Housing Justice is Abolition Justice: Berkeley Renters Strike of 1970

Historical Essay

by Sarah Weaver, 2023

Reposted with permission from Freedom Archives

I started my internship experience at the Freedom Archives with an interest and academic background in local organizing struggles against resource capitalism, focally grounded in prior research on People’s Park. In exploring the Freedom Archives, I was inspired to focus on examples of abolitionist strategy present throughout local histories of tenant’s rights organizing, during the 1970s. Abolition wasn’t explicitly named as an ideological strategy in movements of that era, as the distinct term “abolition organizing" became popularized with the work of the organization Critical Resistance in the 1990s. Yet, many of foundational tenets of 1960s and 70s-era social movements overlap with the political strategies and goals that today we understand as integral to an abolition framework of socioeconomic and environmental justice. Abolition draws on grassroots organizing lead by rural and urban communities most impacted by systems of exploitation and displacement. In a 2020 interview with the Intercept, geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore, one of the founders of the abolitionist organization Critical Resistance, explained:

"..abolition has to be “green.” It has to take seriously the problem of environmental harm, environmental racism, and environmental degradation. To be “green” it has to be “red.” It has to figure out ways to generalize the resources needed for well-being for the most vulnerable people in our community, which then will extend to all people..to be “green” and “red,” it has to be international. It has to stretch across borders so that we can consolidate our strength, our experience, and our vision for a better world."

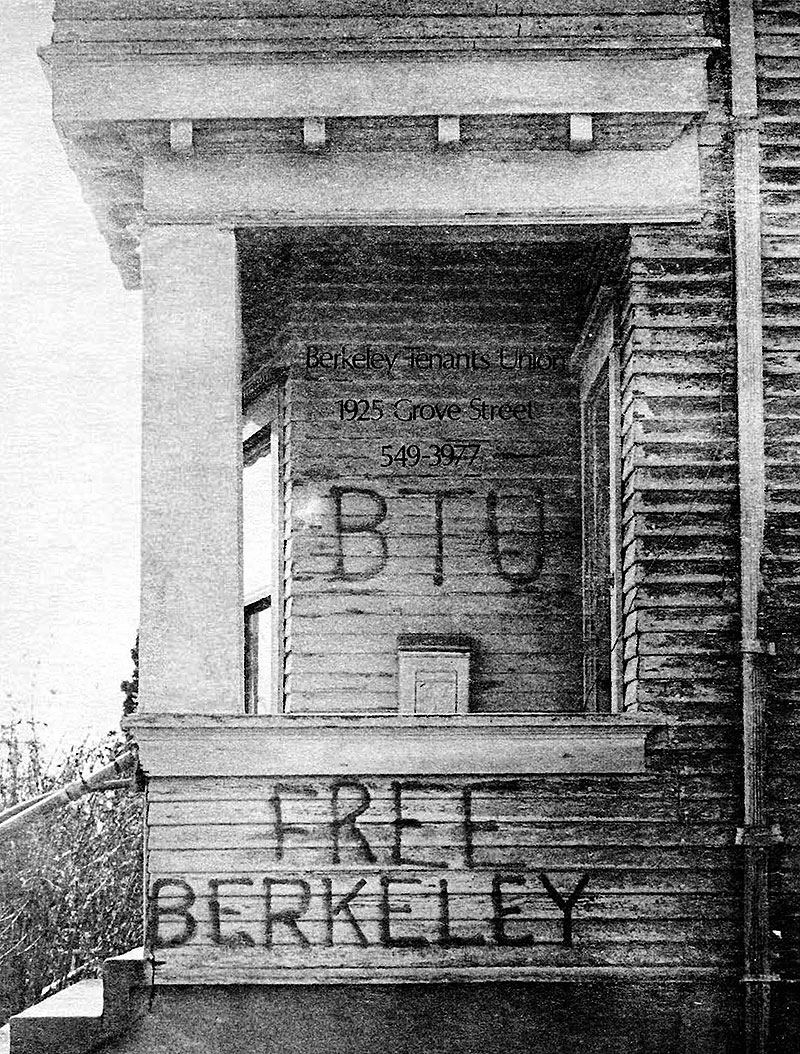

Here, I explore how three abolitionist tenets that Gilmore outlines—abolition is red, green and international—are reflected in archival materials from two intersecting local organizations that were active during the 1960s and 70s, the Berkeley Tenants Union and Tenants On Radical Change in Housing.

Berkeley Renters' Strike Timeline: For more information on the 1970 Berkeley Renters Strike.

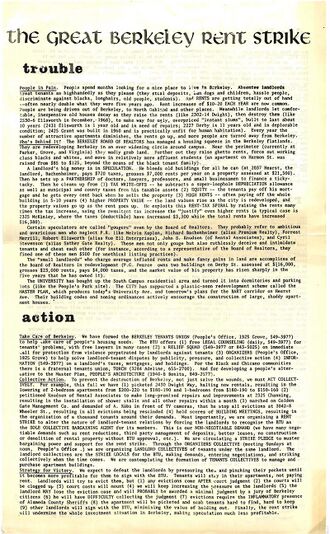

The Great Berkeley Rent Strike

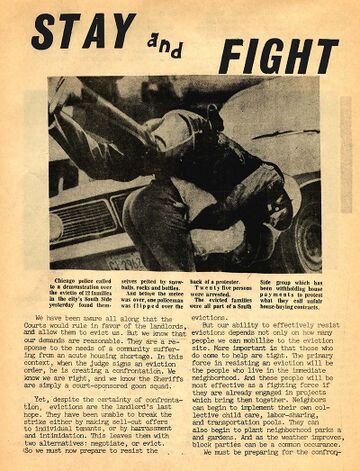

A two-sided flyer (pdf) produced by the Berkeley Tenants Union (BTU) which explained the reasons for the city-wide renters strike, as well as the strategies and goals for the action. Materials like this were most likely distributed to people who were known or possible renters across Central and South Berkeley, beginning at the end of 1969 leading up to the formal strike in February of 1970.

Subheadings “Trouble, Action, Doubt, Risk, Soul,” frame the main causes, stake and strategies for revolutionizing the geography of housing access for its audience. Given its organizing base overlapped with the proceeding radical student movements of the 1960s in the East Bay, the BTU was involved in organizing the student population of the University of California Berkeley who rented in the south campus area.

Across the city, absentee landlords could maintain profit through price gouging, sudden evictions, and racist, classist and ageism discrimination while ignoring tenant demands to fix common problems regarding unit safety. Through the union, the renter population could utilize the power of collective action.

Mostly white and middle-class, BTU organizers attempted to build cross-class and cross-racial solidarity in the context of the city and university administration’s goals to corroborate real estate profits by maintaining bourgeois demographics in Berkeley.

By making the organizational structure open to any and all renters, BTU activists attempted to build a widespread understanding of collective direct action as a necessary political strategy against the powerful interests of real estate speculation and development.

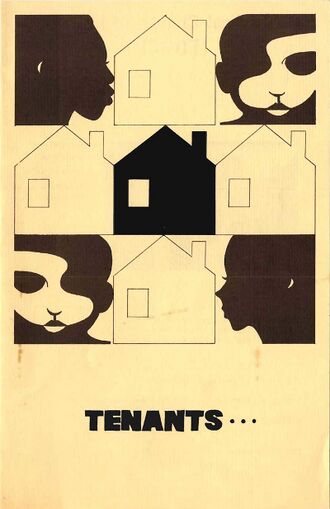

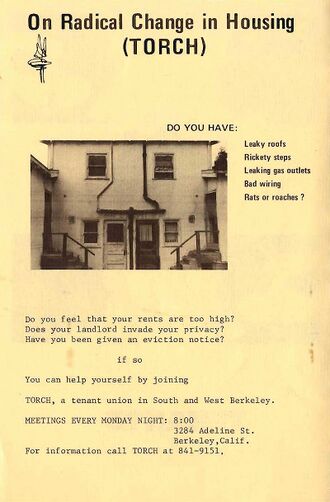

Tenants On Radical Change in Housing

Alongside the BTU, Tenants on Radical Change in Housing (TORCH) was an organizer collective that mobilized the predominantly working-class Black renter population of West Berkeley and the Flatland area into a tenant’s organization. The collective’s goal was providing negotiating support and legal aid for tenants facing persecution from landlords in court.

The TORCH acronym asserted that longer-term, radical structural changes were needed in the housing system, and the discriminatory economic system Black tenants faced at large. The name reflected the compounded structural barriers of displacement and exploitation that low-income tenants of color faced with the late 20th century rise of real estate capital. The groups choices in political framing of the problems at hand reflects the ideological and strategical impact of the Third World Liberation Front, the Black Panther Party, amongst other revolutionary, rank-and-file organizations in developing anti-capitalist organizing strategies that were principally linked to anti-racist and de-colonial political goals.

The working-class Black organizing base re-framed the local city government and the city of Berkeley and university's racist urban renewal policies by focusing on building the collective socioeconomic welfare of low-income black people in the city borderlands as the central political project at hand.

Renters were urged to join the union in order to practice participatory decision making—“You can help yourself by joining TORCH, a tenant union in south and west Berkeley.”—This statement centers self-reliance and highlights the organization’s orientation to fighting inequitable housing conditions and forcing change from the bottom up, rather than privileging the legal system as a tool for political change.

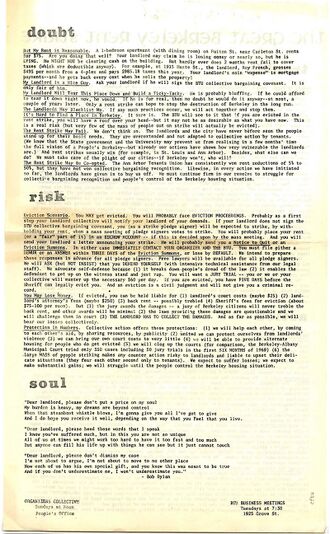

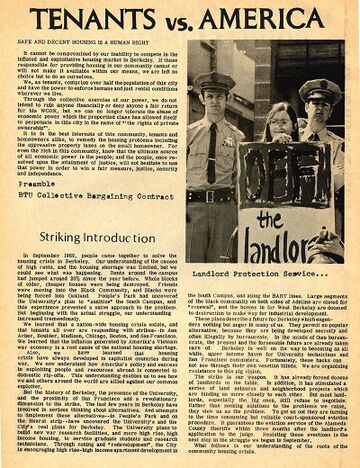

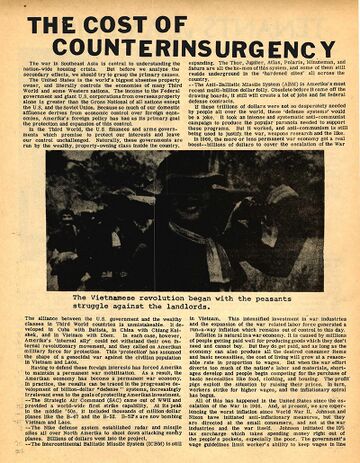

Tenants Against America

At the end of the 1960s, the U.S. government's military investment into the ongoing war in Vietnam caused inflation to skyrocket, and the cost of living spiked beyond the means of the working class communities attempting to build a lives in the East Bay. In turn, local tenants rights organizers identified the international scope of the economic crisis and the manufactured housing shortage. This fold-out pamphlet produced by the BTU mapped out the anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist political orientation and commitments of the Berkeley Tenants Union. The material includes reflections on the successes and failures of the solidarity strategy between the two sub groups across racial and class lines, and the continued goals of the organizations moving forward from the end of the strike.

Notably, this pamphlet starts with focusing on the development and struggle over People’s Park as a potential catalyst for widespread challenges to the capitalist housing system. Here, I will note that the overlap and continuity of people and ideas is vital for movements to grow and develop, a trend that is also seen in current movements. Oftentimes, organizers who cut their teeth fighting police murders of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown were leaders in the most recent Black Lives Matter uprisings of 2020.

Many BTU organizers were relatively inexperienced, with roots in the student movement struggles that flocked to the park in the years prior. The pamphlet targeted the University of California Berkeley’s 1965 Master Plan as a technology of “urban removal,” a suburban development plan for the city that relied on large-scale property acquisition, redevelopment and resulted in skyrocketing costs of living in the south campus area.

Importantly, organizers connected the urban removal interests of the UC Regents—its powerful body of economic shareholders and decision-makers—to Columbia University's urban renewal targeted at the heavily policed, Black, working-class neighborhood of Harlem at the same time. Further, we can see here that tenants were urged to follow the lead of tenants in Chicago fighting back against police-lead evictions in solidarity against the displacement of working-class people everywhere.

This pamphlet highlighted shared experiences of exploitation affecting renters city-wide, but particularly working-class Black communities. While emphasizing the urgent need for legal defense, the pamphlet also touched on the long-term importance of building non-hierarchical community relationships through mutual aid, for example “collective child care, labor-sharing and transportation tools.” Drawing on the real material needs of the city--from housing to childcare to food to transportation-- organizers prioritized an alternative, decentralized vision of resource distribution that would function for the entire community’s well being rather than for landlord, real estate company and bank profit.

The BTU’s political analysis extended beyond the university and city context, while implicating the University of California as a state corporation invested in the destructive, exploitative business of war. The pamphlet highlights how the overall property system links domestic real estate markets to U.S. international military profit.

The page titled “The Cost of Counterinsurgency” reminds the reader that “The U.S. is the world’s largest absentee property owner,” referring to the empire’s imperial control over the political systems and thus economies of Southeast Asia. The reader could follow along that the local state and university system was also wrapped up in the funding of counterinsurgency abroad as well as police systems, which were understood as a tool of force for completing evictions at home.

The pamphlet interrogates the University of California as a state corporation working to develop the intellectual knowledge necessary for U.S. military expansion, from fostering biochemical to nuclear engineering.On the local level, the pamphlet continues to explain that “landlords are using this shortage caused by the war to raise rents.” Here, Berkeley tenants rights organizers worked to build solidarity between the domestic working and middle-class tenants and national liberation struggles in Vietnam and Cuba. National and international struggles over housing as a capitalist or collective resource, from California to Chicago to South Vietnam, connect under one struggle for freedom from racial capitalism and imperialism.

Going Forward

In exploring the local radical tenants organizing history of the East Bay Area in the 1970s, we can see that grassroots struggles for equitable housing access came up against the mounting political investment in the expansion of militarism. During this period of heightened political-economic crisis, politicians and the mainstream media justified the ongoing investment in the state-subsidized war machine and the CIA's efforts in neutralizing revolutionary forces in Vietnam. In the Bay Area, the rise of rent and evictions was justified in similar ways, but also pushed back against with similar social movement strategies.

In the current era of continued state divestment from social services in favor of the expansion of carceral systems, robust grassroots struggles for housing to food security to environmental and educational justice are all tied to resisting this expansion. During periods of political-economic crisis like the end of the 1960s as well as today's recession, the capitalist class weaponizes ideas of social crisis—i.e. hierarchies of innocence and criminality to decrease social service funding—including housing, social security, and schooling—and increase military and police spending at home and abroad. Recent examples include the COVID-19 lock-down period when the organization Moms for Housing in Oakland organized low-income Black and Brown renters to resist targeted evictions. Furthermore, the Defend the Atlanta Forest movement has grown as a coalition-based movement to stop the construction of Cop City.

Engaging the work of BTU and TORCH provide interesting examples of radical social movement organizing that link issues of racial, economic and environmental justice. Communities have always resisted the inevitability of divestment and displacement and current abolitionist organizing weaves together the multi-issue struggles of the past few decades into a still evolving project to stop the capitalist and imperialist systems that ties housing insecurity and mass incarceration together.

Outside Sources:

Intercepted Podcast: Ruth Wilson Gilmore on Abolition.” The Intercept, 11 June 2020.

“BTU Fights Landlordism” The Conspiracy, Wisconsin Historical Society, GI Press Collection, September 1970.

Germain, Justin. “Berkeley Tenants Union in the 1970s.”

“Mission & Vision.” Critical Resistance.