Downtown Scenes Early 20th Century

Historical Essay

by William Issel and Robert Cherny

Mission Street at 1st, c. 1910.

Photo: C.R. collection

Bounded on the west by the Western Addition, on the south by South of Market, on the north by Nob Hill, Chinatown, and North Beach, and on the east by the bay is Downtown, an area that included the warehouse-wholesale district along the waterfront, the Financial District along Sansome and Montgomery between California and Market, a shopping district adjoining the Financial District on the west, a hotel district west and south of the shopping district, and a high-density residential district overlapping and west of the hotel district and, more generally, throughout Downtown. A vice district, the Barbary Coast, stretched along Pacific Street for a half-dozen blocks inland from the waterfront. Helen Hunt Jackson recorded her initial impression of Downtown:

When I first stepped out of the door of the Occidental Hotel, on Montgomery Street, I looked up and down in disappointment.

“Is this all?” I exclaimed. “It is New York—a little lower of story, narrower of street, and stiller, perhaps. Have I crossed the continent only to land in Lower Broadway on a dull day?”

Jackson soon discovered that there was more to San Francisco than a New York with smaller buildings and narrower streets, but her initial impression underlines the fact that Downtown in San Francisco was, in many ways, not greatly different from the downtown area of any of the dozen or so major cities of the day. The typology of urban development outlined by David Ward fits the San Francisco case as well as it does Boston.(46)

First Street looking south from Market, c. 1928.

Photo: SFDPW, courtesy C.R. collection

The area nearest the waterfront had characteristics similar to its counterpart South of Market—high population density, more than two-thirds male, half foreign-born, and only half of the population living in families. Further inland, between Mason and Van Ness, the population was quite different from that along the waterfront. Only three-quarters lived in a family (compared with 84 percent citywide and more than 95 percent in the Mission or Western Addition), but the population was almost evenly divided between men and women. The population density was the highest outside South of Market and Chinatown, not surprising for an apartment-house district. This area of the city had the highest proportion of people with both parents born in the United States; Germans took first place among foreign-stock groups. Many of these people were employed in the central business district as clerks, salespeople, professionals just beginning their practices, or business people who chose to live near their work. Hotel living was an old tradition in the city, one still followed by many in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including such prominent people as James Fair, who lived at his Lick House. Samuel Williams, in 1875, defined some social essentials:

Living at a first-class hotel is a strong presumption of social availability, but living in a boarding-house, excepting two or three which society had indorsed as fashionable, is to incur grave suspicions that you are a mere nobody. But even in a boarding-house the lines may be drawn between those who have a single room and those who have a suite.(47)

Sansome and Market streetcar crash, c. 1929.

Photo: C.R. collection

Southeast view across Market from Battery, looking down First Street, November 10, 1936.

Photo: SFDPW, courtesy C.R. collection

New Montgomery south from Market Street, November 10, 1936.

Photo: C.R. collection

Geary Blvd. looking west at Grant, Union Square and St. Francis Hotel visible in distance, c. 1929.

Photo: San Francisco History Center, SF Public Library, courtesy C.R. collection

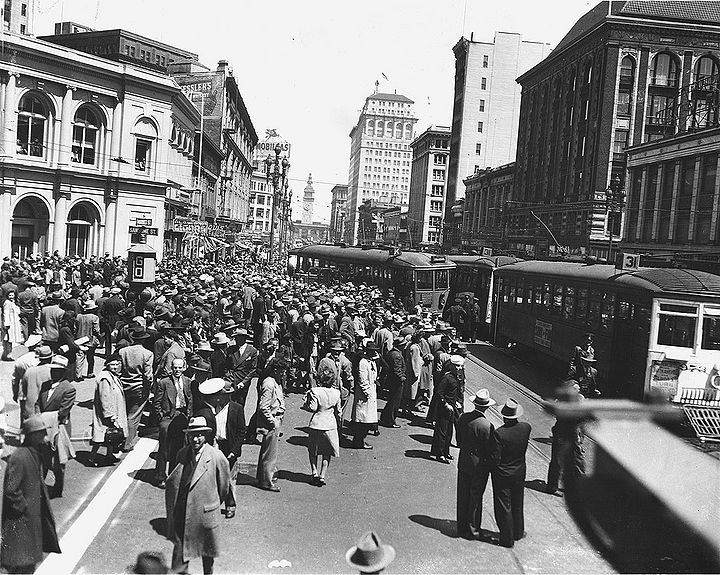

Streetcar Number 6 has gone off the rails on Market near Powell, c. 1940.

Photo: C.R. collection

Notes

46. James E. Vance, Jr., Geography and Urban Evolution in the San Francisco Bay Area (Berkeley, 1964), pp. 18–24; Herbert Asbury, The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld (Garden City, N.Y., 1933); Helen Hunt Jackson, quoted in Lewis, This Was San Francisco, pp. 175–176; David Ward, Cities and Immigrants (New York, 1971), pp. 87–102.

47. Table 104, “Population, Dwellings, and Families, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” Twelfth Census of the United States: 1900, vol. 2, pt. 2, ?. 640; Table 23, “Population by Sex, General Nativity, and Color, for Places Having 2,500 Inhabitants or More: 1900,” ibid., p. 610; Table 5, “Composition and Characteristics of the Population for Wards (or Assembly Districts) of Cities of 50,000 or More,” Thirteenth Census of the United States: Abstract of the Census with Supplement for California, p. 616. The relevant assembly districts for Downtown in 1900 were the 39th, 42nd, 43rd, and 45th. The 45th was nearest the waterfront and included part of North Beach. The 43rd included Chinatown. The 42nd and 39th are best for summarizing the characteristics of other parts of downtown, although the 39th included many residential areas not unlike parts of the Western Addition. For 1910, the relevant districts are the 42nd through the 44th. The 44th was nearest the waterfront and included Chinatown. The 42nd and 43rd were between Mason and Van Ness and Market and Broadway, the heart of the apartment district to the west of the central business district. Williams, “City of the Golden Gate,” p. 280; see also his comments on boardinghouse living (p. 277). Twenty of the “prominent hotels” are listed with their permanent guests in Hoag, ed., Our Society Blue Book: 1902.

Excerpted from San Francisco 1865-1932, Chapter 3 “Life and Work”