Huckleberry House and Teenage Runaways

Historical Essay

by Savana Huskins, 2021

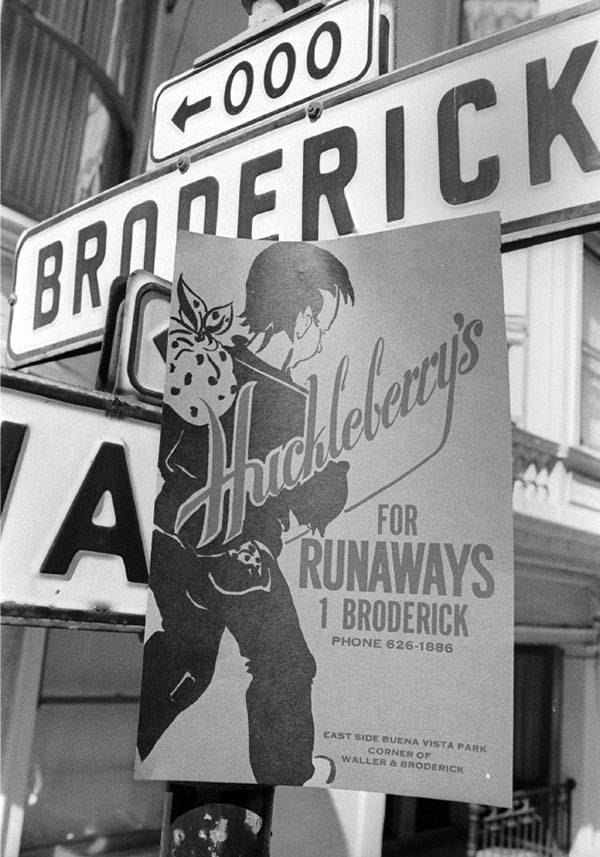

The original site of Huckleberry House at 1 Broderick Street.

Photo: Chris Carlsson, 2021

The Summer of Love is commonly known for its unprecedented attraction of young people from around the country to the Haight-Ashbury district. However, the reality for youth who were still minors was quite difficult due to their status as illegal runaways. In 1967 running away was a status offense, meaning it was an act that would only be considered a crime if committed by a juvenile. Most people in juvenile correctional facilities across the US were merely status offenders, not delinquents. These charges were also challenging to defend since a parent’s word almost always took precedence over a child’s.(1) Although the hippie community of the Haight-Ashbury district welcomed teenagers in concept, in practice many were not willing to risk harboring juveniles because it was illegal. The police could enter a home with no warrant if they suspected a runaway minor was crashing there. On the street, police could also request juveniles to produce identification at any time of day. Author Joan Didion was told of a fourteen-year-old girl who “was just walking through the Park...minding her own, carrying her schoolbooks, when the cops took her in and booked her and gave her a pelvic.”(2) If a runaway was picked up, they were sent to juvenile hall and could be kept there until parents were contacted and travel arrangements were made.(3)

The incarceration of youth was demonstrated all too well in the city-run Youth Guidance Center, which “was a bleak, overcrowded warehouse for boys and girls who had fallen into the hands of the law.”(4) A thirteen-year-old girl named Deveron described her time spent in its steaming hot rooms with tiny cracks for windows. “One day, some girls stood on their cots, broke the windows of their cells, and squeezed out through the barbed wire. They were torn and bleeding, but for the moment they were free, running through the cool mists of Twin Peaks.”(4) The current system for dealing with runaway youth was clearly failing these children. The Diggers recognized this problem and asked the Panhandle community for help. The solution provided by the Glide Foundation was Huckleberry House, which would be a safe place for runaways to receive guidance and needed resources while they figured out their plan.(3) Glide was a Methodist charity organization of progressive ministers that advocated for political and cultural change along with spiritual growth (9). They, along with other sponsor organizations such as the United Church of Christ and San Francisco Foundation, helped fund the new project.(5)

Huckleberry House opened its doors at 1 Broderick on June 18, 1967, with Rev. Larry Beggs and social worker Barbara Brachman as its full-time directors (3). Both Beggs and Brachman carried psychology degrees and had worked with kids for years in various youth programs. The house was also staffed by 25 volunteers, many of whom had experience working with youth and 4 of whom were clinical psychologists.(3) The first month was slow until these volunteers took to the neighborhood streets to get the word out (6). They made contacts with “key referral centers among Haight Street merchants”, locals, and community organizations that could direct runaways to the house.(5)

Flyer for Huckleberry House in Haight-Ashbury District (7)

Huckleberry’s aimed to help anyone over the age of 12 who came to their door with referral services, legal service, counseling, and food or housing, but using it solely as a crashpad was discouraged. The organization had to be careful not to break any of the laws regarding harboring minors, so parental consent was required for anyone who wanted to stay overnight.

Upon a teen’s arrival, they had an initial interview with the staff to discuss their situation. If they were willing to phone their parents, consent was obtained for any specific kind of help service that the teen may have needed, as determined with the help of the parents. Often, a meeting was arranged with the parents, teen, and staff as clarifiers of communication between the two.

Intimidation was lowered when the staff acted as a buffer between the teen, the home, and the police. Ideally, a better living situation could be worked out, and the house would often refer them to a family therapist in their home community.(5) If the family situation was not a safe space for the teen to return to, legal counsel was acquired and an investigation of the family would be conducted. They could try to declare the household “unfit,” but it was hard to accomplish because the justice system usually sided with parents.

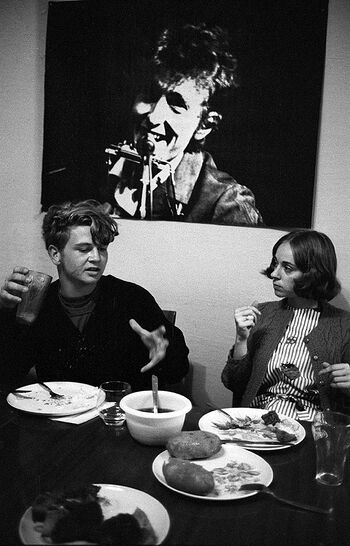

The rationale behind Huckleberry’s was a distinctly new way of approaching the runaway problem, in which it was addressed as a family matter instead of a police one.(4) The house believed that the current system failed runaways due to the “moralistic and punitive attitude of standard social agencies and elders attempting to intervene in the kid’s life.”(5) Instead, the teen should be provided with positive guidance and models, and should be allowed to find and express themselves creatively. The unique freedom the house offered was the freedom for the teen to “make decisions given endorsement by older, yet young adults who listened openly to them.(5) Directors Beggs and Brachman had youthful manners themselves, being in their early thirties. The house featured instruments, art supplies, and decorations including posters and photographs of the hippie scene to further make the youth feel comfortable. Bob Fitch noted, “It obviously belongs to the young people.”(6) A boy in the house said he “had to come all the way here to find someone to listen to me.”(6)

Kids having dinner in the house. (7)

In trying to facilitate the difficult task of conflict resolution between parents and children, Beggs picked up insights about why the number of runaways had grown so much in recent years. There existed a conflict of values between the two generations. The parent generation had grown up with a “depression mentality… security, affluence, goods centered.”(6) Security was of the highest importance and they had made compromises throughout their life to maintain it.

However, these values did not translate easily onto their children who had never experienced the nature of a depression. In addition, Beggs said there was a freedom conflict. “Kids want more freedom than their parents ever got. But the parent says, ‘while living in my house you are going to live by my value system.’ The kid is so mad at the parent he doesn’t even give him minimum information about himself and what he does.”(6) Beggs tried to point out this conflict and suggest an agreement between the two parties; sometimes they even outlined a written contract. For example, the teen would agree to keep the parent more informed and the parent would allow them a little more freedom. The goal was for there to be some change in the familial balance of power.

Rev. Ted McIlvenna, Director of Community development for the Glide Urban Center, admired the house’s work and also spoke on the runaway problem. “The problem is not caused by the Haight-Ashbury, but by the family...and the children are not always right… One of the tasks we have not performed is to teach children the necessary sensory apparatus to make choices in the city. Kids know they need this for survival.”(6) Thus, they were attracted to San Francisco and the experiences it had to offer. Joan Didion interviewed runaways Debbie and Jeff, who said their reasons for leaving home included chores, required church attendance, and parent’s disapproval of friends and clothing.(2) No matter if the home situation was dire and dangerous, or simply an inconvenience to the teen, the dialogue between generations was strained with frustration from both old and young.(5)

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/UE9fT1Kjk0c" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Huckleberry House sought to improve this dialogue on a personal, family level with ample counseling. It diverted from the typical systematic route for youth that involved law enforcement and punishment. After a crisis was solved, the house did not usually reach out to youth for feedback. Still, it proved successful in its work from the accounts we do have. A girl known for her short hair called it “a good place to live. You got a bed and food.”(6) A mother who came to the house from Oklahoma and had never seen hippies before called it “a very different experience...Many values are made by comparison. This has changed my values.

Yesterday the police asked me all kinds of questions about this house, but I told them what I knew and that it was clear to me they weren’t encouraging any wrong-doing. These people just seem to be trying to bring all the things together to help me.”(6) Huckleberry’s was the first youth center of its kind to show this level of success, paving the way for legislation like the Runaway Youth Act of 1974, which officially authorized community-based runaway and homeless youth projects to provide temporary shelter to kids.

Beyond the Summer of Love, Huckleberry House has remained a longstanding institution in San Francisco, where it continues to serve the needs of the youth population under the name of Huckleberry Youth Programs. It expanded its services in the 1970s with the Sexual Minority Project, which provided special outreach for LGBTQ youth, youth prostitutes, and sexual abuse victims. Supervisor Harvey Milk even wrote a letter to the organization expressing his excitement about this program.(10) As the house moved to 1292 Page Street in 1981, it helped advocate for the decriminalization of abused or neglected children running away from home.(10) It also focused on HIV education with a teen health clinic, eventually leading to the creation of the Cole Street Youth Clinic, which became the largest community-based adolescent health clinic in the city (10). The 21st century has seen Huckleberry Youth Programs expand further to include career training and college access educational, substance abuse services, and restorative juvenile justice models. Its impact has remained significant because it has added services to best fit the developing needs of at-risk youth. Congressional Research Service “identified family conflict and family dynamics, a youth’s sexual orientation, sexual activity, school problems, pregnancy and substance use as primary risk factors for youth homelessness.”(11) Females are more likely to run away than males, and LGBTQ youth have more than twice the risk of being homeless than their straight peers.(11) The updated programs reflect these demographics so that they can serve San Francisco’s runaway and homeless youth as effectively and with as much sensitivity as possible.

Huckleberry House at its current Page Street Location. It offers 24-hour crisis intervention and emergency shelter. (12)

Works Cited

1. Bishari, Nuala Sawyer. “A Flare in the Dark.” SF Weekly, 7 June 2017.

2. Didion, Joan. Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Simon and Schuster, 1968.

3. “Huckleberry House.” Haight-Ashbury Tribune, 1967. Stanford University Libraries. Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

4. Talbot, David. “The Lost Children of Windy Feet.” Season of the Witch: Enchantment, Terror, and Deliverance in the City of Love. Free Press, 2012.

5. “Huckleberry’s for runaways.” Regional Young Adult Project. ca 1967. The Bob Fitch Photography Archive M1994. Box 23, Folder 22: “Huckleberry House: Notes and Correspondence”. Stanford University Libraries. Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

6. Fitch, Bob. “Huckleberry’s for Runaways.” 1967. The Bob Fitch Photography Archive M1994. Box 23, Folder 22: “Huckleberry House: Notes and Correspondence”. Stanford University Libraries. Department of Special Collections and University Archives. Article notes and final text were referenced.

7. Fitch, Bob. “Hippie is a safe shelter for runaways: Huckleberry House”. 1967. The Bob Fitch Photography Archive M1994. Box 23. Stanford University Libraries. Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

8. Batten, Tony. “Huckleberry House & runaways”. KQED. May 22, 1968. San Francisco.

9. “Mission/Our Story”. Glide.

10. eport-.pdf “50th Anniversary Annual Report” (pdf). Huckleberry Youth Programs. 2017.

11. Homelessness Overview”. National Conference of State Legislatures.

12. “Crisis Shelter- Huckleberry House”. Huckleberry Youth Programs.