their report and recommendations to the City Council on April 21, 1856, which began:

Your Commissioners, after a patient and thorough examination of the land, have adopted the accompanying plan or map thereof, showing the streets so laid out, and the lots and squares selected for public purposes and recommend its adoption as the official map of the portion of the city [West of Larkin and southwest of 9th Street.]

Unfortunately, the Commission’s plan or map suffered the same fate as Marlette’s map. It’s not known when the recommendations “showing the streets so laid out” were implemented, but only four street names from the pre-1856 survey survived into the new era: Webster, Laguna, Haight and Hays. Three of the old names were moved: Webster Street was relocated five blocks to the west; Laguna was shifted 1½ blocks westward; and Haight Street found a new home one block south. Hays Street remained in place, but gained a vowel to become Hayes Street.

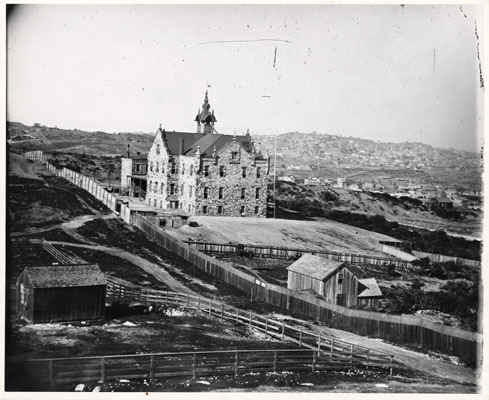

1860s view of San Francisco Orphan Asylum Society, bounded by today's Haight, Buchanan, Hermann and Laguna Streets, where the UC Berkeley Extension operated until mid 2000s.

The Protestant Orphan Asylum, originally bounded by Middleton, Sanders, Wright and Halleck Streets, now found itself defined by Haight, Buchanan, Herman and Laguna and bisected by Waller. It’s not known how or why or even when the myth of this new Haight Street being named for banker Henry Welles Haight originated. (46) The believers of the myth assert, without any proof, that it is because he donated the land for the orphanage. There is nothing in the historical record to support this, although in 1854, after the Protestant Orphan Asylum had been built, Henry Haight did offer the San Francisco Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society a lot on Folsom Street for $1.00 per year for a “Home for the Destitute.” (47)

The only explanation for the naming of Haight Street is found in a small pamphlet at the Bancroft Library of the University of California written by Mrs. W.A. Haight dated May 1, 1900 titled: Some Reminiscences of the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum.

Having been involved with the POA for 47 years, Weltha had been frequently asked to share her personal experiences and recollections with the newer members. With this sixteen-page pamphlet she obliged.

On pages three and four Weltha recalls:

Very early in 1853, our numbers having increased rapidly, it became evident to us that we must, if possible, secure a home of our own, and steps were taken to bring about that end. The Mayor of our city, Captain C. K. Garrison, was much interested in our work, and promised his aid in every way, and looking about for a suitable location, discovered several blocks belonging to the city, which he caused to be offered at public auction, at the same time informing our Trustees that they could bid on the property, and by paying a small sum to the squatters who were occupying it, the Orphan Asylum could become the owner. This was done, and only $100 was paid for twelve fifty-vara lots, two entire blocks.

There is no mention of the land being donated. She continues on page five:

Before any steps could be taken toward building, however, it was necessary that that portion of the city should be surveyed and the streets be marked off, so that a proper site for the building could be selected. My husband, being a member of the Board of Supervisors, soon had this accomplished . . .

Tidying up Weltha’s recollections a bit (after all, she was 75 years old when she wrote the pamphlet recalling events nearly half a century earlier), she can be forgiven her lapse in referring to her husband as being a member of the Board of Supervisors when he had in fact been an Assistant Alderman. (From 1856 on, the legislative branch of the city’s government was indeed called the Board of Supervisors.)

Or that he was no longer a board member when the survey was conducted. (Henry died in 1868, so he wasn’t a resource Weltha could use.)

The “survey” of that portion of the city where the orphanage was to be built was, of course, the Van Ness Ordinance of 1855, which was introduced while Henry was in office, but was not completed till the following year when he was no longer an Assistant Alderman. Plus, the orphanage had already been built when the survey was undertaken.

Again, forty-five years later Weltha can be forgiven these insignificant lapses. On page five she modestly notes:

. . . and out of compliment to two of the Managers [of the Protestant Orphan Asylum], Waller Street and Haight Street were named.

Certainly there was public discussion, maybe even debate, on whom to honor with the new West-of- Larkin-Street street names. Henry undoubtedly used his personal influence with the incumbents on the Board of Supervisors to rename Middleton Street Haight Street to honor his wife, and Waller Street to replace the former Beverley Street in recognition of Elizabeth Waller, one of the founders of the Protestant Orphan Asylum. (48)

Haight Street stood as the Protestant Orphan Asylum’s northern boundary and Waller Street as the southern boundary till 1919 when the 65-year-old building became too much of a maintenance problem and the children were moved to another orphanage in the Richmond District. The property was eventually sold to the State of California.

Almost immediately upon her arrival in San Francisco in 1852, Weltha embraced the spirit of the Daily Courier’s 1850 plea to help “the little ones cast upon our shores”. For the next 53 years she continued to embrace the little ones “[who] are entitled to the aid and sympathy of our people . . . to see to these little children and provide them homes”.

Weltha’s passing on February 7, 1906 was the day after the 56th annual celebration of the founding of the Protestant Orphan Asylum. Sadly, history has completely forgotten her lifelong dedication to California’s first social service organization, and has chosen instead to honor her husband for something he never did.

Samuel Haight died on February 27, 1856 at the age of 33, two months before the West of Larkin survey was completed. He never knew that Haight Street would be renamed for his sister-in-law, but he would have been delighted.

Notes:

32. Daily Alta California, December 30, 1850, page 2, column 3:“Arrival of the Steamship Northerner”; Sacramento Transcript, December 31, 1850, page 2 column 6: “Melancholy”; San Francisco Daily Courier, December, 30, 1850, page 2 column 1, “Melancholy”. Rasmussen, Page 88, mentions a Mr. & Mrs. Smith as dying en route, but no mention is made of any orphaned Smith children.

33. Daily Alta California, January 28, 1851, page 2, column 3: Association for the Care of Orphans: The growth of our city has brought within its limits all the usual variety of social condition found in large communities in other lands. It is a cause of wonder that hitherto the distinctions of rich and poor, the independent and the helpless, have been to a great extent unknown. Such a favorable state of things could not, however, be expected long to continue. Already a demand for organized, systematic methods of charity exists; and among the objects calling for friendly aid and benevolent care, are not a few left in a state of infantile orphanage, thrown by the hand of Providence upon the attentions of a benevolent public. Measures, however, to meet this demand, we are happy to say are in progress; and the better to promote the end in view, the ladies of this city will hold a meeting in the Presbyterian Church, Stockton street, next Saturday [February 2] at two o’clock PM, at which time the plan of an Association for the Care of Orphans will be resented.

34. Constitution, By Laws and Minutes of the Proceedings of the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Society, book 1, page 37. From the Edgewood/San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum Collection Box 4 folder 1 at San Francisco History Center. (POA Minutes.)

35. None of these children were the orphans from the Northerner. According to the POA Minutes (page 47), they were all “half orphans,” i.e. they had only one parent. Their surnames were Dodds (two boys, two girls) Ward (two girls, one boy) and Plumbridge (one boy, one girl).

36. RASMUSSEN, Louis J. VOL. 4 SF Ship Passenger Lists Pages 202, 204, San Francisco Historic Records, Colma, 1970.

37. Haight, Mrs. W.A., Some Reminiscences of the San Francisco Protestant Orphan Asylum; 1900, self-published. Bancroft Library; Bancroft Call Number: F869 S3 .5 S161; pages 3, 4.

38. Daily Alta California, Jan. 25, 1878, page 2, column 2; Call, April 12, 1901, page 5, column 4.

39. POA Minutes, page70.

40. POA Minutes, page 69.

41. POA Minutes, page 73.

42. Ladies’ Protection and Relief Society, Proceedings of the Board of Managers, Page 5, July 12, 1853. California Historical Society, Call Number MS 3576 vol. 1 1853-1857.

43. Dwight, PAGE 670. Weltha and Henry Haight had four children: Minnie (born October 23, 1849); Flora May (May 1, 1854); Franklin Henry (June 26, 1858); Frederick Billings (June 1, 1861).

44. Ladies’ Minutes, July 12, 1854, unnumbered page.

45. A very distressed copy of this map can be seen in the 6th floor elevator lobby at San Francisco’s main public library.

46. Although not referring to Henry W. Haight, perhaps the earliest misattribution might be San Francisco Call, September 8, 1901, page 5, magazine section. HAIGHT STREET—After Henry H. Haight, a native of New York, lawyer by profession and Governor of California from 1868 to 1872.

47. There are no records of Henry W. Haight offering land or money to the POA for an orphanage. The POA minutes note on May 6, 1852 (page 60) that Col. Jonathan Stevenson had offered the POA a lot. The first two temporary homes were donated by W. D. M Howard (a pioneer San Franciscan) and Henry Halleck of the law firm of Peachy, Billings & Halleck.

48. Just as Waller Street parallels Haight Street, there is a parallel myth that Waller Street was named after Royal Waller, Elizabeth’s husband. One reason given is that he “basically founded the orphanage.” As with Henry Haight, there is not a shred of historical evidence to support that myth.