J.B. Monaco: The Dean of North Beach Photographers

Historical Essay

by Richard Dillon, from North Beach: The Italian Heart of San Francisco, 1985: Presidio Press, Novato CA

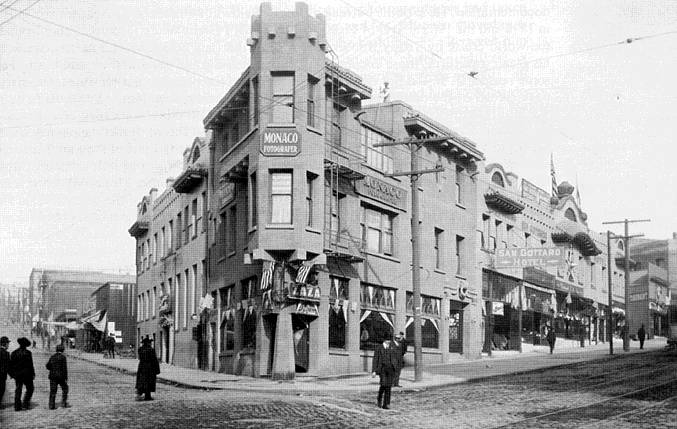

205 Columbus, Home of J. B. Monaco; between 1902 and 1906.

Photo: J.B. Monaco

| The Swiss-Italian immigrant Giovanni Batista (J.B.) Monaco and his brother Louis opened their photography studio to San Francisco in 1888, landing in the heart of city life. Monaco's professional work involved portraiture, but he is most famous for his photographs that captured daily life North Beach, the 1906 earthquake, and various other pivotal events in San Francisco's history. His career ended during the Great Depression, and this account describes his city life until he died in 1938. |

Like Cavalli, J. B. (actually Giovanni Battista) Monaco was born in Verscio, near Locarno, on December 12, 1856. In 1875 he stopped off in San Francisco en route to Eureka, Nevada, where he would join his brother Louis. J. B. liked to crack that his first job in the city was washing dishes in a whorehouse. He stretched a point; it was the Bella Union -- a melodeon, or variety theater. The place was famous, however, for its bawdy stage shows "for men only." J. B. was a painter of some talent, so Louis put him to work as color artist in his City Photographic Gallery, touching up and tinting photographic portraits. At the same time, Louis taught his younger brother the basics of photography.

Quickly, J. B. became as zealous and accomplished a photographer as Louis, although the latter continued to run the show. According to J. B.'s account of his early photostudio career (in a 1938 issue of Focus), it was not all wet plates, collodion, and albumen paper. "Anything could happen--and usually did.... The cash customers waited while the negatives were developed, and many the time J. B. pointed a finger of discipline as he shouted, 'You moved!"' As for children as camera subjects, he told another writer ("N. B.") around 1923, "Forty-six years ago, working the slow wet--glass process, we looked on babies, professionally, much as a bootlegger does on a Prohibition officer. But, now that everything has been made easier, they are as welcome as 'the flowers that bloom in the spring' -- when they don't cry."

In 1888 Louis Monaco closed his Eureka studio and opened a new one in San Francisco. J. B. had been in the city as early as 1887, scouting out possible locations. He chose 1228 Market Street between Taylor and Jones streets. Louis's grandnephew Richard explained the move: "The fortunes of a town change. If you were a photographer in a town that didn't work out, you'd go somewhere it did work out.... Louis and J. B. had good years in Eureka, but when things went to hell [there], their business went to hell with it."

The Monaco brothers were apparently as broke as Eureka itself. J. B. lived for some years in the studio while he was single. Louis had to farm out his daughter for a year or so to an aunt in Petaluma. But in 1894 the figli Monaco were able to move to 702 Market at Geary and Kearny streets. There, hard by Lotta's Fountain and just across the wide thoroughfare of Market Street from the historic "Bonanza Inn," the Palace Hotel, they were in the very heart of everything going on in the city.

In 1894 the brothers Monaco were able to move to 702 Market at Geary and Kearny streets.

Photo: J.B. Monaco

Business expanded at the choice location, but Louis died in 1897, and J. B. had to assume complete ownership of the firm at the same time he was courting his future wife, born in Collinasca, only twenty miles from his own Verscio. He met Katherine Batistessa in a North Beach restaurant, the Buon Gusto, situated in a building owned by her brother, Domenico. After a flurry of love letters from J. B., Katherine, then at the posh Hotel Rafael, a Marin County resort, surrendered. She was not a rich guest there, but a servant, a domestic and governess for such prominent San Francisco families as the Spreckels, the Hallidies, the Sterns, and the Greenbaums. J. B. and Katherine were married in San Francisco in 1898.

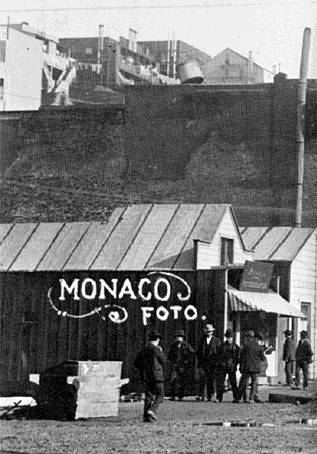

In 1902 J. B. returned to his roots, in a sense. He made a commitment to identify himself more closely with Little Italy than with the city at large. He moved his studio to North Beach, to 205 Columbus Avenue, still called Montgomery Avenue then. In 1904 he built a house at 2430 Leavenworth Street on Russian Hill above North Beach. The fire following the earthquake of 1906 took his studio, but spared his home thanks to the fire--fighting efforts of his neighbors and him. Once the embers had died and the ashes cooled, he put up a temporary studio on Broadway at the approximate site of today's Vanessi's Restaurant.

Monaco's business was portraiture, but his avocation was reportorial photography documentation. He shot the burning of Lucky Baldwin's Hotel and its Academy of Music in 1898 and the 1908 arrival of Fighting Bob Evans's Great White Fleet, sent on a 'round-the-world cruise by Teddy Roosevelt to "show the flag." Sandwiched in between were his greatest pictures, those documenting the earthquake and fire and their aftermath. For some reason, J. B. did not make these available to the press until after 1915. The sixty page spread of the earthquake, fire, and reconstruction special issue of L'Italia in 1907 was illustrated with cuts made from the photographs of Willard Worden and others.

After the 1906 quake and fire, Monaco built a temporary shack on Broadway (the name is marked on the negative, not the building)

Photo: J.B. Monaco

Renato Marrazzini, an ex-editor of L'Italia, told Lynn Davis, "I met the photographer [J. B.] in 1915. After a few years, he came down with photographs of the San Francisco earthquake. We published them in the newspaper. Then he was my photographer. I used to go up to his office and say, 'Make me beautiful!"' (Sometimes Monaco did just that. At Marrazzini's request he once added a moustache to a portrait of the editor so that the latter could send it to his aunt in the Old Country -- "to show her I'm a man," as Marrazzini put it.

1906 view down Broadway

Photo: J.B. Monaco

He did some work for L'Italia, but he was not the official photographer. . . . Mr. [Ettore] Patrizi was the official photographer. Mr. Monaco used to come down with photographs and Mr. Patrizi would pick some out and publish them in the newspaper. In 1914 we had the Verdi Monument in Golden Gate Park. I think he [J.B.] took one.

I would always joke with him, "Hey, are you in a good mood?" He was very thin, you know. Very tall, with a revolutionary hat.... He was very serious. He looked like a regular Swiss. He was a very pleasant man. I remember joking with him because we used to speak the same dialect. That's why I enjoyed him, because he was speaking my dialect. I remember saying to him once, "Monaco, let's go home to Switzerland and make chocolates." He was happy, but he said, "tempus fugit."

In 1908 J. B. made a pilgrimage to Verscio and his wife's Collinasca but left Katherine at home to take care of their son, Dante, born on November 12, 1900. J. B. named him for his nephew, Louis's son. Sadly, the older Dante was killed just seventeen days before the birth of the other "Dan."

In 1915, the year that Monaco bought a new home at 2434 Leavenworth Street, he photographed the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in the Marina, adjacent to North Beach. He secretly took pictures of Stella, the nude painting that breathed--the hit of the fair--and had a photographic scoop.

In 1920 Katherine died. About three years later, Monaco bought a building across the street from his studio and shortly moved his business there. He had two floors above a jewelry store, reached by a side entrance. On the first landing was his office; on the second his studio, with a glass skylight. J. B. remained in business there at 234 Columbus Avenue until a year before his death.

In 1937 J. B. took note of his sixty-one consecutive years in the photographic profession. But the depression of the 1930s caused his investments to collapse, and finally, in 1938, he lost his studio. In 1979 Dominic Camiccia told interviewer Lynn Davis,

The Bank [of America] foreclosed on him. My mother bought it [i.e., the studio] for me.... I had met him, J. B., before, through photographs we had taken of my family.... When I took the building over and Mr. Monaco moved out, he was in financial trouble. That's why he lost the building.... Between him and his partner, [Louis] Ferrari . . . he left a lot of glass plates, negatives; he must have left about two or three thousand of them. They were upstairs, all filed away in numerical order. He left them there and I asked him, "What do you want to do with them?" He said, "I don't want them. I have no place for them. . . ." So I put an ad in the paper, the classifieds, and I got an answer. I sold them for about two cents apiece. This fellow was just buying them for the glass. He figured he could strip off the negative and sell the glass for picture frames.

Monaco still had his books. He was an avid reader, especially of Dickens and of biographies of Napoleon and other historical figures. He was also fond of music, like most Italians and Swiss, particularly opera. And he had his beloved garden. He used to start working in it at 5:00 or 6:00 a.m. At 7:30, he would head for his studio. He kept this routine up until after he retired. Dick Monaco, remembering his green-thumbed grandfather, says today, "He was just crazy about gardening; flowers for everyone in the neighborhood. "

When Lynn Davis interviewed J. B.'s daughter-in-law, Mrs. Dante Monaco, she learned that the old man, who filed his dentures to better hold his cigars, was of such restless nature that he insisted on going to the studio even when he was ill. The family had to hide his clothes to make him stay in bed. Edna Callahan Monaco described her father-in-law as neither serious nor funny, but amiable. "Immediately on meeting him, you had to like him. . . ." He dressed casually but correctly in his later years and never went bareheaded. "He always wore a hat. Almost down to his nose. He had a beautiful head of hair. Why he had to cover it all the time, I don't know. . . ."

J. B. Monaco died on Christmas Day 1938. A member of Roosevelt Lodge No. 500 of the Masons, his December 28 funeral services at the Green Street chapel of Valente, Marini, Perata and Company were under Masonic auspices. He was buried in Cypress Lawn Memorial Park, Colma. The obituary in L'Italia stated, "He emigrated sixty years ago and, in a very short time, affirmed himself for his ability as a photographer, as an exemplary father and man of great heart, being loved by all those who were his friends, for his honesty and kindness."

As a young man, J. B. Monaco looked much more the dashing and debonair man-about-town than the homey family man and exemplary father that he really was. He was a dapper dresser, handsome and full of panache, with his fedora, probably a fine Borsalino, always cocked at a jaunty angle over his attractive, moustachio'd features. He definitely cut "la bella figura" on the streets of North Beach.

J. B. was a strong liberal, devoutly attached to Garibaldi. He also idolized another, greater, Italian. The Corsican corporal, Napoleone Buonaparte, was his great hero. Perhaps Monaco saw Guiseppe Garibaldi as a red-shirted reincarnation of Napoleon.

On Sundays, Monaco devoted himself to making pictures to record baptisms and weddings, at his studio. Some Sabbaths would find him coming home loaded down with silver dollars, payment for these happy camera sessions. All payment in those days was cash, hard cash. He also made fine, sensitive portraits of Fathers Piperni and Trinchieri of SS. Peter and Paul.

Monaco was very European in his style, his flair, but he was, at heart, 100 percent Americano. He Americanized long before his naturalization "took," probably from the moment he stepped ashore in New York, at age seventeen, on November 17, 1875. When he wrote home on his 1908 trip to Switzerland, his letters to Katherine were always in English, not Italian. They were full of breezy American banter and slangy gossip. He began them with "Dear Mamma and Kid ... .. Dear Old Woman and Kid," "Dear Young and Old, Saucy and Otherwise," and even "Old Bird."

For all his levity, Monaco had a serious side. He took his photography and his painting, though the latter was only a hobby, very seriously. (In the 1887-89 city directory, for example, Louis was listed as a photographer, but J. B. as an artist and a portrait artist.) He won a modest reputation early on for his charcoal and crayon drawings, if not for the mundane backdrops he painted for photographic portraits.

In a local paper, circa 1923, J. B. was profiled as "a Swiss photographer and painter of San Francisco's Bohemia." He liked that. He told his anonymous interviewer that, at the age of fifteen in Livorno, he got his first art lesson by mischievously ringing, repeatedly, the doorbell of an established artist. The man promptly boxed his ears for disturbing him. "But," added Monaco, "while he was 'massaging' my ears, my eyes were feasting over his roomful of paintings, and the result of it all was a lot of artistic and fatherly advice." The photographer told his interviewer, "For real pleasure, I say, give me a canvas, paints, brushes, pipe, and a pretty subject--if it isn't asking too much at sixty -- six."

Monaco was also pleased when the March 1938 issue of Focus, a magazine published by Hirsch and Kaye, the West's largest independently owned photographic supply house, devoted its lead story to J. B. and his work. The cover bore a halftone from a photo of his 1929 romantic painting of a Neapolitan boy. At eighty-one, he was in good health although only months away from his death. His years rested easily on his shoulders. But his pride would not allow him to admit that financial reverses had taken his studio from him. He told his visitor that he had decided to retire and had therefore closed his photography business.

Monaco reminded his interviewer that he had been painting long before he started taking photos. At age thirteen, in fact, he painted Vesuvius. However, he depicted the volcanic peak as it had appeared during the full eruption of 1833. He used pigments that he made of ash, charcoal, and pulverized brick. The rude but vivid canvas hung on the wall of his home. Today the painting is on display in Alessandro Baccari's North Beach Museum, on loan from Richard Monaco.

In his early days in the city, Monaco came to the attention of the prominent artist Domenico Tojetti and studied painting with him for several years. The Focus writer commented on J. B.'s distinctive style, "One must see his studies of Napoleon, Washington, and Lincoln to judge this quality." Obviously impressed by the still suave and jovial old gentleman, the writer closed the article by saying, "J. B. Monaco, photographer, painter, gentleman of leisure; we are proud to call him friend."

The Monacos formed a modest photographic dynasty. Louis, Marino, and J.B., were commercial portrait photographers, and more. J.B.'s son, Dante, won a mention in the Focus article: "His one son, Dan, is a motion picture engineer and technician of considerable prominence." His grandson Richard today owns Monaco Labs, a motion picture and video laboratory in San Francisco. Dick also has devoted much time to the rediscovery and appreciation of the pioneer photos of the Dean of North Beach Photographers, his grandfather, J. B. Monaco.

John B. Monaco's legacy to his adopted city is the collection of hundreds of photographs, both portraits and North Beachscapes, which survived the closing of his studio and are now in the hands of his grandson. When Alessandro Baccari opened his North Beach Museum in 1978, Kevin Starr wrote an Examiner story in which he compared the Swiss's work with that of Arnold Genthe in Chinatown. Both men were portrait photographers by profession whose best work was done in their avocational urban landscapes.

J. B. was more proficient with tins and film than such professionals as Willard Worden and such talented amateurs as Louis J. Stellman. Although not in Arnold Genthe's class as an instinctive artist, he rose above first-rate pictorial reporting to reach a kind of artistry. In his best pictures, his documentation skills fused with his sensitivity and compassion to suggest the depth of the human story behind the images.

Starr aptly described Monaco's stills as frozen motion, fragments of a continuous flow of life, like Genthe's Dupont Gai classics, rather than static and isolated compositions. Never arty or self-conscious (in spite of the romanticism of his paintings), much less contrived or doctored--"enhanced" -- images, Monaco's prints of the people and the scene in Little Italy are honest and understated. And, as Kevin Starr wrote, "Above all, Monaco obviously loved the world of North Beach. His portraits glow with affection."