Mel’s Drive-In Protest 1963

Historical Essay

by R.J. Moore, 2021

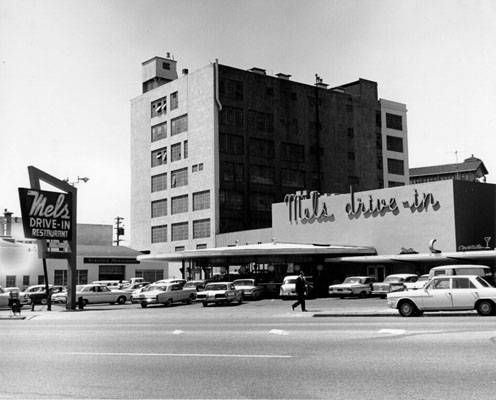

Mel's Drive-in at 3355 Geary Blvd. at Beaumont, early 1960s.

Photo: courtesy San Francisco State University collection

| Entering the 1960s, African Americans living in San Francisco continued to face significant discrimination in the area of employment, often excluded from occupations that interacted with the public, with few businesses open to hiring minorities in general. During the early years of the decade, however, the city entered a new wave of political upheaval as community members, activists, and organizations sought to secure equal employment opportunities for African Americans and other minority populations living in San Francisco. The 1963 protest at Mel’s Drive-in in response to racist hiring practices soon helped define the city’s reckoning of race-based employment discrimination amidst additional fights during the Civil Rights period, paving the way for additional demonstrations and greater change for the city’s African American residents. |

By the 1960s, San Francisco’s widespread racist employment patterns ushered in a series of social protest movements led by the city’s progressives aimed at promoting equal rights and job opportunities for African American residents of the city. The Civil Rights Movement was expanding northward after major protests in the American South where most of the African American population was concentrated at the time. African Americans were a minority in San Francisco, but racism limited job opportunities and had been prompted the creation in 1958 of a largely ineffective municipal Fair Employment Practices Committee. Among the local businesses in the Bay Area targeted for their discriminatory hiring practices was Mel’s Drive-In, a restaurant chain with locations in San Francisco and Berkeley co-owned by Mel Weiss and City Supervisor Harold Dobbs. The sit-in at Mel’s Drive-In garnered a large number of participants, from local college students to community activists, and became the first mass sit-in of the Bay Area Civil Rights Movement.(1)

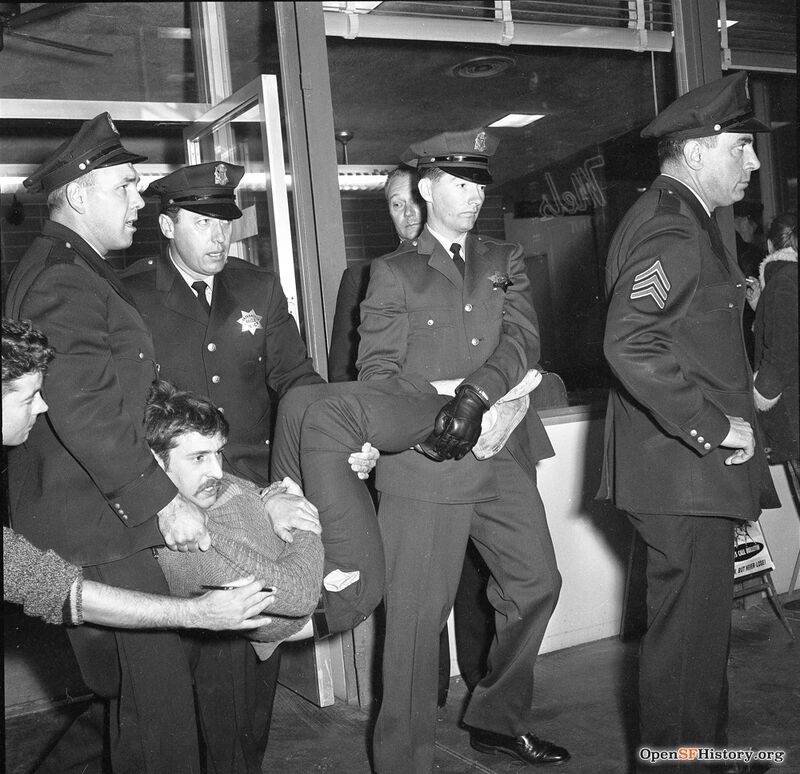

Police arrest protesters engaged in passive resistance, November 3, 1963, at Mel's Drive-in restaurant on Geary Blvd.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp28.3202

Another arrest at Mel's Drive-In.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org wnp28.3194

What prompted the picketing demonstration was an investigation into the hiring practices of the restaurant chain conducted by the Direct Action Group, started by Art Sheridan, at the time a student of San Francisco State College. The probe found that Black employees of Mel’s Drive-in were relegated only to behind-the-scenes jobs, such as kitchen positions. DAG chairman Sheridan once stated that African Americans workers of the establishment were, “always out of sight. They’re janitors, dishwashers, and people like that.”(2) Essentially, Mel’s Drive-In did not employ African Americans in any position which required the worker to come into direct contact with patrons.(3) The Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination in particular began organizing the picketing campaign against the franchise, becoming nominally in charge of the demonstration.(4) An umbrella organization, the Ad Hoc Committee was made up of a loose collection of civil rights organizations, both formal and informal, nationally recognized and locally grassroot, who together acted as a unified front in the interests of the Ad Hoc Committee to fight against racial forms of discrimination. According to former leader of the Ad Hoc Committee Tracy Sims, now known as Tamam Tracy Moncur, “it was a combination of the W.E.B. DuBois Club, students from Berkeley, and the NAACP… [which had actually]... started at Mel’s Drive-In”.(5)

The picketing campaign began in October 1963 at several chain locations in San Francisco and across the Bay. Recruitment for the picketing campaign, and subsequent sit-in, at one point occurred in the Fillmore District, with organizers announcing plans to picket with a loudspeaker.(6) On November 2, protests began outside of co-owner Harold Dobbs’ residence. The next day, November 3, protestors once more picketed Mel’s Drive-In on Geary Boulevard, this time performing a mass sit-in in which every single empty booths and stool in the restaurant was filled by a protester. The protest continued through the weekend. San Francisco police arrested sixty-four demonstrators on Saturday night, and an additional forty-eight on Sunday.(7) Participants of the sit-in utilized familiar nonviolent civil disobedience strategies until they were forcibly removed by local police.

Mel's Drive-in protest, Nov. 3, 1963.

Photo: OpenSFHistory.org, wnp28.3189 / Fred Pardini, SF Examiner collection

The picketing campaign and sit-in demonstration occurred mere days before the city mayoral election in which co-owner Harold Dobbs was running, projected to be the leading candidate. Of the plans to picket the establishment, Dobbs believed they were a “politically contrived” plan devised by students of San Francisco State College to get his opponent, Democrat John F. Shelley, into the seat of the mayor.(8) Members of the Ad Hoc Committee, however, denied this, even putting the protest at a pause to let the election go by. The demonstrations placed the mayoral election at the last minute into a juncture at which the issue of race, which hitherto had not been discussed between the candidates, could not be ignored, as “what the movement recognized was the opportunity to thrust the issue of race and employment into the political mix as the election neared.”(9) Shelley used the ongoing demonstrations to his political advantage when he reaffirmed his support for the basic constitutional right of legal protest. Dobbs lost the election to Shelley, a rippling effect of the demonstrations which had inarguably swayed the election in Shelley’s favor.

Mel’s management and the Ad Hoc Committee eventually began a negotiation process on November 6. Two days later, on November 8, Dobbs and restaurant management reached an employment agreement with the Ad Hoc Committee. The agreement, proclaimed over loudspeaker to a group of demonstrators, outlined the assurance of brand new, nondiscriminatory hiring practices for the chain; plans for the establishment of a training school for African American employees; and included provisions that all Mel’s restaurants would allow African American employees to occupy up-front positions such as waitresses, cashiers, and bartenders.

The provisions of the agreement were together considered a victory and concluded the wave of demonstrations which had taken place at Bay Area Mel’s Drive-Ins.

The sit-in at Mel’s Drive-In is considered a seminal event; it ushered in a re-energized movement in San Francisco to fight racial economic inequalities. Following the success of the mass demonstration at Mel’s Drive-In, activists continued on to other establishments such as hotels and grocery stores. Under the guidance of the Ad Hoc Committee, activists gathered to protest the racist hiring practices of the Sheraton-Palace Hotel in 1964. This sit-in eventually became one of the largest organized in the city. The conglomerate nature of the Ad Hoc Committee used to effect change at Mel’s Drive-In allowed organizers and participants from a variety of groups to fight alongside each other with new ways of protest. Demonstrations at Mel’s Drive-In and the Sheraton emphasized the effectiveness of direct action and civil disobedience in civil disputes of San Francisco Bay Area, both of which had been energized by the Ad Hoc Committee. These protests, a hallmark of which had been their mass arrest tactics, introduced the local civil rights movement to “a new, more aggressive, and confrontational activist style.”(10)

Notes

1. Jo Freeman. "From Freedom Now! to Free Speech: How the 1963-64 Bay Area Civil Rights Demonstrations Paved the Way to Campus Protest."

2. "Bias Pickets at Dobbs' Drive-Ins," San Francisco Chronicle, 1963. Interviews with John

Dearman and Terence Hallinan

3. Babow, Irving, and Howden, Edward. A Civil Rights Inventory of San Francisco. June 1958

4. Miller, P. T. (2010). The postwar struggle for civil rights: African Americans in San Francisco, 1945-1975. New York: Routledge. Pg 75

5. This is from an interview with Tracy Sims, accessed here.

6. Outside Lands, Western Addition Project, Jul-Sept 2020, accessed here.

7. "Mass S.F. Sit-in Arrests—Dobbs, Shelley Argue," San Francisco Chronicle, Nov. 4, 1963; Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther, pp. 52-53. Accessed here. pg 85

8. Dobbs Says Picket Plan has Political Motive: http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/TextScans/Mels1.pdf from http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/textscans.html

9. From the Movement for Jobs in Civil Rights Era San Francisco, a thesis submitted for an MA by Larry Raphael Soloman http://online.sfsu.edu/socialj/context/context13.pdf

10. Weinberg, J. (1990). "Students and Civil Rights in the 1960s". History of Education Quarterly, 30(2), 213-224. doi:10.2307/368657 pg 219