Hotel Whitcomb: San Francisco’s Secret City Hall

Historical Essay

by Callan Showers

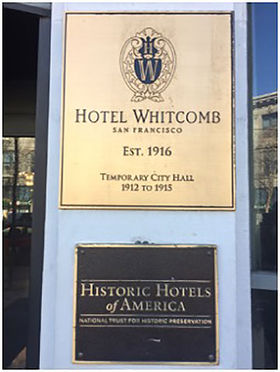

Front of Hotel Whitcomb on Market near 8th Street. The old words "City Hall" can still be made out above the entrance.

Photo: Callan Showers

| When the grandiose“Old City Hall” was decimated in the 1906 earthquake, government officials were left without a place of work. After four years of renting public space, the board of supervisors accepted an offer for the creation of a temporary city hall from the trustee of A.C. Whitcomb’s estate, James Otis. The seven story, reinforced concrete building cost $600,000 and took two years to build. It operated as city hall from 1912 to 1915, illustrating an example of private and public cooperation in the post-earthquake decade. The creation of the Civic Center in 1915 marked an end to Hotel Whitcomb’s time as City Hall, but today, the hotel is still in operation and the remnants of the words “City Hall” can still be made out above the entrance. |

A project that took the city of San Francisco 27 years and six million dollars to complete was destroyed in one day. The devastating 1906 earthquake brought down the grandiose Old City Hall only nine years after its opening. Nine years later, in 1915, San Francisco hosted the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE), a symbol of its recovery from the quake with the expansive Civic Center at the forefront. But where did city officials work between these two monumental occasions? For three of those years, the answer is Hotel Whitcomb, which served as San Francisco City Hall from 1912-1915. The Whitcomb’s role in San Francisco’s rebuilding after the 1906 earthquake is an example of efficient development in two decades otherwise marked by prolonged progressive-era projects. San Francisco police officer E.J. Plume was on duty in City Hall at the time of the earthquake and reported his experience, saying he “could hear the massive pillars that uphold the cornices and cupola of City Hall cracking with reports like cannons, then falling like lumber. Huge stones and lumps of masonry came crashing down outside our doors; the large chandelier swung to and fro, then fell from the ceiling with a bang. In an instant, the room was full of dust as well as soot and smoke from the fireplace” (quoted in Haas).

The Old San Francisco City Hall after the 1906 earthquake

Photo: Private Collector

Progressive leaders immediately turned their eyes to the future. On April 29, 1906, ex-mayor James Phelan said, “This is a magnificent opportunity for beautifying San Francisco…I am sure that the City will rise from its ashes greater, better, and more beautiful” (quoted in Haas). Phelan and others, like Daniel Burnham who authored the 1905 Burnham Plan, sought to rally the city towards “City Beautiful” ideals. They believed the earthquake was a unique opportunity refine public taste and promote respect for the state (Cherny), and were willing to spend money on precious real estate and big builds.

However, the bureaucracy of these “progressive” visionaries and corruption in local politics led to a lack of progress. Under Mayor Eugene Schmitz, the board of supervisors decided to construct a temporary municipal building on the block at Van Ness, Fell, Hayes, and Franklin, which the trustees of the public library had purchased in 1905. However, the trustees successfully sued on the basis that it was not public land to be seized and forced the city to keep renting space wherever they could (Haas). Days after the Court found in favor of the trustees, Schmitz was indicted for extortion of funds from “French Restaurants” (places of prostitution) and a period of changeover within the Mayor’s office began. With all eyes on the political scandal, attention was diverted from City Hall (Haas).

Following Schmitz, the corrupt Charles Boxton was mayor for only one week in July 1907 until physician and attorney Edward R. Taylor, a progressive, was appointed. Taylor’s board of supervisors created a 6-person “select committee”who financed a $2,500 study on the appropriate next step, eventually concluding in October 1908 that the old city hall was not recoverable and needed to be demolished.This demolition took six months and cost $50,000 (Haas).

As the city continued renting space for its various offices wherever it could, the question became whether to rebuild permanently on the site of the Old City Hall near Market on Larkin street (where the Main Library stands today) or invest in a new, expansive “Civic Center” including City Hall and other public spaces on Van Ness and Market. This ignited a debate between those concerned about practicality and those focused on beautification. Phelan, Taylor, and the same people pushing for “City Beautiful” advocated for the Civic Center and recommended funding the project through bond issues, while parties like the SF Chronicle and SF Labor Council favored the Old City Hall site and avoiding issuing bonds after a time of crisis (Haas).

The bonds were shut down in a public vote in 1909as city politics were also in flux. At 70 years old, Taylor made up his mind not to run for another term in 1910 and was unwilling to continue furthering the cause of civic center bonds (Haas). No other progressive champions arose to succeed Taylor. Instead, the Union Labor Party, infamous for Abe Ruef and corruption under Schmitz, rose to power once again when Mayor P.H. McCarthy in November 1909.

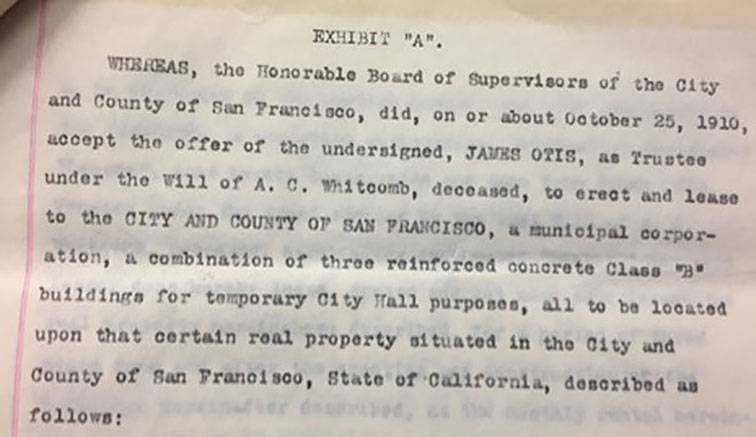

McCarthy and other new Union Labor Party Supervisors quickly began exploring private development offers for construction of a temporary city hall in 1910. Because McCarthy was a leader of the Building Trades Council (BTC), he was considered a representative of both labor and city government (Issel and Cherny) and likely saw this opportunity for public and private cooperation as a way to put BTC members to work and move the city forward. On October 25, 1910, McCarthy and the supervisors accepted an offer from the Whitcomb Estate Co. to construct a seven-story building on the Estate’s property on the south side of Market between Eighth and Ninth Streets (Haas). Estate trustee James Otis made the deal with the city that the building would house all city agencies currently in rental space with the intention that it “may eventually be used as a hotel” (SF Chronicle). Architects Wright, Rushforth, and Cahill designed the building with reinforced concrete with strict requirements for the building set forth by the board of supervisors. McCarthy broke ground on the hotel on December 19, 1910 – less than a year after coming into office (Haas).

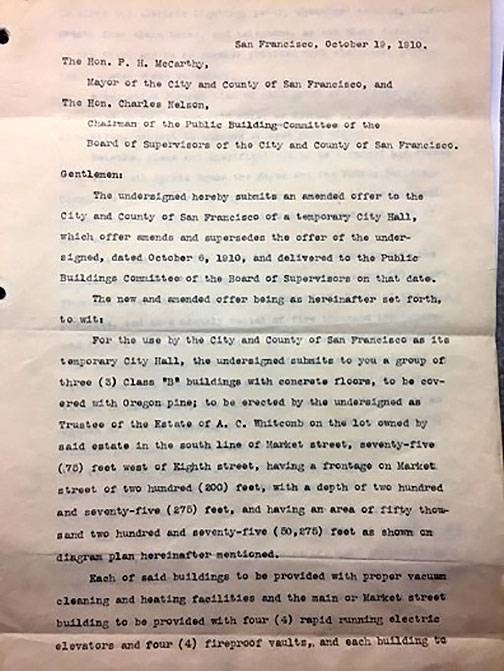

Initial Offer from Mr. James Otis, Trustee of A.C. Whitcomb

Image: SF Public Library. SF bldgs. Hotel Whitcomb

Acceptance of Offer from SF Board of Supervisors

Image: SF Public Library. SF bldgs. Hotel Whitcomb

In Otis’s initial offer, the attention to the cost of the lease demonstrates the Whitcomb Estate’s desire to profit from its deal with the supervisors. In their agreement (the Whitcomb estate being the “lessor” and the supervisors being the “lessee”) the lessee agrees to pay rents, charges costs, and damages on or before the 15th of every month. The monthly rent was set at $5,250 and they signed a three-year lease with the possibility for monthly renewals (Initial Offer). Compared to prices the city paid for space in other private spaces, this was significantly more expensive. From 1909 to 19011, five floors of the Hewes Building on Sixth Street cost $1,730 per month (Indenture of Leases).The Whitcomb was concerned with clearing themselves of liability and ensuring that they would get paid.

However, the state’s power over structural and design details in the agreement shows that it was a mutually beneficial agreement. The building, although intended to be used as a hotel in the future, was created as a city hall, and the lessee had power over the floor plans: the first floor housed the County Clerk, Tax Collector, and Assessor, the second floor the Supervisors, Fire Commissioners, and Board of Education and so on for seven floors. They even had a Central Emergency Hospital (Initial Offer). This custom-made aspect explains the higher rent prices; although the Whitcomb estate sought to benefit from the deal, the state did not have to sacrifice any needs of their specific offices.

SF Chronicle Article on the creation of the temporary city hall, December 17, 1910.

Image: SF Public Library. SF bldgs. Hotel Whitcomb

The Whitcomb cost $600,000 and took two years to build. During 1912, its first year as City Hall, Mayor John Rolph took office. Rolph ran on the promise of a new, full-time City Hall and other civic accomplishments in preparation for the upcoming 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) (Issel and Cherny). In 1913, ground broke on the new City Hall after voting on a bond issue to fund the construction of the Civic Center in 1912 (Haas).

The quirky narrative of the Whitcomb was not lost on SF residents. For example, an article called An Adventure at the Whitcomb in the SF publication The Main Sheet tells the story of an elderly woman who approaches a man at the door with a tax bill and six silver dollars and is confused when he tells her he is not the tax collector.

“I beg your pardon,” she answered. “Which is the tax collector’s office?”

“You will find it in the City Hall, madam.”

“But this is the City Hall,” she answered.

“It used to be,” explained the presiding genius of the news and cigar stand in the marble lobby. “But it is now the ‘Hotel Whitcomb’.”

And Billy gallantly escorted her across Market Street and directed her to the city hall. The article goes on to describe how the Whitcomb’s transition into a Hotel was “not to have an experimental stage at all.” It explains how though the idea of a “hotel de luxe” taking the place of what was once City Hall is exciting enough, the “remarkably moderate rates,” the sun lounge built on top of the seventh floor, and the marble lobby cut from “the famous quarries of France, Italy, the Mediterranean, and Africa” will make the Whitcomb a “social force” that is “destined to have a large influence in making the Civic Center the social focus of the city” (Main Sheet). The Whitcomb’s mutualistic nature with public spaces continued, apparently, into the new Civic Center.

Hotel Whitcomb’s time as City Hall was marked by tension between disaster and “Progressive” ideals. The Old City Hall was created at a time of rapid immigration and urbanization; the New City Hall at a time of desire for recovery in the public eye. It stands out as an example of efficiency and cooperation between public and private entities. Today, Hotel Whitcomb is a “Historic Hotel of America,” but more importantly, knowing its history adds to an understanding of governmental and industrial relations in the decade after the 1906 SF earthquake.

Photo: Callan Showers

Works Cited

1. "A Seven Story City Hall for San Francisco." The 'San Francisco Chronicle (1910) Print. SF Public Library, San Francisco, California. SF Bldgs. Whitcomb Hotel.

2. "An Adventure at the Whitcomb." The Main Sheet. Print. SF Public Library, San Francisco, California. SF Bldgs. Whitcomb Hotel.

3. Cherny, Robert W. “City Commercial, City Beautiful, City Practical: The San Francisco Visions of William C. Ralston, James D. Phelan, and Michael M. O'Shaughnessy.” California History, vol. 73, no. 4, 1994, pp. 296–307., <www.jstor.org/stable/25177450>.

4. Haas, James W. "San Francisco and the City Beautiful: A History of the Civic Center - Part 1." The Argonaut. San Francisco Museum and Historical Society 26.1 (2015) Print. SF Public Library, San Francisco, California. SF Bldgs. City Hall.

5. Indenture of Leases. SF Public Library, San Francisco, California. SF Bldgs. City Hall.

6. Issel, William, and Cherny, Robert. “Mayor Rolph and the New Civic Center.” FoundSF. Web.

7. "Mayors 1902-1912." FoundSF. Web. 14 Mar. 2017.

8. Nolte, Carl. "SF City Hall ruins from 1906 quake found." Sept. 24, 2012 Web.

9. Otis, James. "Offer to the City and County of San Francisco." (1910) Print. SF Public Library, San Francisco, California. SF Bldgs. Whitcomb Hotel.