Inside Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera's Life in San Francisco

Historical Essay

by Marisol Medina-Cadena

Originally published on KQED.org, and reposted here with permission.

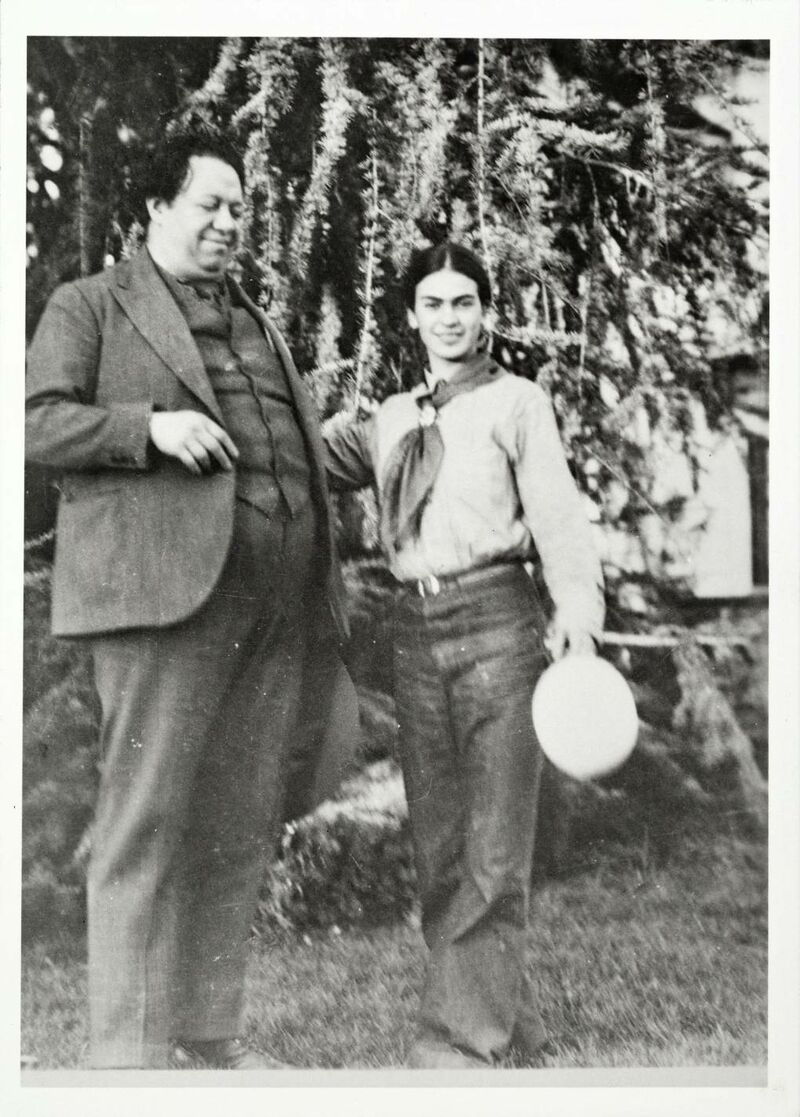

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera lived in the studio of sculptor Ralph Stackpole, on Montgomery Street, San Francisco.

Photo: Paul A. Juley/Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

These days, Frida Kahlo’s image is all around us. Her iconic eyebrows and piercing gaze have been immortalized on T-shirts, tote bags and tequila bottles. There’s even a Frida Barbie doll.

But before her image became so commercialized and ubiquitous, Kahlo was just a budding artist waiting for her big break. Married to the older and already famous artist Diego Rivera, Kahlo was determined to make a name for herself, and her time in San Francisco would help her do that.

Frida and Diego Come to San Francisco

It was a place she called “the city of the world,” and she often dreamed of it as a teenager, says University of San Francisco professor and author of Frida in America, Celia Stahr. As she and Rivera make their way to San Francisco in 1930, she doodles a portrait of herself set against a backdrop of how she imagined the city to be.

“When they get to San Francisco, she shows it to Diego and he just marvels at how much it looks like what they're seeing before them, kind of like she already knew what it was going to look like even though she'd never been [here],” says Stahr. “So there's a sense of destiny that she was supposed to come here.”

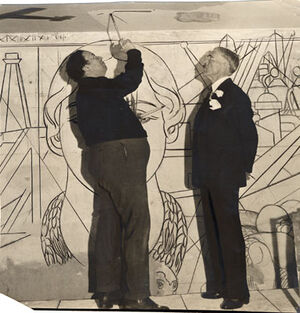

Despite the fact that it was the Great Depression and paid work opportunities for American artists were scarce, Rivera landed two prestigious mural commissions: one at the San Francisco Art Institute and another at the Pacific Stock Exchange building, now called the City Club of San Francisco. His patrons hoped that Rivera’s fame would bring prestige to the local art scene and help jump-start a mural movement in the bay.

Rivera at work on the 'Allegory of California' mural at the Pacific Stock Exchange.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

But Rivera was a controversial pick for the Stock Exchange. As a member of the Mexican Communist Party, Rivera imbued his politics in his large-scale public murals. Many San Francisco artists were outraged that an outspoken communist would paint in the city’s “citadel of capitalism” and took to the newspaper to express their opposition.

“I believe he is the greatest living artist in the world and we would do well to have an example of his work in a public building in San Francisco. But he is not the man for the Stock Exchange building,” argued painter Maynard Dixon.

Where his critics saw offense, his supporters saw beauty. Rivera’s masterful use of the fresco technique, applying pigment to wet plaster, fascinated local artists who eagerly wanted to learn the craft.

In one of the many letters Kahlo wrote to her family about the Bay Area, she notes the nonstop attention Rivera attracted. “The poor guy can’t even go to the bathroom in peace because they’re bugging him all day,” she wrote.

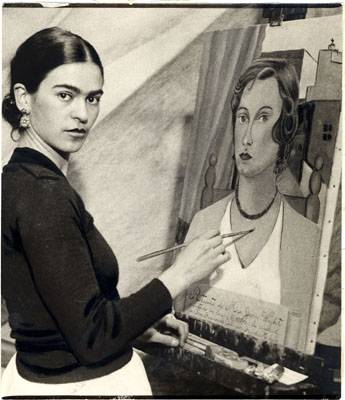

The 23-year-old Kahlo had only been painting for five years, and the local press merely regarded her as the wife of the famous Mexican muralist.

“She hasn't had that much experience. She hasn't really found her artistic voice quite yet,” explains Celia Stahr.

Soirees, Sketching and Sightseeing

In their new home at 716 Montgomery St., not far from North Beach and Chinatown, Kahlo was surrounded by artists who energized her creative process, says Stahr. For six months, the couple stayed at the studio of Rivera’s old classmate and friend, sculptor Ralph Stackpole, who introduced them to an eclectic group of writers, painters and photographers.

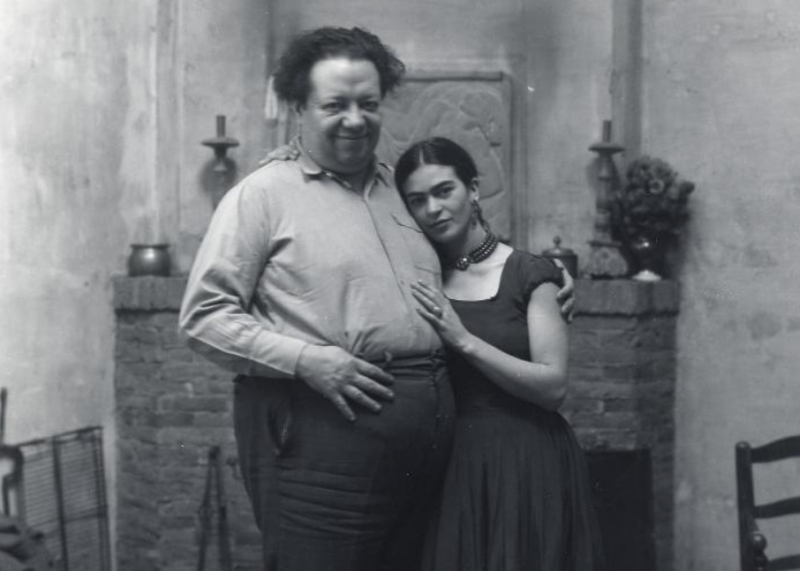

Rivera and Kahlo stay at the studio of sculptor Ralph Stackpole while living in San Francisco between 1930-1931.

Photo: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Among the many Bay Area-based artists they befriended included Dorothea Lange and her husband Maynard Dixon (who had warmed to Rivera by this point).

“The foursome talked art, politics, and the bleak times,” writes Stahr. “Dorothea’s need to respond to these desperate times appealed to Frida and Diego’s working-class sympathies.”

Part of Kahlo’s routine was getting together with Pele deLappe and Lucile Blanch to make art.

"We would draw these composite drawings where each one would start on a particular sheet of paper and then trade them off and pass them around,” recalled deLappe in an interview recorded in 2001. “[The sketches] were usually very obscene or horrendous and bloody or sensuous in some way.”

Pele de Lappe describes working with Frida Rivera

interview by Chris Carlsson

Art historian Celia Stahr says these hangouts were helpful for Kahlo’s artistic development.

When she and Rivera weren't busy painting, they made plenty of time for sightseeing around San Francisco.

“In the Russia colony they dress as they do in Russia, and the girls dance on the hills. The Greek colony is also very interesting and the Japanese, but most of all the Chinese,” Frida wrote in a letter to her mother.

“She just gushes about Chinatown and she writes about it quite a bit. It reminded her very much, she said, of home. She writes about how she's convinced that the Mexican people and the Chinese people are connected to one another,” says Stahr.

Letters detail how the firecrackers during Chinese New Year festivities reminded Kahlo of street fairs back in Mexico. Silks and other handmade fabrics sold in the shops of Chinatown also caught her eye. She purchased a few to embellish her red leather boots and make into Mexican-style skirts.

Kahlo’s style definitely caught the attention of San Franciscans. Her indigenous dress, influenced by the Zapotec women of Tehuantepec, stirred so much excitement on the streets of San Francisco that she reportedly stopped traffic.

“The gringas seem to like me a lot and they are really impressed by all the dresses and rebozos I brought with me, they gape at the jade necklaces and all the painters want me to model for the portraits,” Kahlo wrote to her mother.

Her bold look catches the attention of well-known photographers Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston, who ask her to pose for them in San Francisco. Since Kahlo was the daughter of a photographer, she was a natural in front of the camera. A local writer also pens a play about her and Rivera called “The Queen of Montgomery Street.”

Kahlo painting a portrait of Mrs. Jean Wight in San Francisco.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

This recognition adds to Frida’s growing artist persona and helped plant the seeds for her eventual rise to icon status.

But underneath her colorful garments, Kahlo’s body ached. At 18 she had suffered a horrific street car accident that severely damaged most of her body and exacerbated the chronic pain of her polio leg. Her long walks around San Francisco began to take a toll on her.

New Friends, New Places and New Ideas

That changed when she met Dr. Leo Eloesser, who would ultimately have a big impact on her life. Eloesser was the chief of thoracic surgery at San Francisco General Hospital and he went above and beyond to treat Kahlo’s foot and leg pain, even showing up at her doorstep when she’d miss her appointments.

Beyond his thorough care, he connected with Kahlo and Rivera on a creative level.

“Leo was a musician. He played viola and he would have weekly soirees at his flat. And so he was a doctor, but you could say he had the soul of an artist,” said Stahr.

The three of them even traveled around Northern California together. One time, Eloesser took Kahlo on her first plane ride. They flew from Oakland to Sacramento to meet up with Rivera who was busy sketching mines and dredgers for his "Allegory of California" mural. One of these excursions proved to be a major turning point for Kahlo’s art.

On a trip to Santa Rosa, Rivera and Kahlo visited the garden of the famous horticulturist Luther Burbank, known as “the wizard of horticulture.” He developed more than 800 varieties of fruits, vegetables and plants by cross breeding two kinds together.

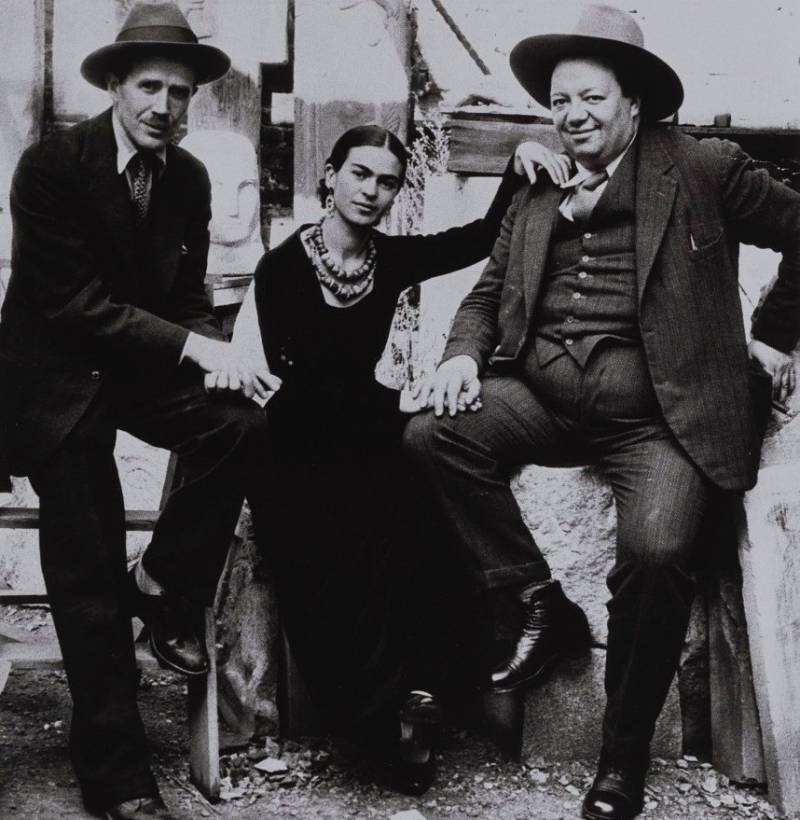

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo at the garden of Luther Burbank in Santa Rosa.

Photo: Luther Burbank Home & Gardens Collection—Sonoma County Library Digital Collections

Seeing how Burbank literally fused together two organisms to create something brand new mesmerized Kahlo. She applies Burbank’s hybrid technique to her art, and what comes out is a portrait of the horticulturist as part human and part tree trunk with roots connecting to his buried corpse.

“This is really her first major breakthrough creatively, in terms of creating a new style that was very different from what she'd been working on,” explains Stahr.

From this point on, Kahlo continued to play with imagery of roots, plants and hybrid bodies to portray themes of life and death. It's a duality that was already part of her Mexican upbringing, says Stahr, but a visual style that was honed here in the Bay Area.

When Rivera completed his two murals in 1931, the couple briefly went back to Mexico before returning to the U.S. to paint in New York City and Detroit. But it wouldn’t be the last time they visited San Francisco.

Frida and Diego Take on San Francisco a Second Time

When they return a decade later, Kahlo and Rivera are divorced, and they arrive following dramatic circumstances.

First came Rivera, who fled Mexican authorities who wanted to question him about the attempted assassination of his former friend and exiled Russian revolutionary, Leon Trotsky.

Kahlo wasn’t so lucky. Months later, when Trotsky was actually assassinated, the police detained her for questioning, believing she was an accomplice. (Years prior, she and Rivera offered their Casa Azul to Trotsky and his wife for political asylum). The brief experience in jail left her traumatized.

“She was in a terrible emotional state. Physically, she wasn't doing well. She complained of back and leg pain,” says Stahr.

In response, her doctors in Mexico advised her to undergo more surgeries. But her friend and trusted doctor, Leo Eloesser, didn’t agree. He felt her emotional health needed tending to, so he prescribed her a better diet, less drinking and advised her to reconcile with Rivera in San Francisco.

“[Eloesser] played this important role in their marriage. He was really the go between with their relationship,” explains Stahr.

Kahlo took his advice and when she arrived, she resided with Rivera at 42 Calhoun Terrace in Telegraph Hill before letting Eloesser admit her to St. Luke's Hospital in the Mission District.

Meanwhile, Rivera was busy working on his largest single standing mural, known as the "Pan American Unity" mural. For months he and his assistants painted in front of a public audience at Treasure Island during the Golden Gate International Exposition. (Watch this video clip of Rivera and his team painting at Treasure Island.)

Once again, Rivera’s art sparked controversy. Not because he painted his communist politics but because he portrayed the cruelty of Nazi Germany. It was his way of urging the U.S. to intervene in World War II and protect all of the Americas, including Mexico.

When Kahlo was discharged from the hospital and felt physically and emotionally stronger, she and Rivera remarried at San Francisco City Hall on Rivera’s 54th birthday.

The Oakland Tribune snaps a photograph of the couple and this time acknowledges Kahlo as “an artist in her own right.”

“By 1940 she has achieved quite a bit. You might say she's at the height of her career at that time,” says Stahr.

Her art was exhibited at the World's Fair on Treasure Island, the Legion of Honor and landed in the hands of an important collector, Albert Bender, who was affiliated with San Francisco Museum of Modern Art — all things that helped give Kahlo wider exposure around the U.S.

“You have no idea how marvelous the city is, it helped me a lot to come because it opened my eyes and I’ve seen lots of swell new things,” wrote Kahlo to a friend.(1)

Kahlo and Rivera remarry at San Francisco City Hall in 1940.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library

A Legacy That Keeps Evolving

As much as the Bay Area provided Kahlo and Rivera a platform to create and thrive, the couple also gave San Francisco a lasting blueprint for creativity.

“In fact, Coit Tower and the murals there emerge because of Diego’s influence,” says Stahr. Some of the Coit Tower muralists actually trained under Rivera, following in his footsteps by painting large-scale fresco murals that focus on workers and class issues.

His work also emboldened muralists at the Beach Chalet and UCSF. Ultimately, his patron’s desire for a mural movement to take off in San Francisco came to fruition.

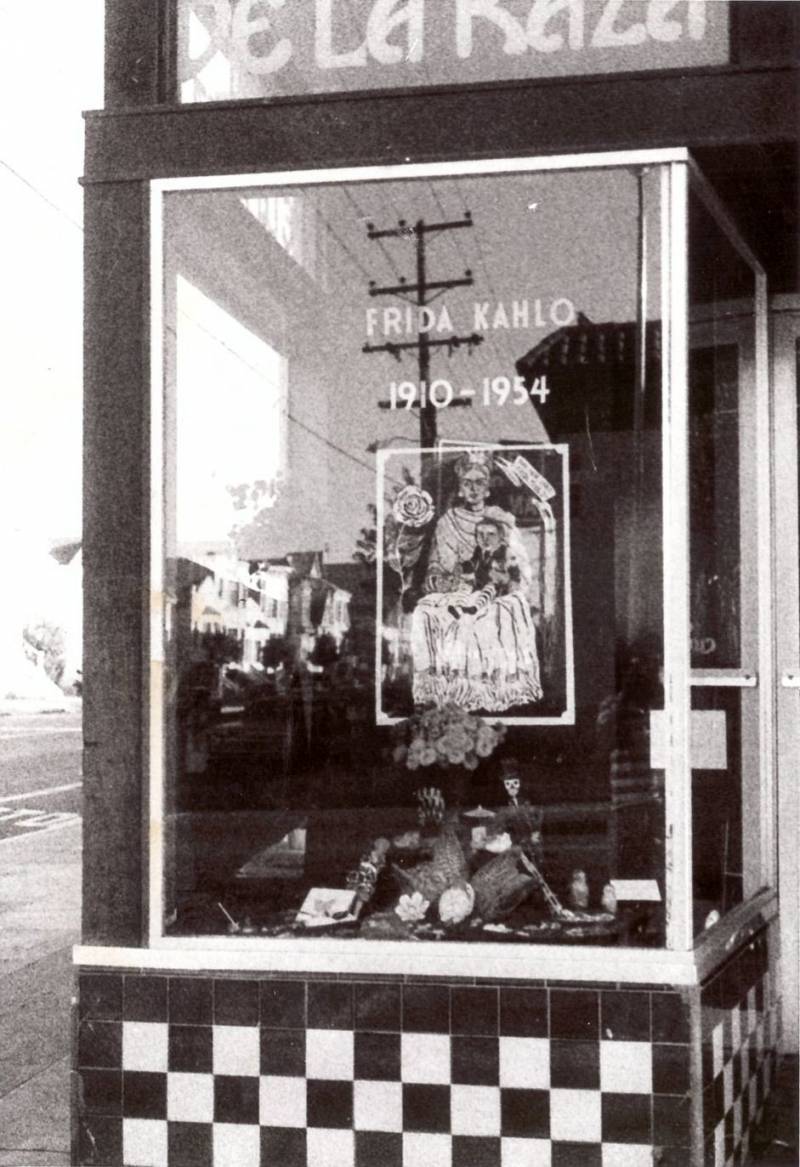

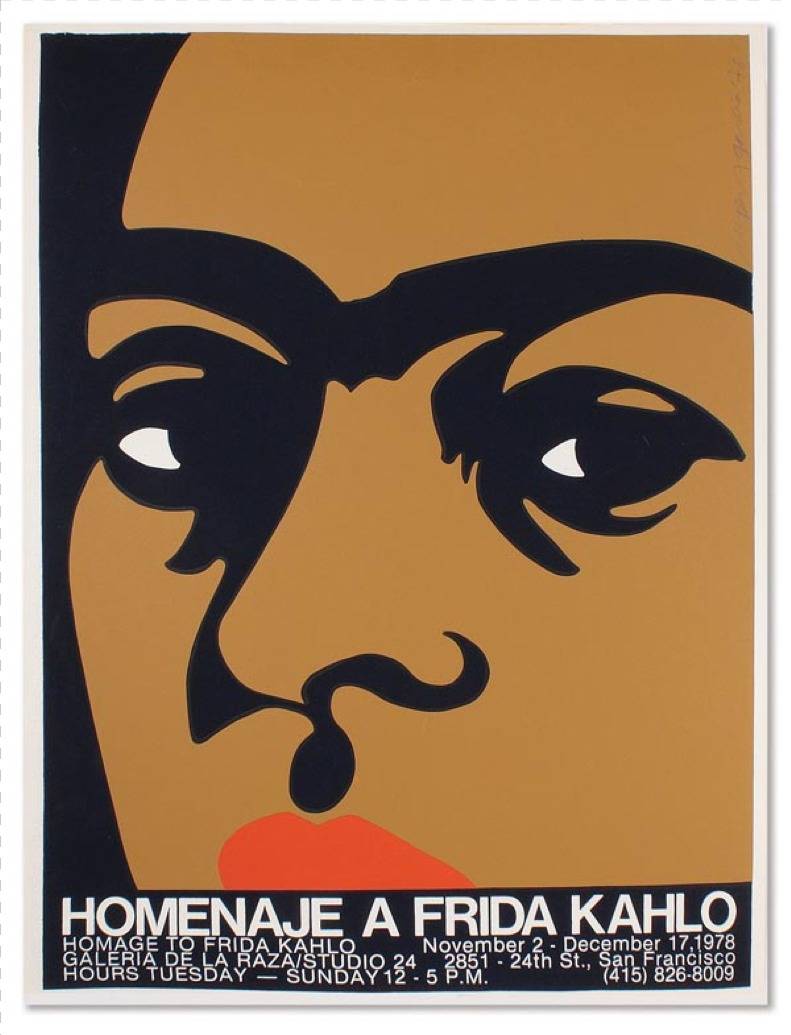

Starting in the 1970s, exhibits and events at La Galería de la Raza in the Mission District helped generate interest and appreciation for Kahlo's life.

Photo: Courtesy of Rio Yañez

Kahlo’s body of work also had a monumental impact on Bay Area artists, starting in the 1970s.

As many Chicanos and Latinos continued the fight for civil rights and representation, local artists like Amalia Mesa-Bains turned to Kahlo and Rivera’s art as a source of empowerment and cultural pride.

“We had experienced racism and discrimination and so we needed to reclaim our sense of belonging. Frida and Diego became in many ways models for us, that an artist could be at the same time political and cultural,” says Mesa-Bains.

Mesa-Bains and other Chicana/o artists were so moved by Kahlo’s complicated and bold art that they curated an exhibition called "Homenaje a Frida Kahlo" at the Galería de la Raza in 1978.

Poster designed by Rupert Garcia for the seminal 1978 exhibition.

Image: Courtesy of Rio Yañez

Artists created works inspired by Kahlo and those who personally knew the couple in San Francisco, such as Emmy Lou Packard, were invited to share memories of them.

This exhibit came at a time when there was very little published about Kahlo’s life and work, so it was seminal to introducing Kahlo to a wider audience before Frida-mania ensued.

Today, local artists continue to pay tribute to the two Mexican artists. Rio Yañez’s series, "Ghetto Frida," imagines Kahlo as a sort of comic book character hanging out at various spots in the pre-gentrified Mission District. And the political ethos of street art in the Bay hearkens back to Rivera’s masterpieces.

In 2009, Rio Yañez created Ghetto Frida's 'Mission Memories' to pay tribute to the iconic artist and favorite spots growing up in the Mission district.

Art by Rio Yañez

In 2018, San Francisco city officials renamed a street after Frida Kahlo in front of City College of San Francisco's main campus, also the permanent home of Diego Rivera’s "Pan American Unity" mural.

In what Kahlo called the "city of the world" the lasting brush strokes of Mexico's most known artists are as vibrant as ever.

The translated quotes from Kahlo’s letters to her family that appear in this article have been sourced from Celia Stahr’s book, "Frida in America: The Creative Awakening of a Great Artist."

1. Letter to Kahlos's friend appears in Frida by Frida collected by Raquel Tibol.