Game of Politics

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Typical polling place competition for votes, 1880s.

In the midst of San Francisco’s years of explosive growth following the Civil War, James Bryce described California as having “more than any other [state] the character of a great country, capable of standing alone in the world.’’ He saw San Francisco as the “capital” of this country, “a commercial and intellectual centre and source of influence for the surrounding regions, more powerful over them than is any Eastern city over its neighborhood.”(1) Removed from other urban centers by half a continent or more, San Francisco’s politics—with few exceptions—differed in degree, not in kind, from the politics of New York or Chicago. Before exploring the major exception, the Workingmen’s Party of the late 1870s, some of the elemental structures of politics must be surveyed.

On any election day, in any American city in the late nineteenth century, similar scenes unfolded. Large crowds of men stood outside every polling place (politics was a distinctly male pastime) eagerly importuning voters to accept long, narrow pieces of paper called “tickets.” This ticket (in fact a ballot) carried the names of candidates for various offices. Until the adoption of the secret ballot (1891 in California), each political party provided ballots for the use of voters. The “party ticket” carried the names of that party’s candidates only. Voters wishing to cross party lines first accepted a party ticket, then scratched out the names of candidates they wished to avoid, and finally wrote in the names of their favorites. To make this easier, candidates sometimes distributed “pasters”—strips of paper with glue backing, imprinted with the candidate’s name and designed to be stuck over the name of his opponent. No secret booths existed for this activity. Instead, voters accepted a ticket from a party worker, then walked into the polling place and placed that ticket in the ballot box, all under the watchful eye of party retainers. Shrewd party leaders made scratching difficult or impossible by making tickets narrow, taking up all the space on them with either candidates' names or decoration, and sometimes using miniscule typeface to prevent the use of pasters.(2)

Political success, given such a system, required at the very least a corps of faithful party workers, enough to staff every polling place and distribute tickets, plus sufficient financial resources to print a supply of tickets. Campaigning usually became a matter of identifying ones supporters and mobilizing them on election day. Here, again, parties relied on a large corps of workers. The politics of mobilization implied as well the politics of organization. Organization began at the grassroots, with political clubs scattered throughout the neighborhoods of the city. Often located above or in back of a saloon, clubs included a range of social activities along with those of a political nature. All clubs affiliated with—and were sometimes created by—one of the major political parties. Sometimes clubs had geographic jurisdictions; others claimed ethnic or occupational constituencies. Still other organizations remained informal, based on a set of personal contacts at a place of work or recreation. Firehouses, militia companies, and neighborhood saloons all typically served as foci for political organizations.(3)

The county committee stood at the apex of this organizational structure in San Francisco, and it centralized decision making and directed party efforts throughout the city. In the nineteenth century, politics and parties were essentially synonymous. Balloting and mobilizing voters were but two of the many functions performed by parties. Nominations for office came from party conventions, held at the city level for city and county offices and within the various districts for members of the assembly, state senate, and House of Representatives. A “primary,” in which voters (or club members) chose delegates, preceded each convention. Access to elective office thus came entirely through the channels of party organization, from primaries through conventions to the printing of ballots and mobilizing of voters. Those who wished to break with the party organization usually did so by forming an independent party, complete with all the accoutrements of established parties. Candidates, if elected, usually remained attentive to the party leaders, who provided the necessary support for electoral success. Just as access to elective office came through the channels of the party, so too did parties typically guard the door to appointive positions. Appointive positions—patronage—provided much of the nourishment for the armies of campaign workers. Contracts and franchises—also forms of patronage— often flowed to those whose contributions helped to make success possible. Candidates themselves typically contributed 10 percent of their annual salary (or the annual salary of the position to which they aspired).(4)

Trials of a wavering citizen, 1870s.

One New York political leader of the late nineteenth century explained his personal prosperity by saying: “I seen my opportunities and I took ’em.” Ample opportunities existed for the political entrepreneur, as many as for the businessman of the day. Wealth and power awaited the shrewd and resourceful. The political system remained as unregulated as the economy and contained as many opportunities for manipulation. In a system based on maximizing voter turnout, the man who could provide voters commanded attention. Proprietors of sailors’ boardinghouses thus stood high in organizational councils, for each boardinghouse held as many as a hundred potential voters. No matter that most were usually away on a voyage—they often managed to vote anyway through careful planning by party leaders. On one occasion, it is alleged, even the crew of a foreign man-of-war tied up in the San Francisco harbor marched to the polls to take part in a city election. The system encouraged the appearance of “price clubs,” groups claiming to represent a particular constituency, which made endorsements from among the nominees of the regular parties and then offered, for a donation (a “price”) from each nominee, to print up tickets and distribute them to the constituency in question. Some such groups were undoubtedly legitimate, but others—like the Independent Democratic Liberal Republican Anti-Coolie Labor party—most likely sprang from the imaginations of small-scale entrepreneurs who assumed the candidates would pay the price requested rather than run the risk of alienating potential backers.(5)

Patterns of City Politics Before 1877

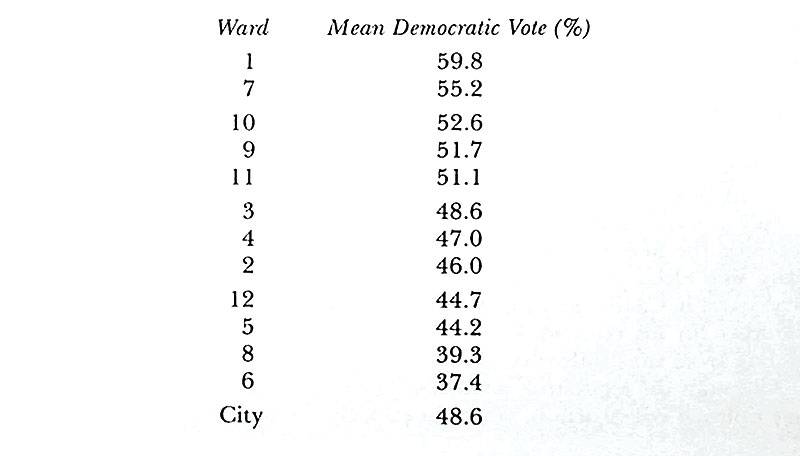

Throughout the late 1850s and 1860s, San Francisco politics was dominated by the heirs to the vigilantes, the People’s Party. Between 1856 and 1875, only one Democrat won the mayoralty. After the Civil War, however, memories of the events of 1856 receded ever further from mind. Thousands of newcomers poured into the city—many of them Irish and German immigrants—and the Democratic party began to emerge as the majority. Democrats won the mayoralty in 1875 and 1877, carried the city for their gubernatorial candidate in 1875, and usually could command a majority until the turn of the century. Arranging the city’s wards according to their mean Democratic vote between 1873 and 1877 (measured by voting for mayor, governor, and president) produces the following:

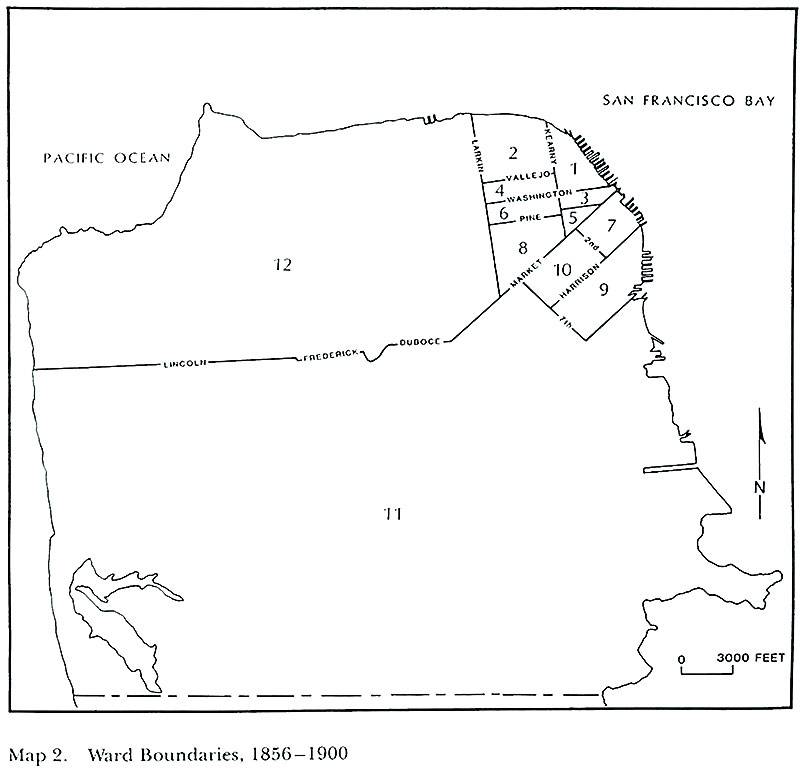

Map 2 identifies ward boundaries. As can be seen, the Democrats’ strength came from working-class sections of the city—the waterfront and South of Market, disproportionately of foreign stock (especially Irish) and Catholic. Democrats were weakest in the middle-class and upper-class areas north of Market Street, home to merchants, professionals, and others in white-collar occupations, also heavily of foreign stock but with a tendency to be German and Jewish rather than Irish and Catholic. The sixth ward, including Nob Hill, was the wealthiest area in the city and was least likely to vote Democratic. The second, third, and fourth wards were more heterogeneous, including a variety of occupations, ethnic groups, and lifestyles.(6)

In his description of California. James Bryce observed: “The most active minds are too much absorbed in great business enterprises to attend to politics.” Prominent San Franciscans, to be certain, found themselves “much absorbed in great business enterprises” throughout the three decades following the Civil War. Their interests ranged from the Comstock Lode to the wheat fields of the interior valleys, from Promontory Point to Los Angeles. from Alaskan fur and fish to Hawaiian sugar. The most prominent San Franciscans, those with mansions atop Nob Hill or on the peninsula, rarely involved themselves in city politics. They left the rough-and-tumble of club meetings, voter mobilization, and patronage distribution to others, characterized by Bryce as “the inferior men.”(7) But the lords of the Comstock and the masters of the Pacific railway did not, by any means, absent themselves from politics. On the contrary, they involved themselves thoroughly and sought constantly to involve the government as an active partner in their enterprises. They paid little attention to city government, relatively powerless because of the Consolidation Act, but turned instead to those governments with real power, those in Washington and Sacramento and— occasionally—Carson City and Honolulu.

Notes

1. Bryce, American Commonwealth, 2:425, 428, 430-431; Christopher A. Buckley, “The Reminiscences of Christopher A. Buckley,” Bulletin, Jan. 24, 1919, p. 13.

2. Bryce, American Commonwealth, 2:143; William A. Bullough, The Blind Boss and His City: Christopher Augustine Buckley and Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (Berkeley, 1979), pp. 58-60; Erik Falk Petersen, “The Struggle for the Australian Ballot in California,” California Historical Quarterly 51 (Fall 1972): 227—243.

3. Bullough, Blind Boss, pp. 58-59, 77, 89-91, 154, 195-197; Neil Larry Shumsky, “Tar Flat and Nob Hill: A Social History of Industrial San Francisco During the 1870s,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1972, ch. 6; Jon M. Kingsdale, “The ‘Poor Man’s Club’: Social Functions of the Urban Working-Class Saloon,” American Quarterly 25 (Oct. 1973):472 — 489.

4. Bullough, Blind Boss, pp. 58 — 60, 87—89; Bancroft, History of California, 7:315 — 317; Bryce, American Commonwealth, 2:85 — 89; Walton Bean, Boss Ruef’s San Francisco: The Story of the Union Labor Party, Big Business, and the Graft Prosecution (Berkeley, 1952), pp. 2 — 4.

5. George W. Plunkitt, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, ed. William L. Riordon (New York, 1948), p. 4; Bullough, Blind Boss, pp. 58 — 60; Henry George, “The Kearney Agitation in California,” Popular Science Monthly 17 (Aug. 1880):438-439; Petersen, “Struggle for the Australian Ballot,” pp. 228—229. Bullough and Petersen both use “piece club”; George used “price club.”

6. San Francisco, Board of Supervisors, Municipal Reports (1872 — 1873), pp. 558-559; ibid. (1874-1875), pp. 768-775; ibid. (1875-1876), pp. 750-751; ibid. (1876-1877), pp. 1042-1043; ibid. (1878-1879), pp. 523-526, 758-807.

7. Bryce, American Commonwealth, 2:425.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 6 “Politics in the Expanding City, 1865-1893”