Legacy of the Neighborhood Arts Program

Historical Essay

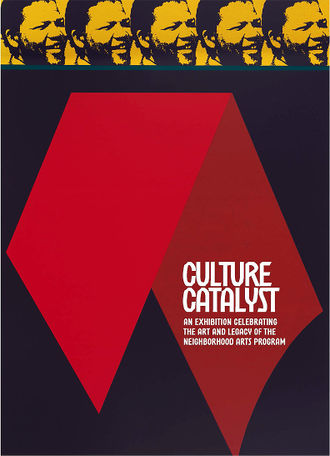

by Kevin B. Chen and Jaime Cortez, curators of April 27-June 9 2018 show at the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery called "Culture Catalyst: An Exhibition Celebrating the Art and Legacy of the Neighborhood Arts Program"

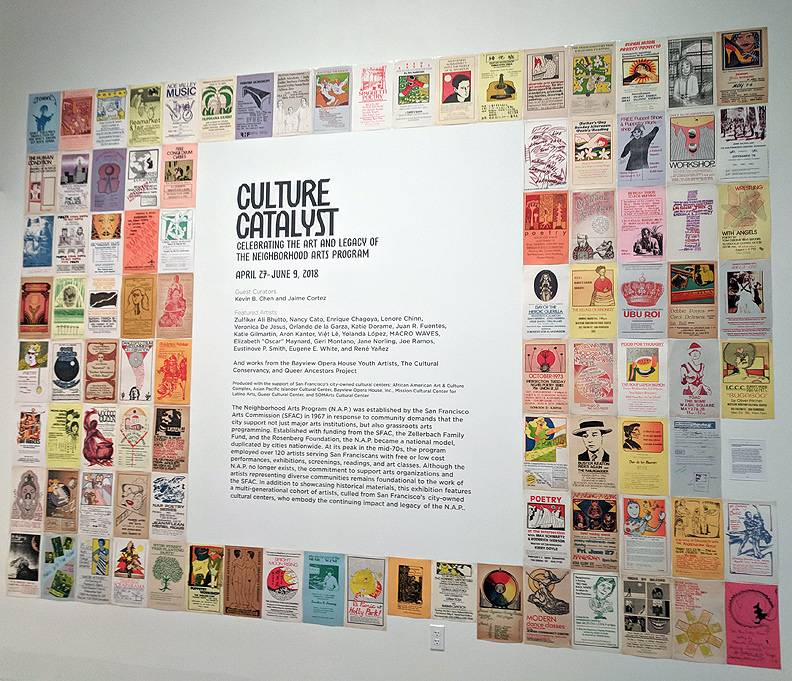

Introductory wall at SF Arts Commission gallery.

Photo: Chris Carlsson

By 1967, artists, cultural workers, and activists had been demanding for years that the City support not only major arts institutions such as the symphony, ballet, and opera, but also the presentation of arts in San Francisco’s diverse neighborhoods. Culture Catalyst celebrates the Neighborhood Arts Program (N.A.P.), the groundbreaking program born of this movement. Included in this exhibition are works by over 20 contemporary artists who represent the N.A.P.’s ongoing legacy and a celebration of the history of the N.A.P. with a display of hundreds of vibrant posters and flyers for neighborhood exhibitions, performances, screenings, literary events, and art classes supported by the N.A.P. in the 70s and 80s. As large as it is, the poster display gives but a small taste of the extraordinary artistic vibrancy the program unleashed and supported.

Program cover "Many Mandelas" by Juan R. Fuentes

Initially funded by the City (through the San Francisco Arts Commission), the Zellerbach Family Fund, and the Rosenberg Foundation, the N.A.P. provided a wide range of free or very affordable support services (costume bank, scenery bank, printing and design services, audio visual equipment and technicians, portable stages and stage trucks, affordable arts and crafts supplies at SCRAP, and more) to anyone putting on neighborhood arts programs. The program was vibrant and became even more so in 1974, when it began hiring artists to work in neighborhoods with dollars from the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), a federal program designed to train workers and provide them with public service jobs. At its peak in the mid-70s, the program employed over 120 artists creating and presenting work in neighborhoods citywide, and gave tens of thousands of San Franciscans access to arts classes and presentations in their neighborhoods. For working artists, participation in the N.A.P. was pivotal. According to exhibition artist Lenore Chinn, “As a San Francisco native and artist, I gained entry into the local arts scene through the Neighborhood Arts Program. Later, I exhibited at the City’s neighborhood Cultural Centers. There I connected with a community of artists, where resources were shared and creative ideas could be incubated.”

By the late 70s, the political and economic climate had changed, and budget cuts diminished the program. Although the N.A.P. no longer exists, its impact and legacy still resonate. For example, San Francisco’s six city-owned Cultural Centers were born out of tireless advocacy from neighborhood activists with support from the N.A.P. The contributions of the African American Art & Culture Complex, Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Center, Bayview Opera House, Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, Queer Cultural Center, and SOMArts are represented by the work of artists closely associated with these vibrant centers.

We have been thrilled to organize an exhibition that engages three generations of artists, with input from extraordinary veteran arts administrators and cultural workers. Our biggest challenge has been time. We were invited to work on this project only a couple of months ago, and have been operating at a breakneck pace to learn some of the program’s history, talk to a sampling of historic players in the N.A.P., and organize the work that you see in the exhibition. It has been humbling to learn of the great passion, vision, resourcefulness, and leadership of people involved in the N.A.P.. The program not only employed hundreds of artists, but brought art to hundreds of thousands of people of all ages throughout the neighborhoods of San Francisco. Given our timeframe, we simply could not organize a truly comprehensive historic and artistic survey of this important and impactful program. Nevertheless, we hope that Culture Catalyst helps us all imagine how the city, artists, community activists, and art-loving citizens can continue to support arts access for every San Franciscan.

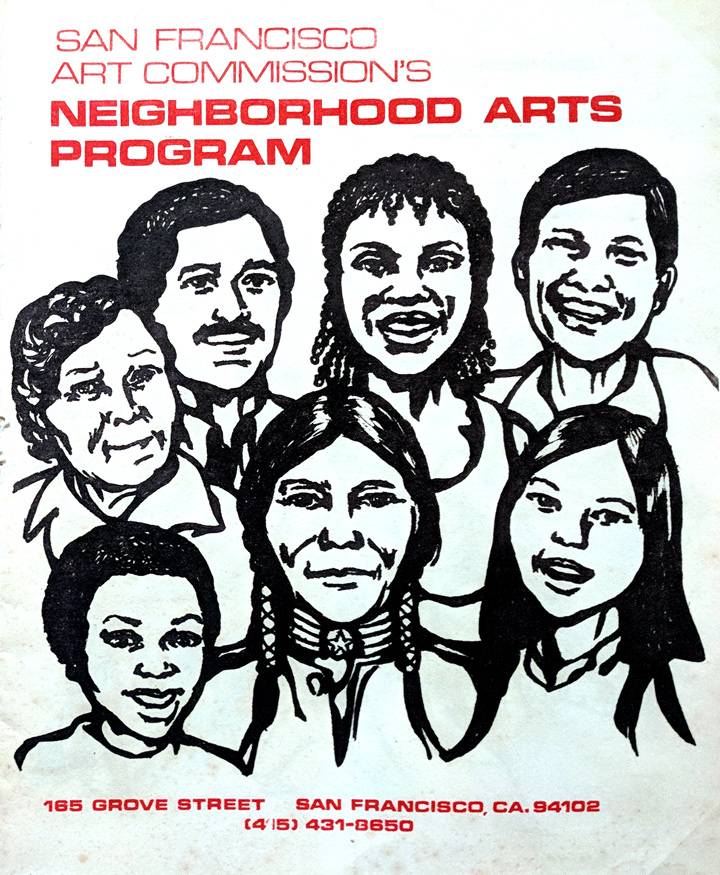

Neighborhood Arts Program booklet, April 1978.

Image by Jane Norling

I Was There . . .

“N.A.P. dance classes inspired me and sent me on my way”

—Alleluia Panis

The afternoon light came through the large windows revealing a spacious gym with hardwood floors, and cream-colored walls. My classmate Jane, a modern dancer, invited me to my first ever modern dance class. It was a short ride on the 30 Stockton bus from school to the free after-school program taught by Klarna Pinska under the Neighborhood Arts Program in the Salesian Gym on Filbert Street in North Beach. I recognized Rose, sitting with her back to us; her straight brown hair down to her waist, she was playing some classical tune on an old upright piano. I recognized three other girls from school: African-American Barbara with her short Afro and the ruddy-cheeked white girl Gaye were both tall, stunningly beautiful and trained in gymnastics and ballet. There was shy Susan, the only other Asian girl. Klarna Pinska, in her sixties, wearing a moss-green leotard and white mid-calf tights, slowly stood up from kneeling position and walked towards us. It was 1970 and I’m this immigrant girl about to take her first formal dance class, whose only done some folk dancing in grade school in the Philippines and one semester of dance in high school.

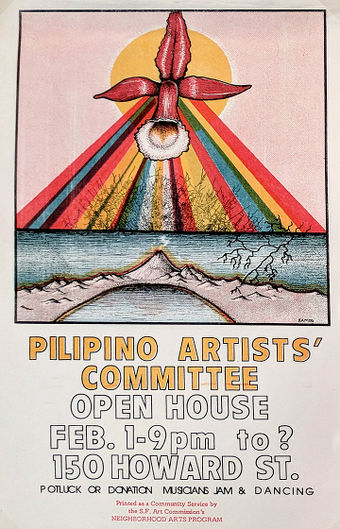

Image by Joe Ramos

We learned dances by Ruth St. Denis and performed them at various elementary schools. Klarna made me feel not too different from the other American girls even though they had more training than I did and they were of course, American girls. I was surprised when she started teaching me the solo Nautch Dance. I wasn’t ready and didn’t have the confidence to learn it, let alone perform it. But the idea that she thought I could do it somehow made me feel proud. Although it would take me an hour to get home by bus, I attended every week. In addition, it was free. Looking back, I’ve realized the dance classes became a much needed respite from the daily struggles of my immigrant life.

I was most fascinated by her stories of early American modern dance innovators like Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Ted Shawn, and Charles Weidman, who she personally knew. She would tell of their individual styles and their courageous ways of exploring movement and choreography. As a young person in a new country, these stories comforted my young mind in hearing artists creating and inventing despite conventions of the times.

As a young person uprooted from the homogeneity of my home county, I found the vividness, the boisterousness, and robustness of the sight, sounds, and scent of North Beach and Chinatown a marvelous adventure of familiarity and foreignness at the same time. She introduced us to book readings at City Lights, beat poetry at Enrico’s Cafe, free art exhibits at San Francisco Art Institute, and cappuccino and opera singing servers at Café Trieste. On my own, I explored Chinatown’s dim sum shops, and kung fu movies. Klarna gifted us, her students, the joy of dance, encouraged our curiosity for learning and participation. Klarna created a safe place for me to learn and be myself. Most importantly, she taught me that I have choices and exciting possibilities of what my American life can become. As the recipient of the first ever San Francisco Art Commission’s Artistic Legacy Grant, I am grateful for the ways the Neighborhood Arts Program dance class inspired me and sent me on my way as a working artist and community leader.

Alleluia Panis is a director, choreographer, and non-profit arts leader. She has created over twenty full-length dance theater works that have been presented on stages in the United States, Europe, and Asia. She has received numerous awards, including the inaugural Artistic Legacy Grant from the San Francisco Arts Commission in 2017. She is the Artistic and Executive Director of Kularts, the nation’s premiere presenter of contemporary and tribal Pilipino arts. Her newest dance/film/theater work, Incarcerated 6x9, will premiere in May of 2018 at Bindlestiff Studios.

I Was There . . .

“...a bright idea for community-building through art”

—Arlene Goldbard

If I could take you back in time, it would be to a sunny day in 1971. We’re standing outside the San Francisco Arts Commission at 165 Grove. The Commission’s office and gallery are downstairs, but we’re headed upstairs to the San Francisco Neighborhood Arts Program. N.A.P., that’s where the action is.

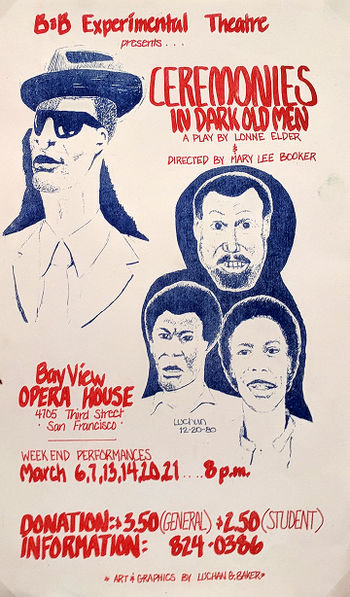

Image by Luchan Baker

As we can plainly see, it’s bustling. Think of N.A.P. as a community arts clinic—like the place you’d visit for a check-up, medical tests, a prescription. But here the focus is the well-being of the body politic, the cultural development of San Francisco neighborhoods. Who needs access to the means of art-making and dissemination? Who has a great project but needs help bringing it public attention? Who has the sensitivity, ambition, and skill to create a ravishing mural that unearths buried history, but needs paint, scaffolding, and a way to live while completing the work?

The underlying ideas are simple. Lives and communities throughout San Francisco are culturally rich; everyone’s experience is worthy of being uplifted into art; beauty and meaning are fundamental human rights, not elite privileges.

N.A.P. was organized by neighborhood, with each organizer given a territory, a salary, an actual budget and authority to deploy them. Sweet Michael Catlett (most didn’t know his sister was the famous artist Elizabeth Catlett—her 2018 New York retrospective just closed). Bernice Bing—Bingo—a truth-talking, big-hearted, inspiring artist and organizer. Buriel Clay, whose name is memorialized at the African American Art and Culture Complex theater on Fulton Street. That space was fought for in the 70s, folks in the Western Addition, Mission, Chinatown, Bayview, and other neighborhoods claiming a fair share of public funds that had been earmarked for red-carpet performing arts in Civic Center.

We walk through a labyrinth of offices and workspaces. Over here, people inquire about help with an art exhibit, concert, mural project, dance class, poetry reading, play. They talk to Jack Davis, a bear who purrs more than roars as he describes sound systems, a flatbed, and lighting, one object of desire after another drawn from the equipment bank to translate ideas into reality.

Here’s the print and design department where I worked from 1971 to ’73. We designed and printed flyers for community projects. Our technology was to today’s desktop publishing as moveable type was to cuneiform writing: Press-type (wax letters rubbed off onto paper); a photocopier to produce overlays by copying a copy of a copy. A Gestetner mimeograph machine: we made stencils on a fax-style cutter, attaching them to a rotating drum, forcing ink onto paper. It was labor intensive, madly inventive, and one of the purest expressions ever of art for the public good.

Let me emphasize public. N.A.P. wouldn’t have happened if creative, resourceful people hadn’t approached the City with a bright idea for community-building through art, if public funds hadn’t been invested. It wouldn’t have been able to subsidize so many artists if federal jobs money hadn’t been available coming off of the violent summer of 1968. And the idea never would have spread without John Kriedler writing one of the country’s first proposals to the Department of Labor for public service arts jobs.

I still have copies of the Bicentennial Arts Biweekly. December 18, 1974, describes “a queue of 300 unemployed artists—each hoping to get one of 24 new art positions recently made available by the Emergency Employment Act.” January 9, 1975: “Unemployed artists are being hired with federal funds in San Francisco in a program reminiscent of the WPA during the ’30s Depression.” Twenty-three artists had just begun to work at N.A.P. and the de Young Museum Art School at $600 a month. Applications were opening for 90 jobs for muralists to work in schools and housing projects, performing artists to work with community organizations and writers to work on neighborhood oral histories.

By the time the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) was ended by Reagan in 1980, CETA arts jobs had risen nationally to $200 million a year—and just about every artist active in community work had been given one, including local celebrities like Peter Coyote and Bill Irwin. The CETA arts origin story is contested, but I like to think it all started in N.A.P.’s messy, crowded, generative space where people from every background and life-choice built common ground, fed a never-ending conversation, and created a model of art in the service of community and equity.

Now, are you absolutely sure you want to go back to 2018?

Arlene Goldbard (www.arlenegoldbard.com) is a writer, speaker, consultant and cultural activist whose focus is the intersection of culture, politics and spirituality. She serves as Chief Policy Wonk of the U.S. Department of Arts and Culture and President of The Shalom Center. She was named a 2015 Purpose Prize Fellow and one of the YBCA 100 2016 for her work with the USDAC.

I Was There . . .

“You weren’t getting rich”

—René Yañez

Excerpts from an interview with René Yañez, conducted by Kevin B. Chen and Jaime Cortez on March 21, 2018.

How did you first become part of the Neighborhood Arts Program (N.A.P.)?

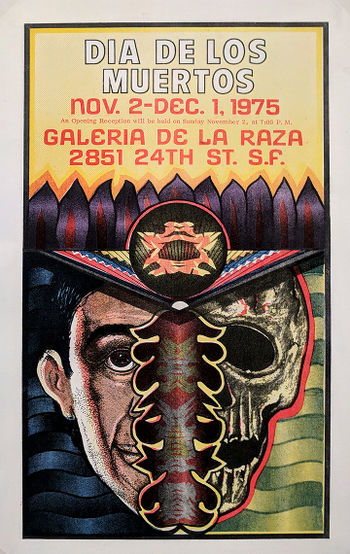

The way that the N.A.P. started, Harold Zellerbach (former President of the San Francisco Arts Commission) wanted to pass a bond for the Louise Davies Symphony Hall, and people turned it down, so he took it as a mission to educate people about the arts, so he hired people, well, through Marin Snipper of the Arts Commission, they started N.A.P. So it was the Mission, it was me, Maruja Cid, Alejandro Murguia, Roberto Vargas, they were a part of it. Different neighborhoods were getting represented. I worked with Rolando Castellón and we opened up the Galería de la Raza on 14th Street, between Valencia and Guerrero. We were getting together, we had exhibits, and Rupert Garcia, he brought an exhibit from Cuba, which at the time was quite controversial, it was around ‘69 or ‘70. There was people getting together, we had the first Chicana/Latina art show there on 14th Street, and that brought in a whole new community too. And there was an audience, an obvious audience. We had openings, people were coming. So, we were there, got evicted, and I found a place on 24th Street. The N.A.P. liked the location, we got support from them. Ruth Asawa was in the Arts Commission, she really helped.

Image by Joe Ramos

How long were you on the payroll for the N.A.P.?

Well, I was on the payroll for the N.A.P., then the CETA (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) program came. I had already been working since like 1969-70 for the N.A.P. They were liking what I was doing because we had exhibits, we had music, we had free classes, teaching silkscreen, Ralph [Maradiaga] was teaching movie making, I was teaching color xerox, so there was a lot of activity. People were taking classes, well they were popular, the merchants liked it, and also working at the Galería, when I saw that there was money in City Hall, I organized 24th Street Merchants, I was vice-president. We did beautification projects, things like that.

What are some important legacies of the N.A.P.?

Well, I think they created a whole audience in the neighborhoods for art, they gave classes, performances, movies, theater, music classes, I would go and see music lessons being done in the Western Addition, or the Bayview, I was very impressed. Here were 20 kids learning how to play instuments, and the teacher with a lot of commitment. You know, CETA, it was OK money, but you weren’t getting rich. [laughs] But the commitment that you had was, you know, it was a full commitment, and it educated a lot of people for the arts in San Francisco. It also had an influence in Oakland and other places. People saw it as a model, for what was happening.

SOMArts, they had the first Native American gallery there, then John Kreidler really liked what they were doing, so he moved them downtown where the foundation was, gave them a floor. John Kreidler was a big supporter, he really helped a lot of people, a lot of arts organizations. Because he would actually go and see the performances, go and see the exhibits. Before that, we was interning for the N.A.P., he also helped shaped the employment program. And then he got a job working in Oakland. I remember, because I knew people in Oakland and I helped him out getting some people doing some activities over there and so he started the N.A.P. in Alameda County. So there was a tremendous amount of activity, you can imagine—well, everyone was young, people had a lot of energy. Rupert was cranking out posters, Ralph was cranking out posters—we would get together and make a silkscreen poster calendar. We would sell it for a hundred dollars and people would complain, but there was like 13 silkscreen originals. So it was just a lot of activity.

Pioneering Chicano artist, curator, and community activist René Yañez is a well-known contributor to the arts of San Francisco, and is a founder of Galería de la Raza. In the early 1970s, he was one of the first curators in the United States to introduce Mexico’s Day of the Dead (Día de Muertos) as a contemporary focus and an important cultural celebration, and he curated one of the Bay Area’s first shows on Frida Kahlo.