Huey Johnson, Land Conservationist

Historical Essay

by David Kupfer, 2011

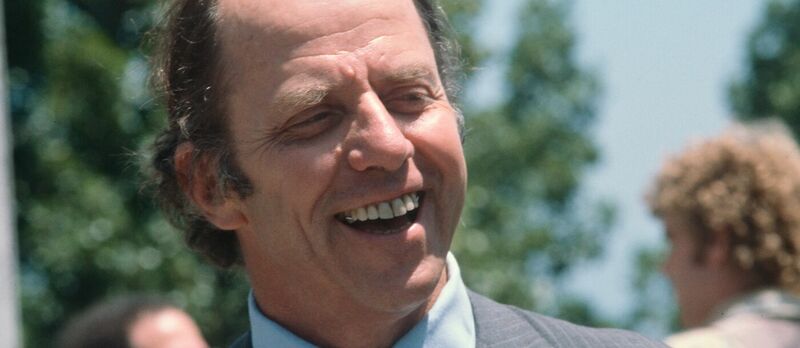

Huey Johnson in the 1970s.

Photo: courtesy Trust for Public Land

Huey Johnson began his career 50 years ago as The Nature Conservancy’s first employee west of the Mississippi River. As TNC’s western regional director, he established more than 50 land conservation initiatives before cofounding the Trust For Public Land in 1972. As president of the Trust For Public Land, he helped preserve more than 100,000 square miles of undeveloped land.

From 1978 to 1982 he served as Governor Jerry Brown’s secretary of resources, the state's top environmental official. He established water and energy conservation programs for cities and industries, doubled salmon numbers off the coast, and strengthened forestry policy. He led one effort that preserved 1,200 miles of rivers and another that preserved several million acres of wilderness in the West.

In 1983, Johnson founded the Resource Renewal Institute (RRI) which advocates for ”green plans,” long-term, comprehensive strategies for attaining environmental sustainability. In his spare time, he’s founded the Grand Canyon Trust, the Environmental Liaison Center in Nairobi, Defense of Place, and the Aldo Leopold Society.

David Kupfer (DK): What was your childhood relationship to nature?

Huey Johnson (HJ): I was lucky to have parents who cared a lot about the environment and who were determined to give me experiences important to that. We lived in a safe community in rural Michigan and as little kids we would go backpacking around Battle Creek River, a tributary of the Kalamazoo. My parents encouraged us to go out by ourselves and though it wasn't wilderness, as seven-year-olds, we'd often fish and camp. My parents trusted us, and that experience certainly impacted both my sense of independence and love of nature.

DK: You worked for Union Carbide in the 1950s. How did you switch from that into doing environmental work?

HJ: I was dead broke out of college and was offered a fine job at Union Carbide in Chicago. I was in a great position as a technical salesperson and was quite successful. One day I was in New York working out of the Union Carbide office there and after work, having a drink, could not hold my hand steady. I realized I hadn’t been in nature for weeks if not months, and one of my bosses that I really liked had just killed himself. In that moment, I began to question the whole thing. I submitted my resignation. My immediate boss told me he'd be fired since I had been so successful.

With a round-the-world plane ticket in my pocket, I walked past hundreds of my colleagues at their desks at the New York office for my final meeting with the big boss, one of the top executives of Union Carbide. His office had a stunning view of Manhattan, and he demanded to know why I wanted to quit. I told him. He had his back to me and finally he turned around, held out his hand, and said, "You lucky bastard!" He patted me on the back while telling me he hoped I'd do well. He essentially conceded that I was right and I think he was jealous.

DK: What did you learn from your world travels?

HJ: Visiting many ancient places around the world taught me so much about the result of human civilization and the repeated ruin of human history through resource depletion and mismanagement. It influenced me greatly, in particular visiting and learning about the battle and fall of Singapore and the Japanese' effort to occupy and gain control of Malaysia's natural resources.

DK: When did you first come to the Bay Area?

HJ: When I worked for Union Carbide back in the 1950s, they made the mistake of sending me to San Francisco for a two week seminar. They put me up at the Fairmont and gave me an unlimited expense account. It wasn't long before I thought, why would anyone think to live anywhere else? One day I took the cable car to Fisherman's Wharf and went salmon fishing the next day.

DK: How did you first get involved with the environmental movement?

HJ: I wanted to come back to the Bay Area but couldn't find an environmental job, so I did these menial jobs: I was at first a janitor for the California Department of Fish and Game. I wanted to make a difference and was soon promoted to being a seasonal biologist. My last assignment was up in Lake Tahoe. One day at lunch I was told that it looked like the state was going to wipe out a large portion of Fish and Game's budget and the program I was working for would end. After hearing that I said, “Let’s go to Sacramento to work it out,” but was told no, I couldn't do that as I was not a "professional." The next morning I saw a flock of geese fly overhead and had the thought that I didn’t want to make a career in a field where a couple of politicians could cut budgets and end good work. That day I resigned from the Fish and Game, hitchhiked from Tahoe to Reno and caught a plane to Alaska.

DK: What did you do in Alaska?

HJ: I worked as a biologist for Alaska State Fish and Game, tagging 12,000 salmon and hiking, looking for spawning salmon on Admiralty and Chichagof Islands in the Tongass National Forest, in southeastern Alaska, the largest national forest in the United States. It has some of the greatest large brown bear populations in the world. I saw them every day, and you really had to communicate with them to get around them, learn about their moods and make a noise to let them know you’re not a bear. If you didn't, you'd be punished!

DK: What did you do after your stint in Alaska?

HJ: I went to graduate school: a masters at Utah State in resource management and then back to Michigan for a PhD in resource and wildlife management, but I still couldn't find a job in the environmental field. I didn't give up though. One day I happened by the graduate bulletin board and saw a guy posting a flyer for the job of western director of the Nature Conservancy in San Francisco. I called them right away and got the job, and my wife and I drove out. I was so poor that for the first few nights, my wife and I slept at Muir Beach. I’m lucky to have lived in Mill Valley ever since, for the past 50 years.

DK: What are your favorite nature spots in the Bay Area?

HJ: I have had some very memorable times on a boat at sea out the Golden Gate, and I’ve done a lot of hiking in Marin on various trails; one of my favorites is the Dipsea Trail from Mill Valley to Stinson. I used to run the Dipsea Race. There are a lot of bluebird nests along that route.

DK: Who were your mentors in the early days of your environmental career?

HJ: Dave Brower was an important mentor in my life, and after I came out to begin my work for the Nature Conservancy, I was dying to meet him. My big chance was at a cocktail party soon after I had arrived. He asked me “What do you do?” I told him I was with the Nature Conservancy, and he asked, “What's that?” When I told him, he said, "If any land needs to be saved, the Sierra Club will save it!" Then he turned around and walked out! But we ended up becoming good friends.

Caroline Livermore, founder of the Marin Conservation League, was something else, a wonderful and tough early environmental voice. We were able to save the St. Hilary's Church property in Tiburon because someone had found rare endangered wildflowers, the Tiburon black jewel flower and the Tiburon Indian paintbrush, under the front porch!

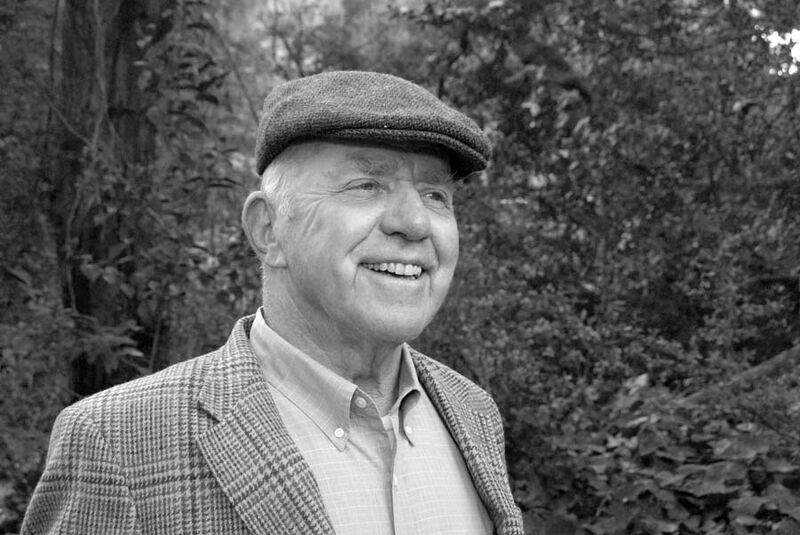

Huey Johnson, early 2000s.

Photo: courtesy Bay Nature

DK: What changes, positive and negative, have you seen in the local environmental movement?

HJ: Our popularity has certainly increased: We environmentalists have won enough to be socially respectable. People now happily pick up the green flag and adopt environmental values. But issues used to be much simpler: We used to be able to focus on a redwood tree or forest, get people fired up and create a national park. Today there is far greater complexity to issues, from air pollution and chemicals in the environment, loss of biotic diversity and climate change, threats to the ocean and loss of topsoil, things like economic issues and population pressures. Those things require far more explanation, education, and understanding for leaders to lead and to get the public behind individual initiatives.

DK: Why do you think eco-consciousness and institutions have taken root and flourished here?

HJ: The Bay Area is a final destination for a lot of frustrated people who grew up somewhere else where things were polluted and falling apart environmentally. People who live here care enough to take care of the place, and there are many kindred souls here who came from somewhere that was damaged. You can feel the sense of environmental kinship.